UCU and the University Worker: Experiments with a bulletin

by

The University Worker

April 28, 2023

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

Attempts at workplace intervention in the higher education

inquiry

UCU and the University Worker: Experiments with a bulletin

by

The University Worker

/

April 28, 2023

in

In and Against the Union

(#17)

Attempts at workplace intervention in the higher education

The autumn term of 2022 saw another round of industrial action called in the higher education sector in Britain. This is part of a dispute that has, on and off, been going on since UCU was founded in 2006. Notes from Below has published a rank-and-file bulletin in various forms since 2018, although some of the editors have been involved in disputes going back over a decade. We’ve experimented with different approaches to a rank-and-file bulletin during each round of industrial action.

For this current issue of Notes from Below, we have collectively written this piece reflecting on the practice and process of bulletin writing. Bulletins are regular publications written by workers for the purpose of organising. These can take many forms with content as appropriate to the workplace The University Worker has mainly been produced as a two-page pdf that can be printed out and distributed on picket lines.1

At Notes from Below, we set out to make and host bulletins as a key part of the publication. We think that bulletins provide an important way to connect our ideas to existing struggles and intervene within them. The University Worker is now the longest running bulletin on the website, although we have also hosted bulletins from English Language Teachers, Deliveroo workers, other precarious workers, and some one-off leaflets.

The University Worker has tried to do two things. First, share experiences of local picket lines across larger national disputes. This has involved calls for reports from different universities and then republishing these in subsequent issues. In this way, the bulletin has enabled members to reflect on and write about their experience of being on strike for members across the country. Second, putting forward arguments about the direction of the dispute. Both of these come from a lack of a forum for these activities in the national union. They are also part of an ongoing attempt to build a space for rank-and-file organising in and across branches.

The 2018 Dispute

In 2018, a round of strikes was called by UCU. This included 61 universities involved in the USS pension scheme. The union called a series of strike days, escalating in length over four weeks. It started with two days from February 22-23rd, then February 26-28th, March 5-8th, and March 12-16th.

On the 21st of February we launched the first issue of the University Worker. This was less than a month after the launch of Notes from Below on the 29th of January. It was written by a section of the editorial collective who were working in universities. The bulletin focused on explaining what it was for and ideas for the dispute, including learning from outsourced workers, student support, and publicising a demo.

As part of the promotion, we launched a Facebook group for distributing the bulletin that quickly moved beyond our own networks. At its peak it had 1,500 members and featured rank-and-file discussions. We also published a piece in the first issue of Notes from Below arguing for Six points on the eve of the UCU strike.2

In the second week, we published reports from ten university picket lines, as well as an editorial about the strikes so far. The main aim was to circulate news of the strikes, something the national union has little interest in. On the 28th, UCU called a national demonstration with at least five thousand people marching through the snow. The union also entered into negotiation with UUK, the advocacy organisation for university vice-chancellors. For the third week, we published reports on the demonstration, international solidarity, and an editorial on the rank-and-file approach to negotiations.

By the fourth week, we decided that a daily issue was needed as things started shifting quickly in the dispute. It was also the first week that we were on strike for the full five days. There were lively discussions on the picket lines, frequently about strategy beyond the individual university. The picket lines had also been bolstered with early career members, particularly following the decision to introduce free student-teacher membership.

On day one of the fourth week, we argued for more strike days as we approached the Easter holidays, as well as a model motion and international reports. UCU then made a deal with UUK during ACAS negotiations, agreeing to keep the defined benefit scheme, so long as more was paid into it, while looking into other options. There was also a demand that UCU members would go back to work and teach missed classes without being paid. In response, we published a special “It’s a sell out” issue. The bulletin called for three things: first, emergency meetings on picket lines with wildcat action if needed. Second, a demonstration at UCU headquarters. Third, to sign an open letter rejecting the deal. It also had, arguably, the best meme of the University Worker.

The open letter started by the University Worker received 10,000 signatures and there was an angry demo - including a brief occupation - outside of the union offices that piled pressure on the union. On March 14th, we published a special “We Beat the Deal” issue. It reported that at least 50 out of the 64 branches had rejected the deal and the union was forced to withdraw it.

The Easter break halted the momentum of the strike and the dispute tailed off. Another deal appeared from UUK, proposing a so-called “Joint Expert Panel.” On the 5th of April, we published a fifth issue denouncing the deal and calling for a rejection and no vote. The union membership voted to accept the deal - although 36% rejected it. The IWGB continued strike action of outsourced workers at Senate House and we called for solidarity and support.

The dispute effectively ended with UCU and UUK agreeing to investigate the pension scheme, albeit with an expert panel split between the two. It would later become clear that the vote-deciding chair was far from independent, consistently voting with UUK. There was a brief further moment of industrial action as UCU staff members walked out of the national congress in support of the general secretary Sally Hunt.3

We reflected on the 20184 dispute in detail and the process of how the bulletin was made and used in a podcast.5

The 2019-20 Dispute

On the 31st of May 2019 we relaunched the bulletin after the election of Jo Grady as general secretary of the UCU. As Sai Englert wrote at the time:

“The recent election of Jo Grady as General Secretary of the UCU represents a watershed moment in the history of the union, and it is difficult to overstate its importance. Indeed, the union has only known one General Secretary in its decade and a half of existence – Sally Hunt. It has been run throughout this entire period by an alliance between Hunt loyalists and the ill-named Independent Broad Left. This control has been so powerful, that many assumed that the recent election would simply be an exercise in crowning Mark Waddup – Hunt’s heir apparent.”6

The next wave of action started in November of 2019 over two issues. UCU congress voted in favour of launching the “four fights” campaign, linking pay to equality, casualisation, and workload. First, there were ballots across higher education unions over pay, and second over pensions as UUK returned for another attack. UCU organised disaggregated ballots on a per-university basis. On pay, 54 branches out of 148 reached the 50% turnout threshold, while on pensions, only 43 out of 64 branches. UCU organised eight days of strikes and we published an issue on the first day and then second day of the first week. The “Joint Expert Panel” reported back, recommending further talks and changes to the pension scheme.

There was a period of reballoting in which 14 more universities were balloted. A few more universities reached the threshold, increasing the number of branches taking action (with a mixture of pay and conditions and/or USS) to 74. UCU called forteen days of strike action, over 20-21st of February, 24-26th of February, 2-5th of March, and 9-13th of March. We brought back the University Worker twice in each week: in week one with reports, week two with reports, week three with a special issue on a potential sell out, and the final week with reports.

There was then a gap with no more action called due to the Covid-19 pandemic. UCU issued a statement to members and we published an anonymous response. We then supported an open meeting, titled If you don’t do it, we will, bringing together anti-casualisation activists and union members. There was then a long pause in industrial action.

The 2022 Dispute

We started the 2022 dispute with an expanded editorial board, including more members who worked in higher education. As we knew the details of the strike days well in advance, we had time to plan for the latest issue of the bulletin. We made a deliberate decision to expand the group involved in the production of the bulletin. First, this meant starting a WhatsApp group to coordinate the process, inviting people who had participated in the previous issues to take part. Second, we started a WhatsApp announcement group for sharing the bulletin and putting out calls for reports and contributions. Given there were 150 universities taking part in the strikes, this was an attempt to build a network beyond our own existing contacts - and particularly wider than London.

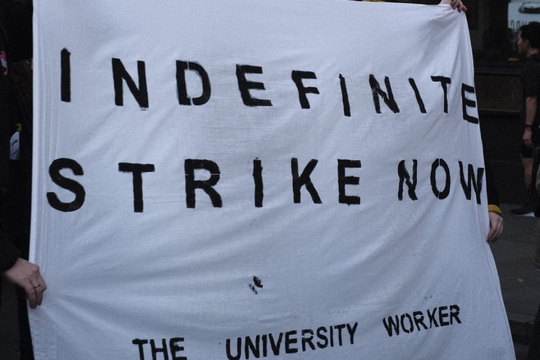

For the first strike day, we published a bulletin on the 1st of October that included a call for contributions from picket lines, as well as reports from the wildcat strike at Amazon and the postal worker strikes.7 We then prepared an editorial with a submission form, followed by bulletins for each of the days of the strike, on the 24th of November, 25th of November, a second short editorial, and an open meeting for rank-and-file UCU members on the 28th of November. The main theme that ran through the bulletin was the need to escalate action and calls for an indefinite strike. In the second week of the dispute, we published another bulletin. This specifically called for indefinite strike action and had a petition alongside it. As in-fighting between factions inside the union bureaucracy intensified, we highlighted the difference between communications for the UCU negotiators and the General Secretary.

During the break in the dispute over the winter holidays, we decided to try and keep the discussion going by inviting contributions on strategy that were published online. The first was a collectively written piece on How to Build Indefinite Strikes. The aim was to show that indefinite strikes were not just a slogan for a banner (although we had also made a banner), but were a tactic that we could use to win the dispute. The second was a piece on How to Stop a University by two members of the UCU committee at Queen Mary in London.8 We commissioned this piece because they both had experience of organising a marking boycott in the previous year. While we had heard about this experience, this was because we had existing contacts with the branch. Publishing the piece was an attempt to get this shared more widely. We then - despite having no connection to the political group that wrote it - republished another contribution to the debate, asking What the Hell is Going On?9 This was followed by an account of the Marking and Assessment Boycott at Goldsmiths.10

As this article goes to press, changes are continuing to unfold in the UCU dispute in 2023. The strikes were paused, brought back again, and demonstrations were called outside of the UCU headquarters. We are currently fighting to escalate the dispute and continuing to publish The University Worker. It is always difficult to fully reflect on a live struggle, particularly while continuing to try and intervene within it. We intend to return to this reflection later and draw out lessons for the struggles ahead in higher education.

Reflection on the University Worker

The University Worker has gone through a series of phases since we first launched it in 2018. As a strike bulletin, it has been a response to the extended disputes in higher education that have effectively been ongoing since the union was formed in 2006. As a small group within a much larger national union, we wanted to apply our politics to a strike we were involved in. Looking back on the disputes we have sought to influence since 2018, a few points stand out.

First, the strikes we’ve fought have mostly remained narrowly concerned with the terms and conditions of employment for UCU members. Our version of class composition theory says that when workers engage in a struggle in their workplace, that struggle sometimes “leaps” into the terrain of politics.11 When this process occurs, the sectional interests of a particular group of workers fighting a particular boss over particular issues becomes secondary to the general interests of workers at large, and their fight against a society and an economic system controlled by their bosses. In an agitational model of Marxist struggle12, the major role of militants is to intervene wherever possible to initiate and/or support this transition from economic to political struggle.

In the context of the UCU, that transition would mean a continuation of the demands for “free education” that dominated the student movement between 2008-2017. This movement was defined by an opposition to tuition fees - but also opposition to institutional complicity with the Israeli oppression of Palestine, to the narrowing of university education into a form of job training, to police intervention against protests on campus, and to the outsourced exploitation of support staff. Like many other UCU members, we were there, fighting for those demands on the ground as students. With the added insight gained from working in universities for a decade since, our cohort would now likely also stress the importance of self-management and the need for dramatic changes in the funding model and social purpose of universities as institutions. But when you look at the official communications about this dispute produced at both branch and national union levels, you don’t see these demands. Instead, the issues up for debate have been narrowed right down. Theoretically, we are fighting issues with pay, pensions, workloads, precarity, and discrimination - but very few members expect the union to achieve a negotiated agreement that covers anything more than pay.

The idea of the university as a public institution that produces social use values has fallen away into pure economism through these disputes. Many rank-and-file activists are motivated to strike by the desire to oppose the managed decline of universities as institutions, but you’d be hard pressed to work that out from union communications. This political imaginary of a liberated, free education system has rarely got much airtime beyond group discussions on picket lines, or rhetorical flourishes at the end of a speech. In this regard, we’ve failed to have the impact we would have hoped. The bulletin has been hard-pressed to support effective trade unionism, with every dispute we’ve intervened in ending in defeat, let alone making the transition to a wider struggle over the shape of universities as institutions. However, rank-and-file activists remain highly-motivated by a vision of a different form of higher education. What else could explain the consistent organising efforts that have built successful ballot after successful ballot in the face of an ongoing employer offensive despite a frankly incredible record of defeat? Our hope is, as this current strike continues, that we can increasingly find the space to combine discussions on how we win this dispute with what we want to win.

Despite our support for building coordination across university union branches representing different segments of the workforce, there are still only localised examples of industrial unionism developing from below. This is mostly still focused around UCL, with strikes sometimes being coordinated between UCU and outsourced workers in IWGB. And even in this localised example, trade union territorialism prevents the local UNISON branch from joining and making this coordination tripartite. However, the organisation of unions in higher education remains a barrier to coordinated action, particularly with the failure of some unions to ballot or reach the ballot threshold. This is a much longer-term issue in the labour movement in Britain.

It is also worth noting that the elected positions in UCU have historically been divided between two factions: UCU Left and IBL. After the election of Jo Grady, a third faction, UCU Commons, emerged. The union has long been divided by factional conflict, mainly at the NEC and other national bodies, while only sometimes featuring at local branches. Between us, we think we have been part of at least four different attempts at rank-and-file groupings - all of which have either fallen away after the strikes or broken apart due to infighting. Instead of trying to launch rank-and-file networks in the absence of a militant and organised rank-and-file, we have instead focused on the University Worker.

Our aim has been to try and move beyond the factional divisions that are mostly present in the official structures of the union - rather than being something you encounter in departments or on picket lines. Instead of aiming to replace bad bureaucrats with good ones - something that does not have a record of success in UCU - we have tried to connect people on strike and facilitate a collective discussion. We also hope that the University Worker shows that bulletins are a worthwhile tool in industrial struggles. They do not require a lot of resources and can be started by a small group of rank-and-file workers. We are not arguing that we are a decisive force in how the strikes have played out in higher education, but we have been able to put out arguments at important points. These interventions represent the collective of workers that write the bulletin, rather than a union faction tied up within the bureaucracy.

Making your own bulletin

One of the aims of writing this piece was to show that doing something like this doesn’t take a lot of resources or experience. Once you have a document template for one bulletin, creating others is mostly just a process of copying-and-pasting your articles into it. Some of our most effective bulletins were written the night before a strike, either on a phone call with a google doc open, or gathered round a laptop or phone in person (sometimes in a pub). A bulletin is about rank-and-file workers taking initiative during a dispute. We don’t have to just sit around waiting for the union to communicate what is happening or tell us what to do. We can test out ideas with a bulletin and then discuss them on picket lines. We might get things wrong, but the point is to encourage a conversation and debate between workers. This is about trying to organise strikes from below.

The main thing that has strengthened the University Worker has been building a network who want to read and contribute to it. We have access to printers and could run off hundreds of copies, but otherwise we could have distributed the pdf too. We have supported other bulletins in the past and as we say on our website: If you have a bulletin that you’re writing (or want to write) with co-workers or want to get involved with the distribution network for any of the bulletins below, contact us at Notes from Below. We can provide support with templates, editing, as well as printing physical copies where possible.

-

Past issues and articles by The University Worker can be viewed here. In order to avoid inundating the reader with footnotes, we have only cited in this article those named bulletins and articles that were not published under the The University Worker name ↩

-

Woodcock, Jamie. ‘Six points on the eve of the UCU strike’. Notes from Below. 21 Feb 2018. ↩

-

Englert, Sai. ‘Report from UCU Congress 2018’. Notes from Below. 1 Jun 2018. ↩

-

Englert, Sai and Woodcock, Jamie. ‘Looking Back in Anger: the UCU strikes’. Notes from Below. 30 Aug 2018. ↩

-

Available to listen here. ↩

-

Englert, Sai. ‘After Grady’s election - where is the rank and file?’. Notes from Below. 31 May 2019. ↩

-

Notes from Below. ‘Oct 1st Bulletin - Submit a Strike Report!’. Notes from Below. 30 Sep 2022. ↩

-

Dinnen, Zara, and Eastwood, James. ‘How to Stop a University’. Notes from Below. 18 Dec 2022. ↩

-

Socialist Alternative members in UCU. ‘What the hell is going on?’. Notes from Below. 18 Dec 2022. ↩

-

Newman, Joe and Mozzachiodi, Roberto. Notes on a Marking and Assessment Boycott. Notes from Below. 20 Jan 2023. ↩

-

Notes from Below. The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition. Notes from Below. 29 Jan 2018. ↩

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

author

The University Worker

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Welcome to the future: this strike wave is just the start

by

Notes from Below

/

April 28, 2023