Welcome to the future: this strike wave is just the start

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

April 28, 2023

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

Introduction to issue 17, In and Against the Union

inquiry

Welcome to the future: this strike wave is just the start

by

Notes from Below

/

April 28, 2023

in

In and Against the Union

(#17)

Introduction to issue 17, In and Against the Union

Summary

Since 2008, things have been getting worse and worse for working people - but there haven’t been many strikes. On the other hand, since mid-2022 the number of strike days has risen to a level not seen since 1989. This strike action, although impressive, has its flaws. It was kicked off by union general secretaries, not by rank-and-file workers. The tactics used in the disputes have been very soft and have not maximised our power. The political demands raised by the disputes have been significant (mostly around public funding) but they’ve not been linked to a wider movement. It seems quite possible that we could lose a lot of the ongoing strikes, as the government and the employers are determined not to give in. But there is also a big opportunity. Right now, we can rebuild rank-and-file rep networks. These networks can take control of these strikes and start to fix those problems. This strike wave is a preview of what the class struggle is going to look like in the next decade. We are going to have to fight over and over again to stop real terms wage cuts. But now we know that this is the pattern we’re likely to face, we can organise and prepare for it.

Amidst the gloom

Britain is a society in decay. Since 2008, a gradual process of post-Imperial decline has accelerated into something more dramatic. The economy is now defined by the stagnation of real wages, the intensification of work, the undermining of employment protections , the massive expansion of precarity, and the further consolidation of a pattern of low wage, low productivity work in the service sector.

Society more broadly has also taken a beating. Austerity plunged millions into poverty, kicked off the managed decline of public services and the cannibalisation of social infrastructure. More and more people are facing declining living standards, including those who previously thought they were secure. The state has taken on an increasingly authoritarian form, evidenced by a gradual increase in the repression of strikes and protests. This began with the aggressive policing of the student and anti-austerity movements and has since escalated through a raft of new anti-strike and protest laws, and the relentless persecution of desperate migrants.

Every area of our daily life bears the marks of a brutal 15-year long ruling class attack, which is itself built on the neoliberal assault that smashed the post-war settlement. Surveying the damage from our current perspective, you’re left with the impression that we live in a managed democracy that is teetering on top of its increasingly rotten foundations.

But amidst the gloom, something is happening. In the face of rising inflation and the threat of widespread real wage cuts, hundreds of thousands of workers have taken strike action. Strike numbers, which have stagnated for decades, have risen to levels not seen since the winter of 1989/90. This issue presents the view of workers who have found themselves on the front line of this new strike wave.

In Class Struggle and Recomposition at the Royal Mail, a striking postal worker reflects on their current national dispute, the degradation of social bonds in the workplace, and the necessity of rebuilding a confident shop floor militancy.

In Striking as a Nurse: Story from a first-time striker, a nurse recounts their experiences with the current strike action, and how it has fitted into their wider journey of politicisation.

In The NEU strike - winning a rank-and-file led union, teacher and NEU rep Vik Chechi-Ribeiro discusses the background to the ongoing national strike action in schools, and where opportunities lie in using this dispute to rebuild a rank-and-file in the education sector.

In Struggles on the Railways we hear from a worker in specialist manufacturing for trains, drawing out the dynamics of that industry and how they have come to shape the current state of union and rank-and-file struggles.

In The University Strikes, as seen from Birkbeck Library, a UNISON member at Birkbeck walks us through their current local and national disputes, and where they can escalate from here as an industrial workforce.

In UCU and the University Worker: Experiments with a bulletin, a group of workers associated with the ‘University Worker’ bulletin reflect on the disputes in the sector since 2018, and how their experience of producing a strike bulletin has allowed them to contribute to building an independent rank-and-file within the union.

Taken together, these contributions map out some of the key contours of the ongoing disputes, and present how workers - ranging from veteran union activists to first-time strikers - have understood their experiences on the picket line. In the rest of this editorial we will zoom out to consider three further questions: how much strike action there has been, what form it has taken, and what the implications are for our wider analysis.

How much strike action?

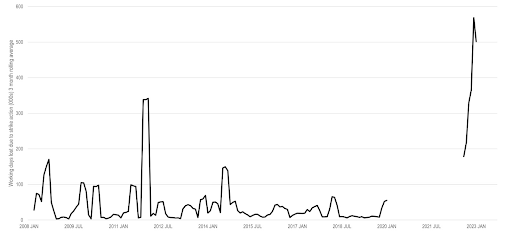

From our vantage point today, it is easy to forget just how profound the recent decline in strike action has been. Between 2008 and the present the total number of people employed in the UK has varied between 29 and 33 million. In eight separate months during this period, the Office for National Statistics has recorded less than 2,000 working days lost to strike action across the entire country (there would almost certainly be more, but they halted data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic.) This level of strike action is almost extremely low. To put that in context, assuming an average for the period of 22 working days a month and roughly 31 million people in employment, there are 682,000,000 total days worked per month. 2,000 days lost to strike action is equivalent to just 0.00029% of the total days worked. This decline into negligible levels of action continued a long historical trend, which saw the levels of action taken by workers in absolute terms plunge off a cliff, even as the size of the overall workforce grew.

The post-2008 era did see some high points. There were nearly a million days lost in November of 2011 during the public sector pension strikes. But that was a one-day demonstration strike that had little to no sustained impact. By and large, the combination of austerity and the worst decade for real terms wage growth since the dawn of the 19th century was met with no organised resistance from the trade union movement.

This history is essential context for the recent explosion. The numbers of days lost in 2022 are impressive: 357,000 in August, 422,000 in October, 461,000 in November, and 843,000 in December. What is most remarkable about this increase, however, is its sustained nature. This is not just a one-month high, but a consistently increased level of action over many months. This becomes clearer if we look at a three month rolling average of days lost:

The three months up to December 2022 is the first time the rolling average of days lost to strike action has been over half a million since the winter of 1989/90, when Margret Thatcher was approaching the end of her time as prime minister and the anti-poll tax movement was at its height. We’re not just seeing one-off action, but sustained, widespread, and coordinated action.

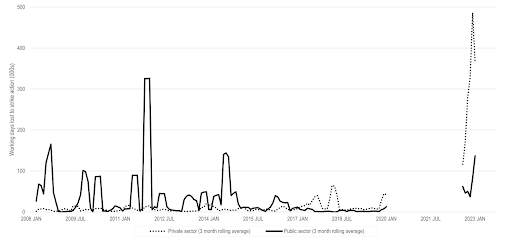

In addition, we’re seeing a real change in the split between private and public sector strike action. Whereas most of the low levels of strike action taken in the post-2008 period have been concentrated in the public sector, private sector strikes are increasingly contributing the bulk of the days lost.

This trend has doubtless been driven by the very significant action taken by the CWU in the now-private postal service and by RMT and ASLEF against private rail operators. There might be other contributors too, but the ONS have stopped collecting the data that details how this action is broken down by industry. For the moment then, we will have to leave the distribution of this action across the private sector as an open question.

What kind of strike action?

Across all the articles collected in this issue, a few common themes come to the fore again and again. First, the absence of rank-and-file control of the disputes. Second, the restrained tactics deployed by workers - often in the face of extremely aggressive management provocation and victimisation. Third, the existence of soft political demands about the funding of public services and the support of both these demands and the workers making them amongst the wider population. Fourth, the lack of a political movement to express the motivations behind the strike on the level of bourgeois politics or through social movements. Fifth and finally, the difficult balance of forces facing striking workers in all industries. By linking up lots of different instances of inquiry, we can start to paint a general picture of what kind of strikes have made up this bigger wave. As with all worker writing, we get a sense of struggle on the ground. These are not filtered through either a hostile media or smoothed out through trade union communications, and so include the real tensions and possibilities contained in this wave of strikes.

The absence of rank-and-file control

In almost every major case, these disputes were initiated by union leaderships. Far from being provoked by rank-and-file demands, these strikes have been kicked off by General Secretaries. They are seeking to get out ahead of rising militancy and demonstrate their ability to win pay rises in the face of significant inflation. Whilst we shouldn’t condemn union leaders for taking the initiative, it is vital to understand that rather than launching strikes because ‘that’s what unions do’ they are in fact advancing their specific interests as a group (interests which are distinct from those of workers). If strikes no longer serve their purposes then they will be just as quick to stop launching ballots unless there is increased rank-and-file pressure.

This is why the particular lack of rank-and-file organisation evident in these disputes should be such a source of concern. Networks of union reps exist across many of the major workforces, but none have yet been able to set the direction or demands of their strikes. The cycles of trade union militancy that emerged in the 1910s and 1970s were both accompanied by the growth of shop stewards movements built on workplace committees. These brought together all the reps on a work site (regardless of whether they belonged to different unions). They were complimented by wider ‘combines’ which connected workers in the same company, city, industry, or union. These independent bodies were able to place their union leaderships under immense pressure, trying to steer disputes from the bottom-up. They also played a vital role in circulating insights about how to organise and fight in the specific circumstances they faced on the ground. The lack of such institutions is a significant limit on both the effectiveness of these current strikes as a negotiating tactic, as well as their ability to contribute to a working class political movement aiming for revolutionary change.

As can be seen from The University Worker article in the issue, the behaviour of the UCU leadership has only been possible because of a weak rank-and-file. While the Higher Education Committee initially called for indefinite strike action, the leadership has been able to ignore that and call much more limited action. A combination of a communications-led strategy with a ‘charismatic leader’ and mass email polls has been used to undermine activists on the ground just weeks before the action was set to start. Midway through the strike, the union leadership deposed the elected negotiators and suspended strike action for two weeks after failing to secure any kind of concrete deal. Again they bypassed union representative structures and then used a rigged email vote to try and secure retrospective backing for an undemocratic stitch up. The employer’s response was to declare wage negotiations concluded and impose a far below inflation pay offer already rejected by members. The union has been left demobilised in the middle of a reballot, with no ability to reinstate the cancelled strike days due to the government’s repressive trade union laws. None of this would have happened if rep networks were able to dictate terms to the leadership.

In this context, our role as militants seems clear: we need to build the rank-and-file. We can do this in three ways. First, by trying to connect reps within and between workplaces. Second, through identifying how to expand those networks by developing reps over time. Third, by spreading knowledge about how to organise and fight and engaging with other reps to discuss and refine our political ideas and strategies.

Restrained tactics in the face of management aggression

A French ultraleft militant once talked to one of us about his youthful memories of England. He said that he used to come over on the ferry with his comrades and drive straight to the nearest big strike. There they would offer their assistance to the shop stewards, and more often than not they’d be given a useful task to carry out in the dead of night. “Ah,” he reminisced, “the English really knew what a picket line meant. Is it still like that?” He was disappointed with the answer.

Today, it is not uncommon for picket lines to be reduced to a small cluster of six people with official hi-vis vests. Strikebreakers are allowed to cross without interruption, and the tone is quiet, friendly, personable - perhaps even wary of causing an inconvenience. Too often these are seen as demonstrations, rather than disruptive activities. Strikers are standing there to show what they believe, not to bring their workplace to a grinding halt.

This decline in rank-and-file power is perhaps not surprising given the context of low trade union strike levels and state repression - but is still a major problem. Pickets should be actively dedicated to shutting down the workplace (as Vik Chechi-Ribero argues in his article, “picket lines should be actually picketing”), leverage tactics (developed to a high level by Unite1) should be deployed wherever possible, and outside groups should be engaging in supportive direct action. None of this has been widespread enough to make us confident that the strike action being taken by so many is being used to maximum effect. In part, it feels like the British trade union movement has become excessively polite. Perhaps because of the threats posed by the most rabid far right press in Europe and a hard right government that wouldn’t blink at seizing union coffers, many of these strikes seem to be tactically meek.

Our bosses have no need for politeness. The Royal Mail have relentlessly attacked the CWU in the media, and taken their long-running campaign of rep victimisation to new heights, with at least 200 suspended. As a postal worker explains in Class Struggle and Recomposition at the Royal Mail , this is a conscious attempt to undermine the workforce’s morale and destabilise them in anticipation of strike action. Universities have also ramped up their wage deductions, with some threatening to take 100% of wages every day until missed strike teaching had been made up. Doubtless there are more examples from other sectors that demonstrate just how seriously the bosses are taking this fight.

On the workers’ side, there have been limited examples of stronger tactics for us to point to. The Royal Mail strike has seen some scab agency vans being blocked on strike days, but this has been almost exclusively by supporters rather than striking workers themselves. It is also far from a generalised form of action. The joint NEU/PCS/UCU/Equity demonstration in London in February was loud and vibrant, but was in the end just an A-to-B demonstration. If we want to win, we will have to escalate our tactics.

Soft political demands and popular support

When public sector workers (who are ultimately employed by the state) go on strike, their demands cross over into politics almost by accident. Demands about working conditions in schools and hospitals can easily become debates on education and healthcare funding. For example, NEU and RCN demonstrations have both been characterised by placards carrying slogans demanding not just wage increases but funding increases to the system as a whole. These demands start in the workplace. After all, it would be less stressful and alienating to work in a properly-funded system. However, they also have profound implications for those outside the workplace who rely on these services as pupils, patients, parents, and carers. It is worth remembering that these are not radical demands. They are about returning to the welfare state of the past, about regaining something we’ve lost rather than fighting for a new kind of society.

Public sector strikes have a surprising level of public sympathy. Part of this might be a legacy of the ‘key worker’ idea which became so popular through the pandemic. The latest polling shows broad support for striking workers: 57% support the nurses (vs. 31% against), 52% support ambulance workers(vs. 35% against), 40% support primary school teachers (vs. 43% against) and 38% support railway workers (vs. 46% against). After months of action, this level of support is remarkable. However, that level of support has not turned into a social movement to actively back the strikes.

Lack of political expression and social movement support

Unsurprisingly, there is little political support for striking workers from the Labour Party under Keir Starmer’s leadership. From 2020 onwards the party has moved hard to the right and purged both Corbyn and many of the members associated with his leadership. The very soft demands to properly fund schools and hospitals go unsupported even by the opposition. The demands of these strikes have no major supporters in the Houses of Parliament. But there is not a strong social movement behind them, either.

Enough is Enough - a movement initiated from above by the union leaderships of RMT, CWU, ACORN, the Tribune magazine and some Labour left MPs - launched as an attempt to fill the void. It began with a series of rallies around the country in which audience members were invited to sit and listen to speeches detailing how we would fight and win. The campaign was designed around five demands: a real pay rise, slash energy bills, end food poverty, decent homes for all, and tax the rich. But the strategy for how these demands were going to be won was always a little unclear, and once the rallies had died away there wasn’t much for participants to do beyond a round of local demonstrations in October. Their latest activity seems to be setting up a petition to oppose the latest trade union bill, which has so far collected 10,000 signatures. Despite the trade union connection, the movement’s ability to mobilise has diminished, to the point that it now resembles another People’s Assembly Against Austerity. Some critics have suggested that the purpose of the campaign was always to absorb the energy sparked by the cost-of-living crisis and protect the position of the established left from any insurgent movement arising from outside the traditional labour institutions.

More effective were the spontaneously-formed strike support networks which have sprung up in many areas. Structured around WhatsApp groups and facilitated by picket line information made available via Strike Map2, these have built off existing activist networks and brought workers out to support each others’ disputes. However, these groups have not come together to establish any coherent movement structures or demands.

Don’t Pay, established to fight against energy price rises, also had exciting moments. The campaign’s clear demands, effective theory of change (an energy bill strike starting as soon as 1 million people signed up) and a smart funnelling of website signups into postcode organising groups led to a period of rapid growth that both broke out of the left bubble and threatened to put the energy companies under real strain. But after the Truss government, partially due to the pressure placed on them by groups like Don’t Pay, made real concessions on energy prices3 it failed to strategically re-orientate, and so ran headfirst into a brick wall4. Subsequently, the potential crossover of picket lines and anti-bill protests that could have been so promising never materialised.

All in all, the official left has been fundamentally unable to articulate the demands of the strikers at the level of politics. The purging of the left from the Labour Party has not led to a stable reference point that those activists can look towards for political leadership. In this context, it should come as no suprise that public figures have become a rallying point, like Mick Lynch - whose TV news appearances stood out in the middle of an otherwise almost universally reactionary media landscape.

A difficult balance of forces

On the face of it, the balance sheet of the recent strikes is not looking positive. We have yet to see what a national victory looks like. There are an increasing number of bad deals, with unions settling for way below inflation pay rises. The balance of forces facing the strikers seems unfavourable so far. The rail dispute that started this wave off has yet to be resolved, even though settling the strikes would have now been cheaper for the government. There have been many smaller disputes that have ended in good outcomes, but no big victory to refer to. Even more importantly, the horizon of ‘victory’ seems now to be firmly limited to wage increases - the idea of a bigger political victory that wins something of significance for the whole class seems far away. The potential exists for this revitalisation of the trade union movement to lead into a series of long and very difficult fights. This could end in unions selling out for shit deals, or in relentless year-after-year strikes with little to show for it.

But despite this unfavourable balance of power, the menace of the working-class runs deep. Whatever the terrain, there is always the potential for something to happen. This could be the creation of a new layer of rank-and-file militants with experience of how to organise and strike, or something more dramatic. We have to keep our eyes peeled for what that something might be.

What are the implications?

These disputes are far from over. Strike days keep on coming, and nobody knows what exactly will come next. But whilst it’s impossible to precisely predict the course of struggle, we can do two useful things. First, we can identify what interventions could be made in this struggle to try and increase the political potential of the strike wave. Second, we can reflect on what this sudden surge of action might tell us about what patterns of struggle emerge from our contemporary class composition.

Rank-and-File development

The single greatest political opportunity offered by these strikes is the chance to build rank-and-file networks amongst striking workers. In our workplaces and across our cities, companies, industries and unions, we can start to build connections amongst reps that form the basis for a more powerful and political workers’ movement.

The structure and activity of these networks should be relatively simple:

-

The nature of any rank-and-file network will vary depending on how it’s defined by the workers that start it. They should all bring together representatives and shop stewards, but they can do so along different lines. One example could be a workplace network that connects all the reps in a single work site, regardless of job role and union. Others could be a company combine that connects reps across the country, a city or regional network that brings together reps from all the workplaces in a geographic area, an industry network that connects reps in the same industry, and so on. Each of these forms will be able to achieve different things, and influence any union activity in different ways.

-

WhatsApp groups can be a useful starting point for developing these connections. We all have groups that can create an initial basis for organising, where we discuss issues at work with other workers we trust, or even simply arrange nights out to vent about the boss. But it’s vital we don’t just stop once we’ve taken those easy first steps. Mapping the workplace/industry/area/union should indicate where the network is strong and weak. Picket line visits and simple one-on-one conversations can build the network further from there.

-

These networks can’t be restricted to just WhatsApp and other online platforms: democratically-run meetings are essential for building a deeper mutual understanding and trust, while planning the harder work of sharing ideas and skills, discussing strategy, planning escalation, with the goal of understanding how to build pressure on the bosses and union bureaucracy.

-

Rank-and-file groups can use bulletins to build further connections and spread ideas. Strike bulletins have a particular role to play in updating the rank-and-file on the progress of a dispute.

-

The nature of a rank-and-file network means that they will tend to attract the most committed workplace activists, but that shouldn’t stop you from recruiting less experienced workers, particularly from workplaces with no established rep structure. Being involved in wider networks can help them develop their skills.

-

A rank-and-file network is not the same as a faction that aims to run election campaigns for bureaucratic positions. This isn’t the end goal of organising within a union. Your network should be open to people from different union factions, if they exist, so long as they accept the need for rank-and-file organisation, and commit to respecting the democracy of the rank-and-file network.

-

We should take inspiration from organisations like the Clyde Workers Committee, formed during the First World War, which argued that: “We will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently, immediately, if they misrepresent them. Being composed of Delegates from every shop, and untrammelled by obsolete rule or law, we claim to represent the true feeling of the workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank-and-file.”5

- This moment is a prime opportunity to implement an agitational strategy. This means in unity with other workers getting into scraps against our bosses, and then trying to push the dispute as far as it can go politically. The hope is that we can make the transition from small scale disputes over how much we’re paid into bigger fights over how society is organised. We’ll discuss this question of agitation more in future issues. If we succeed in building these networks rapidly, they then could begin to challenge union leaderships for bottom-up control of the strike wave. In unions where there is more democratic space, there may be more cooperation from the bureaucracy. Elsewhere, we may have more combative relationships with union staff and leaderships. Independent rank-and-file bodies can push for tactical escalation, and when brought together on a bigger scale they could even start to represent the political demands of the strikers independently of the official trade union movement. In short, they could change the character of this strike wave completely. Clearly we are very far from this right now. As discussed above, the rank-and-file have yet to establish control over any of the major ongoing disputes. But any movement in that direction would be a major step forward for the class struggle in Britain, even if the disputes they emerge within end in stalemate or defeat.

A new pattern: Class struggle on a heating planet

The pursuit of profit has carried us from the first enclosures of common land to the precipice of environmental disaster. Today, the drive to accumulate capital has become a death drive, as our society plunges head first towards at least two degrees of warming this century. It is becoming increasingly clear that our experience of the resulting collapse will be defined by a relentless downward pressure on our quality of life, punctuated by crisis after crisis. There will be more extreme weather events, mass migrations, the passing of new diseases from animals to humans, and unpredictable new social conflicts that emerge. The seeming consistency of “business as usual” will be interrupted by breakdowns in production and logistics across the world. These interruptions may be brief and peripheral at first, but will grow increasingly prolonged and destabilising. As a result there will likely be new struggles over consumption as unorganised workers and sections of the class with limited workplace leverage face real and serious barriers to their continued survival.

In this sense, the events from early 2020 to the present give us a glimpse of what life could be like in the decades to come. The current strikes are a response to the steady increase in the price of basic commodities, a trend which is likely to persist as the cost savings associated with lean production systems and globalisation are countered by increasing ecological damage. This was a topic of elite discussion at the recent World Economic Forum in Davos6, as the big manufacturing capitalists stressed the need for a multi-year transformation of supply chains to increase resilience. Blackrock, the world’s largest asset manager, agrees with this approach. Their 2023 prediction is for a future shaped by “brutal tradeoffs” and permanently elevated levels of inflation, which will stay high unless central banks raise interest rates to extraordinary levels and provoke severe recessions.

But could this constant increase in prices be cushioned by increases in wages? If workers get large wage rises, it shouldn’t matter if food prices rise by 17% a year. However, such wage increases would either have to be funded by an increase in the overall amount of value produced by the economy, or by a reduction in the share of value paid to capital in the form of profits. We will turn to the second possibility in a moment, but first it is essential to understand that a long-term return to significant GDP growth looks like an increasingly remote possibility. The International Monetary Fund predicts that the UK economy will shrink by -0.6% in 2023 in a short-term recession, but the prospects for long-term growth also seem bleak. Service-heavy, deindustrialized economies seem fundamentally unable to produce significant increases in the productivity of labour. Capitalism’s history has been one of ceaseless innovation: the division of labour, the spinning jenny, the steam-powered factory, the assembly line, containerisation - we can tell the story of the system through the names of the innovations deployed against the working class. But now, technological change is sluggish. The computer revolution can famously be seen “everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” Algorithmic management, the great technological development of platform capitalism, does little to increase the productivity of labour. Instead, it mostly automates the unproductive labour of supervision, thereby saving costs and sweating labour that little bit more. We are living in a remarkable moment, with a simultaneous process of ecological breakdown, technological stagnation, and widespread economic stagnation, potentially leading to extreme instability. The hopes of governments and their media parrots that things will soon go ‘back to normal’ could not be more misplaced.

So, to turn to the second option, will capital willingly reduce its profits to support workers’ quality of life? The answer is obviously no. If there is a static sum of value in the economy and prices are rising, then either labour or capital will have to bear the pain, and neither will do so voluntarily. The pattern of class struggle on a heating planet will be a zero-sum distributional conflict. While this may start in the workplace, it will be punctuated by occasional flashes of intensifying activity - be they mutual aid or food riots - clustered around specific crises.

For the workers’ movement, then, the near future looks like a series of desperate defensive battles against real wage cuts, in which we try to force the bosses to bear the costs of inflation by shrinking their profits. But without the relief of a return to growth, this fight will have to be refought every year. This looks like a setup for a period of persistent conflict. In the face of such an attritional environment, it’s likely that trade union leaders will be tempted to form a social compromise with a (likely) Starmer government in 2024, even if he has shown himself to be anything but trustworthy. But despite the best will of both parties, it’s hard to see where the room for compromise would be found. Unlike in the period of Blairism, a consistent background growth rate of 4-6% seems impossible. This means that redistribution would necessarily involve taking from one class to give to another, not just shuffling the ratio by which new wealth is distributed. The Labour Party, now purged of anyone even rhetorically committed to socialism, will not risk their ruling class connections to please trade unionists, even if those trade unionists complain loudly at Labour Party conferences. Any Labour-Union social compromise would likely be very weak, and face immediate pressure from above, and as resistance increases, below. In the face of escalating social conflict, state authoritarianism (of either blue or red flavour) is likely to increasingly limit the freedom of action afforded within the law to trade unions and social movements. It is in these circumstances, that any rank-and-file networks we build now can become critical.

The post-war victories of the mass factory worker were achieved in manufacturing industries during periods of significant growth. Their context could not be more different from ours. So too will our slogans differ - whereas they had ‘we want everything’ [vogliamo tutto], ours is more likely to be ‘not one step back.’ The argument above is just a first attempt at understanding the emerging rhythms of class struggle on a heating planet. The more thorough discussion of this essential strategic task will have to be left to future issues. But it seems clear to us that this wave of disputes sets the pattern of what is to come. The period of low strikes may be coming to an end, with a new generation of militants coming to the fore as the leaders of a working class engaged in desperate defensive battles in a destabilised global context. In this context, the potential for rapid changes in the balance of forces, both positive and negative, cannot be overstated. This is the start of an era of instability. But we welcome this circumstance – after all, the advantage of small forces is that they can outmanoeuvre the lumbering giants of the state and capital and take advantage of the terrain. Now is the time for building rank-and-file movements. As the late Mike Davis argued, we face a desperate future that threatens the lives of billions of people: “Against this future we must fight like the Red Army in the rubble of Stalingrad. Fight with hope, fight without hope, but fight absolutely.”7

-

Davies, Steve. ‘Leverage campaigns and how they work’. Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data. 30 Sep 2021. ↩

-

Milburn, Keir. ‘Don’t Pay Took Down Kwasi Kwarteng’. Novara Media. 18 Oct 2022. ↩

-

Angry Workers. ‘Reflections on Don’t Pay’. Angryworkers.org. 17 Jan 2023. ↩

-

Gallacher, Will. ‘Clyde Workers’ Committee: To All Clyde Workers’. Marxists.org. 1915. ↩

-

Tett, Gillian. ‘Four is the new two on inflation for many investors’. Financial Times. 19 Jan 2023. ↩

-

Movaghary-Pour, Jalal. ‘Fight with hope, fight without hope, but fight absolutely: An interview with Mike Davis’. LSE Researching Sociology Blog. 23 March 2016. ↩

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Class Struggle and Recomposition at the Royal Mail

by

Wilson Fisk

/

April 28, 2023