After Grady's election - where is the Rank and File?

inquiry

After Grady's election - where is the Rank and File?

by

Sai Englert

/

May 31, 2019

A reflection on the recent general secretary election in UCU

The recent election of Jo Grady as General Secretary of the UCU represents a watershed moment in the history of the union, and it is difficult to overstate its importance. Indeed, the union has only known one General Secretary in its decade and a half of existence – Sally Hunt. It has been run throughout this entire period by an alliance between Hunt loyalists and the ill-named Independent Broad Left.1 This control has been so powerful, that many assumed that the recent election would simply be an exercise in crowning Mark Waddup – Hunt’s heir apparent.

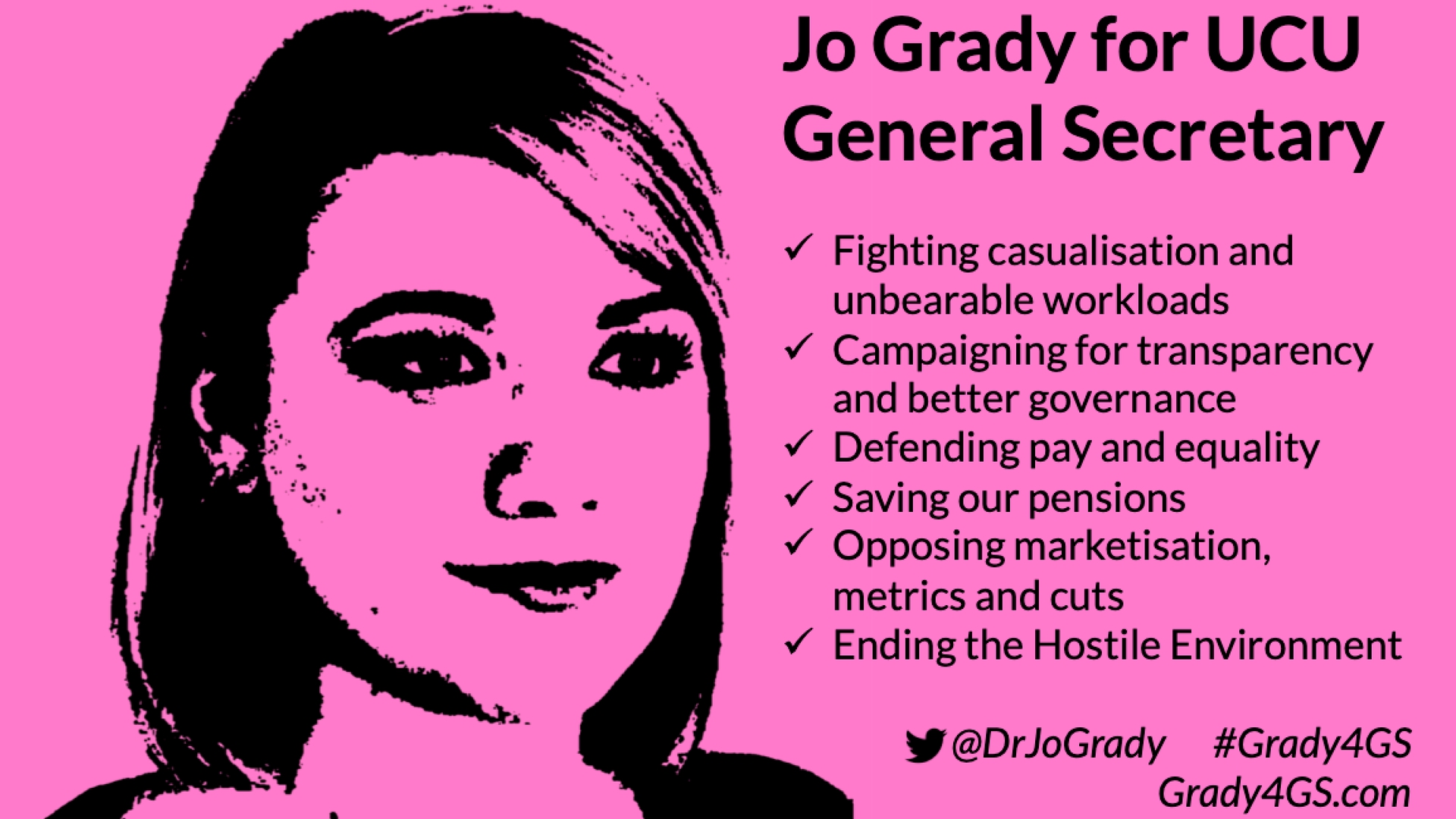

Jo Grady, a union activist and co-founder of the USS Briefs collective, came to the fore in last year’s prolonged strike over pension reforms in Higher Education. She has built a name for herself through the very active role she has taken in challenging employers and pension providers since. Her campaign was not only impressive because of the radical nature of her platform, as well as the halt she proposes to business as usual in the union, but also because she stood independently from any of the existing factions inside the union.

Against all odds, her platform and her independent stance galvanised members and allowed her to garner nearly 50% in the first round of the largest vote for GS elections in the union’s history. Her victory is as significant as it is remarkable. It marks the long term shift of the union membership to the left - as well as the growing discontent many have felt at the lack of any credible strategy or leadership coming from the union, despite the severity and relentlessness of the attacks on post-16 education for at least two decades (see last year’s article, Looking Back in Anger ). College and University workers need and want change, and this is what Grady offered. The challenges ahead are severe however, and this piece is intended to start a process of reflecting on how we can overcome them.

Firstly, it should be pointed out that – perhaps obviously – winning an election does not translate automatically into taking over the union machine. Indeed, after such a long period of control by one faction, the union’s full time staff is deeply wedded to a particular way of doing things and a set political vision. If anyone doubts that Grady will step into a machine that is aggressively opposed to her platform, remember how the full time staff of the union repeatedly shut down the UCU’s congress to stop the membership from holding Hunt to account over her repeated attempts to undermine the USS dispute. These same people are still in place and will do everything to undermine the new GS or box her into the existing mould.

The recent attempt by a similarly radical leftwing candidate to take over the NUS – Malia Bouattia – is another example of how winning elections does not equate to taking over the union. Bouattia found herself isolated within the union machine and increasingly cut off from her base, as she became stuck in endless conflicts over funding allocation, policy implementation, and even the drafting and circulation of communication to the membership. At the same time, repeated leaks to the press and coordinated smear campaigns from within the union further immobilised Bouattia’s team and broke their ability to implement the changes they aimed to put in place, while making the actual job of running the union and taking the fight to vice chancellors and the government impossible. Something which also has echos with Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party.

A meeting between Grady and Bouattia might be a good first step to discuss potential challenges and pitfalls. Another important example is Mark Serwotka’s election at the head of the PCS union. Indeed, Serwotka was also elected on a radical ticket with the support from a membership in open revolt against the union’s traditional and more conservative leadership. Serwotka took a very direct approach towards the existing staff. At an all staff meeting he presented the changes his leadership would represent – both internally and in terms of political direction. He told the staff that he wanted them all on board but that he understood this would mean too much change for some and offered them a payout package. Many of the old full time team left and Serwotka was able to staff the union with political allies who shared his vision, turning the PCS for many years into one of the more militant unions in the UK.

Crucially, these struggles will not be won within the confines of the union bureaucracy alone, or perhaps even primarily. They will necessitate the active participation and continuous pressure of the union membership. It was the NUS machine’s ability to cut Bouattia from her base that effectively immobilised her, and all UCU members will need to actively stop this from happening to Grady. This is no small task. Indeed, the question will now be how to turn the excitement and mobilisation at the ballot box for Grady into an active, organised, and attentive membership that will be able to support Grady against the old guard, while also keeping her focussed on the union’s grassroots.

Here a serious problem arises: the lack of any real rank and file movement within the UCU. Indeed, despite the repeated description of Grady as a rank and file candidate on social media by her supporters, this is not an accurate depiction of the situation. Grady is an independent – in the sense that she is not aligned with an existing faction in the union – and a member of USS briefs. She is politically to the left of the union and is standing on a militant manifesto. These are all important aspects of her successful candidature. However, there is no organised rank and file in the UCU and all attempts to form one since last year’s strike have failed to attract more than the usual suspects.

What is more, Grady’s election also illustrates the inadequacy of existing left networks in the union. Indeed, UCU left – the main opposition to Hunt within the union’s leading bodies since its formation – has also repeatedly failed to effectively mobilise and represent the anger coming from members. Whether during last year’s strike, when most important initiatives by members took place outside of its structures, or in these recent elections, where the UCU left candidate came last,1 it is clear that the faction inside the union has not been able to galvanise the existing anger and growing militancy of members. The fact that a newcomer on the union’s national stage managed to do what UCU left has failed to achieve in nearly two decades is an evident damning indictment of its effectiveness.

The danger ahead is then that Grady’s leadership, to succeed in implementing her program will need to sustained mobilisation of the union’s rank and file, but that the last year has demonstrated the lack of an existing effective network that can deliver this organised engagement of the base with the union’s leadership. And while Grady will no doubt be able to count on the support of UCU left’s numerous representatives in the union’s national bodies, she will have more trouble finding the necessary social weight coming from the membership. This problem will need to be solved, and rapidly, not by Grady and her team – who will have their hands full in struggling to take control over the union’s internal machine – but by activists inside the union themselves.

One important step in that process will be the sharing of ideas, debates, and discussions relating to union business and industrial struggle within the post-16 education sector. It is for this purpose that we are re-launching the University and College Worker, this time as a blog to help facilitate this process. Born in the 2018 USS strike as The University Worker, it was a bulletin that published accounts by workers about the strike locally and encouraged the sharing of ideas and tactics between different local activists. It was the also a facebook group which brought together thousands of union members and was at the origin of the 11,000 strong petition that opposed the selling out of the strike half way through by Hunt’s leadership. This bulletin will not be the solution to the lack of an existing rank and file network, nor does it claim to become it in the future, but we hope that it can become a platform for debate on strategy and tactics, a place for university and college workers to share reports from their local campaigns and build connections nationally, and re-energise member engagement with the union outside of elections.

Grady’s inspiring election is a sign to all of us that business as usual is no longer enough and that there are real opportunities for radical opposition to the government led destruction of post-16 education. Now is the time for all of us to seize the opportunity it represents to strengthen our organisation, so we can take the fight to all those who have been attacking and undermining education - and win.

-

Far from being independent, broad, or on the left, the IBL is a Communist Party led, highly conservative faction in the union that has consistently opposed industrial action or confrontation with employers or the government. ↩↩

-

An excellent candidate, who this author in fact supported in the election. The issue is one of political organisation rather than individuals. ↩

author

Sai Englert

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

A Post-Strike Proposal

by

Jamie Woodcock

/

April 15, 2018