The University Strikes, as seen from Birkbeck Library

by

Anonymous library worker

April 28, 2023

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

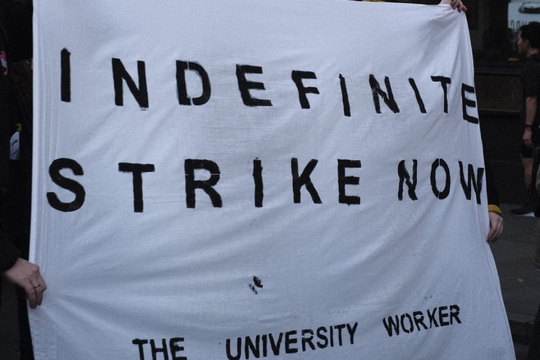

On strikes, restructuring, and fighting for a militant industrial unionism

inquiry

The University Strikes, as seen from Birkbeck Library

by

Anonymous library worker

/

April 28, 2023

in

In and Against the Union

(#17)

On strikes, restructuring, and fighting for a militant industrial unionism

In 2023 Birkbeck, a constituent college of the University of London, is celebrating its 200th anniversary. Founded as the London Mechanics’ Institute by a proponent of adult education, George Birkbeck, it went on to have a proud history of providing higher education to those generally excluded from it. To this day it is one of few universities in the UK to provide in person evening classes, allowing those with jobs or other daytime responsibilities to study for degrees. However, in recent years Birkbeck has been riven by a management who are pushing through a controversial restructure plan, that has threatened compulsory redundancies and an increase in staff workloads, as well as creating a chaotic work environment which has severely damaged staff morale.

I have worked at Birbeck in the library for a few years. In that time I have taken part in strikes, either by not crossing picket lines in solidarity with UCU workers or on an official strike through my union, Unison. Since the pandemic I have become more involved in union activity, joining the branch committee and getting involved in branch organising. Through that time Birkbeck has gone through a series of changes, including an initial 2019 severance scheme and the COVID-19 pandemic which fundamentally changed how work was done within the university. In addition to my work I am also studying at the college, facilitated by a (now cancelled) staff study scheme and Birkbeck’s continued commitment to evening education.

The Crisis

There is no disputing that Birkbeck as an institution is in a difficult financial situation. Over the last two academic years, the university has attracted significantly fewer students, severely impacting revenue. This is due to a series of interlocking factors. The pandemic of course played a significant part in a fall in numbers, but there are wider issues such as the increasing competition in the sector for Birkbeck’s bread and butter - in-person and online education for those who are in work. The hit in student numbers has caused a sizeable deficit which needs to be addressed if Birkbeck is to continue functioning as an highly regarded university.

The causes of the crisis, its seriousness, and proposed solutions are, however, bitterly contested. Senior management had advanced brutal cuts, with up to 150 roles initially under threat, with a wholesale restructuring of schools and departments already underway. This has been justified to staff through near-apocalyptic pronunciations via internal communications. Workers have made a different argument. The two biggest unions at Birkbeck, UCU and Unison, have commissioned independent research from researcher Andrew Mcgettigan that undercuts some of the alarmist rhetoric: Birkbeck is in a far more favourable position than universities facing similar crises. The institution has large reserves, and is free from fulfilling onerous debt obligations that have plagued other institutions, such as Goldsmiths. The situation is certainly a sober one, but does not necessitate the course of action proposed by senior management. Unions have rejected the need for any compulsory redundancies and have pushed for a slower pace of change within the university that focuses on a clear growth plan that will rebuild student numbers.

Compulsory redundancies have now been ruled out for school-based admin staff, which is a welcome development. But this is only because so many staff have already voted with their feet and have either found jobs elsewhere or taken up voluntary severance. Indeed, the severance scheme was so vastly oversubscribed that management rejected or paused the majority of requests. Over 20 academic roles are still at risk of compulsory redundancy, and staff in central services have not yet been brought into scope. The departures have emptied entire teams, almost all of the school of management admin staff have left, and the entirety of front-facing student mental health welfare has been lost. Management has made a consistent, increasingly implausible, assertion that such changes will not negatively affect the student experience. To be clear, such a claim does not hold up to scrutiny. Even if roles are refilled, or a proper internal recruitment program is carried out, years of institutional experience are being lost.

The Fightback So Far

Unions at Birkbeck, the two largest being UCU and Unison, have mobilised against the restructure as initially proposed by management. Opposition has come via official channels, in the official negotiating committees and a wider consultation, and at the grassroots, amongst workers and students. An encouraging development has been the broadening of discontent beyond the usual layer of activists, and across the institution to sections of workers who are not usually involved in union nor strike activity. There have been some useful convergences: the local situation has fuelled strikes and activity in the national pay dispute. Some have gone on strike or attended pickets when they would not have previously done so. More concretely, the last strike day of 2022, which featured a national UCU demonstration, coincided with an important governors meeting in which the restructure was to be heavily discussed. This provided militants with the opportunity to build a large and loud presence outside the meeting, and allowed sympathetic staff governors to address the crowd after the meeting.

There have also been some welcome signs of broader organising within departments under threat, although this has been sporadic. Union branches have also done a good job of organising joint member meetings to plan for specific actions or to respond to events as they happen. The public campaign has excelled at highlighting the voices of students and workers of specific departments under threat, whilst maintaining a united front that refuses openings for a divide and rule logic to take hold. It has also extended the campaign further out into the media, forcing management to respond publicly. Another recent development has been the founding of a Birkbeck action group to bring together staff and student activists and further develop rank-and-file organising.

Organising has undoubtedly been held back by union bureaucracy. Unison’s bureaucratic structures for approving strikes are slow. Regional and national structures require three weeks advance notice to approve any strike action (the law requires that employers are notified fourteen days in advance). Information coming from the region has often been inconsistent. Meanwhile, UCU’s fractious internal debates, played out over social media, have also muddied the dispute. A reluctance to coordinate with other unions on the part of national UCU structures has left the smaller Unison branch scrambling to get its authorisation processed in time.This has made coordinating strike days difficult, and inevitably some strike days have only seen academic staff out on strike. Indeed, at the time of writing, coordinated action will not happen for more than half of the UCU strike days due to Unison’s ballot mandate expiring and UCU’s short notification of strike action. One response to the problem is the development of rank-and-file networks and structures outside of union bureaucracy that can communicate dates ahead of official announcements - something that already happens on a sporadic, ad hoc basis. More generally, our branch has insisted on an independence in decision making and discussion within committee meetings, with regional officers generally relaying points of information or clarifications of union procedure. Our position within a cluster of other branches in Bloomsbury has encouraged organising between branches, although this could be deepened.

How We Can Escalate Our Struggle

As discussed above, there have been some concessions from management (although they would never admit it). In early January they released an update on their plans to staff, which softened some of the apocalyptic language of previous communications, and had in principle accepted some of the unions’ alternative proposals, such as the development of a growth plan and the institution of expanded teaching hours. However, there is a need now for escalation and push for an outcome favourable to workers, especially after a formal governors vote to approve compulsory redundancies as part of the wider restructure. Escalation can be achieved in two ways, broadening activity within the workforce and intensifying struggles through direct action.

At times, activity at Birkbeck has excluded some of the most disadvantaged workers - primarily cleaners and catering staff. This lack has in part been because those workers are not directly affected by either the national or local disputes, but their struggle is vital and the inclusion of their voice would benefit everyone. Despite finally being brought in house in 2021, cleaning and catering staff are still only paid the London Living Wage, which pays less than the equivalent grade on the Birkbeck pay scale. Cleaning staff in particular have encountered problems with understaffing and overwork, as well as an inflexibility on the part of managers to accommodate health concerns. Such issues should be a vital part of the campaign and have deep resonances with what is going on elsewhere in the institution. Aside from this, department organising should continue, and structures that have been established now, such as the new action group, should be brought forward to engage with future struggles.

The other avenue for escalation is a campaign of direct action. There is a role here for students and other outside supporters who have more leeway to engage in direct action than workers employed by the institution. As Charlie Macnamara noted in his recent analysis of the present strike wave, direct action should be a vital component of a campaign, complementing strikes and other more symbolic means of applying pressure.[1^] Student activists at Birkbeck have engaged in important work around building support for the strikes and have made representations to senior management via the students union. A sustained campaign of direct action organised to coincide with strikes would represent a significant and welcome escalation. It is only a benefit that there is a long legacy of student-led direct action in Bloomsbury, particularly in SOAS and UCL.

Throughout this process, management’s strategy has been to deliberately foster a sense of fear amongst staff: for their jobs, for their colleagues and for the institution to which they have dedicated years of their working life. It is time for workers, supported by students and those outside of the university, to refuse this fear and to push for a long term change of the balance of power within Birkbeck. Now is the time to win.

Featured in In and Against the Union (#17)

author

Anonymous library worker

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Welcome to the future: this strike wave is just the start

by

Notes from Below

/

April 28, 2023