Trade union organisation

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

March 21, 2023

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

On contemporary struggles within, against and outside of trade union organisations.

inquiry

Trade union organisation

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023

in

The Class Composition Project

(#16)

On contemporary struggles within, against and outside of trade union organisations.

There are two parts to the story of trade union organisation in Britain. The first is the overall statistics and trends on union membership, while the second is the recent disputes - including the hot strike summer in 2022.

The UK produces statistics on the overall membership and scope of trade unions, both through statistical bulletins from the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and the Office for National Statistics, as well as the Certification Officer. This chapter draws on the “Trade Union Membership, UK 1995-2021: Statistical Bulletin” and the Certification Officer Annual Report. The political composition of the working-class is obviously not solely defined by activity within trade unions, and it is worth starting by saying that many of the statistics in this report take a simple yes/no measure of trade union membership. This can include rank-and-file militants all the way across to those who just pay their monthly fee. It does, however, provide a starting point for thinking about the state of the institutional labour movement in the UK.

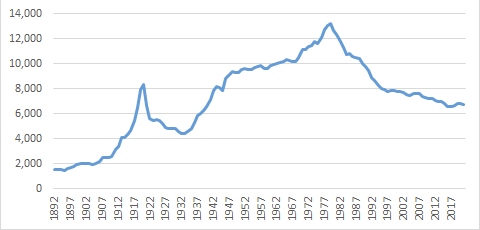

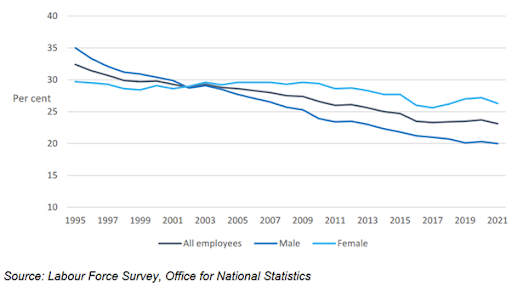

The headline figures for 2021 are that there were 6.44 million trade union members. This year was the first drop in membership after 4 years of growth. As a proportion, this meant that 23.1% of employees in the UK were members of trade unions, down from 23.7% in 2020. This is the lowest rate since the start of the dataset in 1995. Union membership growth has been driven by new female members since 2017 and the fall this year has also been larger with female membership.

The chart shows the longer-term trend of union membership since 1892, including the peak in 1979 of 13.2 million members, then the decline through the 1980s and early 1990s. The decline slowed after 1996 with some moments of slight growth, although trending downwards.

In the following pages, we reproduce a series of figures that illustrate shifts in the composition of trade union membership in the UK.

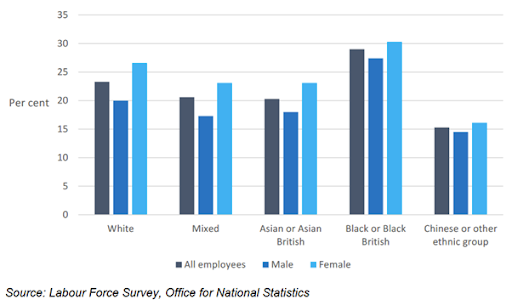

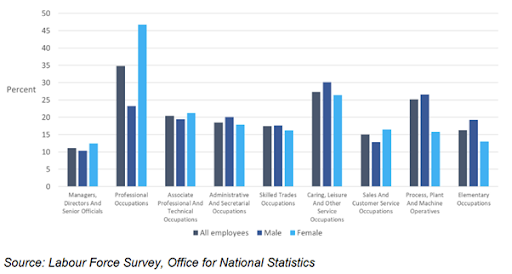

As you can see from the figures, from the 2000s, while membership of trade unionism fell, the proportion of women in trade unions increased. 26.3% of women are members, compared to only 20% of men. In terms of ethnicity, Black or Black British workers are the most likely to be members (29%), followed by White (23.3%), Mixed (20.6%), Asian and Asian British (20.3%), and the lowest amongst Chinese or other ethnic group (15.3%). Workers born in the UK were much more likely to be members (24.1%), compared to non-UK born workers (18.6%).

Workers with higher qualifications were much more likely to be members of trade unions. For example, workers with a degree (27.5%) or other form of higher education qualification (27.5%). Those with A-levels (19.5%), no qualifications (18.1%), GCSE A-Cs (17.9%), other qualifications (not A-Level or GCSE – 15.7%) all formed smaller percentages of overall trade union membership. Those in large workplaces were much more likely to be members (30%) compared to smaller workplaces (less than 50 workers – 14.9%).

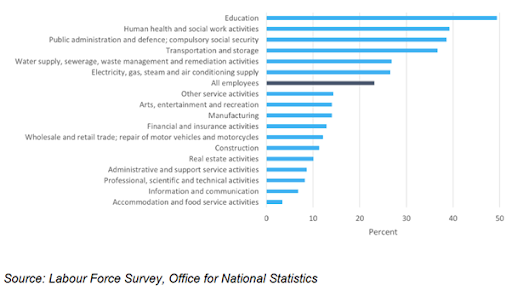

Trade union density is highest in professional occupations (34.8%). In terms of sectors, workers in education are the most likely to be members (49.4%). Then there are five sectors in which workers are more likely than the average to be members: “Human health and social work activities”, “Public administration and defence; compulsory social security”, “Transportation and storage”, “Water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities”, and “Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply.”

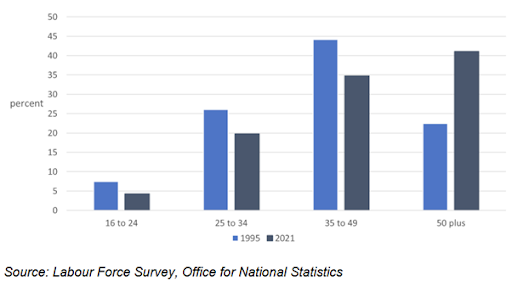

The last figure shows the age distribution of trade union members. This compares the figures from 1995 to 2021, showing that the average age of members skews older, and older than it did in 1995. For those aged 50 or older (41.1%), between 35 to 49 (34.8%), 25 to 34 (19.8%), and between 16 and 24 (4.3%).

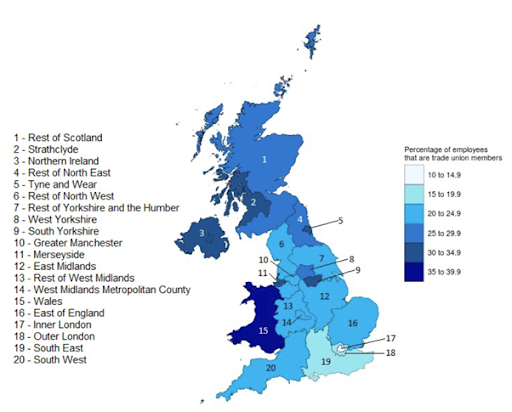

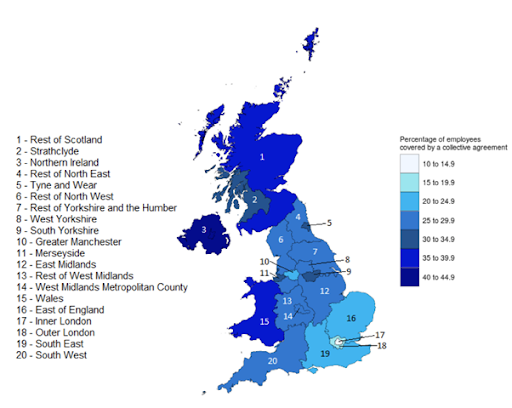

There are also significant regional differences in both union membership and coverage of collective bargaining.

Unions in Britain

The Certification Officer in the UK certifies the independence of trade unions, ensures statutory compliance (including with annual returns), and deals with complaints. The Annual Report includes a list of all currently certified unions in the UK. In 2021 there were 128 registered unions, of which 4 are federations (Confederation of Shipbuilding and Engineering Unions, International Transport Workers Federation, Trades Union Congress, and Workers Uniting). Trade unions are required to submit annual returns to the Certification Officer which include data on finances, strike ballots, and membership. Not all the annual returns are up to date, with some unions only having the previous year’s return. As of May 2022, the combined returns have a union membership of 6,721,434 (a higher figure than the other estimate). We have included the full list of unions and the number of members that have completed annual returns included in the appendix.

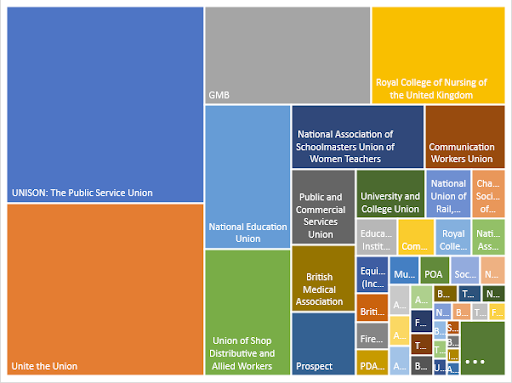

There are 12 unions with over 100,000 members, 28 smaller unions with more than 10,000 members, then 40 smaller unions with more than 1,000 members, and 37 unions with fewer than 1,000 members. This does not count the 4 federations or the 7 unions without any annual returns.

Within the 12 large unions, the membership is dominated by UNISON (1,417,637) and Unite (1,246,429), with another tier below of GMB (601,907), Royal College of Nursing (483,683) NEU (457,368), USDAW (402,958), and NASUWT (311,919).

UNISON

In many ways, UNISON is the embodiment of the modern trade union movement, not least because it constitutes approximately 1/5 of total trade union membership in Britain with 1.4 million members. It has majority female membership and draws most of its membership from the public sector. Like the other two large general unions (Unite and GMB) it has recently changed general secretary with Christina McAnea replacing Dave Prentis in 2021. However, UNISON is currently beset by infighting with the majority faction on the NEC (Time for Real Change) struggling against the general secretary. Equally, UNISON’s large membership does not appear to have produced enough stewards, as demonstrated by its recent failures in the industrial action ballot in local government and low turnout in the indicative ballot in the health sector.

Although UNISON faces the additional obstacle of obtaining a 50% yes vote in most of its ballots (as many of them will be important public services as defined by the 2016 Trade Union Act), other unions have demonstrated that this is not an impossible threshold to breach. Recently, Unison members in higher education have balloted for strike action over pay in September. 22 out of 92 branches successfully met the ballot threshold and are planning industrial action for the start of term. While still a fairly disappointing turnout, it shows that these obstacles can be overcome, and potentially paves the way for more workplaces to join.

Unite

The union with the biggest media footprint (in no small part on account of its close ties to the Corbyn leadership of the Labour Party) and the second largest union in the UK (with 1.2 million members), Unite is arguably the most interesting union. Like UNISON, Unite has a new general secretary, Sharon Graham. Graham wants to reorganise Unite’s structures and reorientate it on industrial lines instead of regional, with the methods of accomplishing this including establishing worker led combines and focussing on the most powerful employers in each sector. Despite Graham’s emphasis on returning to the workplace, it would be an exaggeration to claim that this is a shop-floor lead project. Although Graham does enjoy support from a lot of shop-floor activists, this is a result of an effective top-down approach from the Organising and Leverage department that Graham ran prior to becoming General Secretary. Indeed, it could be argued that, in practice, Graham is attempting to expand the methods of the organising department across the rest of the union. However, the extent to which this is viable remains to be seen. While Unite is currently involved in more disputes than before (a trend across the trade union movement), Graham does not currently have a majority on Unite’s Executive Council, and it remains to be seen if she will secure one at the next elections in 2023.

Unite has been involved in a series of disputes, including with refuse workers, buses - including a victory in the North West following an indefinite strike - and a strike at Felixstowe Docks. 1,900 dockers took strike action over pay from the 21st to 29th of August, for their first strike in thirty years. The port, owned by CK Hutchison, is the largest in Britain, handling almost half of all containers that come into the country.

GMB

GMB (which is not an acronym) has 600,000 members. It is another union that changed general secretary in 2021. Tim Roache stepped down amidst scandal of sexual harassment and discrimination within the union, revelations of which are becoming more common across the movement. Gary Smith, who previously was the union’s Regional Secretary for Scotland, won the subsequent contest. GMB is a difficult union to analyse as in practice its regional secretaries wield considerable influence in their respective regions, meaning that the union’s strategy and policies can vary significantly from one region to another. There appears to be a split in GMB about how best to address its falling membership. Some in the union have advocated trying to expand into the already well-unionised public sector, while others have looked to the private sector. GMB has signed two controversial voluntary recognition deals in partnership with the gig economy platforms Uber and Deliveroo, despite other smaller unions actively organising these workers. Looking ahead, the most significant test for GMB will be what future can it secure its workers in the energy sector, given some form of transition towards renewable energy is inevitable; if this is left solely to capital then it will be at the expense of workers.

CWU

The Communication Workers Union (CWU) organises 189,000 workers mainly in two sectors: postal workers in the Royal Mail and telecommunication workers at a range of companies including BT, O2, EE, and more. In 2020, the union established the United Tech and Allied Workers to organise workers in the technology industry.

The CWU called successful strike ballots at BT and Royal mail in 2022. 40,000 workers at BT and Openreach were balloted after the employer imposed a £1,500 flat rate wage increase (around 3-5%), which falls well below inflation. Openreach engineers voted for action by 95.8% and members in BT returned a 91.5% cent majority for strikes. The union called two days of strike action on the 29th of July and 1st of August, with a further two days on 30th and 31st of August.

Workers at Royal Mail were balloted by CWU following a 2% pay offer. They voted 97.6% in favour of strike action, calling national strike days on the 26th and 31st August, then the 8th and 9th September. Notes from Below collected two reports from striking postal workers. In the first report, an anonymous worker explained:

What are the reasons for your strike action?

Like most people in this country, because I need more money to live cos everything is fucking expensive. Another reason, though, is that the work is getting harder and harder. I started working at Royal Mail three and half years ago, since then the workload is always increasing: walks are getting longer, and the managers who allocate us these works haven’t even delivered to these postcodes. Recently some newer managers have been hired who have never even been posties. Our walks have been revised to be longer because apparently we’ve been finishing too early, but in reality this is because many posties work through their breaks or come in earlier so they can finish earlier. They shouldn’t do this but the reality is lots of them have commitments, i.e as carers or to try and beat rush hour traffic (my office is in London, but many colleagues of mine live in Surrey, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire). The managers don’t say a thing when staff do this, but are more than happy to enforce extra work on them despite knowing their respective situations. The big issue with these revisions is that they seem to be based on the workload we have in the summer season, which is a lot less. Come winter I don’t know how we’ll cope when the workload doubles, if people are going an hour or two over now, that could be 3-4 in winter. Sure overtime is great, but so is our physical well-being, and we need sleep and rest for this job.

Investment in us, with regards to equipment, is dire. There aren’t enough bags and trolleys, so more often than not I find myself having to load my trolleys (if I can find one!) with more items than they’re capable of delivering. Because of the sheer volume of work, we’re forced to cut corners around item security to get stuff delivered, such as storing drop bags for walking-only posties in unsecure locations or literally running to get stuff delivered. Vans are insufficient, and more often than not, they are too small if you’re having to share a van with another colleague. We have a lot of crappy hire vans that we use at our office, and I can imagine they cost a lot to rent.

Royal Mail wants us to come in on Sundays as part of their ‘agreement’ for a 3.5 percent pay rise, but this is unacceptable. For so many of our colleagues Sunday is important:it’s the only day they’re guaranteed to spend time with their families,as many of us work Saturdays; it’s the day they go to church; it’s the day to go to the football. Did the lord not say to respect the Sabbath day?

In general, more than anything, I want better conditions. I love this job. I love walking, the fresh air, and driving my van with the radio on full volume - but it’s taking its physical toll on me. I’ve developed various physical injuries because of this job, including chronic shoulder pain from carrying a bag full of mail everyday, early osteoarthritis in my knees (I’m 29!) and sleeping problems from the stress and waking up at 5am every morning. At this rate I’m not sure if I can keep doing this.

How would you describe your strike tactics?

To be honest, from how things seem at our office, everything is pretty centralised around the union with regards to organising actions. I remember during the ballot we were getting shit loads of texts and emails to remind us to vote, but now the strike is on, not a thing. Not even info about pickets at my own office. For the most part I try to keep myself out of wider national Union activity and focus more on stuff in my office, as I’m not comfortable with the level of gatekeeping by older union officials and bureaucrats.

What comes next? What avenues are there for escalation?

I’m not sure, I think if this strike extends into the winter period, ordinary people will really start to feel the impact as it’s the busiest period. So far we have only announced 4 days of action, and I don’t think that’s enough. The offices depend on staff doing over-time work, so if the union was to try and get members to possibly do a ‘work to your time’ initiative, that could really disrupt Royal Mail. Doing this in tandem with strike action could be very effective.

How does this strike relate to struggle more widely?

The Tories have always tried and in many cases succeeded in cracking down on organised labour. Eventually though, there will come a breaking point, where people just won’t care. If you’re going to starve whilst being employed versus whilst being unemployed, what does it matter? If things carry on as they are, and the wealth disparity increases, I can envision a lot more unofficial strike action, like that at Amazon this year. The issue is how do the Unions deal with this? Since they can’t exactly come out in support of such actions (due to risk of being sued). Eventually they’ll have to embrace the fact they will be forced to turn to illegal measures if they need to stand up for their members.

In the second report, another anonymous postal worker explained:

What are the reasons for strike action?

Royal Mail have enforced a 2% pay rise linked to unacceptable changes. They have ignored and side stepped the union and are attempting to reduce our terms and conditions to the rock-bottom standards across the rest of the industry. This includes an end to fixed finish times, lots of work going unpaid, and the present workforce taking on Sunday duties.

How would you describe your strike tactics?

Our workplaces are being picketed, even when management has closed them due to inactivity. That means that both the work sites with staff still working and those without are all picketed. Pickets vary in size but most are very well attended - these are popular actions both within the workforce and the public. The CWU have organised some events around the Royal Mail central offices in London, but so far nothing else more locally around the country. After the first day of strike action, aside from holding the line so far with the majority of union members out, no leverage is clear at this point.

What comes next? What avenues are there for escalation?

We are awaiting moves from union leadership in regards to escalation. The government is no doubt involved here - as they are with the RMT disputes - as they cannot be seen to lose to a big union like the CWU. However, they are likely to take a serious hit if this goes on, so I can see them backing down soon; most likely before the third day of strike action.

How does this strike relate to struggle more widely?

Politically right now we have no representation for working class issues in electoral politics. We must band together in our unions and social organisations. Therefore our strike actions must unite; via wider organising like the Enough is Enough campaign or similar movements.

We should oppose the Tories on their plans around these strikes, and everything else, with an unrelenting level of intensity. Our very future and ability to live relies on building a better world away from their greed and savagery.

Additional Notes from strike report submission

Support all strikers, never cross a picket line and now more than ever, do not lose focus or hope. We are closer to victory than ever before in my lifetime.

UCU

The University and College Union has 126,000 members. Like the RMT, UCU has demonstrated a recent appetite for industrial action; unlike the RMT it has not demonstrated the same penchant for success. Established in 2006, the union has been involved in industrial action for a number of these years since. More recently this has involved a long-running pension dispute with UCEA and USS that started in 2018. Initially this resulted in an increase in membership and action. However, the most recent development in this dispute is defeat. In the latest ballot in the pensions dispute in April 2022, only 24 branches from over 60 balloted achieved a mandate for strike action and action short of strike action, rendering the action pointless. The response to this was swallowed up by the union’s bureaucratic processes in the form of a special sector conference and the UCU’s annual congress. The UCU’s other main dispute ‘Four Fights’ has suffered a similar fate.

Unfortunately for its members, the UCU is a difficult union to run. It is beset by internal struggles between different factions which has prevented coherent strategy and tactics from emerging. Its administrative structures are byzantine, and it is in the process of transitioning to a union consistently engaged in industrial conflict while its industry becomes more casualised and marketised. The UCU is preparing for another national ballot over pensions and pay, starting in September 2022. This time, the ballot is aggregated, meaning all universities will be able to go on strike if the vote is in favour and with a turnout over 50% - or the ballot will fail for every university if not.

RMT

The RMT (National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers), widely hailed as the most successful union in Britain because of its willingness to engage in, and capability to win, industrial action, has an impressive record when it comes to defending its members pay and conditions. The RMT’s more confrontational approach to industrial relations is facilitated, on the railways at least, by the presence of TSSA and ASLEF (and to a lesser extent, Unite) in the same ecosystem. This does not mean that all the unions operate in constant cooperation, as shown by ASLEF agreeing to a deal that undermined the RMT in a dispute with Southern Rail in 2017. However, the actions of one union cannot be separated from the actions of the others. As with all unions, the RMT has its own challenges. Their defeat to P&O demonstrates that it is perhaps stronger on the railways than the seas. Equally, it is not immune from internal struggles, as demonstrated by the clash between its last two general secretaries and its executive committee. Furthermore, it may be that the change to working patterns and travel caused by the pandemic mean that, in the absence of a government wanting to encourage rail use, the railways will experience a permanent reduction in use and funding. This could reinvigorate efforts to reduce the labour supply, as already seen with the push to get rid of workers in ticket offices. This could be something of an existential challenge for the RMT.

The RMT has been a key part of the recent hot strike summer. Starting in June 2022, RMT called the biggest rail strikes in thirty years. 40,000 workers, including train staff, signallers, and maintenance, took strike action against Network Rail and thirteen other operators across a series of dates. This was followed by strike action called on the London Underground, involving 10,000 workers. As of publication, this dispute is very much ongoing.

Other unions

The previous sections have highlighted some examples of changes and action from the mainstream unions in Britain. In addition to the RMT strikes, TSSA (Transport Salaried Staffs’ Association) and ASLEF (Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen) have recently participated in rail strikes. The NEU (National Education Union), the largest education union with 457,000 members, is currently balloting for strike action. Formed in 2017 from the merger of the National Union of Teachers (NUT) and the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL), it has seen some action around Covid-19, but is now trying to organise a national ballot. The NASUWT, with 312,000 members, is also balloting for a teachers strike. The hot strike summer has also seen Barristers take indefinite industrial action over the cutting of legal aid fees.

The smaller independent unions like IWGB (Independent Workers’ Union of Great Britain) and UVW (United Voices of the World) have continued to organise vibrant campaigns with migrant and precarious workers. These unions have grown at a rapid pace, but both remain under 10,000 members. We have covered their strikes of migrant cleaners, platform workers, and other campaigns extensively in Notes from Below.

Hot (Wildcat) Strike Summer

In addition to the strikes covered above, there has also been a series of wildcat strikes and walkouts in Britain, including in food manufacturing, offshore oil rigs, and by construction contractors. One of the most exciting and well-documented of these strikes were the wave of wildcat strikes that swept through Amazon warehouses. Notes from Below collected worker testimonies of these strikes.

As one anonymous Amazon worker reported:

The whole time I’ve been working at Amazon, everyone I know has had to work hard and been pushed to their limit every day. Despite this, we have never gotten anything more in return, not even nice feedback from our managers.

After these and other continuing problems, they told us on Wednesday that they are going to increase the pay rate by only 35p an hour. Of course no one was happy about this. So a group of us went to speak to management saying that we need an explanation and a good answer from the GM (General Manager).

In reaction to the news that Amazon would only give us a 35p pay rise, many of us stopped working on Wednesday afternoon. We hadn’t planned to walk out beforehand, but the news of the 35p pay rise encouraged many people to do something. I think people in every department joined, with at least 200 workers involved. After we stopped working, they told us to go to the largest room in the fulfilment centre, in order to have a proper conversation. When we got there, all of our managers, area managers, HR, and loss prevention officers were looking at us all. None of them had a clue about what to do with a large group of angry workers.

The next shift - the night shift - joined us with a massive strike. However, we still didn’t receive any answers from the GM. They just told us the same thing that they told those of us on the day shift: “if you’re not gonna work, you will not be getting paid.”

The next morning on Thursday, everyone was still mad. We were still disappointed by the 35p rise Amazon was offering. We therefore decided to strike again from 8am until we got an answer.

Soon after we started striking, the GM came over to tell us that it is perfectly fine to protest, but that we were not going to be paid for staying in the fulfilment centre without working. If we wanted to be paid, we needed to go back to work. They then told us anyone who did not go back to work was going to be automatically clocked out at 08:30. This gave us all 10 minutes to decide whether or not we were going to stay on the same team and continue striking. The majority of us stayed in the canteen where we were striking. Management’s threat scared some people into going back to work, as they couldn’t afford to lose any pay.

After almost three hours, management still hadn’t gotten back to us. As well as this, on the Amazon work app, we were still logged as being at work, meaning the GM had not actually clocked us out like they had threatened to.

We decided to go to the GMs office and demand to talk, but they told us that it was “not safe to have a conversation in here.” After the march to the office, HR came out again to invite eight more people to a ‘round table.’ This of course led to nothing, with the GM again being almost silent, not knowing what to say to us. These eight workers spoke to them about the many problems at the fulfilment centre, and how their attitude and reaction to our protests was very disappointing. They also explained to them that even when we accept everything, meet our targets, and work extra hard on prime days, we are still treated poorly. They told them that when we have a problem, we cannot even speak with a manager, because they are always very rude and ignorant with us. And on top of all this, they explained, we have only received a 35p pay rise, which is a joke. Like before though, this message was not even communicated by the GM to their higher ups, with them showing no empathy for us. There is a trade union with some members on the site, but it hasn’t really been involved in these negotiations because Amazon won’t allow them to do so.

After all this, we had lost 10 hours of work, sitting in the canteen waiting for an answer. At the end of the day, the GM told us that they will give us an answer in a week’s time. However, they said they still couldn’t even be sure if this would be the final answer.

As of Friday, we are no longer fully striking. However, we have decided that we will not try and reach any targets, and instead try and make our job easier by working at a more relaxed pace.1

In another report, a worker in Coventry explained how they joined the current wave of wildcat strikes sweeping through Amazon warehouses in Britain:

We worked through the entire Covid-19 pandemic, including the lockdowns. We’ve been waiting for information about this pay rise since April with everyone expecting at least £2 extra per hour. However, management announced on Wednesday that we were only going to get a 50p rise per hour.

We only planned to go on strike two hours before it actually happened. We had seen the strikes at Tilbury and Rugeley fulfilment centres on TikTok during our break time, and it inspired us to strike. We watched those videos at 11am, and started spreading the idea of a walkout through word of mouth around the warehouse. By 1pm, we had over 300 people who walked out and stopped working. At the beginning, we had no help with the strikes from any trade unions. We organised it all ourselves. However, after we walked out, GMB made some contact with us about joining the union and giving us advice.

When we walked out again on Thursday, the GM (General Manager) came into the canteen area, where those of us refusing to work had congregated. The GM told us we had 30 minutes to come up with our reasoning for refusing to work and send someone over to discuss the strike with them. We refused to send only one person, as we all agreed that we wanted to go as one team.

We told the GM that we demand a better pay rise, asked them questions about our pay, and how they had come up with this 50p per hour rise. We were then told later that they would “take it away and try to get an answer.” After this, the managers said we wouldn’t get paid unless we returned to work. But everyone stayed, still refusing to go back to work.

On Friday morning, again about 100 associates walked out and protested outside. Our struggle is far from over. We have more collective action planned for the following days, as we keep fighting for a proper pay rise.2

As documented in the first testimony, on August 4th workers at Amazon’s Tilbury warehouse walked out.3 They had been offered a 35p pay increase, amounting to a 3% pay increase on the London region wage of £11.10 an hour: well below the Consumer Price Index of inflation, which is currently running at 10.1% and forecast to increase to 13% by October.

First hand accounts of the strike describe how the shock of a below-inflation pay offer prompted an unplanned work stoppage. Workers across every department downed tools, before assembling in the canteen for a fruitless meeting with management. In Rugeley, Amazon staff in another warehouse also stopped work, and before long video footage of the two strikes was circulating on Tik Tok. That footage inspired more walkouts the next day, and the action continued to build from there.

After a week of action, the antagonism between Amazon workers and bosses seems to have entered a quieter phase. Therefore, we presented some data on what just happened, some context on what it means, and some speculations about what might come next.

By combing through Twitter and news reporting, we were able to gather a small dataset describing what happened and when. It shows how an informal dispute that began in Tilbury and Rugeley blossomed the largest wildcat revolt against Amazon seen so far anywhere in the world (for now.)

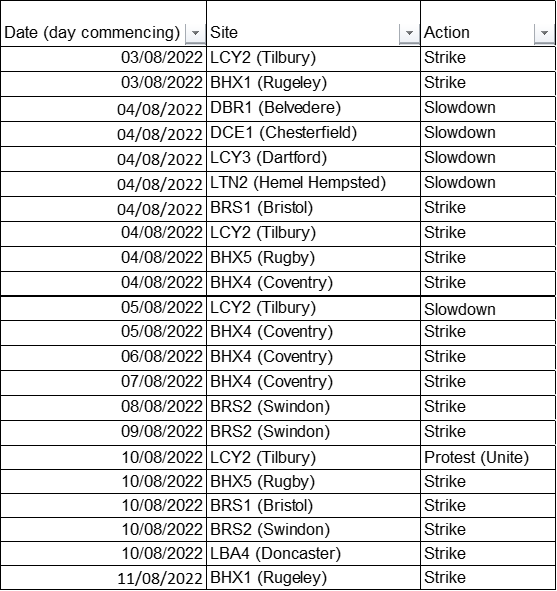

Between the 4th and the 11th of August we are aware of at least 22 different actions, ranging from strikes to slowdowns and protests, at 11 different workplaces. The map below visualises that action.

To understand the significance of these data points, it is necessary to dig into the class composition that prevails at Amazon in a little more detail.4

As you head out of the capital down the Thames Estuary towards the giant container port at Tilbury, Amazon becomes slowly more and more ubiquitous. First, you notice the prime vans, heading down the A13 into East London in ever-increasing numbers, then chartered buses, bringing in workers from Canning Town and West Ham towards LCY2 – a giant fulfilment centre (FC) that looms over a roundabout, within sight of the port.

LCY2 is home to 1,500 of the 70,000 workers employed by Amazon in Britain. There, they work in three shifts to unload lorries, store goods, retrieve goods, package them for distribution, and sort them ready for shipping. The workforce is broken up into five isolated units: receivers, preppers, stowers, pickers and deliverers, and watched over by roaming leaders and problem solvers. The technical composition of Amazon warehouses have developed rapidly in the last few years: workers now work closely with Kiva industrial robots, which shuffle mobile shelving units in an unlit compound in the centre of the facility. The robots manoeuvre these shelves to stowing and picking stations, where workers are prompted to load and unload items by an AI system which instructs them through coloured lights. As the range of inquiries published by NFB demonstrates, the work is characterised by high levels of surveillance and intensive productivity management.5

This setup is much the same at the other FCs across Britain. Amazon’s logistical system, however, doesn’t just consist of endless massive sheds. Other workplaces like sort centres and delivery hubs provide a base to the massive fleet of Flex drivers who work for Amazon’s last-mile delivery platform. Amazon is also investing in the specialist infrastructure required to run its Amazon fresh grocery service, as well as other functions such as Amazon Web Services. The FCs are just one point in this expansive network – albeit a very important one.

Amazon has never before seen wildcat strikes like this. There have been six wildcat actions recorded at FCs across the globe before this wave: in Poznan (Poland, 2015); Lille (France, 2018); Minnesota (US, 2019); New York (US, 2020) and Chicago (US, 2020 and 2021).6 None of these spread between FCs, and all appear to have been characterised by more limited participation. None have ever spread internationally before, either – but now, these wildcats seem to be doing just that. On August 16th, Inland Empire Amazon Workers United led a walkout at KSBD in San Bernardino South California over wages and workplace temperatures, and in Turkey up to 600 workers are also reported to have walked out of a warehouse in Kocaeli in the face of 79.6% inflation. Official action supported by trade unions also seems to be continuing to grow, with the Amazon Labour Union in the US applying for another union recognition election at the ALB1 FC, as well as yet another work stoppage led by Verdi workers at Bad Hersfeld, where strike action has been continuing on and off since 2013.

So it should not come as a surprise, then, that Amazon has not had an immediate playbook to call upon in response to these strikes. The company has extensive experience in beating back trade union organising efforts, but that is a markedly different scenario. As a worker noted in an account of the strike, their General Manager was ‘almost silent’, ‘not knowing what to say to us.’7

In Britain, the history of trade union attempts to organise Amazon workers is a history of disastrous failure. In 2001, the Graphical, Paper and Media Union (GPMU, now merged into Unite) set out to organise workers at Amazon’s first British FC, which had opened in Ridgmont near Milton Keynes three years earlier in 1998. Situated in an area of high unemployment near the M1, the site was a prime candidate for the new logistics industry. At the time, Amazon employed about 500 workers there, and over the course of an organising drive 100 of those joined the GPMU.

However, despite this apparent progress, Amazon had a game plan. They combined victimisation of trade unionists and captive anti-union meetings with a series of concessions, including a 10% pay rise. Amazon then initiated a statutory union recognition ballot, with the apparent goal of smashing the union at the FC. Gregor Gall, writing a few years afterwards, described what happened next:

At the time of the ballot, the GPMU received 23 union resignation letters from workers, on Amazon-headed paper, 10 of which were not from union members. During the ballot, a GPMU official reported he had seen ‘pre-printed ‘no’ ballot papers and the staff were kitted out with T-shirts telling the union to get back in the history books’. The result of the ballot was ‘conclusive’: of the 500 staff, 90% voted with 80% voting against union recognition, 15% for and 5% spoiling their papers. The GPMU received less votes than it had members.8

For a decade after that traumatic defeat, trade unions stayed away, and workers’ pay began to fall consistently in real terms. Only in 2013 did GMB relaunch an Amazon campaign, which has relied mostly on public pressure on the employer, leveraged through demonstrations, legal cases, petitions, press interventions, and stunts. There has been little tangible evidence of significant worker recruitment or action. Two other unions, Unite and the BFAWU, have also shown some intent to organise Amazon workers, although with similarly little to show for it. Whereas Verdi in Germany, the CGT in France, and the Amazon Labour Union in the US have all beaten Amazon’s union-busting to one degree or another, the same cannot be said for Britain’s trade union movement.

Amazon is expanding its British footprint. The company added 25,000 staff in 2021, and the trend seems to be continuing. Alongside this expansion in the workforce, Amazon is also ploughing money into fixed capital. Right now, a 1.5 million square foot facility is being built in Wynard, just north of Middlesbrough. It’s due for completion on the 30th of September. At almost triple the size of LCY2, it could house almost 4,500 workers under one roof if it operates as a sortable goods FC, and will even dwarf the massive EDI4 (Dunfermline, 1 million sq ft.) But it’s not alone - in 2021, Amazon opened facility after facility with over 500,000 sq ft: from BRS2 (Swindon); to NCL1 (Gateshead); LCY3 (Dartford); BHX7 (Hinckley); and EUK1 (Peterborough). As Kim Moody argues, this reconcentration of labour and capital is coming to define the ‘new terrain’ of capitalist production in the 21st century. These strikes demonstrate the potential for self-organised disputes to emerge on that terrain.9

However, there is no straight line between wildcat action and expanding worker power. The precedent of the platform economy shows us that self-organisation in new technical contexts is a proof of concept that workers can exert leverage over their bosses, rather than a guarantee that they will.

Unlike the platform economy, however, Amazon is profitable. The British business reported its profits soaring by 20% to £204 million in 2021. That would be sufficient to pay every worker in Britain an additional £2,900 per year from profits alone. However, the leverage created by even sustained strike action may struggle to compel this kind of distributional shift, as the cross-subsidisation of Amazon’s delivery service by other profitable segments of the business such as Amazon Web Services limits the financial pressure associated with a disruption of Amazon’s FCs. Wider conditions in the transport and storage industry are also not overwhelmingly positive. The labour market in the sector is relatively slack, with only 52,000 job vacancies, down from higher levels in 2021.

There are significant challenges ahead for Amazon workers. Now the initial wave of wildcat action appears to have died down, there is a lot of uncertainty about what comes next. Will they organise via a union, will they launch more unofficial action, or will Amazon regain the upper hand? It is difficult to speculate with any confidence. However, it seems likely that the answers to three questions will determine the course of the struggle to come:

-

First, will Amazon be capable of re-establishing control over the workforce? This could happen either through changes in workplace management or repressive action against self-organised workers. Either way, we can reasonably assume that in Amazon HQ there is a team dedicated to working out a strategy to achieve just this goal. In addition to this, we probably want to ask how Amazon will relate to the state whilst attempting to turn the tables on the strikers. Lizz Truss’ promise of more repressive union legislation shows that intensifying the system of management through which the country’s economic and political spheres are orientated to the interests of capital is a serious priority. Alongside the Police Crackdown Bill and Voter ID changes, a combined campaign of corporate-state repression.

-

Second, what relationship will emerge between the strikers and the Trade Unions? GMB have launched a pay claim for £15 an hour, and have attempted to recruit from the striking FCs. It seems likely they will follow up their claim with a ballot, if their membership has grown enough to make a minority strike feasible. Tension between Unite and GMB seems inevitable – it is understood that the former is the best organised union in Tilbury, but GMB claim to be the sole union with organising rights in the company. Any such conflict would have to be resolved by the TUC in line with their disputes principles. The company may also have something to say about which union it wants to deal with: in Poland, when given the choice between a radical union (the anarcho-syndicalist IP) and the historically-moderate Solidarnosc, Amazon willingly recognised the latter in an attempt to lock the former out of negotiations. The attempt only failed because Solidarnosc refused to negotiate in isolation, in solidarity with the excluded union.10 Clearly, Amazon understands that recognition can be used as part of a containment strategy. Given GMB’s recent ‘partnership’ deals with Uber and Deliveroo, there should be cause for concern amongst the trade union movement that yet another tranche of workers may be about to be deprived of their access to strong union representation by an emerging GMB strategy that consists of signing terrible deals without any mandate from the workforce concerned.

-

Third, how far will the workers leading these strikes seek to merge their immediate workplace demands with wider class demands as part of a political movement? We are in a febrile political moment: the purging of the socialist left from the Labour party and, indeed, the wider public sphere post-Corbyn had succeeded in provoking a long two years of demoralisation. But the cost of living crisis seems to be contributing to a change in the political temperature. Strike numbers are up, and many of the participants in those strikes clearly link the reasons behind their action to a wider set of political demands. Campaigns like Don’t Pay and Enough is Enough – whilst they are currently making relatively limited demands – have the potential to develop in interesting directions.

It is on this third question that political militants based outside of the FCs could really make an impact. By building connections with workers and creating supportive coalitions that can act to amplify their leverage, a small number of people on the ground can offer a vital connection point between any one workplace and the wider movement. Like the Gilets Jaunes who blockaded FCs in France and forced Amazon to concede a pay rise, supporters have an important role to play. In a period of relative political fragmentation, small initiatives like this can lay the groundwork for more impressive plans in the months to come.

Where next for union struggles?

In this chapter we have aimed to sketch out the broad outlines of trade unions in Britain. Examining the overall statistics of unions does not mean this translates into power in the workplace. However, anyone who starts organising in Britain has to relate to the existing union movement, whether directly or indirectly through the context it sets. It is therefore important to understand how the existing trade union movement (mostly through those unions that are part of the TUC) are skewed towards the public sector, with a membership that is increasingly older, female, and ethnically diverse. This is a shift from the image that many people of trade unionists as focused on manufacturing work with a white male membership.

The overall trends show a movement that is in secular decline. There have been moments of new organising or strikes in particular sectors, but the union movement is facing a demographic crisis. While independent unions have shown it is possible to reinvigorate union organising, as well as some parts of the existing union movement (as discussed above), there are still major challenges for building workplace power through trade unions.

It is also worth noting that during our investigation, we found that struggle in workplaces often happened without unions, or despite unions, and is therefore not captured in the official statistics. This analysis of the union movement therefore provides one set of insights into class struggle in the workplace, but certainly should not be taken as the full picture.

At the time of writing, union struggles during the hot strike summer have reached a rare peak. Hundreds of thousands of workers have taken strike action this summer, with discussions of future strike actions across many unions. There is also likely to be further changes to regulation of trade unions in Britain, including measures to try and prevent or reduce the effectiveness of strike action. The next few months could therefore be monumentally important in not just defending trade union rights and winning major disputes, but also for transforming the relationship between trade unions and the working-class.

-

For the full report, see: An anonymous Amazon worker (5 August 2022) Wildcat strike at Amazon, Notes from Below. ↩

-

For the full report, see: An anonymous Amazon worker in Coventry (7 August 2022) How the Amazon wildcat spread, Notes from Below. ↩

-

An expanded version of this section was first published in: Cant, C. (22 August 2022), ‘Mapping the Amazon Strikes’, Notes from Below. ↩

-

For more on how we see class composition, see the section ‘What is Class Composition’ in our Introduction to the Class Composition Project. ↩

-

You can see our full range of articles published on this topic here. ↩

-

Schulten, J. and Boewe, J. The Long Struggle of the Amazon Employees. (Brussels: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung, 2019). ↩

-

An anonymous Amazon worker (2022) ‘Wildcat strike at Amazon’. ↩

-

Gall, G. (21 January 2004) ‘Union Busting at Amazon.com in Britain’, Indymedia UK. ↩

-

Moody, K. On New Terrain: How Capital is Reshaping the Battleground of Class War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2017). ↩

-

Schulten and Boewe. The Long Struggle of the Amazon Employees (2019). ↩

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Retail Sector

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023