Mapping the Amazon Strikes

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

August 22, 2022

Featured in Hot Strike Summer: View from the Picket Line (#15)

New data on the wildcat action at Amazon

inquiry

Mapping the Amazon Strikes

by

Callum Cant

/

Aug. 22, 2022

in

Hot Strike Summer: View from the Picket Line

(#15)

New data on the wildcat action at Amazon

On August 4th, workers at Amazon’s Tilbury warehouse walked out. They had been offered a 35p pay increase, amounting to a 3% pay increase on the London region wage of £11.10 an hour: well below the Consumer Price Index of inflation, which is currently running at 10.1% and forecast to increase to 13% by October.

First hand accounts of the strike describe how the shock of a below-inflation pay offer prompted an unplanned work stoppage. Workers across every department downed tools, before assembling in the canteen for a fruitless meeting with management. In Rugeley, Amazon staff in another warehouse also stopped work, and before long video footage of the two strikes was circulating on Tik Tok. That footage inspired more walkouts the next day, and the action continued to build from there.

After a week of action, the antagonism between Amazon workers and bosses seems to have entered a quieter phase. So, this article presents some data on what just happened, some context on what it means, and some speculations about what might come next.

By combing through Twitter and news reporting, we were able to gather a small dataset describing what happened and when. It shows how an informal dispute that began in Tilbury and Rugeley blossomed the largest wildcat revolt against Amazon seen so far anywhere in the world (for now.)

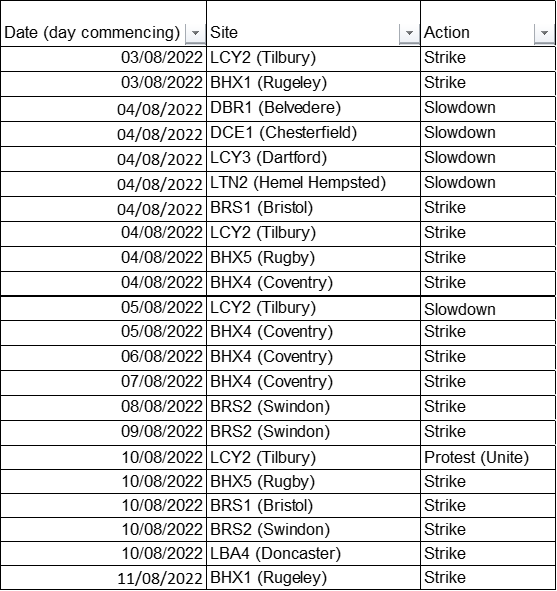

Between the 4th and the 11th of August we are aware of at least 22 different actions, ranging from strikes to slowdowns and protests, at 11 different workplaces. The map below visualises that action. You may need to zoom in to see each individual workplace which has taken action in areas where lots of workplaces are in close proximity, such as around East London.

Here is the same data in a table:

To understand the significance of these data points, it is necessary to dig into the class composition that prevails at Amazon in a little more detail. 1

The logistical hinterland

As you head out of the capital down the Thames Estuary towards the giant container port at Tilbury, Amazon becomes slowly more and more ubiquitous. First, you notice the prime vans, heading down the A13 into East London in ever-increasing numbers, then chartered buses, bringing in workers from Canning Town and West Ham towards LCY2 – a giant fulfilment centre (FC) that looms over a roundabout, within sight of the port.

LCY2 is home to 1,500 of the 70,000 workers employed by Amazon in the UK. There, they work in three shifts to unload lorries, store goods, retrieve goods, package them for distribution, and sort them ready for shipping. The workforce is broken up into five isolated units: receivers, preppers, stowers, pickers and deliverers, and watched over by roaming leaders and problem solvers. The technical composition of Amazon warehouses have developed rapidly in the last few years: workers now work closely with Kiva industrial robots, which shuffle mobile shelving units in an unlit compound in the centre of the facility. The robots manouvre these shelves to stowing and picking stations, where workers are prompted to load and unload items by an AI system which instructs them through coloured lights. As the range of inquiries published by NFB demonstrates, the work is characterised by high levels of surveillance and intensive productivity management.2

This setup is much the same at the other FCs across the UK. Amazon’s logistical system, however, doesn’t just consist of endless massive sheds. Other workplaces like sort centres and delivery hubs provide a base to the massive fleet of Flex drivers who work for Amazon’s last-mile delivery platform. Amazon is also investing in the specialist infrastructure required to run its Amazon fresh grocery service, as well as other functions such as Amazon Web Services. The FCs are just one point in this expansive network – albeit a very important one.

Unprecedented action

Amazon has never before seen wildcat strikes like this. There have been six wildcat actions recorded at FCs across the globe before this wave: in Poznan (Poland, 2015); Lille (France, 2018); Minnesota (US, 2019); New York (US, 2020) and Chicago (US, 2020 and 2021). None of these spread between FCs, and all appear to have been characterised by more limited participation. None have ever spread internationally before, either – but now, these wildcats seem to be doing just that. On August 16th, Inland Empire Amazon Workers United led a walkout at KSBD in San Bernardino South California over wages and workplace temperatures, and in Turkey up to 600 workers are also reported to have walked out of a warehouse in Kocaeli in the face of 79.6% inflation. Official action supported by trade unions also seems to be continuing to grow, with the Amazon Labour Union in the US applying for another union recognition election at the ALB1 FC, as well as yet another work stoppage led by Verdi workers at Bad Hersfeld, where strike action has been continuing on and off since 2013.

So it should not come as a surprise, then, that Amazon has not had an immediate playbook to call upon in response to these strikes. The company has extensive experience in beating back trade union organising efforts, but that is a markedly different scenario. As a worker noted in an account of the strike, their General Manager was ‘almost silent’, ‘not knowing what to say to us.’

In the UK, the history of trade union attempts to organise Amazon workers in the UK is a history of disastrous failure. In 2001, the Graphical, Paper and Media Union (GPMU, now merged into Unite) set out to organise workers at Amazon’s first UK FC, which had opened in Ridgmont near Milton Keynes three years earlier in 1998. Situated in an area of high unemployment near the M1, the site was a prime candidate for the new logistics industry. At the time, Amazon employed about 500 workers there, and over the course of an organising drive 100 of those joined the GPMU.

However, despite this apparent progress, Amazon had a game plan. They combined victimisation of trade unionists and captive anti-union meetings with a series of concessions, including a 10% pay rise. Amazon then initiated a statutory union recognition ballot, with the apparent goal of smashing the union at the FC. Gregor Gall, writing a few years afterwards, described what happened next:

“At the time of the ballot, the GPMU received 23 union resignation letters from workers, on Amazon-headed paper, 10 of which were not from union members. During the ballot, a GPMU official reported he had seen ‘pre-printed ‘no’ ballot papers and the staff were kitted out with T-shirts telling the union to get back in the history books’. The result of the ballot was ‘conclusive’: of the 500 staff, 90% voted with 80% voting against union recognition, 15% for and 5% spoiling their papers. The GPMU received less votes than it had members.”

For a decade after that traumatic defeat, trade unions stayed away, and workers’ pay began to fall consistently in real terms. Only in 2013 did GMB relaunch an Amazon campaign, which has relied mostly on public pressure on the employer, leveraged through demonstrations, legal cases, petitions, press interventions, and stunts. There has been little tangible evidence of significant worker recruitment or action. Two other unions, Unite and the BFAWU, have also shown some intent to organise Amazon workers, although with similarly little to show for it. Whereas Verdi in Germany, the CGT in France, and the Amazon Labour Union in the US have all beaten Amazon’s union-busting to one degree or another, the same cannot be said for Britain’s trade union movement.

What happens next?

Amazon is expanding its UK footprint. The company added 25,000 staff in 2021, and the trend seems to be continuing. Alongside this expansion in the workforce, Amazon is also ploughing money into fixed capital. Right now, a 1.5 million square foot facility is being built in Wynard, just north of Middlesbrough. It’s due for completion on the 30th of September. At almost triple the size of LCY2, it could house almost 4,500 workers under one roof if it operates as a sortable goods FC, and will even dwarf the massive EDI4 (Dunfermline, 1 million sq ft.) But it’s not alone - in 2021, Amazon opened facility after facility with over 500,000 sq ft: from BRS2 (Swindon); to NCL1 (Gateshead); LCY3 (Dartford); BHX7 (Hinckley); and EUK1 (Peterborough). As Kim Moody argues, this reconcentration of labour and capital is coming to define the ‘new terrain’ of capitalist production in the 21st century. These strikes demonstrate the potential for self-organised disputes to emerge on that terrain.

However, there is no straight line between wildcat action and expanding worker power. The precedent of the platform economy shows us that self-organisation in new technical contexts is a proof of concept that workers can exert leverage over their bosses, rather than a guarantee that they will.

Unlike the platform economy, however, Amazon is profitable. The UK business reported its profits soaring by 20% to £204 million in 2021. That would be sufficient to pay every UK worker an additional £2900 per annum from profits alone. However, the leverage created by even sustained strike action may struggle to compel this kind of distributional shift, as the cross-subsidisation of Amazon’s delivery service by other profitable segments of the business such as Amazon Web Services limits the financial pressure associated with a disruption of Amazon’s FCs.

There are significant challenges ahead for Amazon workers. Now the initial wave of wildcat action appears to have died down, there is a lot of uncertainty about what comes next. Will they organise via a union, will they launch more unofficial action, or will Amazon regain the upper hand? It is difficult to speculate with any confidence. However, it seems likely that the answers to three questions will determine the course of the struggle to come:

First, will Amazon be capable of re-establishing control over the workforce? This could happen either through changes in workplace management or repressive action against self-organised workers. Either way, we can reasonably assume that in Amazon HQ there is a team dedicated to working out a strategy to achieve just this goal. In addition to this, we probably want to ask how Amazon will relate to the state whilst attempting to turn the tables on the strikers. Lizz Truss’ promise of more repressive union legislation shows that intensifying the system of management through which the country’s economic and political spheres are orientated to the interests of capital is a serious priority. Alongside the Police Crackdown Bill and Voter ID changes, the outline of a combined campaign of corporate-state repression is becoming increasingly clear.

Second, what relationship will emerge between the strikers and the Trade Unions? GMB have launched a pay claim for £15 an hour, and have attempted to recruit from the striking FCs. It seems likely they will follow up their claim with a ballot, if their membership has grown enough to make a minority strike feasible. Tension between Unite and GMB seems inevitable – it is understood that the former is the best organised union in Tilbury, but GMB claim to be the sole union with organising rights in the company. Any such conflict would have to be resolved by the TUC in line with their disputes principles. The company may also have something to say about which union it wants to deal with: in Poland, when given the choice between a radical union (the anarcho-syndicalist IP) and the historically-moderate Solidarnosc, Amazon willingly recognised the latter in an attempt to lock the former out of negotiations. The attempt only failed because Solidarnosc refused to negotiate in isolation, in solidarity with the excluded union. Clearly, Amazon understands that recognition can be used as part of a containment strategy. Given GMB’s recent ‘partnership’ deals with Uber and Deliveroo, there should be cause for concern amongst the trade union movement that yet another tranche of workers may be about to be deprived of their access to strong union representation by an emerging GMB strategy that consists of signing terrible deals without any mandate from the workforce concerned.

Third, how far will the workers leading these strikes seek to merge their immediate workplace demands with wider class demands as part of a political movement? We are in a febrile political moment: the purging of the socialist left from the Labour party and, indeed, the wider public sphere post-Corbyn had succeeded in provoking a long two years of demoralisation. But the cost of living crisis seems to be contributing to a change in the political temperature. Strike numbers are up, and many of the participants in those strikes clearly link the reasons behind their action to a wider set of political demands. Campaigns Like Don’t Pay and Enough is Enough – whilst they are currently making relatively limited demands – have the potential to develop in interesting directions.

It is on this third question that political militants based outside of the FCs could really make an impact. By building connections with workers and creating supportive coalitions that can act to amplify their leverage, a small number of people on the ground can offer a vital connection point between any one workplace and the wider movement. Like the Gilets Jaunes who blockaded FCs in France and forced Amazon to concede a pay rise, supporters have an important role to play. In a period of relative political fragmentation, small initiatives like this can lay the groundwork for more impressive plans in the months to come.

-

For more on how on how we see class composition, see The Workers’ Inquiry and Social Composition ↩

-

To see the full range of articles published on this topic, click here. ↩

author

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Wildcat strike at Amazon

by

An anonymous Amazon worker

/

Aug. 5, 2022