The Education Sector

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

March 21, 2023

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

Written by education sector workers involved in the Class Composition Project

inquiry

The Education Sector

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023

in

The Class Composition Project

(#16)

Written by education sector workers involved in the Class Composition Project

The role and scope of education

The function of education under capitalism is to produce the next generation of workers (and in particular cases, bosses), as well as managing surplus populations until they are of an ability to join the working population. In part, this is about training and equipping new workers, while also preparing and disciplining people to become workers. This can both be explicit with the kinds of activities and the way they are completed, as well as in a wider ideological sense. The privatisation of education over the last fifty years has accelerated this.

The role of education in class composition is therefore twofold. First, as workplaces that are spread across every city, town, and village of the country. There are approximately 2,983,000 workers in the education sector, accounting for around 8% of the overall workforce. The ways in which this work is organised, the conditions, and struggles of workers is significant. Second, education plays an important role in the class composition of future workers. It shapes the expectations of work, providing students with resources to enter the workforce, and even with experiences of struggle to be brought to work.

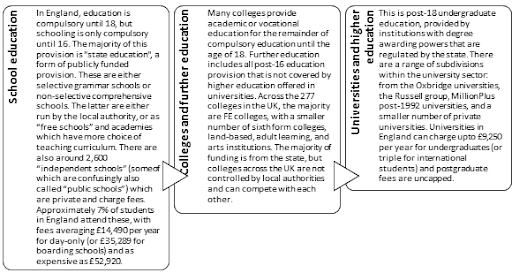

Within the sector, education can be broadly divided into three parts. It is also worth noting that education is devolved across Britain:

The education group process

The education group met throughout the class composition project. Across the entire education sector, there were 98 responses to the class composition survey - which almost makes percentages very easy to work out. We collectively analysed the responses to the survey to get a picture of the broader trends and patterns in work and struggle across the education sector, and we also conducted a series of long-form interviews with different education workers, to further clarify the experience of working and organising in education over the last year. The initial findings (adapted here) were published during the project.

Trying to engage education workers across higher, secondary and primary education has been a primary concern - drawing insights from each into comparison, and so hoping to avoid the far too common separation of workers across a single industry, with the aim of recognising shared potentials for political intervention and mobilisation.

Given the decade-long cycle of national demonstrations and strikes within higher and further education, the repeated national confrontations between teachers unions and the government, as well as the ongoing localised disputes unfolding in schools and higher education all around the country, we have begun to situate these education struggles alongside one another, and to see how they map onto disputes and shifts in work in the other industries being explored in the Class Composition project.

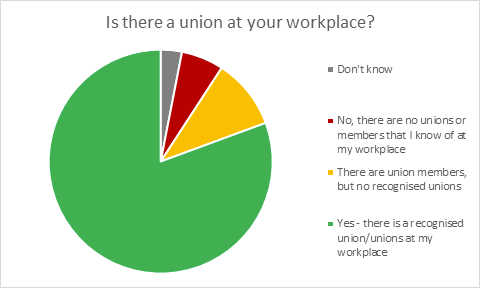

While unions play a role across education (see the pie chart of responses to whether there is a union in the workplace), we recognised the risk of limiting ourselves to analysing the immediate conditions of nation-wide disputes, such as around pensions and UCU’s ‘four fights’ campaign, however vital they are. Rather, we need to develop a platform for drawing together the lessons of the many localised campaigns happening within and outside the formal union apparatus. Central to this project is therefore to also focus our attention towards those struggles which are neither well represented nor widely understood.

The education sector is undergoing major shifts in its composition, from the nature of employment for workers in schools and post-16 education, to the massification of student bodies within universities. We see our inquiry not merely as a sociological study of current trends in workplace disputes, but as a tool for militant intervention into these struggles.

Later in the project, we held a day-long session with education workers to collectively discuss the issues that had come up in the surveys and interviews. The discussions on the day were transcribed and became the basis for this section.

Initial findings

From what we have found so far, there are a number of themes most commonly mentioned, and that have given us a general direction for continuing our analysis. As with the initial finding for the class composition project, we have found the prevalence of deskilling in schools and colleges particularly prominent, such as with the increasingly common use of teaching assistants as substitute teachers for a minimal (or even no) extra rate. Our interviews and survey results have similarly pointed toward stark inter-generational dynamics shaping the nature of organising in education work, with different sets of investments, experiences and expectations creating divisions within the workforce. Many reported on the hostile environment in their workplace, particularly from an unresponsive manager tier, and that structural and overt bigotry continues to profoundly shape their experiences in education work. Deep-set issues of sexism and racism intensify difficulties in organising in these conditions. Worries over casualisation and intensified precarity of work were widely reported alongside a general sense of despair towards being able to combat these trends.

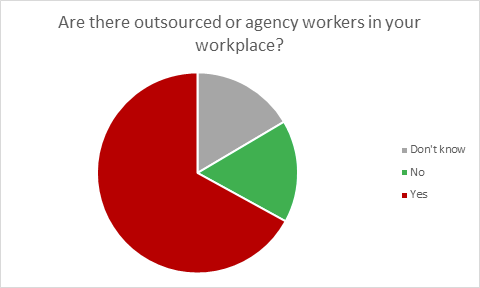

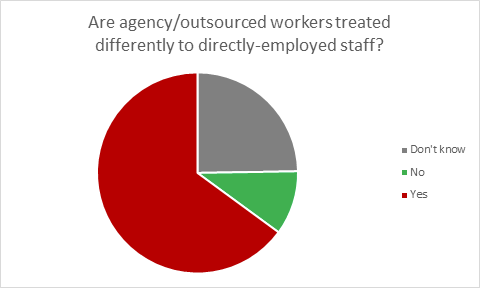

Across education, outsourcing of workers is a widespread issue. As the pie charts below highlight, there were many instances in which survey respondents had outsourced and/or agency workers in their workplace - and many of those outsourced workers were treated differently.

Despite high levels of unionisation, many respondents note issues with effective unionisation and concerns with the limits of formal organising in their workplaces. For example, several participants in interviews have pointed toward informal and inter-personal networks as more vital to their navigating of the Covid-19 crisis than the support they received from their unions. The structure of unions and the decision making processes over how struggles are led, won and ended, is an evident point of tension for many militants in the education sector, with the need for a renewed socialist rank and file perspective equally clear.

Part 1: School and College Education

Over the past forty years, the education system has been undergoing a series of longer term changes. As one teacher explained to us:

The neoliberal agenda in education, first from Thatcher and the Tories, then New Labour, involved a deep ideology about education. I was a teacher for thirty years and I can see very clearly the changes. Most took place between the 80s up until ten years ago. There was a whole new culture and it involved turning schools into academies and pushing out older teachers. In my school, this involved a new headteacher who bullied staff and was very disrespectful, trying to push teachers to take early retirement. By the time I left, 98% of the staff had gone. Then I was offered to come back and teach on contract. It’s not that they didn’t need people to teach, it was that we were expensive. It was an ideological attack, changing the school culture from one that is centred around children to one that is more focused around the marketization of education. It was about pushing out parents and not getting them too involved. It was about removing voices of dissent. A lot of the old teachers in my days were a lot more vocal and we were unionised.

This quote summarises many of the key changes that have unfolded in education. It also points to three important parts of how education has changed that will be covered in this section: the work of teaching, class composition in schools, and the composition of students.

The work of teaching

One of the key changes has been the creation of academies. These were introduced by Tony Blair’s New Labour government in 2000. 45% of state-funded schools have now become academies, the majority of them doing so in the last decade, with the government now aiming to pressure all schools into becoming academies by 2030. Academies have been through a series of changes since they were first introduced, but the main shift was to make state-funded schools independent from local authority control. Instead, they become self-governing charitable trusts - but can also gain support from other sponsors. This means they can change what is taught in schools and make choices about how to run the school.

As one teacher explained to us, this also meant trying to break existing worker organisation in schools:

In the multi-academy trust structure, they put new leadership into our school and you can tell they were put in to slap us around a bit. They didn’t like that teachers in our school have quite a lot of autonomy over what they teach or that we have extra frees in our timetable. They didn’t like that we do stuff that couldn’t be put into the spreadsheet and justified, like the wide variety of arts and music. They put more teaching load on our timetables, everything else got hollowed out of the school. There were all these brilliant things that got hacked away.

As can be seen from this description, the process of establishing academies was not only moving out of local authority control, but also changing the way teaching was delivered and the organisation of the work. As another teacher outlined:

Academy schools are run like a kind of business model. They are really harsh on behaviour, all kinds of sanctions. There is a really boring, abstract curriculum. They also discipline teachers with support plans.

Academisation can therefore be seen to have fragmented teacher practices, and therefore further atomising school workers from sector-wide norms. Whilst often picking and choosing from each other’s resources, each academy has their own curriculum, and their own school of ‘pedagogical thought’. Teachers who therefore don’t suit these styles are frequently pushed out under the auspices that they were ‘not a good fit’, usually being replaced by a NQT (newly qualified teacher) whom academies, whether correctly or not, see as more moldable to their own way of doing things.

As another teacher reflected, this has gone beyond just managerial strategies in the workplace:

The training has changed. They have a different model of teaching that they are primed with today. It’s a model that gets them ready to accept what they find when they get there. They no longer get more left-wing leaning philosophies and ideas in training, like the child-centred learning concepts that I went through when I was doing teacher training. There used to be a strong anti-racism element too. I was quite aware that education and schooling was a place where change was possible. Changing training is one part of the plan. It’s about preventing people from finding the energy, the space, or the time to focus on anything that may well encourage them or help them to challenge the status quo.

As will not come as any surprise to anyone who has worked as a teacher or knows someone who does, teaching workloads have greatly increased:

The job always leaks out of my paid work hours. Oh my god, absolutely, definitely. I try as much as possible to keep it at work. So that means that I end up coming home late quite often. And I end up doing work on the train, like marking papers or finishing a lesson. I do really try and make sure it’s not encroaching too much on my weekend. A lot of the other teachers will say that you have a very intense life during term time. I did not think you would have to work so hard as a teacher, I know a lot of people have been falling behind.

Workloads have not just risen for teachers - other school workers have also spoken of increasing and untenable workloads. One teaching assistant described the situation in their school, a newly opened academy, where they originally have five free periods a week in order to complete admin work. This slowly boiled down to four, then two, then one, before eventually reaching no admin periods a week - something that would be illegal if they were a teacher. This meant that they were working a full timetable a week in the classroom, leaving them no hours to do classroom preparation work, and little time afterschool to fulfil their many other admin duties. They described how this situation negatively affected both staff and students. Even when beneficial to no-one - with regards to the students education, the school’s results, and the workers’ conditions - an industrial logic, in which quantity of labour-power expended is prioritised over quality of work, can be seen to have taken a deep root in the education sector in this regard.

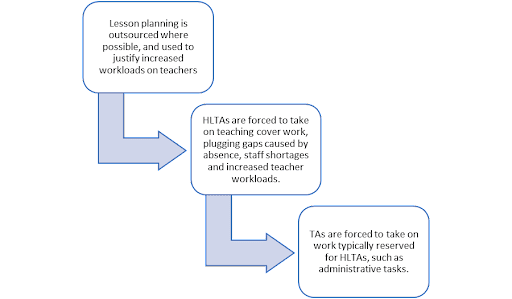

Increasing workloads and the deskilling of job roles also appeared to reinforce each other. A number of teachers spoke of curriculums and lesson plans being purchased (often from academy chains) by the school, and then used as an excuse to cut teacher PPA (planning, preparation and assessment) time. HLTAs spoke of being requested to act as cover teachers, even providing long-term cover, with little-to-no remuneration and no additional planning and preparation time scheduled onto their timetables. Further down the line, TAs discussed how they were slowly accumulating more duties that would traditionally be performed by a HLTA, but were instead being spread out between TAs. In fact, increasingly even TAs are being asked to do teaching work far beyond their payscale. As two anonymous TAs put it:

Where [teaching assistants’] choice of job-description becomes somewhat political, is on the question of covering lessons, and ‘teaching’ without ‘QTS’ (qualified teaching status). Increasingly TAs, especially those on agency contracts, are asked to do the work of teachers, in all but name and pay.1

It is here that we can see a chain, in which deskilling of job roles leads to such work being broken up and added on to others further down the payscale in their workplace. TAs spoke of some informal resistance against such conditions in their workplaces - such as teams of TAs simply ignoring new admin assignments, or frequently skipping a number of timetabled lessons due to high workloads. Whilst there are national campaigns on workload from the NEU (National Education Union), resistance to workloads and deskilling in actuality appears relatively thin on the ground. In the case of teachers, this is perhaps due to the high level of pressure to complete curriculums and achieve certain results in order to remain in good standing with their employers.

Composition of teachers

The change in approach to training has also involved formal shifts in the training of teachers. This means that there are many more NQTs (Newly Qualified Teachers) being brought in to teach in schools:

Where possible, they will hire a good NQT. They are keen and cheap. They might be hired for a limited time, but they don’t even need to put an NQT on a one-year contract. If they fail the training, they can just get rid of them anyway. Then they just keep hiring teachers on one-year contracts. It’s casualisation right? Because it’s getting rid of older, expensive teachers and bringing in cheaper non-union teachers.

One immediate change is that in many schools the average age of teachers has dropped, with the majority of teachers now being under the age of 39. One reason for this pursued demographic shift by the management of schools was explained to us by a teacher:

If you’re in your 20s and your new manager says: “do more work”, you don’t have responsibilities where you can kind of say “no”. You find this a lot in teaching, older staff will just go “fuck off. I’m not doing that.” Whereas a young teacher will say “Yes. Okay, fine, I’ll do it”, as they are trying to impress the new manager.

As these two quotes show, there is a changing composition of workers within teaching, with an increasing shift towards younger, less experienced teachers who are less likely to be union members. As previously discussed, there has also been a growth of teaching assistants, or HLTAs, being made to teach classes as cover during Covid-19. This is deskilling teaching. It also undermines the previously strong levels of unionisation, even if union recognition and collective bargaining agreements might still be in place. Even in workplaces that have high levels of NQT unionisation, high turnover presents difficulties for workers to find a footing and get active in their branches. This can be seen to create a cycle where the go-to resistance to high workloads and bullying SLT (senior leadership teams), particularly for NQTs, becomes resignation, either to move to another school or to drop out of the sector entirely. This turnover is also especially common in TA populations, who now make up 30% of the state-funded sector workforce. One respondent told us how seven TAs, in a team that totalled only eight TAs in total, had resigned from their workplace in the last nine months - with half of these resignations happening in one half-term alone. Turnover amongst TA populations is further aggravated for those who are outsourced. As two TAs have reported:

The short-term nature of most agency TA contracts - and the attendant idea that they are a ‘stepping stone’ towards either in-house job or teacher training - means it’s very hard to come across people who have spent long enough on these contracts to seriously organise.2

Relationship between workers and trade unions

The main teachers union is the NEU (National Education Union) formed as a merger of the NUT (National Union of Teachers) and the ATL (Association of Teachers and Lecturers). There is also NASUWT (itself a merger of the National Association of Schoolmasters and Union of Women Teachers), and a series of smaller organisations. As one unionised teacher explained:

So on the top level, at districts or branches, whatever you want to call it, quite a lot of the casework is to do with teachers being put on support plans or older teachers trying to get redundancy settlements. There’s a lot of that. So like a lot of day to day casework for union officers is helping people get settlements or having people keep their jobs. But normally, by that point of the year, the bullying tactics are so much that people don’t really want to fight. Because it’s a process, it’s hard to win, really.

Education is the most highly unionised sector in Britain, with almost 50% of education sector workers being union members.3 Whilst most respondents who worked in schools claimed membership of a union (most significantly, NEU), only a few said they were currently active. These members who claimed to be active were almost exclusively workplace or branch reps. A number of respondents who claimed to wish to be, but are not currently, active, stated they hadn’t become active because they didn’t have time to be a rep. Others claimed their rep hadn’t called a meeting in the past year, and hence they hadn’t found a natural entry point to get involved. This indicates a situation in which the top down nature of mainstream education unions excludes the participation of those not in official positions. As one member of the education working group, who worked in a school and was a union member, put it:

I joined the union on my first day on the job. I was keen to get involved, and told my rep early on a number of times that I was up to help with anything. However, it took 6 months for me to even be added to my local branch chat (which was on the same chat software we used for the school, meaning management had access to all discussions that occurred there…). The whole time I worked at the school, we had one local meeting, in which general grievances were brought up and the only solution was the rep agreeing to have a meeting with the headteacher about them. Whilst there were a number of discussions between staff members throughout my time at the school about the need for strike action, there was no effort to collectivise our grievances at a union level, nor were there really opportunities to do so. There were monthly district level meetings open to all members, however these were poorly attended, mostly just by reps, and no decisions of any substance could be made there.

As they continued, this exclusion extended from the local right up to national union:

There was no advertisement by our local union over the indicative pay and workload ballots for teachers when they occurred last year, nor did the national union advertise indicative pay ballots for support staff. Of my support staff team, in which around half were union members, I was the only one to even receive the indicative ballot in my email - and I only did so because of persistent emailing to the national union office asking for my ballot. Despite a majority voting for strike action, due to low turnout, any potential strike action was ruled out for support staff over pay claims, and a paltry 1.75% pay rise was negotiated instead. This institutionalised exclusion of rank-and-file members from the union structures, despite NEU’s reputation on the left as an active and ‘militant’ union, created a culture which not only prevented collective action from occurring, but also put off militant members of my workforce from joining the union.

Perhaps this should come as unsurprising to us, following on from our discussion in the initial findings of our project, and our more general understanding of the contemporary trade union movement in Britain. Whilst also reporting this issue of top-down union directives, low-activity levels amongst the union base could also be understood through how education workers join the union in the first place. For many teachers and teaching assistants, who make up the bulk of the unionised workforce, the education unions are advertised as insurance policies, as the people who will help you in the case of a false accusation by a student or parent. Whilst many come to see the union as a place where workers can collectively tackle the issues that are rampant amongst the education sector, this pitch naturally encourages a passive membership.

Despite the union situation described here, collective action was still widely reported to us - although it often occurred outside of union structures, in a subterranean manner. A large number of respondents fed back to us that they undertook ways of resistance in the (both individual and collective) form of simply ignoring tasks they saw as pointless or too much, took extended and unscheduled breaks, went home early, called in sick frequently, and refused to cover the work of colleagues who were sick or had been made redundant. These actions were reported to us as having occurred mostly in workplaces without an active union membership - however, far from discouraging people from resistance, it simply pushed these forms of resistance outside of the union to different, even if limited, forms.

This is not to say that unions were disengaging in all examples - indeed there were a number of positive responses about local union engagement too in our survey, and we can see this in a number of local disputes from activated union memberships, with strikes fighting academisation, pension cuts and trade union victimisation.4 These examples are encouraging and require further analysis into how they came to be; however, it seems that unfortunately they did not represent the generalised situation.

Outsourcing

A final important trend in school workplaces is outsourcing. A number of key roles in schools have been outsourced in recent years, most notably caterers, cleaners and teaching assistants. These trends in outsourcing also don’t necessarily create the same conditions for each of these different roles. For instance, caterers and cleaners are often outsourced, and therefore technically are employed by an agency. However, these workers will usually work in the same school, with the same workers, year in year out, as opposed to being moved around. On the other hand, outsourced teaching assistants are often signed up to an agency, and move round different schools on a regular basis, used to plug gaps on an if and when basis. Similarly, outsourced teaching assistants will often be mixed into in-house teaching assistant workforces; however, outsourced caterers and cleaners are usually done entirely so within singular workforces. This creates different difficulties for both these sectors of the workforce: cleaners and caterers, who have been historically excluded from education unions, become even more separated from their coworkers via their technical employment by another company; whilst teaching assistants, although slightly less alienated from the mainstream education unions, find it difficult to gain a footing and make the necessary industrial alliances to take effective collective action due to their numerical and geographic isolation.5 There have been successful examples of outsourced workers taking action to fight their conditions, such as UVW members at Ark Globe Academy who took wildcat strike action over unfair wage deductions and working conditions.

However, an industrial unionism is necessary to truly unify these workforces and strengthen the struggles of all education workers, particularly as the roles of schools as providers of food and childcare have become highlighted by a society of intermittent pandemic lockdowns. This means that in potential future industrial action by teachers, schools could be kept open as centres of capitalist social reproduction if support staff, cleaners and caterers are not also on strike. This would severely minimise disruption caused by teachers striking. Therefore, the question posed by two outsourced teaching assistants, becomes incredibly important to answer:

The NEU and the ‘support staff’ unions can all, according to their websites, represent these cleaners. Why haven’t they?6

Not only must we ask why haven’t these unions put more effort into supporting the struggles of these workers, but we must start to think about how we can build industrial alliances, and through our own self-organisation, force these unions to take a unified industrial strategy.

Composition of students

Many academies have involved a focus – even pride for some chains – on strict discipline in schools. As one teacher, reflecting on her long career in teaching, explained:

I feel like education, particularly at primary school, should be the building blocks of life. It’s all about behaviour and learning life skills, as well as being academic with maths and English and everything else. And I just feel as if it’s total academia now, and it’s all totally about spreadsheets looking good.

This has important implications for the composition of students being taught in schools. The experience for students today is shifting as schools are becoming increasingly disciplinary focused. As one school worker told us:

This new academy opened up two years ago. It is very, very disciplinary. Students have to line up, no talking in the corridors, walk on the left, or get shouted at. They have a very, very strict behavioural policy. So at the end of last term, out of maybe 600 kids in school, 15 of them were in an isolation room, where they are separated from all other students and are not allowed to talk at all. Almost all the students who are regularly put through these horrible processes by the school are Black or South Asian.

One aspect of this has been the increase in exclusions as a disciplinary tool. No More Exclusions, is a grassroots abolitionist organisation that has been campaigning on the issue.7 As they explained, they oppose exclusions because they are:

having such an immense destructive outcome on children’s lives. This is a particular demographic of children, those with special educational needs, racialized groups, and with mental health and social-emotional issues. We’re finding that the number of children excluded has increased under the pandemic. It is totally out of hand and totally callous. There’s no excuse for the government to allow this to run rampant. It’s all part of their policy of rolling out zero tolerance policies in the academies and not wanting to address the real issues that pertain to the lives of the most vulnerable in our society. They are looking for easy solutions, but capitalising on the misery of our communities and children.

As education workers, we also observe the ways in which our students resist punitive systems within schools, and the working-class creativity that is used to counter the ways in which schools try to discipline them. One member of our group mentioned:

I see the ways in which students resist the totally bullshit disciplinary measures management and some teachers try to enforce. In my school we have a three strikes policy, in which on your third warning you automatically get a detention. I’ve seen many times students play this system, in which they continually disrupt classes to avoid having to do work, but spread out these actions amongst each other so that no one student meets this three-strike threshold. Whilst this may be slightly annoying sometimes, these acts of solidarity amongst students are in many ways encouraging, and it would be interesting to see how these attitudes will play out when they get older and join the workforce.

These punitive measures do not only affect students, but also change the dynamics for working in the school too. For example, one teacher explained that:

A school that has incredibly high rates of exclusion is a horrible school to work in as a teacher. Most teachers are in favour of exclusion or haven’t questioned it as a policy. It’s part of your training and part of the culture of the school you work in. I’ve always found that you have to toe that line, or you’re policed in the same way that you are told you have to police students. And they’re watching you to make sure that you carry out the roles that lead towards exclusion.

As spoken about here, exclusions, despite their detrimental effects to both students and workers, continue to be supported by many teachers as the default. Some education unions, such as NEU, have passed policy at national conferences in favour of a moratorium on exclusions, however this has seemingly been followed by very little action from the union as a whole. The majority of action pushing against exclusions therefore still comes from the bottom-up, via groups such as No More Exclusions that include a combination of education workers, students, parents and community supporters.

However, whilst there have been pushes from the ground level against these measures, many teachers default to supporting exclusions in favour of ‘behaviour management’ and ‘staff safety/wellbeing’ - including union members and teachers who would view themselves as ‘progressive’.8 This default support of exclusions and similar punitive elements of schooling could be seen as partially stemming from the technical composition of teaching work today: extreme pressure is put on teachers to complete syllabi no matter what; class sizes and high turnover prevent teachers from developing meaningful relationships with as many students; and training is often placed in the hands of academy federations who seek to install their own punitive pedagogy as gospel within NQTs. The struggle against exclusions, pushed forward by groups such as NME, could therefore act as a launching pad against all these other negative working conditions that currently affect teaching staff, and break down divides between students and education workers that have been built up through the use of authoritarian processes such as exclusion. Indeed, in an interview published by Angry Workers, an anonymous education worker at Pimlico Academy, citing a series of protests and strike action over racist and authoritarian behaviour policies, commented on the importance of student protests to challenge teachers’ blindspots to these issues, and mobilise them against them.9

It is also worth noting the observations by participants in the CCP of differences in attitudes between different staff with regards to this issue. Whilst it is certainly not the case that all teachers are supporters of exclusions and all support staff are opponents, as there are significant portions of both populations that have the opposite position, it was observed that support staff were generally more opposed to authoritarian measures in schooling. Indeed, one participant in our project recalled a series of resignations by TAs in their school over the introduction of an ‘internal pupil referral unit’, which aimed to isolate so-called ‘disruptive’ students from the rest of the student body for a fixed period, and install ‘proper school values’ in them through intense discipline and other punitive measures. Again, this could perhaps be seen as partially a result of the technical composition of their work, with support staff often working more closely, in smaller groups, and with students who are more likely to be vulnerable. However, trends also show these elements of the work for support staff changing, with issues such as increasing workloads, and a push for support staff to work with a wider number of students, coming up in the education section of our project. Therefore attitudes towards measures such as exclusions could well shift in a negative manner as a result of a failure for education workers to push back against these deteriorating conditions.

Overall, the growth of these authoritarian measures in schools has transformed the experience of schooling for students. For example, one teacher had spent time discussing the experience of school with her daughter:

She went through a really difficult time. She told me it was that kind of constant kind of pressure to perform, perform, perform. And she just felt emotionally in a place of siege. She wanted to be able to take on the pressure. She kept her head down, but she only I think just about got through it. But when the pandemic came, she just sobbed and sobbed. It was like pressure had been taken off. All the things she’s worked for, and now won’t be able to do the sit-down exam. It left her in a place just feeling quite angry and empty. She now just hates her school. She hates the school for what they’ve done to her. That’s how she feels. I feel like it’s really sad that a child who is very interested in learning, but that’s how she’s left school. Why? I don’t think my daughter is, you know, different from many other children. You know, education should be about the joys of learning. And that’s certainly not what it is now.

Against this backdrop, there have also been a wave of school student protests, particularly around Black Lives Matter and Palestine. There have also been protests against the use of algorithmic decision-making for exam results during the pandemic, and let us not forget the mass walkouts as part of the climate strike movement in 2019. There is a new moment of political composition of school students, something that has not been seen since the walkouts of the invasion of Iraq in 2003, that requires further inquiry (ideally by students themselves!) and serious consideration when assessing the contemporary class composition of the education sector in this country.10

Part 2: Higher Education

Universities play a different role in capitalist society than schools or colleges. Universities began as elite institutions that trained a layer of the ruling class, while also providing an important ideological function. After the 1960s, many more universities were established in Britain and the number of students began to increase. After 1992, many former polytechnics became universities, further increasing the number of institutions. The overall landscape of higher education has been shaped by government policy. First, Tony Blair’s Labour government set a target of 50% of young people going to university, which was met in 2017. Second, after the Blair government introduced tuition fees of £1,000 a year in 1998, they increased to £3,000 in 2004, then - despite widespread student protests - the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government raised the undergraduate fee cap to £9,000 per year. Postgraduate fees are uncapped. While these changes affected England, due to devolution, there are different arrangements in Scotland, Wales, and the North of Ireland.

Across these changes, the universities sector has become increasingly marketised, with the introduction of competition, league tables, and rankings for research and teaching. There are 214 universities and higher education institutions, with a student population of 2.75 million - the overwhelming majority at universities in England. There are an estimated 600,000 international students, who can pay substantially higher fees. Universities employ 225,000 members of academic staff - with many more workers in other roles across the university. The work of academic staff is broadly divided into three parts: research, teaching, and administration. However, universities rely on a range of other roles, from cleaning, catering, security, groundskeeping, IT, professional services, and so on.

Work in higher education

As with other parts of the education system in the UK, universities have gone through a series of major changes. A lecturer explained to us:

Higher education is a sector that a lot of people go into believing that it’s a prestigious job. It’s traditionally been made up of people from middle class backgrounds. But also, people have approached it somewhere they can carry out work that’s intellectually fulfilling. There’s the teaching side to the job and there’ll be an opportunity to do research and produce knowledge.

This involvement in the job means that for many workers, being an academic is part of their identity:

I think people are very individualised, they imagine their career path as an individual journey. Our university would be kind of quite generally left wing. Or liberal maybe might be a better word, but they have abstract ideas about social progress and social justice. There’s no sense of needing to act together collectively to make that happen. You know, sometimes I wonder if people are just playing out their identities of being leftist rather than actually, you know, engaging with some of their co-workers to try and try and build a majority to change things. Sometimes I think I’m being a bit harsh.

This is something that has come to the fore through the regular strikes in higher education:

So I think this is the contradiction that we see with industrial action, right? Higher education has been one of the most strike prone sectors of the British economy over the last 10 years. The union has not won a single thing out of those strikes, which is interesting in a way. Almost every year there has been a period of industrial action. And we know the bit of industrial action that would be the lever through which we could win. It’s the bit that highlights what the job is really about. If you don’t mark the papers and give the grades, that’s where our industrial power is in the university. But so many academics are like, ‘oh, we have a duty to our students.’ Sure, but, you know, it means that you don’t ever take action like that, we’re going to keep having conditions get worse and worse. I’ve had colleagues at work saying, ‘I’m going to rearrange this, my teaching, because I really care about my students.’ There is this constant, low level scabbing that academics do. I care about my students, I really care about them, and that’s why I want to take action.

Despite these strikes, the changes to higher education are continuing:

At least in the last 20 years, it has become increasingly privatised, the relationship of higher education to the state has fallen away, and higher education has become increasingly dependent on recruitment for its economic sustainability. And this has had all kinds of consequences on the structure of work and universities. One of the major issues I’ve experienced in my time in higher education, which started in 2010, as a student to present, has been the growing spread of casualisation within the culture of work and higher education. It takes the form of insecure, temporary contracts for an increasing number of core teaching and research work that goes on in universities, not explicitly but also in professional services. Increasing areas of work are underpinned by temporary contracts, and the turnover of staff is quite high. The conditions of work are, you know, increasingly dysfunctional. The nature of casualisation itself is incredibly composite. There’s many different types of casualization. And this reflects different types of work.

Another academic worker continued:

I think one of the things that’s striking in higher education, is that if it’s not the majority of the workforce isn’t yet casualised, it is certainly moving in that direction. I think often the way in which the kind of discussion around it happens in the union is sort of the other way around. They still talk about these as non-traditional contracts. There’s obviously something contradictory about calling the majority of contracts non traditional. But I think that points to something that’s happening in the sector more generally. The level of disorganisation is actually massive and many of the structures, both professional and organisational, continue to operate as if it was a peripheral kind of issue. All you have to do is look at the weakness of the casual member’s campaign in the union. First of all, it’s a separate campaign, and it’s kind of an add on. It’s made worse by the separation between academic and non academic staff in universities, which I think hides the depth of the problem.

The Covid-19 pandemic had a significant impact on universities, which were mostly closed for the start of the lockdown. Many of the interviews discussed the isolation and disconnection that the pandemic caused, building upon these longer trends within the sector. However, for some academic workers, this also offered benefits:

I haven’t been on campus since the first lockdown. I’ve done all of my work, all of my teaching, and all of my meetings and everything is all entirely online. There are obviously limits to that. I’m not able to have the kind of water-cooler chats with colleagues that, you know, might have previously contributed towards building the union. I think there are some strengths to being online and I would quite like to keep that going forward.

Another explained that:

University management’s response to Covid-19, has been broadly similar to how the scientists and bureaucrats reacted to the Chernobyl crisis in the Soviet Union. When they’re presented with the facts, they just don’t want to know, because we’ve got to carry on with business as normal. We’ve got to get the bums in the seats, get the student halls, jam packed full. And to hell with all of the health and safety issues or worker’s lives.

There was often a disconnect between management and academic workers in the responses to the survey and the interviews. This connects with the individualisation and competition discussed earlier. For some of the workers we interviewed, this went far beyond passive competition between colleagues or attempts to be managed. For example:

We’re working in a toxic environment. That means we’re all thinking that if we stand up, we’ll be picked on right? They try to get people to work really hard. In conditions like this there’s a lot of bullying going on, and that bullying tends to play out in groups. Now within groups there are also people who get opportunities and those who get the time-consuming jobs. So there’s an in and an out group. Middle management are overwhelmingly white and male and kind of recognise people like them. They have their favourites amongst the staff. It plays out on racialised and gendered lines. I think a lot of the discourse on racism in academia doesn’t take into account the intersection between bullying practices and institutions. You can’t separate the racism from the way bullying is encouraged by the overall system of labour management. And most managers are just copying the one above them.

It is important to note that universities would not function without a range of other workers that support and run the organisation. The relationships between academic and non-academic workers could be a source of tension. As one worker explained:

I do find that not being an academic in a university, you’re a second-class citizen, your insights are never valued as highly as they would be coming from an academic. The staff in my department are nice and they try to be aware of it and counteract it. Then I notice things like chatting with someone or getting on well and thinking maybe we could even socialise after work. Then they’ll see other academics and then they’ll just start going: ‘oh, we’re having a social thing, hey, come for dinner at my house.’ And I realise they wouldn’t even think of inviting me.

As one academic worker reflective:

It is clear that academic staff are overrepresented when we talk about education. If you add admin, staff, security, staff, cleaners, librarians, catering, etc, Then you have very large sections of staff. So that actually what we think of as the traditional and core tasks, I think are actually probably the periphery at this point in the sector. That’s something worth thinking about.

There has been a long history of outsourcing across the sector, including cleaning, catering, and other parts of the institution. Over the past ten years in London there have been a number of campaigns by outsourced workers. As one worker explained to us:

Outsourcing has obviously been a kind of strong galvanising campaign issue in London, with cleaners and security guards campaigns being in the vanguard of the last few years of militant trade union activity in higher education.

However, there is also evidence of outsourcing beginning to spread into other parts of the university, including aspects of teaching support:

For the agency I’m with now there was some training they delivered on Instagram. Instagram videos, but the videos were literal videos of a screen, not actually uploaded. So that was my training. They employed me without checking my DBS. They were also asking me to go and support a blind student at a university on the other side of London. I’d had no training and that’s not my area. It’s just rampant, this zero-hour contract arrangement, everywhere you turn in education.

Higher education teaching clearly differs from schools in terms of the disciplinary function that lecturers play compared to teachers. However, as one lecturer discussed with us, that does not mean that universities are not expected to play a disciplinary role by the state. The growth of international students with visas has increased the pressure to take registers and monitor students. Beyond this, there has also been the introduction of “prevent”, a government anti-terrorism programme. As they explained:

It is a big issue in universities. There’s similar stories in schools, for example, in Newham of a teacher who refused to participate in the reporting on students and was disciplined and sacked. Obviously it also came with kind of a real attack on the liberty of teachers to discuss particular political issues that then was generalised last year with the kind of you can talk about anti capitalism in schools etc, which came out directly from the of the prevent policies. These were first normalised on on Muslim students and fighting so-called radicalization, and having to teach British values. It was kind of a multi-pronged attack, which was both about the kind of the political freedom of students to express themselves, the political freedom of staff to be able to kind of discuss some of these issues, but also a direct assault on people’s freedom at work, so that it was a real kind of managerial assault. I was part of a wider campaign which was called ‘students not suspect, educators not informants’ and at times also ‘preventing prevent.’

Changes in teaching and the class composition of students

The Prevent agenda is, of course, only one part of the changes to students’ experience of higher education. Clearly, their increased fees have shaped the experience of studying. Students take on heavy debt to study, which puts additional pressure on both their time in the university, as well as finding work afterwards. As one lecturer pointed out:

An obvious point to make is that the composition of students has changed. When I was a student we might have worked a bit of a job over the summer, maybe like a couple of people I knew worked during term time. But we had loans and I had a grant, and we spent all of our time arguing about politics, going drinking, and organising protests. Then we would do a bit of studying. That’s not the case for many of the students that I’ve taught over the past few years. Most of them have a full or part-time job. Maybe they live at home, they work, then they have days where they try and fit their studies in. The university for many students is no longer a place that you go almost every day and hang out and build those connections. Although I only really know London, it seems like there’s much more fracturing of the student population.

Another lecturer, working in a business school, noted that:

I used to do something in the first lecture I taught. I said to them, put your hands up if you’re studying management because your parents told you to? About half the class put their hands up. I would ask them are you studying management because you’re worried about getting a job? Pretty much the rest of the students. Then I’d ask them whether they would rather be studying something else like art? And a whole load of them would put their hands up. I would rather be teaching something else too. So you get this sense that management departments have a whole load of people who really don’t want to be teaching it, with a load of people who don’t want to be studying it. It’s really about the growth of credentials. Now you have to have a degree to do most kinds of white collar work. If you want better pay you’ll have to do a masters.

This was reflected in another comment by a lecturer:

Something which is quite different from schools is the social role of the university has changed quite significantly in the last few decades. For example, the sort of democratisation of the university and this mass growth of the need for white collar workers means that largely universities need to train students to be able to read, write and present information quickly and effectively. That’s what the vast majority of us are hired to do. We’re not hired at all to do research or have particular kinds of insights and stuff. We were hired to train white collar workers. What they study is almost kind of irrelevant. I think that’s partly what’s happening with a lot of these local disputes. In a lot of the post-92 universities there is a massive assault on jobs with particular kinds of departments being shut down. This is because there’s also a question of what is useful for these institutions that are supposed to be kind of mass teaching institutions. This is a contradiction in the sector that needs to be resolved.

Across these quotes, there is a sense that students are having an experience of higher education that is treated more as a commodity to be purchased and consumed, training for future work after graduation. No longer is the image of the lazy student drinking beer, watching daytime TV, or going on protests an accurate representation (if it ever was). Instead the university is more an expansion of training, with all the pressures of competition and fear for the future. In part, this can be seen with the decline of students’ unions as political spaces on campuses and the relative absence of a student movement in recent years.

Student mobilisations increasingly appear to be happening outside, and often against, the formal institutions of student representation. Student unions and national level organisations are increasingly pacified by their integration with university management, or transformation into broadly business-minded enterprises, whose internal disputes and institutional structures fail to relate to the grassroots campaigns of student populations facing increasingly hostile environments in which to politically mobilise. As campuses are ever-more hostile to international students, acting as extensions of the state’s border regime, and rigid to the demands of working-class and minority student groups, the student movement is in perpetual rise and fall. Although an increasing number of students are reliant on precarious jobs to sustain themselves at university, enduring rising rents and the necessity of taking on debt, new movements nonetheless continue to develop. From often highly-successful rent strike campaigns, to networks organising in support of the UCU strikes, students nonetheless remain a politically active, if marginal and disparate, political force. The increasing reliance of students on either part-time or full-time work to fund their university studies has also opened up new windows of opportunity. It has created a situation in which students are centrally organised in one large institution - the mass university - where they socialise and, in the experiences of many in the class composition project, become engaged in revolutionary politics. Yet on the same hand, these students are spending a large part of their student life in otherwise disparate workplaces. Therefore, whilst fracturing the political composition of students, the itinerant nature of student populations also presents the opportunity for struggles on centralised campuses to spread to a variety of workplaces through these student workers.

Class composition across education

Therefore, across schools, colleges, and universities it is clear that class composition is changing. Education is an important area of both work and preparation for work, making it a key site where new technical compositions are both experimented with and implemented. What happens in education has an impact, both directly and indirectly, on other kinds of work.

There are a number of themes that emerge across the sector. The first that is worth noting is the generational changes that are currently taking place. For both more senior teachers and lecturers (or professors), the conditions that they have worked under have significantly deteriorated for newer workers. One worker explained to us that this has played out differently in schools compared to universities:

It’s funny to hear the generational difference in schools with older teachers as more militant, because it’s exactly the opposite than in universities. In universities, the newer entrants are on crappy contracts. They are furious and want to join unions and fight. While the people who’ve been there for a very long time often just don’t want the boat to be rocked.

This is, of course, a generalisation, but the longer tenured university staff have tended to only fight over pensions, rather than falling wages and conditions.

Both schools and universities are one of the few remaining parts of the British economy with high levels of unionisation. However, as one academic worker warned:

On the face of it, it appears as though this union is incredibly radical and doing all the right things with national strike action on a near yearly basis. And that looks great, you know, given the climate that we’re in with the trade union movement. But in terms of workers at the rank and file relationship to branch level, it’s not particularly strong, especially amongst the casualized layer of academics.

This rings true for trade unions in primary and secondary education too - whilst seemingly appearing as strong from the outside, particularly since the Covid-19 pandemic, there is a significant lack of any strong rank-and-file politics that has been able to push and coordinate effective industrial action.

However upcoming strikes and crises in education provide a moment for a political recomposition of the workforce. As we are writing this, both Unison and UCU are balloting for strike action in the higher education sector, potentially providing a possibility of co-ordinated action on an industrial, rather than craft, level. Meanwhile, in primary and secondary education, NEU and NASUWT are balloting teachers for a nationwide dispute later this year. Unions representing support staff are also running indicative ballots on whether they will join these disputes.

The first challenge to this will be getting ballots over the line - particularly for non-academic staff in Unison who have far less history of nation-wide strike action. It will also be a challenge to ensure national unions take coordinated action, and motivate workforces into high-levels of participation in industrial action. However these are challenges that rank-and-file militants on the ground must take on if they want to build a serious recomposition of the industrial workforce.

The cost-of-living crisis also presents the opportunity to further a more united working-class political composition. Pay disputes present an opportunity to galvanise workers over a common issue, where traditionally different roles and geographical locations have fractured and divided them. Whilst secondary striking is illegal, and has therefore historically been difficult to achieve, the common issue of pay could be used to encourage meaningful solidarity across the sector, and improve the likelihood of achieving such action. However, these opportunities provide no guarantee - it will only allow for a fruitful political recomposition if militants in the education sector put the work in to build responsive rank-and-file organisation that can achieve this task. Indeed, the reverse could also occur, and the cost-of-living crisis could also encourage less refusal at work, as people feel more precarious and worried about what the future holds for them. Militant inquiry and intervention will therefore be imperative to shaping political recomposition to come in the sector.

-

Two Anonymous Teaching Assistants (2020) ‘Organising Agency Teaching Assistants’, Notes from Below. ↩

-

Ibidem (Ibid.) ↩

-

Labour Force Survey 2021, Office for National Statistics. ↩

-

A few examples of this are the 33-day strike against bullying and trade union victimisation at Oaks Park School in Redbridge; the multi-site strike against detrimental pension changes at the Girls Day School Trust; continuing strike action at Holland Park school against academisation; and a two-day strike in Huddersfield that successfully reinstated Louise Lewis, a victimised NEU rep. ↩

-

Two Anonymous Teaching Assistants (2020) ‘Organising Agency Teaching Assistants’. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

For a greater explanation of what exclusions are, why they should be opposed, and what the alternatives to exclusion are, NME’s pamphlet ‘What About The Other 29” and Other FAQs’ is a fantastic source of information. ↩

-

One such example is at Bannerman High School in Glasgow, where it is reported that teachers in the union NASUWT threatened to strike in May 2022 over poor working conditions that they blamed on a lack of exclusions. ↩

-

Angry Workers (20 April 2022) ‘An interview on the Pimlico Spring’, angryworkers.org. ↩

-

For an interesting example of this, see Angry Workers’ lockdown interview with two primary school students: Angry Workers (20 July 2020) ‘Lockdown interviews – Two primary school students’, angryworkers.org. ↩

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Healthcare Sector

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023