What is the rank-and-file strategy?

This is a transcript of a talk that Ray gave on the rank-and-file as part of a Notes from Below panel at The World Transformed in Brighton

In this talk I want to set out some principles for rank-and-file activists, exploring how to organize independently, and how we orient towards the trade union leadership or the trade union bureaucracy today. I will give some examples to demonstrate what a rank-and-file strategy looks like.

I want to start by saying that the most important divide in society is between workers and bosses. The class divide is structural to capitalism, and the relationship with bosses and workers is inherently unfair due to the power imbalance between capital and labour. The employment contract enshrines this imbalance in law and leads to friction over the wage effort bargain.

Workers have built organisations to help counter this and trade unions arise from this conflict. Trade unions have been developed to manage the bargain between workers and capital. Unions are contradictory beasts, and I think the nature of unions is best understood by understanding trade union officials and their position in society. They’ve got a different relationship with workers and rank-and-file negotiators because they are one step removed from the workforce. Most officers were typically reps in the past and were plucked out of rep positions to become full time officers. So, they have been taken out of the direct arena of conflict between bosses and workers and they, in effect, mediate between labour and capital.

So, officers are involved in the bargaining process. But unlike reps, they’re not exposed to the deals that they negotiate. Officers can walk away from a deal they negotiate without it affecting their day-to-day living, their wages, and that kind of thing. They are in a completely different position, I would argue, than the rank-and-file negotiators who are affected by the deals they negotiate and the changes to conditions that they’re involved in negotiating as well. And even if rank-and-file negotiators aren’t directly affected by the deals they negotiate, it’s likely that they have to sit in the canteen with people who are affected by the deals. They’ve got both formal and informal pressure on them. Officers don’t experience any of that.

It’s often said that “members are the union”, but it’s important to recognise that unions are also an institution. For workers, the union is a means to an end. But for officers, this situation is turned on its head, because officers will see themselves as custodians of the Union, its resources, and its assets.

Campaigns for improving workers’ lives can be seen as a way, by us, as building strength and building power in the workplace. However, for officers, campaigning is often seen as a way of building the union as an institution. For example, a senior officer that I know sees organising, recruitment, and the like as a way of creating a bigger fund base, so we can build up the officer cadre. That’s the officer’s approach to organising and that’s how they strategically see it as, as a way forward. Members are often prepared to take real risks, when they’re involved in struggle, struggles to overturn an injustice, to make the workplace bearable, to get better wages and terms and conditions and for this they can be sacked or victimised. Again, officers have none of this.

So, officers are more concerned with the union as an institution, and therefore more conservative. When the employer threatens legal action, the officer is concerned because this type of action can threaten the union as an institution. The great innovation of the Tory anti-union legislation was understanding this difference between officers and rank-and-file militants. What the legislation did, and continues to do, is put pressure on officers to police militant rank-and-file activists. And if rank-and-file activists overstep the mark and move beyond the boundary of anti-trade union legislation, then the union’s assets are threatened, and the institution is then threatened.

Sometimes this can be taken to ridiculous levels. I remember back in 2008, there was a strike at Argos in Basildon. At that time, we were in Amicus, which was a predecessor union to Unite. The head of the legal department, Georgina Hirsch, told the pickets at Argos that they were allowed no more than six pickets.

Now, if you’re familiar with the ACAS guidelines, you’ll know that this is only a guideline. It’s not a legal restriction, it cannot be mandated. She argued that if there was more than one entrance, and there’s three entrances in this Argos, you’re only allowed six pickets for the whole establishment. This is a weird interpretation of a guideline, which isn’t actually in any sense legal. Fortunately, the Argos reps had the confidence and the intelligence to ignore this ridiculous ruling. But you can imagine what would have happened if we had seven entrances or more. We would not be able to cover the whole of the establishment with your pickets.

What I think is more interesting about this example is that Georgina Hirsch used to be the head of the legal department for the Engineering Employers Federation. She was poached by Amicus, so probably offered a bigger salary, to come and work for Amicus. She came to Amicus with a mindset of a legal head of the Engineering Employers Federation, which then led to those kinds of contortions that our reps had to deal with.

Senior officers experience pressure from members, but they’re also under pressure from the state and employers. Sometimes the pressure is direct and sometimes it is less direct. Sometimes it’s reflected simply in the pay of senior officers. Senior officers are often paid salaries that are similar to those of senior managers. If you think about the circles that senior officers mix in, they spend a lot of time in Parliament, talking to MPs, they are in negotiations with CEOs and the like, you can see how that would influence the views of a senior officer.

I don’t know if you’ve read much Karl Marx, but Marx in the 19th century talked about how being determines consciousness. The trade union bureaucrat didn’t exist when he was writing this. But clearly, this term “being determines consciousness” applies equally to trade union bureaucrats as it does to workers and employers.

Officers face more pressure when members take action. The officer’s workload will be increased, and also members will expect and demand that the officers are more aggressive with the employer. But also, pressure comes the other way from the state if there’s a national dispute, and certainly from employers. I can remember five years ago, in London, there was a dispute brewing with British Airways at Heathrow. To be fair, the local union bureaucracy was really desperate to have a go at British Airways because they had been horrendous to our members. We got the ballot result for industrial action, the local bureaucracy was cock-a-hoop at getting the chance to have a pop at British Airways.

When pressure came from the Labour Party leadership via the Trade Union General Secretary, at that time Len McCluskey, they were told they had to back off. All the officers were wound up, with their reps, for an aggressive confrontation with British Airways, they were then stood down. They were stood down because not only was there national pressure on British Airways, national pressure on our members, national pressure on the Union as an institution, but there was also pressure from the Labour Party. That is the pressure that was brought to bear upon our members and the effect of that was the campaign was wound down.

The pressure from Labour is also very important when disputes have national and political implications. In normal times, union officers are a mediating layer who are under pressure from both sides and typically they vacillate. The longer an officer has been in post, the more likely they are to be far removed from members. Also, if workplace organization is weak then the pressure from the other forces will be greater.

When workers fight back, it throws up a whole load of questions about the trade union bureaucracy, about the role of officers, and workers have developed different responses to deal with that. Sometimes, if you’ve got good organisation, they just ignore the officer which I think is problematic. Sometimes people just blame officers which is never a positive approach to dealing with them. But there’s two other approaches which are quite common or have been quite common on the left. One is replacing bad officers with good officers.

I’ve seen this in Unite where you get good militant rank-and-file activists, and they get approached and poached to become officers. And typically, they’re quite good for a while, because they remember where they have come from. But the problem is not the individual, not the person, it is the social layer that the bureaucracy sits in. Over time, the pressure will be brought to bear on any officer, any half decent officer, and they will likely end up vacillating and selling workers out. Particularly if they are not involved in regularly representing members who are involved in militant struggles. And let’s be honest, there’s not many officers who are regularly representing militant struggles. I think that the strategy of replacing bad officers is problematic.

Another approach is what we would call red unions, breakaway unions, where workers in a particular union say they have had enough, and they’re going to break away and set up their own union. I can remember, many years ago, militant electricians and plumbers broke from the right wing EETPU and set up the electricians, plumbers, industrial union, EPIU. From the outset, it was met by a host of problems. Employers would not recognise them, employers would not negotiate with them, because they were far happier sitting down with a pro-business, right-wing EETPU. But the other problem, of course, was that they didn’t bring the majority of electricians and plumbers with them. And so, the majority were still in the old union, without an active left, that was able to challenge the right-wing leadership. So, it was the worst of both worlds really. Splits in unions are something that we would rarely support because if you’re not able to take the majority of members with you, it’s going to lead to a whole host of problems.

So, what is the alternative strategy? The alternative strategy is what we call the rank-and-file strategy. It’s best represented by the Clyde Workers Committee from 1915, when they said: We will support the officials just as long as they represent the workers, but we will act independently, immediately, if they misrepresent us. This was during the First World War and was when strikes were illegal. There were multiple unions in each workplace with strong organisation and democratic structures.

People may argue that perhaps it was of its time, which of course, is true. But I think there are important lessons from this kind of rigid statement that they produced. Working with officers so long as that represents good practice, it means that we can get access to the union resources to help us build up our workplace strength and develop solidarity with others in the union. We also must work out how we oppose officers when they take decisions behind our backs, or they negotiate deals that we’re not involved in. I think today “act independently” is about more than just striking. It’s about campaigning and organising at work in an independent way, that’s a key approach of the rank-and-file strategy. To build independence and build organisation in your workplace.

Building up confidence and independence in your workplace should be at the heart of how we operate, wherever we’re working. It’s not about building new unions on breaking away, it is about building across unions, typically in your own sector, building unity with whatever union people are involved in to try and build up workplace strength.

Working with and against officers is an important principle. It’s also a skill that’s learned through practice. The key is learning how to work with them to use the union resources but working against them when they are a barrier to building power or action. This strategy often means treating each officer differently, depending on how good they are, in the sense of whether they are prepared to support independent initiatives in the workplace. And if they are any good, they will change under pressure from the workforce.

I can remember I had an officer when I was working on a site in England. He came on site and over the course of a few weeks, I found out he was talking to HR behind my back. So, I just pulled him and said to him: “look, if you do that ever again, you’re never coming back on the site, right?” And ever since then he was brilliant. Whenever we had a problem we would say to him, we need to write to management and explain to them how we’re going to deal with this. And he said to me: “you write the letter and I’ll put my name on it.” That is how we operated after that, and it was perfect.

Advocates of rank-and-file strategy see the key division between left and right as less important than the divisions between rank-and-file and bureaucracy. It’s a constant theme of the strategy that informs our daily practice within the union structures and the workplace. This is more important when large struggles take place as well. But most of the time, things are quiet. But I would still argue that right-left division is less important than that between the officers and the rank-and-file.

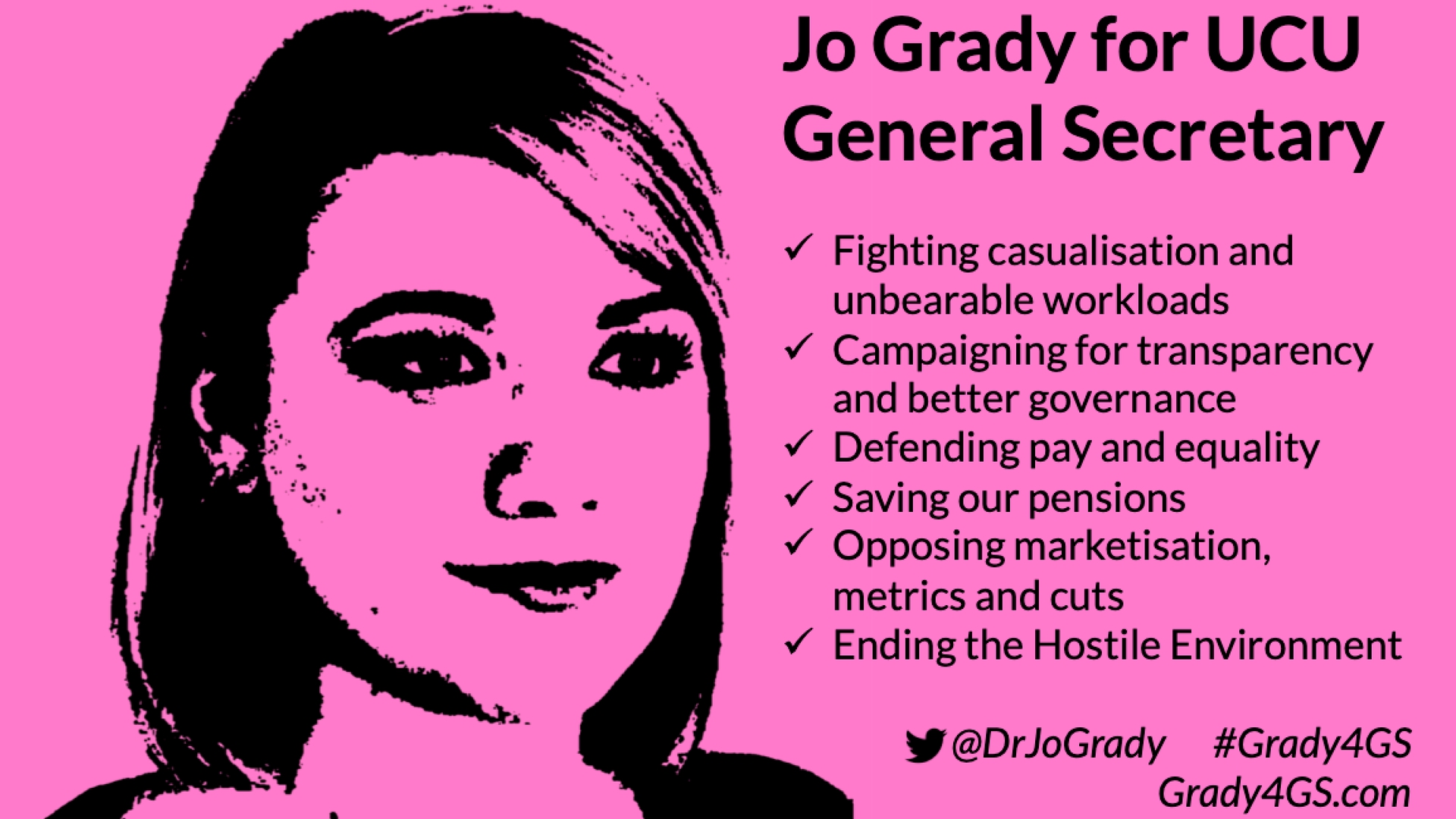

The last few points I want to make are around the question of elections in the union, because obviously we want to encourage our best fighters to become reps and workplace activists involved in the branch and all that kind of stuff. That can be taken as read. But then you get other elections in the union, for regional committees, executives, and all the rest of it. And I think it’s important that we try and work out collectively in our networks, how we approach each of those situations. So, if somebody is thinking about standing for the executive in the union, an important question would be - will winning that position help us raise the profile of rank-and-file struggles in the union and build the confidence of workers who want to fight? Or will the election more likely lead to the isolation of that individual with them becoming incorporated into the union machine and moving to the right? And these kinds of decisions have to be dealt with openly, democratically, and will often provoke not just discussion, but disagreement.

Now I want to use an example, which is one of the best examples, of how when this is done successfully, the impact it can have. I can remember, about 10 years ago, we had a couple of rank-and-file militant socialists on the executive of Unite. They would periodically challenge Len McCluskey politically, when that was necessary, but they would see the role as trying to feed big struggles through the executive to build support across the union, because Unite is a general union. If you had a struggle in health, or construction, or whatever, trying to get support across the union for those struggles is important.

For me, the best example is when we had a load of construction rank-and-file protests across the country. We were able to win the Unite executive to physically come out of their hotel beds in the morning to this picket. They came down to the construction protest to join an illegal blockade which closed down the site. I will go through in a bit of detail how that happened, because I think there are some important lessons around it.

In the summer of 2012, each week at 6am in London a construction site would be targeted. We would start off with maybe a dozen protesters, a big speaker system would be pumping out tunes, and there would be solidarity speeches from various people who come to join and support the construction picket. Once the crowd had built up to such a size, we would then rush the security guards and get onto the site and occupy it. We would hand out leaflets, recruitment leaflets, rank-and-file literature to the workers who were working on the site. Union density is incredibly small in construction.

As the site protests were building up, myself and others were on the Unite regional committee in London and Eastern. We were arguing on the Unite official committees for solidarity in support for these construction workers. We met huge opposition from the bureaucracy and from the left in the union as well, who saw factional disagreements with us and themselves as more important than supporting these construction militants. But after months of these protests and they were building up and becoming more successful, we eventually were able to win support in the Unite London and Eastern regional committee. They started sending people to these protests, people who had previously opposed them, were now coming to the site protests.

As we built up momentum, the construction rank-and-file activists targeted Blackfriars station, which was a huge project at the time for business in London, but also for the then Mayor Boris Johnson. It was one of those huge projects and so we decided to target that. Because Unite were now supporting the protest, they advertised it, there was a Unite/construction rank-and-file leaflet and posters that were sent around the union to try and build a presence on that picket.

This made it easier for us to build support. We had trade unionists from across London, students, and at the time there was an occupy protest outside St. Paul’s Cathedral. We got all of them to come down as well. There were hundreds of people at the protest. There were experienced construction pickets, seasoned anti-capitalist activists, students, trade unionists, who were able to link arms and shut down Blackfriars station. The day shift refused to work. The night shift refused to work. The Unite executive was there with the chair of the union.

It’s a fantastic example of workers solidarity and workers power. To think only a few months earlier, Unite had been ignoring this dispute. They had been allowing these construction militants to fight on their own. We had the combination of militant high-profile protests at sites across London which were attended by Unite reps from other sectors of the union who were also arguing within the structures of the union why Unite should support this struggle.

It was a combination of all those forces that shifted Unite into supporting that protest and organising that illegal blockade. More importantly, on the back of that, the union finally agreed to organise a national ballot for strike action at Balfour Beatty. Balfour Beatty was the main construction company driving the cuts to wages and terms and conditions. 35% cuts to wages they were seeking to impose. Once that ballot result was won, Balfour Beatty collapsed, and all the six other construction companies also collapsed like dominoes. You get an idea how effective that rank-and-file approach was, from the protests, the pickets, the arguments in the Unite structure, links to the protest, delivering illegal blockades and occupations, and finally a successful ballot for strike action that defeated all the major construction companies in Britain. For me, that’s the most important example, certainly in living memory, of the rank-and-file strategy being put into practice successfully with a bit of creativity, imagination, and more importantly determination and action.

author

Ray

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

NHS Workers Say No!

by

NHS Workers Say No

/

Oct. 16, 2021