The Charity Sector

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

March 21, 2023

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

Written by charity workers involved in the Class Composition Project

inquiry

The Charity Sector

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023

in

The Class Composition Project

(#16)

Written by charity workers involved in the Class Composition Project

Working for a charity is fun, but very demanding. Sometimes I feel like management fully understands the extra work we take on. We don’t get paid for extra work, instead we take time back which has to be agreed rather than when we want it. They also use the ‘family’ phrase a lot. Sometimes I feel like this is used in a way that we should be grateful, or as a reason to take on extra when we’re at capacity. Burnout is very common.

Charity work occupies a unique space in capitalism. Referred to as the ‘third sector’ it neither operates ‘for profit’ nor as an entirely formal part of the state, though increasingly charities are delivering outsourced services on behalf of the state, especially at a local level. Charities are often established with the goal of addressing some failing of capitalism; homelessness, abuse, environmental destruction, inequality, poor health, etc, though it is rare for a charity to have the express aim of getting rid of capitalism altogether.

And there is no wonder. The funding environment in which charities operate often sees them having to bid for funds from the state or capitalist philanthropists. And with median pay for Chief Executives at the UK’s 100 largest charities rising to £170,000 a year in 2021, those making the decisions about what is and isn’t in scope don’t appear to have much motivation to steer their organisations towards system change. You don’t bite the hand that feeds you lobster and caviar.

As a result, charity workers also occupy a unique space. Charity work often attracts empathetic workers who see the failings of the system, and want to change it, though our findings reflect a tension in charity workforces between those who think capitalism can be made better, and those who think it should be gotten rid of. Workers are sometimes reluctant to fight back against low pay or poor conditions, as they believe it would be to the detriment of the users of their charity’s service, or would be diverting money away from the worthy cause that they are fighting for. And according to the workers we’ve heard from, charity bosses are doing a pretty good job of convincing workers that they’re ‘a family’, that there’s no money available, or that they are making a sacrifice for the greater good, all of which affect workers’ willingness to organise.

As with many charities, there is a definite culture of expecting us to work overtime or out-of-hours out of the goodness of our hearts. Also, we are a small team because of limited funding, so we are all quite overstretched. Since everyone is in this position - management included - there isn’t much scope to negotiate workload. Apart from extreme cases where colleagues have experienced burnout and/or health problems, I haven’t heard of anyone speaking up about workload, hours or other decisions.

Despite all of this, we have also heard about some promising examples. From individual acts of resistance to collective unionisation campaigns, charity workers are fighting back. We’ve shared some of these examples later on in the chapter.

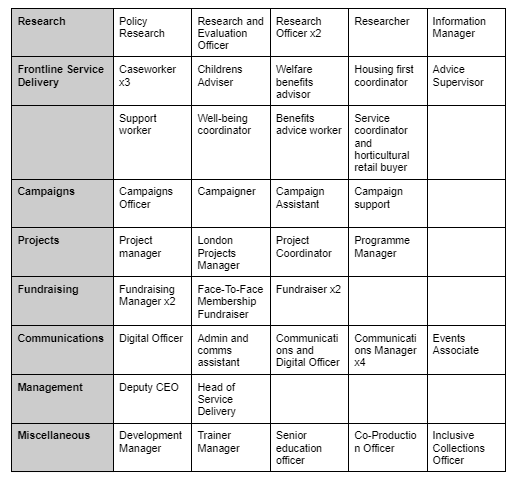

Job types

We received 45 survey responses from charity workers and conducted in-depth interviews with 5 of these. Job titles were mainly clustered around 7 job functions; Research, Frontline Service Delivery, Campaigns, Projects, Fundraising, Communications and Management. Though as our report shows, especially in smaller charities, job titles are treated as ‘indicative only’ and it really is a case of doing whatever needs doing. Looking at how workers have described their typical day, in some organisations ‘campaigns’ and ‘communications’ roles appear to be very similar, while in others they seem to be fairly distinct.

When asked to describe their typical working day, charity workers’ roles tended to be divided into one of two things, albeit with some exceptions. Workers either described days consisting of a combination of independent computer-based work and meetings (usually remote) or days consisting of client support and tasks related to this. Two workers described outreach roles, one as a door-to-door fundraiser and the other setting up information stalls and trying to recruit new supporters.

Some other noteworthy points from charity workers’ descriptions of their working days are:

-

Very few charity workers mentioned collaborative work with colleagues, other than passing references to ‘meetings’ or ‘zoom calls’.

-

While workers in communications roles didn’t generally describe undertaking tasks beyond this, several workers in other roles mentioned undertaking communications tasks (social media, video editing, blog writing, etc).

-

The most common interactions mentioned between workers were supervisory relationships.

-

Several workers talked about the intensity of their roles, either working longer hours than they were paid for, or undertaking tasks that fall outside of their official remit.

-

There is a strategic element to many roles in the charities sector, with workers frequently mentioning activities like writing funding bids, writing research papers or policy documents and undertaking tasks that require ‘strategic’ or ‘deeper’ thinking.

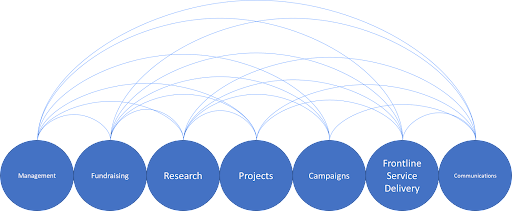

Although few workers focused in their comments on collaboration with colleagues, it’s interesting to think about the potential relationships between charity roles; the ways that workers’ roles might interact with one another in their relationship to the functioning of the whole organisation. The arc diagram below shows the ways in which these job families are interconnected. Take frontline service delivery for example. This function relies on fundraising for the budget to carry out its work, it is likely to be informed by research in the first instance, and research colleagues are likely to be involved in evaluating the service and identifying strengths and areas for improvement. Project management colleagues may carry out pilots, service improvement or redesign projects, and communications teams are likely to be involved in both advertising available services and celebrating successes.

Diversity

Our survey asked respondents to describe the diversity composition of the workforce in their organisation. In charity workplaces, two things in particular stand out. While some respondents said their workplace was diverse in terms of ethnicity, age, sexuality and gender, three-quarters of respondents said that their workplace is predominantly white, and over half said that it is predominantly female.

Other interesting but less prominent trends include:

-

Workplaces being mainly made up of workers from a single age group (most frequently younger workers), which is the case at just under half of our respondents’ workplaces;

-

Workplaces with a high proportion of people from middle class or wealthy backgrounds;

-

A third of respondents said senior management positions were mainly occupied by a particular type of person, usually white men.

Several respondents told us about specific diversity initiatives at their workplace. Some of these sound relatively tokenistic, like adding a diversity statement to job applications or insisting that two candidates shortlisted for any job opening must be from ‘minoritised backgrounds’. In one case, a worker told us that the organisation they work for is in the process of moving work from Europe to cities across the global south, which is likely to mean job losses for those on temporary contracts. However, the worker explained that they and their colleagues haven’t resisted this move, as they support ‘de-centring Europe in the organisation’.

Charity work and the pandemic

The pandemic led to acts of both individual and collective resistance by workers in the charities sector, with a third of respondents saying that they knew of individual colleagues or groups of colleagues who refused to do something as a result of the pandemic. At the individual level, workers refused to attend events and in-person meetings, or refused to visit clients’ homes. At the collective level, some workers collectively pressured management into closing offices at the start of the pandemic, though as time has passed, management are beginning to apply pressure for workers to return to in-person working.

Workers got together to demand a meeting with management which resulted in the decision to close the workplace at the start of the pandemic. Management has been forced to be very worker-oriented in terms of H&S during the pandemic, although this is now changing with demands that workers return to the office one day per week.

Over half of charity sector respondents said they felt their employer had kept them ‘completely’ safe during the pandemic, with a further third agreeing that their employer kept them safe ‘to some extent’. This picture wasn’t universal however, as one worker explained:

About 1/4 of the organisation has been classed as essential workers and have had to do face-to-face support work with members of the public. The safety measures put in place to protect them have been laughable. They have even had to buy hand sanitiser with their own money and then expense it. Although they were allowed to WFH for 3 months in spring 2020, in winter 2020/21 they were being forced to go in because the government told management they had to go (they run a service on a government contract). People caught Covid-19 at work and everyone was frightened. There was an open union meeting and an email was sent saying workers would discuss taking action and refusing to go if the situation wasn’t addressed (in January 2021). A compromise was agreed that they could WFH unless they had an appointment booked with a member of the public. This reduced the amount of time they had to be in the office and they accepted it because they still wanted the in-person service to be able to run because they care about the members of the public they’re supporting (bless them). I’ve been in meetings with management where it’s been abundantly clear they know nothing about the experiences this part of the organisation has been through and don’t give a fuck about their safety or wellbeing. This was pretty disturbing and there were some shouting matches between union reps and management.

All but four respondents said that they are currently working from home ‘all of the time’ or ‘some of the time’. Several respondents reflected on the impact of homeworking on the way their work is organised, and their employers’ plans for new ways of working following the pandemic. Two days a week in the office and three days a week from home is a common approach, and while two respondents spoke about staff raising the idea of ‘homeworking payments’ to cover things like increased energy costs, it is unclear whether any employers in the sector have agreed to pay these. Some workers reflected on the benefits for them of home working, such as more flexibility around childcare and part-time study, though as we will discuss later in the chapter, others have pointed out the negative impact on ability to organise.

When we were in an office, there were line managers who would be very eagle-eyed about when people came into the office, when they went on lunch and when they left, but this was not distributed equally so some people maintained autonomy while others were monitored heavily. Everyone moving to WFH has changed this and I think more people will be unwilling to meet the conditions previously imposed.

Overworked and underpaid

I start working at 8am quite intensely until 6pm. I try to take lunch breaks, but it’s just the nature of working in a small place. This has only been since January 2021. Before, I was part-time paid, but working full time hours, frequently working evenings and weekends.

Many of our survey respondents flagged issues with overwork or being paid for only part of the work that they do. Some workers link this specifically to the pandemic, while for others the issues appear to be longer-running. There is little talk of resistance to this, or where workers do attempt to push back, they report that this has little impact beyond individual cases. Workers appear to be mostly left to manage their own time, but several talked about working straight through the day with no breaks, accepting that this is ‘just how it is in these small charities’. Burnout, stress and anxiety caused by overwork are commonplace in the sector, but management appear to do little beyond offering ‘wellbeing’ subscriptions, paying lip service to ‘making sure everyone has a doable job’ or trying to control the narrative:

There was pushback to attempts to blame overworking on things like CCing colleagues in too many emails as opposed to simply taking on too much work and not enough staff.

Several charity workers referred in their responses to low pay in the charity sector. It’s difficult to find figures for pay in the charity sector from official statistics. While for many industries, there are specific categories in the Standard Industrial Classifications (SICs) used by the Office for National Statistics, charities are spread across categories, depending on the area in which they operate.

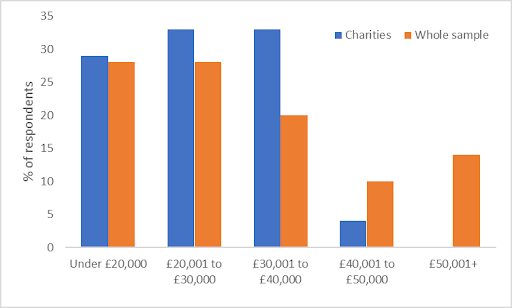

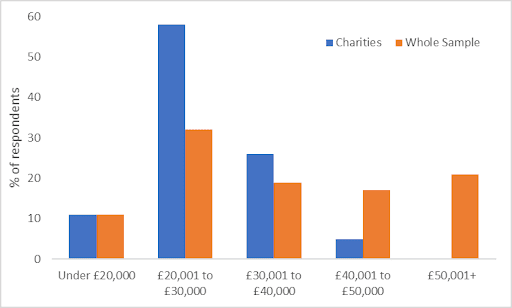

Analysis of the salary data from our Class Composition Survey, however, shows that charity worker pay is clustered at the lower end of the earnings distribution. No charity workers said that they are paid over £50,000, compared to 14% of workers across the whole sample. Looking at just full-time salaries, 21% of workers across the whole sample said that they are paid over £50,000, again compared to no charity workers. Because we collected salary data based on earnings brackets, we cannot produce median salary figures from the data. However, we can see that the median earnings bracket for full-time charity workers is lower than it is for workers across the whole sample, standing at £20,001 to £30,000 for charity workers compared to £30,001 to £40,000 for workers across the whole sample.

Looking at recent pay policy, workers report a mixed picture. While some spoke of pay freezes, below-inflation rises and even in one case pay cuts, others mentioned more positive changes, in one case as a direct response to worker demands.

Union members voted to include exploring moving the whole organisation to a 4-day week in the pay claim. Management said no. Union members voted to reject management’s pay offer. Management has now set up a working group to explore a 4-day week.

Two workers reported changes in pay systems leading to more pay clarity and pay rises for all or most staff. Other changes include the introduction of performance or experience-based pay systems, and in both of these examples workers report a lack of clarity about how workers can expect performance ratings or levels of experience to translate into pay rises. Lack of pay progression appears to be commonplace in the sector:

I am currently organising some colleagues around the fact that we are paid less than our peers simply because we didn’t work for the charity when they were given it. The raise was to do with retaining staff but the charity has since gone back to paying newly employed fundraisers around £2,000 less than those who were working in 2019. The job is advertised with a pay scale that is only relevant as an initial offer of pay as opposed to a pay bracket that people can move through.

In addition to the retention problems created by a lack of pay progression, some workers reflected on the impact of low pay on their organisation’s ability to fill vacant posts in the first place. In one case, a worker reflects that rather than increase pay and recruit the skilled staff that they need, their organisation has opted to recruit unskilled staff on lower wages. This is likely to further exacerbate the workload issues we considered earlier in the chapter, as staff with the relevant skills and experience have to compensate for staff without, potentially creating tension between skilled and unskilled staff.

Management are very resistant to any pay increases but a lot of staff want pay increases. Management frequently and openly discuss having real issues with hiring, they are struggling to hire staff into challenging support roles (especially when the pay they are offering is so shit) and for benefits advice work (my job) it is very specialised and difficult to hire for so they now recruit for ‘trainee’ advice workers and pay them significantly less but they are reluctant to invest a lot of money in paying for training.

Temporary work

Like many third sector workers, I’m on a short term contract which leads to constant job insecurity. It makes it hard to plan for the future and ever really settle in, as you know you’ll be leaving sooner rather than later. This is my 5th short term contract in 4 years, and I am tired of the insecurity.

Temporary work is common in charities, with 25 percent of our respondents in the sector stating they were on temporary contracts. This rises to 31 per cent when freelancers are included. By contrast, the Labour Force Survey produced by the Office for National Statistics shows that 6 percent of employees across the whole economy were classed as ‘temporary’ employees in the three months up to January 2022. Unsurprisingly, this leads to a fear of redundancy, with 36 percent of charity sector respondents saying that they either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ with the statement ‘I am worried about being made redundant’, compared to 28% across the whole sample of respondents.

They are laying off people in one team who were employed on full time contracts for 6-18 months, but also making some permanent staff redundant. They blame lack of funding.

Temporary workers are easy targets for layoffs, with one respondent telling us that their organisation is shifting work out of Europe and is likely to lay off workers on temporary contracts as a result. They explain that while they and their colleagues agree with the principle of ‘decentering’ Europe in the organisation, they had been led to believe that there was a high likelihood of the post becoming permanent when they started.

The programme is funded to 2023, so I am on a temporary contract for the duration of the programme.

Some respondents explain the prevalence of temporary contracts as being linked to funding. Funding models for charities vary, with some raising funds directly from those who support their cause, others receiving funding from public bodies to deliver services, and some relying on grant funding, for example from local government, the Arts Council, the European Social Fund or the National Lottery. Even for charities that rely on a ‘trust’ or ‘endowment’ to fund their activities, there are often restrictions on how this is spent, and the charity will often need to look for external funding sources for some elements of its work.

Most of us are brought on by charities who claim they don’t have the cash for full time work, I am self employed and have to send an invoice each month. My employer could turn around and cancel my work today.

There is downwards pressure on many of these funding sources. No further European Social Fund money will be available to Britain after 2023 as a result of Brexit, and it is unclear whether the Government will replace this with anything else. Local Government budgets continue to be cut, and this has already led to significant reductions in budgets for services and grants. Household incomes are facing a significant squeeze, and so individual donations are likely to come under increasing pressure. In this context, charity workers are likely to see increased casualisation, and will need to be ready to organise to resist this.

I wanted to join because I get the impression that freelance work in the charity sector is getting worse, with more work outsourced in increasingly insecure ways. I’d hoped to meet other comrades in this position but haven’t yet and haven’t had the confidence to really talk about this with my wider union.

But the prevalence of temporary contracts has an impact on workers’ confidence to organise at work. Several respondents reflected that theirs and their colleagues’ temporary status is a barrier to them organising. In one case, a worker told us that there is a push for union recognition at their workplace, but their ‘fixed-term’ status means that they are nervous about being openly involved, with their manager encouraging them to ‘put themselves out there’ in the organisation to try and secure future work.

Since the majority of us signed onto fixed-term contracts, we don’t feel we have much power to offer input.

The Challenge of Organised Resistance

Competitive tendering for projects is massively undermining our union efforts. Make demands for pay increases for lower paid staff? Management says it’s impossible as we won’t be competitive when trying to secure funding anymore. Try to reduce working time? We won’t be competitive anymore when making funding bids. The use of fixed-term contracts also makes recruiting people into the union much harder and means people don’t want to fight because they think they’ll be leaving soon anyway. Broadly across the organisation we massively struggle with atomisation - people in different locations and different directorates and teams don’t know what’s happening anywhere else in the organisation, which makes building solidarity hard. The pandemic has exacerbated this.

Just over a fifth of charity sector respondents said that there is a recognised union in their workplace, most commonly Unite. The most common unions among our survey respondents were IWGB and Unite, with each representing around a quarter of respondents. A further two-fifths of respondents said that they knew of union members in their workplace, but that no union was ‘recognised’ by their employer, which ought to be an indication of the potential for organising in the sector.

However, our survey respondents pointed to several barriers to organising, some of which are charity sector-specific and others of which are common in other industries. The first is financial. Where charities need to bid for contracts, the argument is that higher costs will make them less competitive against other bidders. For those that rely on grant funding, funders may stipulate maximum hourly rates that they are willing to fund, and the amount of funding available has often been reduced as local government budgets are cut. At one West London council for example, the maximum amount of grant funding organisations could be allocated through the ‘Community Grant’ in a year dropped from £30,000 to £15,000 over the course of four years, from 2015 to 2019. Charity workers need to be able to understand where claims of financial hardship are genuine and where they are being used as an excuse.

The prevalence of temporary work is a second barrier to organising. This manifests in several ways. In some cases, workers want to organise but are worried about losing their job/not getting a new contract, and so they don’t have the confidence. In others they don’t feel invested enough in the workplace to want to spend their time and effort organising. And in others still, they believe that as temporary workers they have no power.

The pandemic has increased the atomisation that some workers say was already there in their workplace, and workers talk about the difficulty they have had building relationships with their colleagues while they are all working from home. There is nervousness about using company tools such as email, MS Teams and Slack, but because workers don’t know one another well, they find it difficult to identify alternatives.

Some workers talk about ‘staff panels’ or ‘forums’ being established by managers to try and counter unionisation efforts. Nobody speaks positively of these, with them being described by our respondents as ‘toothless’, ‘useless’ and ‘under management control’.

One of the biggest barriers to organising is guilt, with workers expressing reluctance to negatively impact the charity’s users. This is similar to what we’ve heard elsewhere, with managers in small businesses appealing to the notion of ‘family’, and this narrative is certainly prevalent in charities too, but there is more to it in the charity sector. One worker talks about a history of worker organisation where they work, but explains it’s difficult to translate this into action in a charity that works with refugees and asylum seekers. Another talks about how working at a disability rights organisation the lines between work and being part of a movement are blurred, which again makes stopping work difficult. And this guilt doesn’t just stop workers taking industrial action, in some cases it stifles organisation altogether.

I feel awkward about it in the sense that as a charity and disabled organisation, you can feel morally obligated to go beyond average job expectations.

Several charity workers told us about the individual acts of the resistance that they use to make their own situation more bearable. These are mostly centred around refusing to work overtime and sticking to contracted hours, although there were some more novel approaches, like the worker who told us that they just lie to their boss about what they’re doing, and the one who steals time in the day to read about Marxism. But these workers all recognised that these individual acts of resistance are limited in their ability to make lasting change either for themselves or the broader workforce.

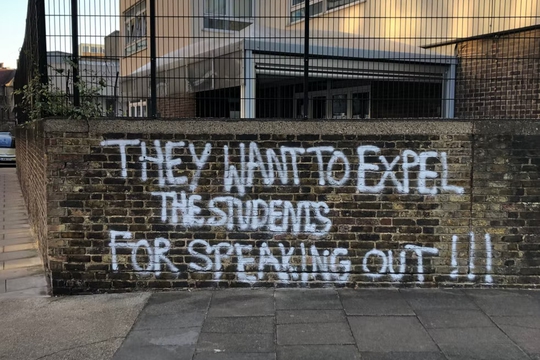

Despite all the challenges above, there are examples of charity workers organising. A worker at a medium-sized charity (260 employees) told us that workers there are determined to unionise, with more joining the union every week. At the time of writing, the employer and the union had entered the 20-day negotiation period to explore whether agreement could be reached on voluntary recognition, with workers making clear to the employer that they intend to launch a formal process should the employer refuse to recognise their chosen union. The workers have set up a whatsapp group to communicate privately with one another, but those who feel confident to do so are also posting openly on the charity’s Slack channels, including to counter the misinformation being spread by the charity’s leadership team.

Conclusions

The charity sector is characterised by low pay, overwork and increased casualisation, all of which would elsewhere point to a high potential for organising. But workers are often in the sector because they are passionate about the work that their organisation does, and for smaller organisations at least, reduced availability of funding is a genuine problem.

Where workers are resisting, there are more examples of individual acts of resistance than successful collective organisation and action. Workers report being a lone voice struggling to organise with their colleagues, and often seek solace in union branches, which are populated by other ‘lone voices’ from different organisations. But with several different unions all operating in the sector, there are several of these charity worker branches operating independently from one another.

Based on our research, we think there are three things charity workers can concretely do:

-

It is important to know the genuine financial situation of the organisation you work for. While some charities’ claims of financial hardship are genuine, claims of this type are a standard argument employers use to justify attacks on workers, and are often untrue. If you know the genuine financial situation in your workplace, you can tailor your organising strategy to match it.

-

With so few examples of successful organising in the sector, it is important that as charity workers we share what we know about what works with one another. With workers split across several unions, we need to find united ways of organising together.

-

While many charity workers express contempt for the way their work is organised, decisions about the shape of the sector are often made by executives, with the voices of those who do the work going unheard. Talk to your colleagues about what a better version of your work would look like, and the concrete steps you would need to take to get there. We’ve heard through the project about user-led models and about bad Chief Executives being removed by trustees. Talk to your colleagues about these examples, and convince them that change is possible.

Charity Case Study

I work for a small mental health charity, and while my job title is technically a communications-type role, my day-to-day work encompasses so much more than that, from front-line work to fundraising, to admin, to training other staff. In a well-organised workplace, this could be beneficial, because it means you’re getting more experience in different tasks, but in my workplace, things are pretty chaotic, so it often feels like you’re not sure what you should be doing and things get missed.

Because the organisation is so small, it doesn’t have the same support functions that larger, better-funded charities have. I’m not a fan of HR departments, but the lack of any knowledge around some of those basic functions does lead to some poor working practices. I haven’t seen my contract, I don’t receive pay slips, I don’t have set hours. And benefits that employees are legally entitled to, like pensions and paid leave, are difficult if not impossible to access.

I’ve had bad jobs in the past, and obviously partly that’s why you join a union, you build up the relationships with your colleagues, and then you have collective bargaining power. You’re not just operating as individuals with your own individual opinion. But the way we work means it’s really difficult to build up allies, we don’t work in the same place and we don’t have any tools like Slack to contact one another, only personal emails.

I’m a member of Unite, and I’ve found it reassuring to go along to branch meetings and get advice and also connect with others on these short-term contracts, which seem really common in charities. My partner is an academic and I see the same thing is getting really common there too. But there’s other connections too, like this narrative of ‘you really care about this thing so you should feel lucky to work here’ which is used as an excuse to treat you like shit. Or like ‘There’s no funding, if you want better pay and conditions, go work in the corporate sector.’ I also heard about a small charity where people didn’t have contracts and they did a campaign and they actually won, so that’s quite reassuring.

While the organisation does have a small office, since the pandemic it’s not really used, and so it can be difficult to build relationships with other workers. There’s a bit of a split in the attitudes of some workers, for example on trans issues, and atomisation means it’s difficult to address these as political issues rather than interpersonal disagreements. Our manager isn’t immune from these disagreements, and doesn’t really respect professional boundaries, discussing their personal views of one staff member with another, for example. And this extends into other aspects of their relationship with us, like sending us a bunch of emails in the middle of the night that are then waiting for us when we wake up and log in.

The organisation says that it really values lived experience, so lots of the staff have experience of mental ill-health. That was a big draw to me for working here, and I’ve seen other organisations that do a really great job of encouraging workers with lived experience to bring their whole self to work, and really offer them the support they need to do that. But I think in an organisation where it’s not managed very well, and you’re encouraged to bring your whole self to work, it can actually be really emotionally damaging when that’s abused, or it’s not taken into consideration, because, obviously, then it feels much more personal. I actually think that’s partly why so many of the issues in my workplace become so personal.

I think because the organisation is user-led, there’s a definite political aspect to it, which is quite emotionally draining, because it means you’re also trying to fight for something in a political sense. Ultimately I think my view is that I don’t think charities should exist, but given that they do I think it’s right that they should be user-led, but I think they also have to be managed well.

Featured in The Class Composition Project (#16)

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Education Sector

by

Notes from Below

/

March 21, 2023