Minority Strikes Can Work

by

Bethany Kosmicki,

Matt Ford

July 3, 2023

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

An Account from Graduate Workers in Philadelphia

inquiry

Minority Strikes Can Work

An Account from Graduate Workers in Philadelphia

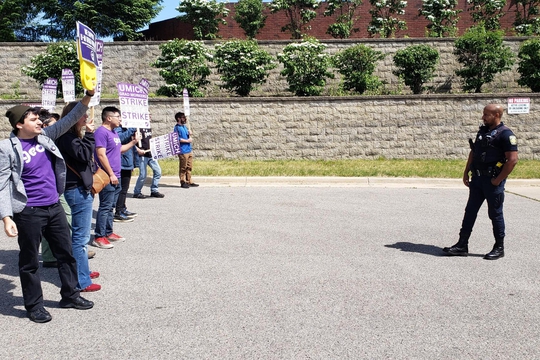

On January 31, 2023, the Temple University Graduate Students’ Association (TUGSA), the union representing graduate teaching and research assistants at Temple University in Philadelphia, went on strike. After over a year of stagnant negotiations, we were left with no choice but to walk off the job. In the following six weeks, management cut off our healthcare, rescinded our tuition benefits, and threatened the immigration status of hundreds of workers, all while refusing to bargain for weeks at a time. Despite the harsh winter weather, betrayal of many professors, and management’s unprecedented retaliation, our pickets held strong. The strike grew throughout its duration, and only one of the hundreds who went on strike chose to return to work. By mid-March we’d won the best contract in our history, which includes, among other wins, significant wage gains, an elimination of unequal pay tiers, improved dependent healthcare, and increased parental leave.

Striking was essential to winning a fair contract, yet it could not have happened without years of strategic, disciplined, meticulous organising and deliberate organisational structuring. This pre-history also explains why our maximal demands were ultimately unreachable in this contract cycle. Reflecting on the strike has allowed us to articulate the organising approach that provided the foundation for our solidarity over those trying six weeks. While we did achieve real gains in regard to each of our demands, we fell short in the magnitude of those wins. Yet the ultimate testament to our solidarity was in the near unanimous recognition among TUGSA members that our fight is necessarily longer than a single contract campaign.

TUGSA looks markedly different than it did just six years ago. Like other contingent workforces, we face extremely high turnover in our bargaining unit – between 30-35% each year. Organising therefore requires an immense amount of time and effort to maintain membership, and even more to grow it. Likewise, a decrease in organizing efforts for even one or two terms can lead to a massive drop in both membership and participation. For many years TUGSA’s organizing strategy was wholly inadequate, if not nonexistent. Bargaining previously had minimal participation from its small membership and illustrated the urgent need for a long-term strategy of rebuilding our union.

By the time we were voting to authorise a strike in November of 2022, density had grown from single digits to over 60%, with engaged workers from all across campus. Over a two-week span, TUGSA’s leadership held a dozen in-person meetings where members could vote. Offering different dates, times, and locations around campus gave every member the opportunity to attend. Maximum participation meant members were actively (not passively) engaged in the decision-making process and fully informed about the possible outcomes of a strike. This resulted in an inclusive and participatory structure which helped to build trust, transparency, and an active and engaged union community.

Rather than strike immediately, we made the strategic decision to wait until the Spring semester. Despite the success of our broader strategy over the past several years, high turnover and entrenched anti-union sentiment throughout Temple’s organizational hierarchy posed the real prospect of a minority strike against an exceptionally hostile employer. Though membership and engagement were not evenly distributed across the University, committed. TUGSA members’ jobs were located in key areas where a work stoppage would cause significant disruption.

We notified the university on the morning of the first day, right when pickets began. In response, Temple refused to bargain and sent more intimidating messaging to our members, including illegal threats to immigration status. We spent the first week picketing in the cold and rallying media attention and support from campus and union allies.

The second week of the strike put our organising methods and union structure to their most serious tests yet and laid the groundwork for getting through what followed. Once the strike began, Temple refused to bargain on-campus any longer. Continuing open bargaining off campus would have meant removing members from the line to attend the sessions and incurring high expenses for the location rental. Though solidarity was high, we knew our power was limited. From ad hoc meetings and on-the-line discussions, a question emerged: would we expend some of our limited power to fight over the format of bargaining, or would we put that energy toward winning material gains? It was clear the latter was the obvious choice, and we quickly developed new methods of shared decision making. This decision could not have been made if members had not already seen bargaining sessions over the past year and formed trust in the negotiating team’s ability to fight for our demands.

That same week, Temple abruptly cut off our healthcare. They had previously threatened to do so, as many employers do, but this was the first time in U.S. history that a graduate union’s healthcare had actually been terminated. Members learned this when they were turned away at the pharmacy trying to pick up prescriptions, or at the doctor’s office for their children’s appointments. Though Temple’s jarring cruelty created an urgent issue, our preparation and frequent meetings meant that members were not caught off guard. However, we now had to navigate the reality of not being able to access healthcare, and prevent a panic where members started returning to work. This challenge produced inspiring acts of solidarity from members. Those who didn’t need urgent access to care chose to remain without insurance during the strike so that strike funds could be directed towards those who needed care immediately.

With Temple facing increasing public backlash, we took the opportunity to show them that this unprecedented attack had failed. Previously they had been dramatically downplaying our numbers in messaging and the press. The day after cutting our healthcare, strikers emailed their direct supervisors and university administration explicitly declaring their intent to remain on strike until a fair contract was reached. This not only made clear to management that they couldn’t avoid our numbers, it also strengthened solidarity on the line. For the rest of the strike, those who joined sent emails of their own. It was no longer enough to not show up for work, we were demonstrating a real commitment as well.

The third week put this commitment to the test. Temple made us an offer that was woefully insufficient, coupled with the implied threat that unless it was put to membership for a vote, they would stop bargaining completely. Despite the risks of holding an official vote on a bad deal, the previous weeks had illustrated members’ commitment. A vote to accept the deal meant ending the strike with minimal wins, while a vote to reject meant the strike continued. The deal was rejected by nearly 95% of members, sending a message to Temple that we were prepared to stay on the line until they were willing to pass something of real substance across the table.

Over the next two weeks we escalated picketing and ramped up our messaging and recruitment and held strong after missing our monthly paychecks. Through the combined effect of these efforts, growing negative publicity for Temple, increased support from our allies, and, most importantly, the university feeling the strain of our withheld labor as mid-term exams neared closer, we finally pushed them to offer a fair contract after a grueling few days of bargaining.

After another round of well attended meetings, we almost unanimously accepted the new offer. Winning for us did not mean we ended up with a contract that met every demand we started with. In some parts it even meant only incremental improvements. However, the major wins reflect a massive success for a minority strike of graduate workers against a notoriously unforgiving administration. Accepting the offer meant recognizing that with significant but ultimately still limited power, our fight must necessarily be longer than a single

contract campaign. Going forward, we have the opportunity to build on an organizing model and structure that has proven effective under the direst of circumstances. While TUGSA is the strongest it has ever been, it is new to this strength, and it will take sustained efforts in future years to continue winning the transformative gains needed to give graduate workers their deserved pay, benefits, and rights.

Our reflections in this account also make the real stakes of strategy and discipline in labor organizing more apparent than ever. An absence of real discipline, an emphasis on abstractions over concrete realities, the scourge of petty infighting and tolerance of bad faith actors, a lack of clearly defined roles, and the dangerous tendency to offer forms of participation that are as easy and commitment free as possible for our fellow workers – each of these can be both the cause and result of flawed organizing approaches. The negative effects of the wrong organizing model can spiral out of control quickly and take years to recover from. Most importantly, these reflections provide us with the knowledge necessary to grow our union’s strength and further refine our organizing tactics in preparation for the years ahead.

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Reflections on a Teaching Assistant Strike

by

Michael Mueller,

Lucy Peterson

/

July 3, 2023