Reflections on a Teaching Assistant Strike

by

Michael Mueller,

Lucy Peterson

July 3, 2023

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

Strategic lessons from graduate organisers at the University of Michigan

inquiry

Reflections on a Teaching Assistant Strike

Strategic lessons from graduate organisers at the University of Michigan

For decades, neoliberal capitalism has waged a continuous assault on the working class: heightening exploitation and inequality, hollowing out public institutions, and neutralising class organisation among workers. Unfortunately, much of the labour movement has been defanged and bureaucratized, operating within a defeatist framework that leaves itself unequipped to defend itself against any attack, let alone create meaningful change in the direction of worker power and socialist progress. However in recent years, there has been a growing militant strike wave within the US labour movement that has clarified the contradictions of the workplace and shown the possibility of rebuilding class organisation.

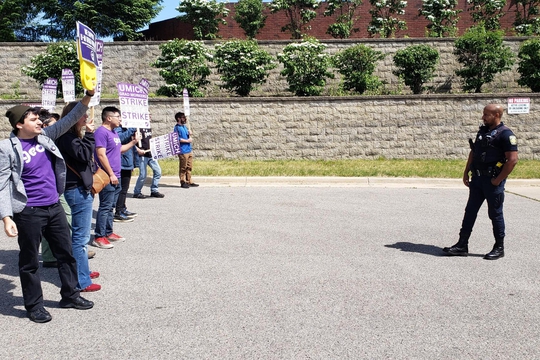

At the University of Michigan, graduate workers have moved toward increasing union militancy in recent years. In Fall 2020, rank and file members of the Graduate Employees’ Organization (GEO) organised an emergency nine-day strike against UM’s failure to meet campus safety needs in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and national uprisings against police violence. Building on this experience, our 2022-2023 contract campaign – centred on a living wage and a dignified workplace – brought workers into confrontation against the boss, culminating in a month-long strike throughout April. While our contract campaign continues to an uncertain end, the strike has raised expectations and significantly shifted the terrain of workers’ struggle at UM. We can say with confidence at this point that we have called the balance of power into question and created an occasion for real, direct class struggle, something that the U.S. labour movement has stifled for decades.

Building commitment to resist the boss

Just a few years prior to the 2023 strike, GEO was a very different union, a union where an open ended, long-haul strike was outside the bounds of the kinds of actions we considered taking collectively. However, taking action in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic heighted participation and militancy among UM grad students and gave them direct experience of the university’s intransigence. That collective knowledge and experience was the foundation upon which we built a contract campaign that radically broke from the conventional approaches. In November, GEO members affirmed the importance of open negotiations accessible to all workers. This brought us into an unexpectedly bitter confrontation with the HR team of the University, who insisted on bargaining in small, closed rooms. After agreeing to an open first session, HR illegally refused to attend the second session and spent the next two months employing every tool at their disposal to get our bargaining team to meet them in a closed room. Once direct action forced HR’s hand to meet in open bargaining sessions, this episode, as well as the disrespect workers experienced at the table, built a committed core of workers deeply mistrustful of the boss.

Without any serious movement from the University, graduate workers held a strike authorization vote in late March. Days earlier, the University leaked a plan that would provide summer funding for qualifying PhD students and refused to bargain on the subject; eligible workers earning only $24,000 yearly paid over eight months would receive an additional $12,000, nearing our living wage demand (a 60% raise to $38,500). Many workers recognized this strikebreaking move as a reflection of our power, and were ready to fight to codify this funding in our contract and expand it to all workers. The vote passed overwhelmingly, and we went on strike March 29.

Perhaps our most significant anticipated challenge was the prospect of resisting a court order to return to work. In Michigan, public sector strikes are illegal, and our contract (which did not expire until May) contains a no-strike clause. We were particularly sensitive to the challenge of striking under threat of an injunction because UM had broken our 2020 strike with this very threat, amid internal disunity and significant misconceptions about the nature of an injunction. A relatively significant layer of workers believed that even if we did strike, the University would be able to break us in a matter of days by going to the courts. Given this context, we reached internal consensus among our department organisers to inoculate members to strike, even under a court order to return to work. In the end, the University’s injunction request was denied by a judge, a significant moral and material victory.

Locating and exerting our power

As UM failed to break the strike through a court order or through docking pay, and as they nevertheless stonewalled us at the bargaining table, we found ourselves faced with the task of winning a long-haul strike. Unlike undertaking demonstrative actions, such as rallies and brief strikes, striking to win means seriously disrupting the employer’s operations, which may take significant time in the context of a graduate worker strike. Determining what it takes to win requires building a collective understanding of the source of our power and of the functioning of the university itself, including the contradictions which heighten under the weight of a labour action.

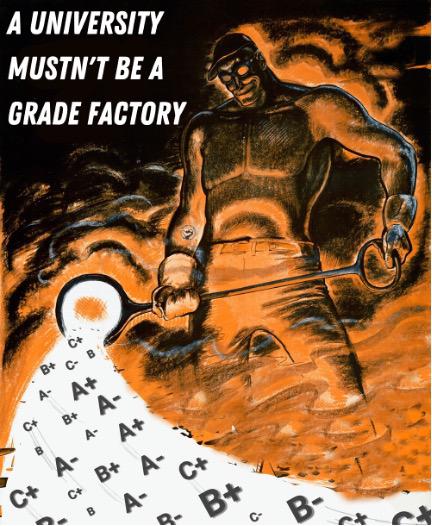

What ultimately became clear to us was the ability of the university to withstand missed instructional hours in the short term. Faced with the choice of either settling the strike or withstanding it, week after week the university made the choice to withstand the disruption to classes. Administrators provided a variety of mechanisms for enabling this: by recruiting scabs (particularly faculty), pushing instructors to adapt course syllabi, encouraging self-study, and combining sections. The apparent ease with which management moved through this period suggests that a few weeks of withheld instruction alone – especially by graduate workers, a minority of campus instructors – may produce less impact on the degree production process than we would imagine, in part due to the possibility of accommodating this disruption through scab labour.

As the strike neared the semester’s final grading deadlines, many workers became increasingly implicated in the strike. Some faculty supervisors who had spent the weeks prior navigating the strike with relative ease were taken by surprise when they found themselves in the difficult position of needing to scab withheld labour themselves, adapt their courses to make for easy grading, or withhold their grades. Meanwhile, administrators directed faculty to turn in grades, giving guidelines to alter syllabi and misinforming faculty that any withholding of grades would “harm” students. Many faculty accepted this narrative and blamed strikers, while others expressed anger at the administration for letting things spin out of control. The most organised faculty mounted an initial collective response in the form of a pledge to withhold grades until May 12, past the University’s “hard deadline,” a promising effort that unfortunately did not continue beyond that point. Ultimately, most supervising faculty actually either did the work of grading or otherwise calculated grades based on partial work.

Perhaps our most significant misunderstanding with respect to our analysis of power was the extent to which graduate workers’ labour is mediated by other instructional workers. Since these instructors had not been organised into collective militancy, the University was able to use them as a shield to deflect the full power of the strike. So while we successfully disrupted the pedagogical outcomes across a wide variety of courses, we were less successful at interrupting the production of transcripts and degrees.

The University faced its greatest challenge to maintaining a veneer of legitimacy in its response to strikers who were graduate instructors of record. Without faculty supervisors to enter grades, the University nonetheless insisted departments find a way to enter grades, revealing the extent to which the production of transcripts truly is something the University cannot seem to function without. In many cases department chairs, facing increasing pressure from deans to enter grades, chose to give A’s to all students in classes with striking instructors of record.

While any prolonged strike calls the legitimacy of grades into question, the University’s move to hide the absence of graduate labour in the production of thousands of grades – including many cases of outright fabrication – was, to our knowledge, an unprecedented response. The consequences, such as possible blowback to the University via accreditation issues, reputational costs, or downstream impacts on fall semester courses, remain to be seen.

Looking ahead

Having concluded the winter term with little bargaining movement from the University, and with grades entered, graduate workers now find ourselves in a period of reflection and regrouping in anticipation of resuming our strike after the summer break. Processing this situation in collective settings has revolved around assessing our winter strike and building an understanding of our next steps.

We believe our experience points to a need to make further space in our organising, and in our theoretical approach, to the organisation of non-graduate campus workers – particularly faculty and staff – and their relation to the administration. The University’s ability to weather our winter strike hinged on the cooperation of faculty either ready to scab our labour or unhappy but too disorganised and atomized to mount a serious refusal. In the fallout of the strike, many faculty have expressed frustration at the administration’s behaviour. We hope that summer organising among allied faculty, and increased outreach to non-graduate workers in various forms, will pay dividends come the fall.

Most crucially, our success depends on accumulating disruption to the point that the University can no longer accommodate our withheld labour or divert the disruption away from its intended target. Our winter strike has intensified certain latent contradictions of the University which may bear fruit in fall, as we find ourselves mounting a further blow against a still-standing but nonetheless bruised administration. The University has shown unexpected resilience, but we continue to build power for the long haul.

Finally, looking ahead, we will need to consider the difficulties involved in shifting our collective perception of what it means to win in the context of militant, confrontational contract campaigns. Labour management cooperation schemes have significantly shrunk our collective understanding of the possible such that we have become habituated to asking for and accepting crumbs. Even worse, we have come to mistake these crumbs as real gains for workers even while workers’ power has been steadily shrinking under neoliberal capitalism. Meanwhile, pursuing an overtly antagonistic encounter with the employer necessarily involves not only intensified labour militancy but also unleashes heightened employer hostility as well. How do we navigate and lead a militant labour movement that fights–for the long-haul–beyond any individual campaign? Insofar as we are committed to shifting the balance of power in our institutions, we will need to articulate new horizons beyond those that have been delimited by the collective bargaining process.

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Winning a Bargaining Unit for All Graduate Workers

by

Logan E. Mann

/

July 3, 2023