Lessons from the New School Strike

by

Andy Battle

July 3, 2023

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

On last year’s struggle at The New School and what militants can learn from it

inquiry

Lessons from the New School Strike

by

Andy Battle

/

July 3, 2023

in

Correspondences from the Upsurge

(Book)

On last year’s struggle at The New School and what militants can learn from it

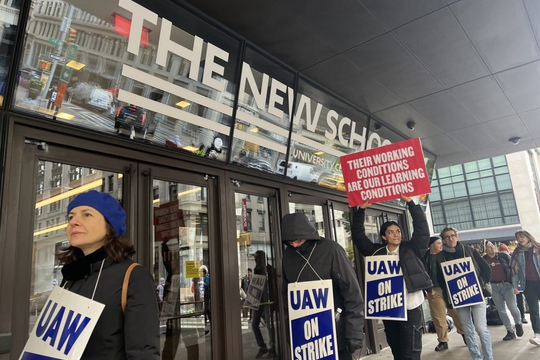

On December 10 of last year, part-time faculty at The New School concluded what is thought to be the longest part-time faculty strike in US history. On one level, the strike has been a success. It marks the fruition of several years of patient organizing along principles that respect and harness the energies of ordinary, rank-and-file union members. It has tested the power of that approach in an event that helped coalesce a fragmented majority into a distinct class of workers capable of acting in concert at a scale significant enough to shape the institution. The act of mounting the strike called forth new political connections between part-time faculty working at various institutions throughout New York City and between those faculty and the students they teach. And it has warded off the efforts of a particularly cynical group of administrators who sought to break the union as part of a project to eliminate the power of faculty, itself part of a broader effort to reorient the school as a moneymaking scheme.

At the same time, the concrete results of the struggle, now formalized in a contract that has been ratified by a large majority of members, suggest an essentially defensive effort that may merely slow the trend whereby university teaching becomes an increasingly unfeasible strategy for living, particularly for younger workers flailing at the perpetually exploding cost of living in expensive cities like New York. What are we to make of this contradictory situation and the politics that produced it? Has adjunctification—the decades-long effort by university administrators to reduce compensation and dilute faculty power by offering only part-time, profoundly insecure terms of employment—generalized to a point where it cannot be addressed in a substantive way within the terms of individual contracts at discrete institutions? Put another way, can collective bargaining as presently institutionalized in the United States produce anything like an acceptable standard of living for the group of university teachers who constitute an ever-growing majority?

Like all institutions, The New School is in some ways typical and in other ways unique. Founded in 1919 as an alternative to hidebound elite institutions, the school has long harbored a reputation as an institutional home for the cultural, political, and artistic avant-garde. It has been avant-garde, too, in its commitment to treating the majority of faculty as independent contractors, paid on a per-course basis with few benefits and little guarantee of secure tenure. Today, 87 percent of instructors are part-time, a figure that rises above 90 percent in some divisions. In this way, The New School, an uneasy accretion of distinct revenue centers staffed for the most part by a layer of administrators overseeing armies of poorly-paid, insecure adjuncts, prefigured the model to which more conventionally structured institutions now aspire. The present administration sought to push this logic to its extremes by taking an extraordinarily aggressive stance in last year’s contract negotiations. The goal, it seems, was to crush the union as a body capable of intervening on behalf of the values of faculty, which prioritize the interests of students conceived broadly as human beings rather than “customers,” as the school’s pricy union-busting lawyer absent-mindedly described them in bargaining sessions. These values—the academic version of workers’ control of production—threaten to interfere with the administration’s strategy to transform the school’s radical ambience into dollars.

This strategy, as well as the composition of the workforce and of the student body, are shaped by the contradictions of the world’s most expensive city, whose role as a funnel for idle capital from all over the world drives living costs to extremes. Though its vitality has been seriously eroded by the dulling power of money, New York still sits, at least for an American city, at the forward edge of art, commerce, politics, and intellectual life. That so many artists and intellectuals wish to be here and are willing to find creative ways to remain explains how The New School can find anyone to teach at the extraordinarily low wages around which it has built the institution. The school draws a student population attracted to what remains of New York’s unconventionality and who dream of dedicating themselves to art, to city life, to social transformation. For The New School, the dynamics of contemporary New York City represent both the product—what must be leveraged, packaged, and sold—and the major constraint on how a relatively young institution, whose small endowment and dearth of revenue-generating centers the so-called “hard” sciences leave it especially dependent on tuition. This tension can also be seen in the way that its market niche – tolerance for nonconformity in research, curriculum, and pedagogy – limits grant funding and produces alumni who tend not to be fantastically rich, thereby undermining its own market viability in an arms race of escalating costs and a relentless scramble to shove them off onto students (in the form of tuition and debt) and teachers (in the form of punishingly low wages).

If The New School represents a perpetual, scrambling emulsification of these social ingredients, the strike represents a moment where this mixture began to break down. Working on the terms of a contract settled in 2014 and haphazardly extended during the pandemic, a period during which teachers received no raises as the cost of food and housing surged, part-time faculty found themselves increasingly unable to make the equation work in even the most basic way. A not-insignificant number have been driven out of New York City entirely, teaching online or enduring marathon commutes to retain the jobs they were trained for and in many cases love. Unevenness in circumstances across part-time faculty both exacerbates the crisis and complicates efforts to consolidate disparate needs into a coherent set of demands. The escalating cost of living and the gradual erosion of what passed for a social safety net in the United States means that younger faculty, who are less likely to have secured stable long-term housing arrangements, to have external sources of income to continue teaching for virtually no money, or to have avoided severe indebtedness to earn their own degrees, are often in a more dire position than their elder colleagues (this is not to minimize the drastic situation in which older part-time faculty often find themselves, particularly around maintaining access to health care as they move into a period of life where they are more likely to need it). The situation is generally worse for young part-time faculty of color living in a world where white supremacy means they are much less likely to have family resources on which to fall back. For younger academics, a basic sense of security around food and housing appears essentially as the result of a lottery. There has been a decoupling of any connection between what one contributes to the well-being of the students and the institution and one’s ability to have a life that is not debilitatingly stressful, a life that does not feel out of control. The consequences for students are real—once they have resolved no longer to work for free, teachers cannot afford the hours or the creative energy that produces the experimental curricula on which the school sells itself. I remember once spending a Christmas Eve grading student essays for a course (at another institution) that paid $2,900 for the entire semester. I will never do that again because it is a form of self-abuse.

The task of the union was to cohere these uneven realities into a program of demands while mobilizing a socially and geographically disparate membership. It had to communicate the realities of part-time teaching to both students and full-time faculty, and ultimately, mount a strike that would profoundly disrupt the university’s ability to deliver on what it has promised students—promises, it has now been demonstrated, that are made on the expectation of vast quantities of unpaid labor extracted from their teachers. This effort was facilitated by a strategy that adheres roughly to what has been called the rank-and-file approach, which respects and harnesses the energies of a broad swath of the membership rather than lodging decision-making in a small coterie of professionals operating at a remove from the day-to-day life of the workplace. One example of this principle is the union’s commitment to open bargaining. This approach to formal negotiations with management encourages transparency, accountability, and participation, contributing ultimately to the forging of a broad collective capacity. These attributes proved necessary to pull off a successful strike in the face of an administration whose aggressiveness even shocked seasoned observers, not to mention those who believed that the present administration, gauzy rhetoric notwithstanding, shared their commitment to The New School’s history of radicalism and experimentation in the service of social transformation.

It is clear that the administration did not expect the torrent of opposition that met its refusal to offer part-time faculty anything and its attacks of those full-time faculty who canceled classes in solidarity with their part-time comrades. Support from this relatively privileged minority helped, but what in the end broke the dam was the outpouring of tireless, militant, and creative solidarity from students themselves. They were the primary engines of joyful energy on the picket line and, when the strike appeared to be heading towards a potential stalemate as the end of the semester loomed, students mounted an occupation of the school’s University Center. Within hours of this event, the administration made its first real concessions. The occupation both reenergized the strike—during this period, a new chant emerged, bouncing off the buildings on Fifth Avenue: “one day longer / one day stronger!”—and created a new kind of social space that permitted new encounters and suggested the possibility of a self-managed university. The demands that ultimately emerged from the occupation envision a radical transformation of the university into an institution dedicated to teaching and learning under worker and student control.

Still—for all the promise of the occupation; for all the will, exhilaration, and strategic acumen that forced the hand of a wildly recalcitrant administration; for the sheer gargantuan effort poured into composing a directed movement out of a previously fragmented body—one is struck by the disparity between this taxing achievement and the material results of a contract that has been approved by 97 percent of the membership. That the efforts of the bargaining team won near-universal assent testifies to its success in remaining in touch with the membership and suggests that most members shared the feeling that this contract represents something like the maximum that could be achieved given the balance of forces as we moved towards the winter break. A comparison with the highly contentious vote that ended the strike across the University of California system—a struggle conducted, it should be noted, at a vastly larger and more complicated scale—reveals, by contrast, a New School group that remained cohesive throughout the strike and its settlement. At the same time, the question remains—given the remarkable volume of support we enjoyed from students, from other faculty, from the press, and from the public, could we have stayed out longer? Did we concede too much too soon? There were many moments during the strike where the situation looked to be at an impasse, moments when a kind of defeatist realism took hold among portions of the membership. By pushing through these moments, by refusing to accept the apparent limits of what seemed possible, we were able to expose so-called realities—whether financial, political, or organization—as profoundly contestable. This awareness in turn raises questions about how to gauge the balance of forces in a rapidly unfolding conflict—how to predict, in the thick of a complex and demanding struggle, the direction it will take in one day’s time, three days’ time, three weeks’ time. It also raises questions about the relationship between a realism that correctly judges present circumstances and a speculative instinct that can apprehend how those objective circumstances are shattered and reassembled by the force of collective action.

But the fact that the material improvements secured by this contract are meager enough that many will have to leave the profession raises other questions. What if a union does everything right in a localized struggle conducted according to the legal parameters of collective bargaining and the result remains essentially defensive? What if all that can be achieved is a moderation of the worsening of pay, benefits, and working conditions, allowing those who have managed to secure some kind of accommodation within this city—those who tend to be older, wealthier, whiter—to hang on another year longer? What if principled militancy at the local level is not enough? The reality is that the abuse of the majority of the teaching workforce is the key to the modern American university—the practice that structures all others. Anything else is just PR. No group isolated on this or that campus can meaningfully alter this reality. The laws of competition are personified in those who control universities, and through them injury must fall on the fortunes of any school that bucks the trend and pays teachers enough to live on because it is the right thing to do. This reality reared its head in the New School strike, when many union members found themselves unsure to what degree they should accept the school’s cries of poverty relative to its local counterparts. Even the bargaining team found itself compelled to accept that the uneven terrain creates real limits for teachers at this or that school. This concession to the realities of the market has resulted in a contract that will see New School teachers paid much less than their counterparts at New York University, ten blocks to the south and represented by the same union but a universe away in terms of revenue.

All strategic decisions by unions of part-time faculty should therefore be made with two related principles in mind. First, individual universities as currently structured cannot accommodate a living wage for the vast majority of their workforce. Second, no struggle conducted within the boundaries of localized bargaining units can make a durable dent in this reality. Spreading awareness of these principles should be a major goal of the academic labor movement. This will take a concerted educational effort, massive disruption of the existing state of affairs, and the amassing of coalitions at scales large enough to provoke the massive disruption that alone can trigger a transformation. There will be casualties on both sides. The appetite for such a transformation is limited at present, in part by the ways that individualized struggles to carve out combinations of wages, health benefits, and outside financial support sediment themselves in ways that tie the well-being of individual part-time faculty to the success of the university in its present form. The collapse of American higher education, which is already in motion, and its reconstitution along new lines is a given. Will part-time faculty be the passive victims of this process or its drivers? What would a decentralized, worker and student-controlled university look like? What would happen at a university that was no longer selling a product, namely access to particular labor markets? How could such an institution survive, in material terms? The struggles of the past, right here in New York City, furnish some resources. And such discussions are taking place in scattered quarters across the world. Thinking at this broader scale is imperative if we are to do anything besides clawing for slightly bigger pieces of a fruit whose decay is making all of us sick.

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

author

Andy Battle

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

UCU Democracy

by

Royal Holloway Early Career Academics

/

March 19, 2023