The only polemic left in the art world is worker power

by

Steff Huì Cí Ling

August 22, 2025

Featured in Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture (#24)

On culture worker organising in Vancouver and beyond.

inquiry

The only polemic left in the art world is worker power

by

Steff Huì Cí Ling

/

Aug. 22, 2025

in

Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture

(#24)

On culture worker organising in Vancouver and beyond.

I worked as a freelance art critic (among way too many other things) for about eight years between 2012-2021 and then I started studying the labour economies of the art world. If my criticism had any currency among artists and art workers as critical appraisals of art, then with my combined experience as an art critic, training as a labour sociologist and commitments to class analysis, I want to express my current view that the only polemic worth doing within the art world is worker-to-worker organizing.

For art workers, one of the main challenges for organizing is identifying who we can count on to have our backs in a labour struggle because a big part of working in the arts is having trust issues. So, I asked my comrades to share how we got started organizing together, what were some barriers to organizing we faced, and any words of solidarity to art workers who are just getting started with labour organizing.

We are freelance and unionized art workers in solidarity with each other’s struggles for better working conditions. Some of us are unionized with IATSE Local B-778, the Arts and Cultural Workers Union (ACWU) which represents a few galleries in Vancouver. Many of us are not unionized, some of us started organizing as union members then our contracts ended, and some of us are both union members who are also freelancing. The composition of our employment, and therefore our relationship to the union, is always changing or subject to change. Every unionized worker is potentially also a freelancer, and every freelancer is also potentially a unionized worker. So, for us, it has been a process of making material and political sense of these struggles across union and non-unionized contexts and connecting our organizing beyond the labour movement in solidarity with land defense, anti-gentrification, the struggle for safe supply, migrant justice, and Palestinian liberation.

The responses I received energized me to consider why we collectively emphasize forming socially authentic relationships on the way to the meetings, town halls, teach-ins, rallies and picket lines. Before hearing from our small and growing cadre, I wanted to identify some notable conditions of the art world’s labour market and clarify that the so-called “art world” needs to be understood as completely distinct from its labour market. My preamble intends to bring into full relief the words of my comrade art workers in Vancouver, Canada, as a slice of practical resistance to these conditions by expressing alignment with working-class politics. Responses are lightly edited, published in their received format and are anonymized with respect to workers in active campaigns or bargaining.

Preamble: The art world vs. the art world’s labour market

To begin, it’s critical to problematize some of the conditions of being in the “art world” as conditions shaped by the choice of circulating in the art world’s labour market.

We might like to consider how feelings of social exclusion from certain cultural spaces or cohorts are symptomatic of being part of a labour surplus that annually refreshes with each graduating class of every contemporary fine arts program. Being part of the art world’s labour surplus incites an extremely tacit sense of competition amongst a chronically underemployed section of a disidentifying working-class. Many art workers do not recognise each other as workers, so the alienation that comes from participating in the circulation or production of art, and the attendant competitiveness required to stay close to opportunities for participation, are experienced as personal shortcomings, or conversely, sources of self-worth.

Why circulate in the art world’s labour market/emotional rollercoaster if the sector is defined by a shortage of jobs and an excess of labour? Because we like art, some may even love it (or a version of it that is legitimised by the very institutions and practices that we seek to be gainfully employed within). Therefore, we accommodate exclusion as a social and economic practicality of having a relationship to art. In other words, another condition of circulating in the art world’s labour market means choosing art, or working in the arts, over meaningful or equitable social relations. In other words, art workers may internalize the classist logic that exclusion is necessary to maintain circulation in this particular labour market. Those social relations may have been what we associated art with in the first place, but as an art worker comrade writes in their response below, liking art is part of our humanity, not tantamount to throwing your comrades under the bus. However, from a workers’ standpoint, the art world seems to necessitate doing so in order to circulate in its labour market.

Political posturing

Despite what curatorial statements claim in the exhibition copy or the grant applications, in the art world, the social program is more one of mutual back scratching than of mutual aid or community safeguarding. After all, exhibition copy is an engagement technology in the sector’s numbers game. Public funding is a loan that is repaid with the cultural commodities produced by art workers to conform to the state and private sector’s cultural mandates. We should not draw our political identities or agendas from the discourse or methods produced in the art world, but it has been known to happen because of the art world’s tendency to cannibalize anything of political purpose and render it as merely progressive optics.

Proximity to political activity is occasionally part of the grift, so if we are faced with inconsistent political practices, it can exacerbate the trust issues instilled by the art world’s profound insincerity. In our organizing, we are not aiming for everyone to have exactly the same or perfect politics, but if we can correlate an institutional curator’s publicly pronounced solidarity to an upcoming group exhibition thematic, then this managerial character is not a comrade, but a WISH (well-intentioned shit head). It is frankly a security risk to invite anyone and everyone to worker gatherings or meetings. Organizing in the art world’s labour market carries a very high risk of potentially involving someone in your workplace struggle who is, however consciously or unconsciously, capitalising on appearances of allyship or political engagement.This makes public-facing organizing or advocacy highly susceptible to suspicion of grifting, and vulnerable to grifters. Aside from the grifting, we very simply don’t want well-meaning managerial types to know that workers are getting together and talking about their working conditions. From what we’ve seen at various bargaining tables, there is a union-busting playbook, and these WISHES use it. As a result, our base-building has been gradual, and low-key, but not exactly secretive. Art workers socialize in village formation, so the workers who want to throw down will find each other!

Slices of practical resistance

The process of base building in any sector is the process of confronting the deeply anti-social conditioning of the non-profit arts and cultural sector, which in turn, has shaped the conditions of the labour market, and therefore our approaches to labour organizing.

As art workers organizing as a part of the broader labour movement, it has been critical to establish our shared political standpoint as workers, reflected through our respective standpoints as racialized, gender non-conforming, migrant students, parents, and youth. We organize as members of the working class, name settler-colonialism as a labour issue, and endeavor to build art worker power within our section of the labour movement — and through these principles, the conditions produced by circulating in the art world’s labour market are dynamics we never want to replicate or find manifesting in our organizing.

We are motivated to do the work of building genuine relationships premised on sharing struggle, creative intellect, and the trust necessary to agitate against the art world and its elites - an entity that should be understood less as a multinational community for the display of appraisable art and culture, and more as a sprawling abstraction of extractive power and economies

Leave a place better than you found it

How did we start organizing together, and what are some things that have helped get you motivated and connected with your art worker comrades?

Like many others, I turned feelings of rage towards previous toxic working conditions into passion for a more productive and worthy cause. As a fairly new addition to the workforce, too, I had personal relationships with a handful of up-and-coming art graduates who would inevitably follow my example. As the saying goes, “Leave a place better than you found it.” This is my best attempt to do so.

What were some barriers to organizing that you felt were overcome?

A common barrier that comes up when speaking to my community is lacking that personal connection with our comrades outside simply being in solidarity. Taking the initiative to meet up with them and getting to know them outside this work has been both refreshing and fulfilling, becoming the fuel that keeps me coming to organizing events. In the end, we’re all just humans who crave friendship.

Would you like to share any words of solidarity to art workers in faraway places?

During challenging times like these, community is our most valuable asset. Fight for each other and take care of each other. We’re all we’ve got!

Make comrades out of co-workers

It all started with organizing the workplace I found myself in and making friends and comrades along the way. Everything is driven by struggle and snacks. That’s what solidarity is made of. From making comrades out of co-workers through unionizing one workplace, our small site of struggle became a catalyst for mutually supporting other workers who were collectivizing their struggles at other workplaces. This larger collective of collectives was the rank and file of our Arts and Cultural Workers Union local. At this level and collection of workplace struggles, there was a recognition that all of our struggles are interconnected and that gaining more collective power requires more collaboration and coordination for the combative politics needed to face the larger contradictions that emerge while escalating our fight against capitalists of all scales.

One of the barriers to organizing that I felt we overcame was our reliance on the union’s bureaucracy. The belief that the “union” will spearhead the work instead of the workers is one of the myths that we needed to overcome if we wanted to win OUR battles. No one is going to liberate you except yourself and your trusty comrades. It may seem like there is no escape from capitalism unless we sell out. No one likes a sell-out. We are keeping tabs. Of course, consent and care and all that, but capital will crush us all unless we organize to crush them.

You will likely run into naysayers who will spit on your work as art and cultural workers organizing other art and cultural workers. Take their name and number and make them pay later. They are probably projecting their own bourgeois tendencies and class prejudices on your working-class organizing. Not everyone is your friend based on their self-proclaimed camp and/or political identity. Find class-traitors and working-class people who will fight and build for the long-run. And remember, the cultural work you do to keep working-class organizing alive is all part of class struggle. Organize to win!

Build solidarity muscle

How did we start organizing together, and what are some things that have helped get you motivated and connected with your art worker comrades?

I study labour economies in the non-profit cultural sector as a PhD student and my research began by conducting an art workers’ inquiry. I became good friends with one of the respondents of the inquiry, who is a unionized art worker and a comrade on many other fronts. We organized the first art workers’ town hall together and personally invited everyone we had ever had a conversation with about their working conditions in the arts. Having something to work on together and pulling off a decent attendance without any social media was a really encouraging testament to the latent labour consciousness among our friends and contacts. A handful of art workers from that town hall are the comrades I have in this struggle today.

What were some barriers to organizing that you felt were overcome?

I think there are times when we get hung up on who “counts” as an art worker. I think everyone has both ideas and questions, so something that has cleared up for me is that an art worker is not necessarily specific to occupation, but economic status — someone who necessarily exchanges labour power for money in the production, circulation and consumption of art and culture. This definition functions to exclude elites or trust fund kids who have no qualms with low wages and include freelance workers who are in exploitative but not waged scenarios. In organizing with and around ACWU, the recent certification of a FlyOver, a flight simulation facility in the tourist district also provides a sobering definition — someone employed in the arts, entertainment and recreation sector. It’s also the union’s largest bargaining unit.

Would you like to share any words of solidarity to art workers in faraway places?

Art workers belong in the working-class fight alongside education workers, care workers, postal workers, and workers in heat for their solidarity with Palestine. If we take these labour struggles seriously, then we should fight for achieving better conditions of our own too — build solidarity muscle!

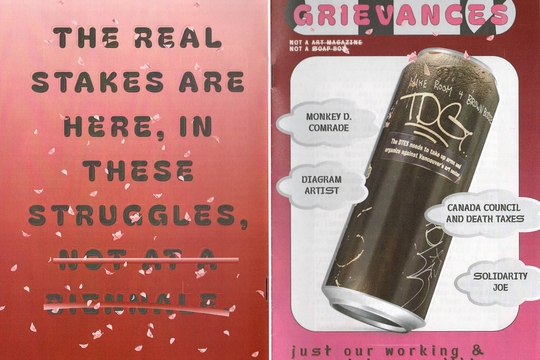

The real stakes are here, in these struggles, not at a biennale.

How did we start organizing together and what are some things that have helped get you motivated and connected with your art worker comrades?

I became involved in organizing after my former workplace (an art gallery) unionized and became an unofficial gathering place for art workers in the neighbourhood. It feels exciting to be part of a group that is just starting out. We are getting to know each other and figuring things out on the fly. At the same time, some of us have more organizing experience and are able to think more concretely about strategy and logistics. I’m happy to be learning from and thinking alongside these comrades. Also, working in the arts, we’re used to feeling like our jobs don’t matter: not just because we are underpaid and underemployed and our families don’t understand what we do, but also because the art world breeds nihilism. My comrades have helped me realize that there’s a secret third option between ‘believing in your job’ and all-consuming cynicism: actively work toward better conditions in the sector while strengthening our ties to related struggles (tenant organizing, decolonization, etc). The real stakes are here, in these struggles, not at a biennale.

Would you like to share any words of solidarity to art workers in faraway places?

If you’re like me, you probably started working in the arts because you love art. This is a core aspect of your humanity. Don’t let the art world—the world of commodities—take that away from you!

You’re just getting to the place you need to be

It’s been 5 years since I started organizing animation workers with IATSE Local 938. Coming to the first Art Workers’ Town Hall, and seeing new organizers find their sea legs was a reminder of how much I’ve learned, and how hard it is to condense into ~300 words, but I’d like to try.

Organizing is workers talking to each other about building our power, and it’s an organizer’s job to get their co-workers comfortable enough to do that. It’s easy to get lost in all the ways you could get everyone comfortable, especially when you’re just getting started. And you probably will. Think of it like a first pass. If you and the other organizers can’t talk openly & honestly, how do you do it with a co-worker you walk by on your way to the bathroom?

But at some point you have to actually talk to Bathroom Co-Worker. A good way to start is to find out their name and stop thinking of them as “Bathroom Co-Worker.” Start building a relationship. Again, you’re just getting to the place you need to be. But you can’t lose sight of that. Because you’re gonna have to do it again, and again, and again, until all your co-workers and you are talking to each other about building power.

If that seems like an over-simplification, it’s because it is. Each of those conversations is going to be its own entire experience, and some will be really terrible. But most of them will probably be good. And the more conversations you have, the more good ones there will be, and the faster you’ll get to the important part: building and using your power as workers. At that point, hopefully some workers will come to you asking “How do we do that?” and you’ll be in the same position I am. And then you can struggle to put all the knowledge you learned into a 300-word paragraph. And that’s a whole other challenge.

author

Steff Huì Cí Ling

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

South London Bartenders Network

by

South London Bartenders Network

/

Oct. 7, 2020