A Road Map for Branch Activists to Organising a Successful Marking and Assessment Boycott

bulletins

A Road Map for Branch Activists to Organising a Successful Marking and Assessment Boycott

by

The University Worker

/

March 30, 2023

A contribution to the debate on the MAB

Notes From Below are publishing this guide to the MAB to encourage discussion and debate on how to organize it, however, publication does not imply an endorsement of any faction within the union.

A Road Map for Branch Activists to Organising a Successful Marking and Assessment Boycott

By: Katy Fox-Hodess, David Harvie, Mariya Ivancheva and Mark Pendleton

‘All branches should be using picket lines to organise and plan for a summer [marking and assessment boycott’. – Joe Newman and Roberto Mozzachiodi, ‘Notes on a Marking and Assessment Boycott’, Notes from Below, 20 January 2023.

The future direction of our two #ucuRISING disputes – the Four Fights and on USS pensions – is currently uncertain – in dispute, we think it’s fair to say. What happens next will depend on the outcome of various meetings and consultations. We don’t want to comment here on how our union arrived at this point, nor on what steps we think it (we) should take next. Instead we want to offer some very concrete organising recommendations regarding a summer marking and assessment boycott.

In another article some of us argued for a summer marking and assessment boycott in the present dispute(s) and also that we should target student recruitment, via strikes or other actions timed to coincide with open days and Clearing. The situation has clearly changed in the three months since we published that article. But if we – UCU members working in universities – decide to proceed with a summer marking and assessment boycott, then organising for it needs to start now. In fact, organising for a successful summer MAB should have started one, two months ago, on pickets lines and in other strike-related spaces – as Newman and Mozzachiodi argued. Whatever members decide regarding the current disputes, however, we have no doubt that it will not be too long before we are forced again to take industrial action, in which case we would argue again for the use of a marking and assessment boycott (alongside other tactics) – but stress that, like all tactics, an effective MAB requires careful preparation and organisation.

In what follows we provide some concrete recommendations on how the national union, branches and department level activists can organise for a successful MAB and unpack some of the lessons, drawing on Newman and Mozzachiodi’s article and our own experiences with a MAB at University of Leicester and University of Liverpool in 2021. We have written the article under the assumption that the MAB targets summer exams and coursework.

Preliminaries

The most important commodity produced by the university is the credentialised graduate. The only way one gets access to this rather strange commodity of a degree – expensive yet sold as essential to many school leavers – is admission to a university degree programme. We use these words with careful intent. Those of us who work in universities are typically motivated by other values: education as a social good, a desire to share wisdom with others and/or to push the boundaries of knowledge. But the vice-chancellor of the modern public university – dominated by the logic of finance and in which metrics map onto money – is motivated by the necessity of maximising student recruitment and graduation. The most effective industrial action is therefore action that disrupts universities’ ability to recruit and graduate students. However it is only effective if we can overcome the conflict between this disruption and the motivations for UCU members to do our jobs.

We believe that there is much that our national union can and should do to support a MAB. In fact Carlow Street prepared a helpful FAQ briefing on this in May 2022, updated in February this year. But we recognise that UCU’s resources are limited and we – UCU members and, in particular, elected officers, elected members of NEC and its subcommittees, congress and conference delegates – already make many demands of its paid employees. So while there is a central role at HQ in terms of coordination of organising, our collective success as a union will, as always, rely on member participation.

What is a MAB?

In principle a MAB is very simple. Members refuse to carry out any work that is associated with student marking and assessment.1 For teaching staff (academics) the work that we should refuse includes:

-

setting examinations and other assessments;

-

invigilating examinations;

-

marking examination scripts and other assessment;

-

providing any form of summative (grading) or formative (feedback) assessment;

-

second-marking or moderating examination scripts and other assessment;

-

attending examination boards and panels, moderation or standardisation meetings;

-

carrying out assessment activity on Turnitin or the Learning Management System/Virtual Learning Environment;

-

sharing assessed material amongst colleagues.

Staff should not ‘mark-and-park’ assessments, that is, mark scripts or assignments, but refuse to submit then, since once any marks are committed to paper or computer (even if a private computer in the person’s home), these marks become the legal property of the employer.

For administrative (professional services) staff this includes: administering any of these processes.

Here it’s worth referring again to UCU’s advice, available here.

A MAB can be effective because it prevents university bosses from graduating final-year students and from progressing non-finalists to the next year of their studies. As we wrote in January:

Universities in England are responsible not only to their fee-paying students, but also to the Office for Students, creating additional pressure to deliver degrees in a timely manner and thereby amplifying our structural power during the summer marking period. Every registered provider of higher education in England must report to the OfS, demonstrating its financial sustainability, the ‘quality’ of its academic provision, that it is delivering ‘positive student outcomes’, and so on. Amongst these indicators are student progression and graduation rates and in September 2022, the OfS announced ‘new expectations’ of universities, ‘set[ting] minimum expectations for the proportion of students on higher education courses who continue on their course, graduate, and go on to further study or find a professional job’.

As we note in our previously-mentioned piece, UCU’s last major victory, in 2006, was the result of a marking boycott. The struggle against mass redundancies at University of Leicester in 2021 was ultimately unsuccessful, but arguably the MAB initiated as part of that struggle was the most effective tactic in Leicester UCU’s arsenal, the only tactic in fact that forced bosses negotiate. We can only speculate, of course, but had the MAB been better observed by UCU members, we might have forced more concessions. And writing of the struggle against mass redundancies at Goldsmiths in 2022, Newman and Mozzachiodi say:

It is worth stressing that after 37 days of strike action, we were only able to delay the redundancy process. Until the MAB began to bite, our employers had offered no tangible concessions in negotiations.

However we also need to recognise the limited and uneven effectiveness of the 2022 summer MABs at several branches, called as the disaggregated dispute that year was winding down. While some branches achieved some positive outcomes - such as the spine point adjustments at Sheffield and vastly improved parental leave provisions at UAL - these were partial, and it is not clear how widespread participation was at the branches participating.

How can a MAB be effective?

While it is helpful to ensure that activists have the correct information whether legal or otherwise about a MAB, what we need now from our national union is ongoing training to help branch level activists understand what they need to do to organise an effective MAB on the ground. [Just as we finished writing this piece, Carlow Street announced three one and a half hour training sessions open to all members. We hope as many organisers and activists will register. You can do so here:

However, our national union can’t organise a MAB itself – that will always come down to activists embedded in branches. To understand better how we can organise around it, we use our own experiences from different campaigns and pull what we deem to be useful resources from across the union. We believe that ongoing training and support could helpfully focus on three key areas:

1) Mapping. While strike action typically involves all members, a MAB is much more targeted, involving only workers with marking and assessment responsibilities. The best way to maximise our power on the ground, then, is to focus on shoring up support among members with summer marking and assessment responsibilities, as well as recruiting non-members with summer marking and assessment and responsibilities associated with Clearing. (We say a little about bolstering support in point 2, below.) UCU activists in departments can use their departmental workload models to map out (1) course marking schedule with exact start and due dates and (2) staff with responsibilities to mark , or administer marking, on these courses, whom they can approach to join the union and/or participate in the MAB (more on this below). An additional useful mapping exercise would also focus on identifying staff and PGR students – whether UCU members or not – whom the university managers would likely try to recruit as strikebreakers in the event of an MAB. Again activists need to approach these colleagues, seeking to gain their support. (We say more about support in point 3, below).

Helpful tips for doing this: work in a team with other activists in your department to identify potential participants in an MAB. Divide up the list of names and decide who will be talking to who – good rule of thumb is for people to speak to others in similar positions (i.e., casualised staff with casualised staff, PGR’s with PGR’s, academics with academics, PS staff with PS staff) because they will be more likely to be able to respond to role-specific concerns credibly. In some instances, programme managers or administrators (whether academic or professional services) will be willing to share information on which staff are responsible for marking and assessment on which modules. If you are in a large department, it will be helpful to put this information together into a shared activist spreadsheet such as the one in this downloadable template to keep track of who you are speaking to and whether or not those conversations have happened yet.

2) Persuasive conversations (including inoculation). Persuasive conversation training is essential to any organising training. While email and text tools are helpful ways to disseminate information and mobilise a strike vote, meaningful participation in industrial action comes about through face-to-face conversations in the workplace, both one-on-one conversations and department- or workgroup-level union meetings. Through practicing engaged responses to short, typical scenarios of staff members asking questions, raising concerns and expressing misgivings about a MAB, branch level activists develop greater confidence in organising. This aspect of organising training is primarily ‘horizontal’ – simply creating spaces for activists to role play these organising conversations together and talk through helpful and unhelpful responses is at the heart of this (bespoke MAB organising training materials, including an organising guidance document for activists, practice scenarios and a short train the trainers document on how to use these can be downloaded through these links).

Note that persuasive conversation trainings should incorporate an understanding of what unions call inoculation - that is, preparing members for the likelihood of negative blowback from employers, and letting them know in advance that this will actually be a sign that the action is hitting its target and, just as importantly, that the union will back them up if this happens. Inoculation helps build trust and confidence – the most important foundations of successful organising. In the case of a MAB, we know there is a high likelihood of employers attempting to take full deductions for so-called ‘partial performance’, so members need to be prepared for that likelihood ahead of time and told how the union will respond to support them. We can draw on the expertise of branches, such as at Queen Mary, University of London, that have already experienced this and learn from how they have navigated an organising response.

As this point we must recognise that, as we write in March 2023, many members are feeling burnt out from taking weeks of strike action this year already, as well as from the acrimonious climate of debate within the union. It’s important not to paper over this in organising conversations. Good organising requires us to genuinely listen to one another’s concerns and to validate and empathise with whatever people are feeling at this or any other juncture. But what makes an organising conversation different from an ordinary conversation about work or the union is that an organising conversation then helps move people to take action. We can do this by making clear how an MAB is different from a regular strike and why we believe it will provide us with exceptional leverage above and beyond what term time action can deliver. (See our January 2023 article for more on this point.) Understanding the additional leverage that an MAB will provide can help to give people the confidence to dig deep and find the resources to take further action this summer.

3) Strike logistics and support (sustaining the strike). The far greater pressures placed on a smaller number of activists in a MAB than in regular strike action necessitate the building of supportive structures. Shoring up support in this case could mean a number of interrelated practices. Those on the frontline of MAB need to be offered (1) enhanced and quick access to the strike fund; (2) case workers to explain the risks and their rights, and to mediate with HR in case they are approached and intimidated, and potentially working for collective bargaining strategies rather than individual cases [see Goldsmiths]; (3) a peer support group to not feel alone and alienated especially in departments where they are not a majority (especially STEM studies and HASS departments where even if union density is higher, management is strike-hostile). In particular, activists could consider building up local funds (including at the department level) to replace the full value of pay lost by colleagues during an MAB; activists could organise sign-on letters for workers to indicate that they will refuse to take on any marking and assessment duties during the strike (either additional duties or duties assigned to strikers); activists could plan regular dept or branch level social activities to recognise and support the strikers; and so on. It would be very helpful to arrange some webinar type events with activists from branches that have confronted these challenges already in MABs to see what we can learn from them.

The challenges of sustaining a MAB

Sustaining effective industrial action and winning victories is never easy – and the MAB is no exception.

Apart from examination boards and panels, marking and assessment is almost always a highly individualized activity. A university teacher generally marks work at home or in their office, i.e., on their own. Their refusal to perform this work therefore feels like a lonely refusal, isolated and isolating. The visible, visceral solidarity of the picket line is absent. This is even more the case with casualised workers, who are not part of certain faculty meetings, collective decision making, and often hot-desk without designated office spaces. The individual nature of this refusal is further compounded by the fact that not all teaching staff mark at the same time: exams take place on different days, coursework has different deadlines. Even during the same marking period (roughly May–June for Semester 2) not all teaching staff necessarily have marking duties. Thus, the burden of maintaining a MAB is likely to fall on a minority of teaching staff and an even smaller minority of professional services staff.

The main challenge here then is to overcome this isolation. Practically this means that branch organisers and activists must first identify those staff who do have marking and assessment duties when the MAB is scheduled and second support these staff – morally, politically, financially – such that they are able to bear this burden.

Such support might include:

-

Dedicated fundraisers and suggested proportional salary sacrifice among those not on MAB such that those engaged in the MAB do not lose any more income than others and have a direct and quick access to the national and local fight funds.

-

Positive and encouraging political messaging recognising that those engaged in the MAB are the people on the frontline and deserve everyone else to be with them and support what they are doing.

-

Dialogue with student representatives and students about the significance of the MAB to the strike and the motivation of lecturers to engage in it: not without care to students, but with care that those students who go on to the world of work are not faced with the same diminishing labour rights and worsening labour conditions and discrimination that faculty in HE face day in day out.

-

Political messaging and one-on-one conversations to dissuade other staff from strikebreaking and/or ostracising the MAB faculty locally.

-

Practical support: those on strike in general but those on MAB specifically need to know their rights and the risks of being in this position, as well as the resources available from UCU to support them through case work if conflict emerges with their line managers.

-

Moral support: shoulders to cry on, ears to listen on demand, advice on how to respond to cajoling and bullying from bosses. This should occur as one-on-one and also small support groups, within and across departments.

-

Data on the participation levels in the action. Some departments and individuals holding the line on the action, may need evidence that they are not the only ones shouldering the action and that the action is having an effect. This is especially the case when managers will be routinely broadcasting to the staff body that the action is having little to no effect. A good way to head-off these anxieties, is to collect data on participation as early as possible.

Managers are likely to respond aggressively to a MAB. First, as we saw with Queen Mary, University of London, there is the possibility of 100% pay deductions for those staff who refuse to mark student work. It’s essential we prepare members for this possibility and explain how the union will respond if it happens – either with escalation and/or with financial support for targeted members. What’s also important to emphasise here is that university bosses never play nice and that if they do withhold pay (or threaten to) this is a sure sign that the MAB is hitting its target.

Managers will also act aggressively to fill in gaps in student records that exist because of the MAB. We can expect them to resort to a variety of tricks. These include:

- Seeking to outsource marking, i.e. employing labour from outside of the university. Although we’re not aware of this actually happening thus far, we expect that the more ‘entrepreneurial’ or ‘innovative’ VCs will look overseas for cheaper and less unionised labour. We know that bosses at Queen Mary, University of London, sought to subcontract marking in May 2022.

- Seeking to persuade (including cajole and bully) other staff to break the strike. (This includes union members and also non-union members who bosses might ask to take on additional marking and assessment tasks. This also includes leaning on academic managers such as Heads of Departments)

- VC-oriented managers marking work themselves.

- Rushing marking timings and speeding up submission.

- Using algorithms to approximate missing marks.

- Dispensing with normal ‘quality’ processes, such as second-marking and moderation of marking, use of external examiners and quorum requirements for examination boards.

We need to respond in two ways here. First, part of our more general messaging around the MAB must make clear that staff should not pick up additional marking and assessment work, even if they themselves are not observing the MAB – though, of course, we encourage them to do so. Second, our messaging – amongst our members and other staff, to students and their union, and to the media, the public and politicians – must be forthright, stressing that students have a right for their work to be treated with seriousness and respect; this, in turn, requires robust marking and assessment procedures, including that all work is first-marked and second-marked or moderated by expert scholars. Thus, that if VCs resort to any of the tricks above, then this can only demonstrate their disdain for equity and fairness, for the value of degree and, by extension, for fee-paying students.

Finally, managers will do all they can to deny the MAB’s impact, insisting that while perhaps ‘a few marks’ are missing, everything is ‘normal’. In a nutshell, we must expect bosses to lie, certainly to staff, to students and the media, and, if they believe they can get away with it, to their own governing bodies (university councils) and to the Office for Students. To counter this, we must meticulously gather, assemble and disseminate our own information on the extent and impact of the MAB. This requires commitment and resources at departmental, branch and national levels of UCU.

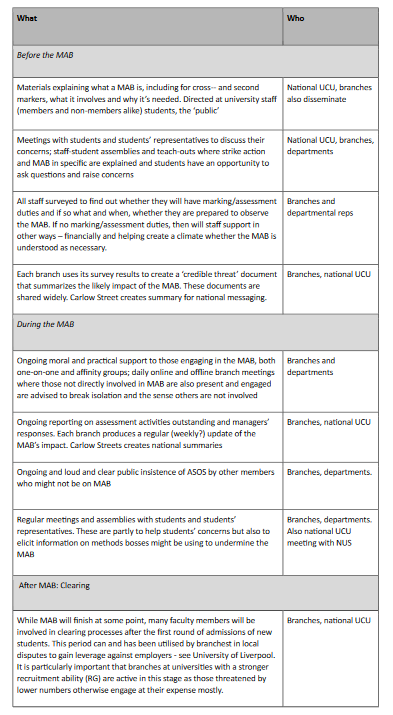

Organizing a marking and assessment boycott – summary

Resources

-

UCU MAB FAQ here (2022).

-

University of Leicester UCU’s guidance for staff here (2021)

-

Goldsmiths UCU produced some useful guidance, e.g. this for students (2022)

-

UCU Left write up on Liverpool MAB here (2021) and a video discussion with a Liverpool organiser here

-

Katy Fox-Hodess resources on scenarios here, 1-on-1 MAB conversations here, organising trainings here, and a downloadable mapping template here

Authors

Katy Fox-Hodess is a Lecturer in Employment Relations at the University of Sheffield and Research Development Director of the Centre for Decent Work. She researches worker power and trade union strategy in a global economy.

Until 2021 David Harvie worked at University of Leicester, where he was Leicester UCU’s communications officer, a negotiator and, for eleven days, vice-chair. He is now a casualised teacher at University of Leeds. He’s a member of UCU Commons and in June will become UCU’s Honorary Treasurer.

Mariya Ivancheva is a sociologist and anthropologist of higher education (HE) and labour: now at the University of Strathclyde, previously at the Universities of Leeds and Liverpool. She works on the casualisation and digitalisation of academic labour and HE alternatives. She is UCU Commons member.

Mark Pendleton works at the University of Sheffield, where he was formerly UCU branch secretary and equalities officer and is currently a departmental rep. He also sits on UCU’s LGBT+ members standing committee and is a member of UCU Commons.

-

Of course, we would encourage university staff who are not union members to join and to participate. ↩

author

The University Worker

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

UCU Marking and Assessment Boycott

by

The University Worker

/

March 30, 2023