Reflecting upon the Hong Kong delivery strikes

by

The Riders' Rights Concern Group,

Chan Ka Wai

September 9, 2022

Two articles on the Foodpanda strikes

inquiry

Reflecting upon the Hong Kong delivery strikes

by

The Riders' Rights Concern Group,

Chan Ka Wai

/

Sept. 9, 2022

Two articles on the Foodpanda strikes

Originally published by Change, the bi-monthly e-magazine of Labour Action China (LAC), covering issues that affect Chinese workers’ rights, especially workers’ occupational health and safety.

LAC is a labour rights non-governmental organisation based in Hong Kong. We are engaged in doing research on working conditions and labour relations of Chinese workers and supporting grassroots organising as well as campaigns for the protection of labour rights in China.

Click here to read their past issues.

Original Editor’s Note:

In November 2021, food delivery couriers of foodpanda Hong Kong launched a strike to protest against pay cut and other issues in working conditions, which forced the company to negotiate with the workers and promise to provide solutions to the 15 demands. The two articles in this issue reflect upon this somewhat unexpected collective action, and imagine the possibilities of building a international gig workers’ movement.

The first article, after briefly discussing the strike’s relevance to the situation under National Security Law, highlights two issues regarding the global movement. First, since many delivery workers are racial/ethnic minorities, inclusion and solidarity across such distinctions is crucial. Second, given the difference between the power relations in the platform economy and that in the global supply chain, there might be potentials for global campaigns to take new forms.

The second article, starting from foodpanda’s map problem (one of the strike’s demand), argues that this gives us insights into two fundamental issues in the platform economy: black box algorithms, and the unequal global division of labour and power. It also suggests that workers and activists need to pay more attention to workers’ struggles in other places in order to build a transnational movement to confront shared problems and the unequal power structures.

After the Foodpanda strike

Chan Ka Wai, February 10, 2022.

It has been about three months after the Hong Kong foodpanda strike in November 2021. Food delivery is one of the fast-growing industries in the globe. The industry prevails in big cities throughout the world. Similar strikes not only occur in Hong Kong, but also in other places, like London and Brussels. More strikes are expected to come due to the increasing labour conflicts in the industry. What can we learn from the recent strike in Hong Kong?

1. Strike under the shadow of the National Security Law in Hong Kong

The foodpanda strike attracted wide media attention in Hong Kong. From the field observation, 30-40 reporters and journalists were waiting for the negotiation result between the foodpanda management and the workers. More than a hundred police were patrolling around. The strike is the first strike after the disbandment of the Confederation of the Trade Unions of Hong Kong (HKCTU) under the shadow of the National Security Law. The strike is not a large-scale one and the workers did not go for petition on street, but abundant media attention had not been expected.

HKCTU’s disbandment has hit the Hong Kong labour movement seriously, but labour disputes will not stop. As a fast-growing industry, food delivery has absorbed many ethnic minorities and young people because the industry does not require high qualifications and is easy to go in and go out. But the labour relation is blurred and undefined. Like many places, food delivery platform companies claim that all workers are self-employed and enjoy high flexibility on their job. The workers manage their own jobs. But, in fact, many aspects of the job are controlled and instructed by the platforms with sophisticated algorithm. Due to keen competition in the industry, food delivery companies have continuously cut the pay. It causes the recent strike eventually.

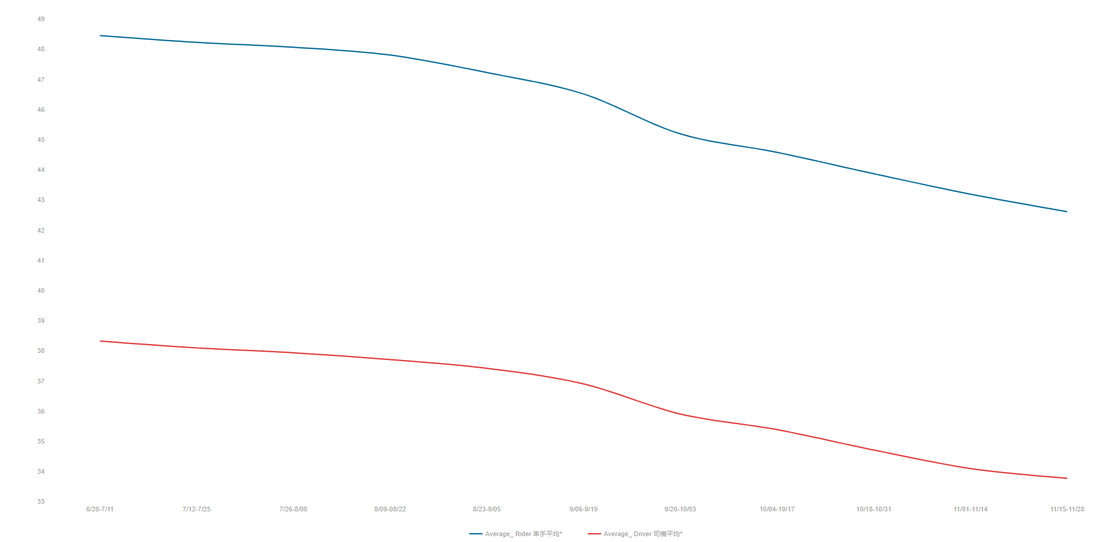

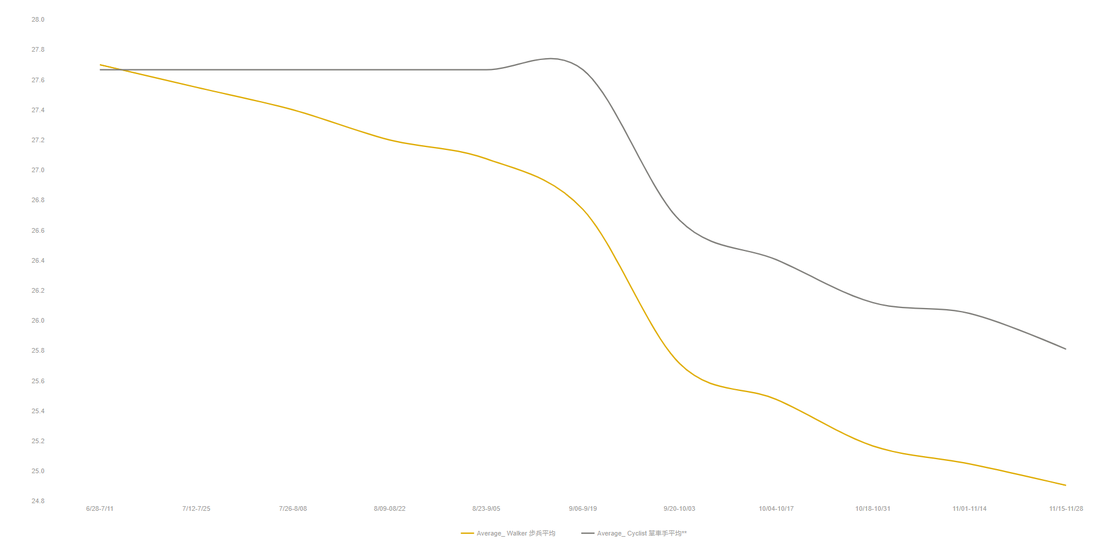

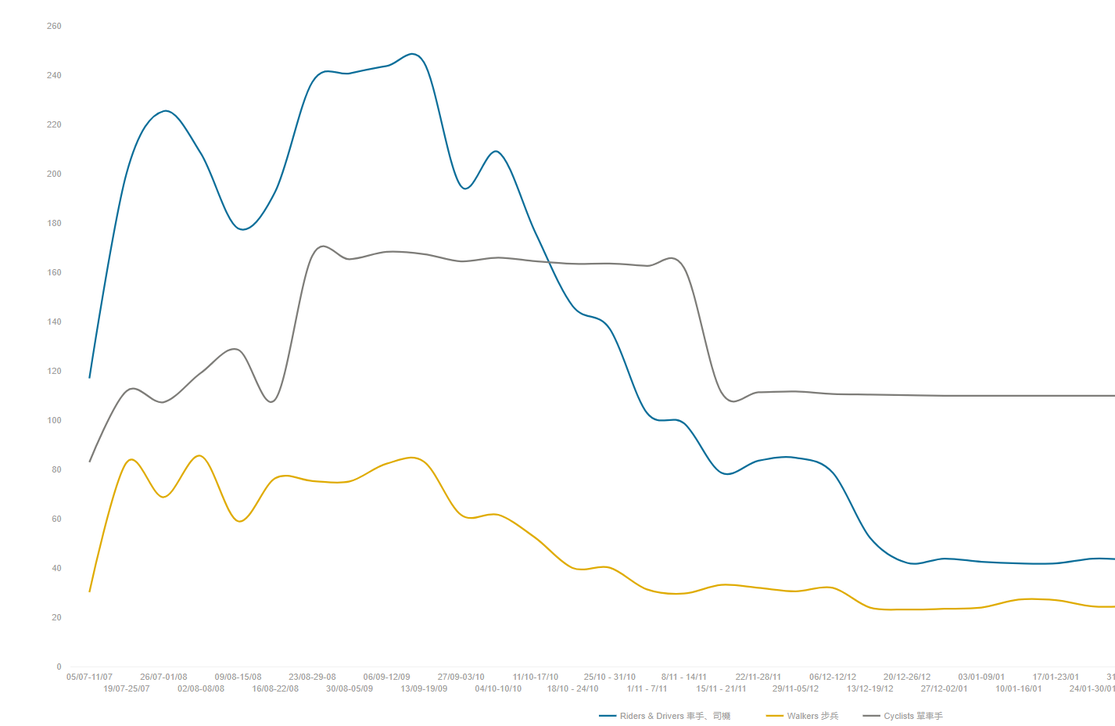

The following charts1 show clearly that the average base pay of all kinds of foodpanda couriers have dropped continuously. The extra service fee at peak hour also dropped until the drop stops after the strike, but the pay still stays in a low level.

Table 1: The trend of average base service fee (Hong Kong foodpanda’s Rider and Driver)

Table 2: The trend of average base service fee (Hong Kong foodpanda’s Walker and Cyclist)

Table 3: The trend of average total peak hour extra service fee (Hong Kong foodpanda couriers)

The strike is over, but the labour relation remains unchanged because the workers’ income does not improve a lot. Therefore, labour conflicts are expected to come. Hong Kong’s trade unions are severely attacked under the National Security Law. Independent labour organizations have become quiet, but the labour relations remain tensed. Now trade union is forcefully marginalized, but the Government is incapable of handling the labour disputes. The existing socio-political situation in Hong Kong makes food delivery workers more vulnerable.

2. Global business

In Hong Kong, the two giant food delivery platforms, foodpanda and Deliveroo, have occupied almost 95% of the total food delivery business. Both platforms are transnational companies. When the workers were negotiating with the management, two companies also mentioned that the local offices could not make final decisions. They had to consult their head offices respectively. The labour disputes in the food delivery industry are not only a matter of local labour disputes, but also a matter of global business. It is closely related to the unequal power structure of global business.

Labour Action China (LAC) and its close partner, Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee (CIC) are relatively experienced in the campaign against global supply chain. Food delivery is in substance different from the global supply chain campaign, but by nature it is still an unequal power structure imposed by transnational corporations. For the Hong Kong management of the two platform companies, the head offices still make the final control. Some scholars suggest that it is still a global supply chain issue with advanced telecommunication.

3. International campaign?

3.1. Racial inclusion or conflict?

In Hong Kong, both the recent foodpanda strike and the Deliveroo strike nearly two years ago were led by the ethnic minorities. Ethnical minorities have been in a more unfavorable employment situation in Hong Kong. Many of them can only find labour-intensive work. In comparison with local Chinese workers, ethnic minority workers have generally worked much longer in the food delivery industry. They see the job as a long-term job for their family earnings, but local Chinese workers comparatively take this job as a part-time or temporary job, especially for those who join in during the COVID-pandemic. In the strike, when all workers suffered from pay cut for each order, local Chinese workers are also terribly angry but they seldom come out to fight for justice. Since the ethnic minorities see the job as a long-term job, any pay cut adversely influences them and their families. They are thus more willing to come out to defend their rights.

The two above-mentioned strikes are dominated by ethnic minorities. It seems that few local Chinese workers joined in. But during the foodpanda strike, many local Chinese workers also joined in the “no pick-up” movement. That was why the foodpanda management were forced to come for the negotiation table in a short time after the strike had begun. In the industry, both ethnic minority and local Chinese workers have their own concern, but this does not mean that both camps could not come together.

It is a world-wide phenomenon that the food delivery industry has absorbed many ethnic minorities in various places. It is not only a matter of labour rights, but also a matter of racial inclusion. It is both to protect workers’ rights and to promote peaceful coexistence of different races/ethnicities in the cities.

3.2 New wine into old wineskins?

In the operation of the global supply chain, there is a clear power relationship shifted from the brand to the manufacturers, and then to workers. The brands can take final control through such shift of the unequal power relationship. On this perspective, the global trade in the food delivery industry is similar because the transnational platform companies hold the power of final control on the delivery system and the working relationship at the local level through an unhuman algorithmic system. The shift of the unequal power relationship is also from the multinational platforms to their local offices and then to food delivery couriers. Telecommunication advance just makes the shift of the unequal power relationship from physical to virtual. Due to its virtual character, the platforms’ economic activities become more mechanical and unfavourable to humans (the workers). But such mechanical system is still controlled by the transnational platform companies. So, such unhuman character is both manipulated and automated.

In the global supply chain, the campaign also goes along similar path as the business. Since production is no longer in the North, the global campaign is decided or dominated by the groups in the North who launch campaigns against the brands with the assistance of the groups in the South. Now can this model in the campaign against the global supply chain work in the global platform economy too? The difference, to LAC, is not the change in the business from physical to virtue. The shift of the unequal power relationship in the global platform economy remains similar to that in the global supply chain. The most different one is that the labour exploitation is not only happening in the South, but also in the North. Labour struggles against the global platform economy have emerged in many cities both in the North and South. The campaign against the global supply chain is a lineal model, from the North to the South, but now the campaign against the global platform economy could be a circular model. Various kinds of local attempts are pointing to the platform economy in their own contexts. We have had different kinds of local attempts against the global platform economy, but a global campaign has not yet emerged. Initiatives across countries in Europe have been raised but their impacts are not yet clear. Some attempts are being made by the EU and international bodies, international unions or labour organizations with the support and assistance of the academics. We hope they could create a new model.

Moreover, there have been similar attempts in the protection of the labour rights of the workers in the platform economy in different local contexts. Most attention was drawn to improve the existing provisions to provide better and wider legal protection in individual counties, but seldom to promote a global campaign or a set of global regulations to regulate the labour practices of the platform economy in the whole world. Provisional change at the local level seems to be the dominant way to protect the labour rights in the global platform economy today.

4. Conclusion

The foodpanda strike is not an isolated case. It is rather a part of the global campaign against the global platform economy. In terms of the shift of the unequal power relationship, the global platform economy follows the same path of the global supply chain. The power is controlled by the transnational platform companies. But the global campaign is not like the campaigns in the global supply chain because the labour exploitation is really global. It is happening in all the main cities in the world. Focus in different countries are dominantly upon the improvement of the existing provisions to regulate the labour exploitations at the local level. A global campaign and a set of global regulations have not yet emerged so far. Moreover, the industry, especially food delivery and ride-hailing services, has absorbed a lot of ethnic minorities in different cities. It is not only a matter of labour rights, but also a matter of racial inclusion and equality.

It is a huge challenge for the international community. Attempts by the international community have been raised but there are still many things to do.

Why Europeans should care about the struggle of foodpanda couriers in Hong Kong

Riders’ Rights Concern Group, March 16, 2022.

Hong Kong FoodPanda couriers are urging the company, owned by Berlin-based Delivery Hero, to update the distance calculation (map) system, as it promised in the negotiation following last year’s strike.

While this dispute appears to be an issue only concerning gig workers in Hong Kong, it offers European readers insights into some key issues in global platform capitalism and highlights the need for global solidarity transcending unequal socio-economic structures.

The map issue

In November 2021, Hong Kong’s FoodPanda delivery workers launched a two-day strike to demand higher pay and better working conditions. One of the key demands was that the app should use a new map (distance calculation) system to calculate the real road distance for pay, because the existing map only calculates the ‘Manhattan distance’ which is often shorter than road distances and thus leads to underpayment. After the negotiation, FoodPanda promised to roll out a new map before February 2022.

However, shortly before this deadline, FoodPanda Hong Kong announced that they would not deliver the new map on time, breaking its promise. The workers’ negotiation team asked FoodPanda twice for an online meeting, which was refused by the company. Later, FoodPanda stated that the new launching time of the map will be September 2022, and the company will pay higher compensations for distance discrepancies before then. It also said that the delay in updating the map is due to the Berlin-based product team of Delivery Hero. But the new compensation remains inadequate, and perhaps no method can fully compensate for couriers’ missing pay unless the company fully updates the map.

Black box algorithms

Although demanding a new map is not a typical demand in delivery workers’ actions, it reflects a fundamental issue workers face globally: ‘black box algorithms’ determining their wage or managing their performance.

While the map calculates delivery distance, the pay rate per kilometre is as important, which FoodPanda always refuses to disclose. Consequently, workers are confused about their ever-changing pay level and have no way to confirm if the company sometimes ‘steals’ some distance pay. Also, even if FoodPanda updates the map system accordingly, it could still make workers’ overall wage level remain the same by stealthily changing the distance pay rate.

Therefore, to truly secure fair pay, workers must further struggle against secretive algorithms, which are used by nearly all gig platforms to exploit and control their workers. For instance, Uber recently started to use an opaque calculation in the U.S. to decide drivers’ pay instead of using ride time and mileage. This is a common battle that platform workers around the world have to fight, no matter in the so-called global North or South.

Global division of labour and power imbalance

In addition to common ‘tricks’ platforms are using around the world, the map issue also highlights the unequal division of labour and power relations between the companies’ headquarters, often within the global North, and the labour, which is often in the global South

Hong Kong FoodPanda couriers are working for Delivery Hero, a German company which no longer has local delivery operations there. Even though FoodPanda has offices in Hong Kong and Singapore (its regional HQ), they have little problem-solving capacity or decision-making power. During last year’s negotiation, Hong Kong’s Operation Team had to consult the German HQ repeatedly for its consent to important changes. Regarding the map, the Hong Kong office also has to completely depend on product development by the German HQ. But the latter broke its promise without any accountability to Hong Kong workers while wielding immense power over and extracting value out of them.

Since the Manhattan system for distance calculation is FoodPanda’s ‘global policy’, it could be interpreted as a ‘technological’ problem relating to local contexts. The Manhattan distance might work for Germany, but it is unfit for places with complicated geographies like Hong Kong and Taiwan. However, why should Hong Kong and Taiwan couriers have to be cheated by an algorithm which makes little sense in the local environment? The seemingly technical map problem is thus a political problem about exploitation and oppression premised upon an unequal global value chain, similar to what is found in more traditional industries.

Conclusion: Struggle beyond borders

To sum up, while Hong Kong workers are controlled by ‘black box algorithms’ just as platform workers around the world are, they are simultaneously more severely exploited partly due to the unequal power relationship in the global platform economy.

But the strike in 2021 showed that Hong Kong workers’ power and agency could make a difference. Thanks to their constant pressure on the company, Delivery Hero is testing a more accurate distance calculation method, which might benefit all couriers under Delivery Hero around the world.

Therefore, due to the transnational exploitation mechanism and the interconnectedness of workers’ future, workers and activists in different countries and regions need to unite, to not only confront shared problems, but also resist and transform the unequal relations reinforced by platform capitalism.

This article has been previously published in ‘Gig Economy Project’ of Brave New Europe.

The Riders’ Rights Concern Group is a labour rights group under Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee. It is dedicated to Hong Kong food delivery workers’ rights and their work includes casework, advocacy, and action.

-

Riders’ Rights Concern Group, Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee, “foodpanda Service Fees Tracker” (Jan 18, 2022). https://www.notion.so/foodpanda-Service-Fees-Tracker-fe887c13b13b4c079e577a745cd46f61, accessed on Feb 9, 2022. ↩

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Rise of Gig Worker Protests in Indonesia

by

Arif Novianto

/

June 8, 2022