Precarity Beyond the Gig

inquiry

Precarity Beyond the Gig

by

Tamara Kneese

/

June 8, 2019

in

Logout!

(#8)

Organizing in Tech and Higher Ed

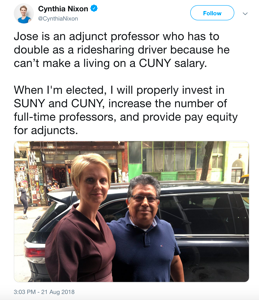

In August 2018, Cynthia Nixon, the former Sex and the City actor and New York State gubernatorial candidate, tweeted about José, an adjunct professor at CUNY who doubles as a ride-hail driver. Nixon’s tweet called attention to the plight of public university workers within the context of New York’s growing wealth inequality and ongoing housing crisis.

Cynthia Nixon with José, an adjunct professor and ride-hail driver in NYC

Despite the fact that tech journalists and media studies scholars often depict gig economy workers as separate from their white-collar counterparts, contract-based positions and precarity are endemic to diverse professions, from higher education to tech. Indeed, as in the case of José, there are times when these two sectors converge. Writing for The Nation in 2016, Alyssa Quart documented how educators in expensive areas like San Jose relied on Uber to supplement their incomes. Uber even sponsored campaigns encouraging teachers to moonlight as drivers. In addition to primary and secondary school teachers, adjuncts, graduate students, and some tenure track faculty members also take part in the gig economy to pay their bills. As in the tech industry, where platforms and corporations profit on the backs of poorly paid contract workers, academia relies on a contingent workforce to function and reproduce itself.

Clear distinctions between the vaunted coder class and gig economy workers may be too severe while also hindering solidarity across tech sectors. Furthermore, many of the problems found within gig platform labor, including part-time or temporary employment status, few workplace protections, and lack of health care and other benefits, are found in other contract positions. Discourses about “doing what you love” or the flexibility afforded by part-time or on-demand work echo those in creative industries and academia. Through my ethnographic research in the San Francisco Bay Area, I have encountered Caviar deliverers who double as freelance network engineers and Lyft drivers who also work part-time in IT. As academics and other cognitive workers have known for decades, prestige and training do not always equal a stable paycheck.1 Even within the ranks of software engineers, many tasks are delegated to contingent or part-time workers, not to salaried employees who enjoy vacation time, health care benefits, and workplace perks. Contractor coders’ experiences can mirror those of adjunct professors in academia, who may have PhDs from top universities and extensive teaching experience, but not be recognized as valuable members of their departments. As a NfB worker inquiry at Goldsmiths found, academics of different class positions often have competing interests (e.g. an adjunct versus a PhD student), thus making unionization efforts all the more complex.

Contract and gig economy workers power the tech industry, just as rampant but under-acknowledged contingent labor allows universities to survive and profit. Historically-driven race, class, and gender-based hierarchies and relationships with gentrification and growing inequality exist in both tech and university contexts. Situating the gig economy within larger frameworks of precarity creates more space for coalition building and organizing across apparent class boundaries. What might organizers in academia and tech, past and present, have to teach each other?

Cognitive Labor’s Shadow Workforce

Scholars and activists have focused on the assortment of jobs related to the tech industry, from Amazon’s warehouses to crowdworkers and Uber drivers, that are not economically and socially rewarded in the way that salaried programming, marketing, and design jobs are. As discussed in previous issues of Notes from Below, contractors in various tech sectors have been organizing, through groups like Tech Workers Coalition, Silicon Valley Rising, and traditional labor unions such as SEIU.

Subcontracted janitors, security guards, van drivers, and food service workers provide essential labor for the GooglePlex, Facebook, and Intel, but are not treated the same as full-time employees. Many of them are immigrants and/or people of color. Gig economy and other contract workers may seem a million miles away from engineers, who perform rarified labor for major tech companies.

There are, however, commonalities between these types of labor. Immigrant software engineers rely on visas and are therefore subject to the same racist and xenophobic policies enacted by the Trump administration. For H-1B visa holders who are contingently employed by a tech company, not immediately finding the next contract gig can mean being forced to leave the country. Even for full-time employees who are visa holders, fears about being fired may impede organizing efforts. The astronomical cost of living in the Bay Area, coupled with student debt, has led some white-collar tech workers to take on side gigs to make ends meet. They may be employed full time, but struggling to pay rent in places like San Jose, Mountain View, Palo Alto, and San Francisco. In San Francisco, the median price of a one bedroom apartment is over $3,200. I recently saw ads for $2,600 studios in Oakland, which is usually considered one of the cheaper living options in the Bay Area. The truth is that even with a prestigious job, it’s increasingly difficult to survive and live well in major cities as the rent and overall cost of living far outpace people’s paychecks.

In response, workers from various sectors, including gig workers and contractors, have come together to form labor coalitions, unionizing or otherwise organizing to make their work more visible. Turkers are also organizing and finding community, despite their isolating working conditions. TWC has held several popular learning clubs on the specific concerns of TVCs, or temps, vendors, and contractors, at major corporations. At the center of these efforts are questions about equity, including affordable housing, fair contracts, health benefits, paid sick days, wages, and disparities related to gender, race, sexuality, immigration, and class.

Such developments are similar to cross-campus organizing at universities, where food service workers, clerical staff, and adjunct professors all fight for formal union recognition or better working conditions. A high percentage of adjunct professors are women of color, just as many contract-based food service and clerical workers at both universities and tech campuses are women of color, and they often receive less pay than their white male counterparts. Similar to the contract-based workers who work in the Googleplex cafeteria or drive the Google van, cafeteria and janitorial staff on college campuses are subcontracted workers, not considered “real” employees of the university as opposed to their full-time, white-collar counterparts. Similar to depictions of tech campuses that obfuscate the diverse kinds of labor that power them, academia is often stereotyped according to Ivory Tower disengagement. Filmic representations of bearded men smoking pipes in tweed jackets are a far cry from the day-to-day operations of a university ecosystem, where contract-based workers toil while administrators at the top reap all the profits attached to a system of student debt and investment capital.

Graduate students are organizing on university campuses, as they have been for decades, and the number of recognized grad unions has grown. Despite threats from a Trump-era NLRB, which has also eroded organizing protections for workers who are classified as independent contractors, private universities have continued to see grad unions win elections. One of the most entrenched symbols of wealth, privilege, and elitism, Harvard University, now has a [graduate student union.] (https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2018/12/29/top-10-2018-grad-union/) Even undergraduates have begun forming unions, recognizing that they, too, provide labor for the university through work-study agreements, marketing, and through the accumulation of debt. In 2017, student dining hall workers at UC Berkeley formed Undergraduate Workers Union, which demanded higher wages and organized a series of walkouts. These actions echoed undergraduate student organizing efforts at dining halls at Grinnell College in Iowa and libraries at the University of Chicago in 2016. Rather than seeing themselves as consumers of education, students were beginning to identity more with the position of worker, linking them to other workers on campus in opposition to university administrators.

As such, looking to organizing campaigns in higher education may pave the way for organizing on tech campuses in major cities. There are structural similarities between universities and tech campuses in terms of the ideologies they use to attract and exploit workers. These points of overlap date back to earlier tech booms. In an article for Social Text, published in 2000, labor theorist Andrew Ross showed how expectations in New York’s Silicon Alley reflected those in higher education, relying on 19th romantic notions of mental labor and self-sacrifice associated with artists.2 In these sectors, professionals might be resistant to traditional organizing. Rather, they view their work as aligned with craft and creativity. Sacrifice is an expected component of both artistic and academic pursuits. Most academic positions are part-time or contingent, but academics are expected to work without discussing the conditions of their labor. The kind of production expected from cognitive workers is about their self-application and unsocial, extended work days. As Ross noted, 1990s Netslaves in Silicon Alley were enticed with stock options, free coffee, the promise of a non-hierarchical office structure, and a Bohemian lifestyle. Many graphic designers and Web developers also worked in contract positions without health care, running on caffeine.

Meanwhile, Ross argues that women and immigrants were expected to take low-paying marginal positions within the creative economy of the 1990s. Thus, it is important to point out that organizing dynamics within Silicon Valley are not new. Women, people of color, and/or immigrants have long performed important but unrecognized work in the tech industry. As sociologist Karen Hossfeld found in her study of Silicon Valley workers in the 1980s and early 1990s, women from the Global South were the majority of contract laborers in tech.3 In a 1993 Wired article, Hossfeld says, “You know, Silicon Valley is famed for its boy-wonder millionaires, but for every one of those people there are a couple dozen others making minimum wage and working in pitiful conditions.”

Such workers were also stereotyped in gendered and racialized ways by their employers, which created spaces for resistance at the same time such discrimination prevented them from officially organizing. Employers will attempt to recuperate immigrants’ social and cultural customs as assets to the flexible workplace and process. Many of the women working in electronics manufacturing that Hossfeld interviewed in the 1980s and 1990s were resistant to traditional labor unions and generally wary of collective organizing. But they did have strategies for dealing with unreasonable, sexist, and racist bosses. Office workers and janitors alike found ways to resist new modes of management and oppression.

From College Dorm to Tech Campus

In addition to these historical reverberations, there are clear similarities between organizing in tech and academia. Consider The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, published by Autonomedia’s Minor Compositions imprint in 2013, which offers a critique of institutions and systems of credit and debt through the radical Black tradition of refusal and fugivity, where the only possible relationship to the university today is a criminal one. Instead of asking for recognition, Stefano Harney and Fred Moten “want to take apart, dismantle, tear down the structure that, right now, limits our ability to find each other, to see beyond it and to access the places that we know lie outside its walls.” For inspiration or cautionary tales, we might turn to other spaces where cognitive workers, like students, postdocs, and adjuncts, work in tandem with clerical staff, cafeteria personnel, and janitors.

In his dissertation and book-in-progress Beneath the University, labor historian Zach Schwartz-Weinstein looks at the complexity of union-based relationships at Yale University in the early 1970s, including “the micropolitics of the university, the affective dimensions of service work and the daily racialized “microaggressions” between managers and managed, between students and workers, and between coworkers … which fell outside the interest, if not the purview, of collective-bargaining-based responses … Centering campus service workers troubles the ways in which ‘the university’ is used as a whitewashed, reductive metonym for intellectual labor.”4 Schwartz-Weinstein’s historical overview of labor conditions on a university campus demonstrates the ways that a unionizing effort, on its own, may not be enough to alleviate structural inequality. In fact, unionized groups with separate class-based interests may find themselves competing with each other. The sharp distinctions between different groups on a tech campus may follow a similar path, especially as the intellectual labor imaginary attached to both tech and academic campuses obscures internal divisions and hierarchies.

The politics of belonging is thorny. As labor organizers in higher education will tell you, convincing doctoral students, especially those in STEM fields, to identify as rank-and-file workers is no easy feat. Those organizing engineers at Google face many of the same problems. Traditional models of staff organizing don’t necessarily pan out in either case. Tech campuses and university campuses, especially in the sciences, are seemingly open and flexible spaces, but they are also extremely hierarchical. Not having the right badge can prohibit entrance to Google, Facebook, or Intel’s inner sanctum, while many academic labs and offices are closed to outsiders. In both university and tech contexts, a focus on cognitive labor and creativity obfuscates the racial, gender, and class dimensions of labor politics on these campuses and their relationship to the cities they inhabit.

Looking to grad student and adjunct organizing campaigns in higher education, as well as campaigns for food service, clerical, and janitorial staff on college campuses, may offer some insights into organizing strategies in tech workplaces. There are several parallels between tech and university campuses. In both cases, only a few positions are recognized as “real” or worthy of attention while many other positions are subcontracted or contingent. Tech campuses and universities have both shaped urban landscapes through development, construction, and hiring practices, contributing to rising housing costs and gentrification. Stanford, the University of Chicago, MIT, Carnegie Mellon, and other major research universities have roles in developing cities according to their visions and often partner with the tech industry. Howard University even has a western campus at Google’s Mountain View headquarters.

The very architecture of tech campuses can resemble the aesthetics of the contemporary university, with gyms, cafeterias, and other amenities intended to attract wealthy elites who can pay full tuition. Thanks to many tech origin stories— from Google to Facebook—relying on the dorm room mythos, the tech industry perpetuates a collegiate lifestyle. Meals are served in cafeterias, encouraging employees to eat on campus rather than going home. The Googleplex and small startups alike are equipped with ping pong tables, bean bag chairs, free coffee, microbrew happy hours, bring-your-dog-to-work-days, and plentiful snacks, all part of creating an atmosphere that blends work with pleasure and leisure. Such comforts may prevent tech workers from thinking of themselves as workers. The Googleplex was also intentionally designed to mimic the university campus in order to “merge the idea of a workplace with experiences found within an educational environment.”

Given these perks and related ideologies, it can be difficult to convince STEM PhD students or software engineers that they are ordinary workers and that it would benefit them to organize or find a way to flex their collective bargaining rights. Traditional models of staff organizing don’t necessarily apply in either case. Having union representatives from the UAW or SEIU visit the campuses might not work for a number of reasons. For one, tech campuses and universities are both enclosed spaces. In some ways, despite their open floor plans, they are meant to keep people out and have various levels of security clearance: I have memories of being physically intimidated by angry PIs at the Sackler Institute in NYU’s Langone medical school while I tried to organize there as a doctoral student and UAW staff member. The different colored badges on tech campuses and limitations on access also make it difficult to have outsiders, like union staff members, attempt to organize in such spaces.

An interesting link between academic and tech labor organizing exists in Stanford University’s not formally recognized union for graduate students. At their first meeting in 2016, there were 3 or 4 CS students out of 30 total attendees. The organizers hoped they could attract more STEM students, especially in Computer Science. To entice Stanford CS students to join a union would reflect the changing nature of the tech industry as well as academia, as it would force CS students to think of themselves as workers, both as engineers and as PhD candidates at a top university. Today, the momentum has stalled, but the STEM folks are in many the most active members of the union; meetings are even sometimes held in the CS department. The grad union focused on student issues, including care for unhoused students. But, as an interview subject also noted, it was difficult to convince graduate students to join in solidarity with striking cafeteria workers. The PhD students weren’t afraid of getting in trouble with their professors or supervisors: they just didn’t see their concerns as related to those of other kinds of workers. Their anti-union sentiment had to with ideology and aspiration rather than fear of retribution. There was not a great deal of pushback from faculty at Stanford. PhD students in STEM, especially in CS, felt they would earn high incomes after graduation, if not before. They were not concerned about their short-term working conditions because they believed that meritocracy would save them in the end.

Today, there are direct connections between some Stanford grad union organizers and TWC, as several TWC members are involved in Stanford’s grad unionizing efforts. This shows that the workplace culture associated with sprawling tech campuses may be in flux. Outsourcing and a shift to contract-based engineering jobs means that those privileged, high-paying coder positions might eventually go the way of academia. There is nothing to guarantee the lucrative positions of software engineers if circumstances change. Joining forces with other workers and even users across tech may offer a way forward.

Both higher ed and tech share ideologies around individualism and meritocracy while remaking cities and workplaces. Workers are not merely content with exploitation because they love what they do, but also because they believe their work is more valuable and they are better than those in less prestigious positions. However, some workers are recognizing precarity as a structural rather than an individual problem. What kind of labor, and what kind of worker, is valued by the institution at hand? Only some kinds of work are visible or privileged, and most are ignored. Collective organizing efforts strive to make formerly hidden kinds of work and workers more visible, and to form alliances across isolated segments of both tech and higher ed. From this historical overview of precarity in tech and its inherent connections to precarity in other creative, white-collar sectors like academia, we can see how discourses around the promises and perils of the gig economy may give way to new organizing imaginaries and cross-class solidarity.

-

Cognitive labor is typically associated with Post-Fordist, immaterial forms of production attached to creative industries. ↩

-

Andrew Ross, “The Mental Labor Problem,” In Social Text 63 (Volume 18, Number 2), pp. 1-31. 2000. ↩

-

Karen Hossfeld, “Their Logic Against Them’: Contradictions in Sex, Race, and Class in Silicon Valley.” In Women Workers and Global Restructuring, edited by Kathryn Ward, pp. 149-178. 1990. ↩

-

Zach Schwartz-Weinstein, Beneath the University: Service Workers and the University-Hospital City, 1964-1980. New York University Dissertation. 2015. ↩

Featured in Logout! (#8)

author

Tamara Kneese

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Organising Silicon Valley's Shadow Workforce

by

Wendy Liu

/

July 31, 2018