McNetworks: Two current modes of struggle

by

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

October 11, 2018

Featured in A Month of Revolt in the Service Sector (#4)

Understanding the convergence of struggles

inquiry

McNetworks: Two current modes of struggle

by

Callum Cant

/

Oct. 11, 2018

in

A Month of Revolt in the Service Sector

(#4)

Understanding the convergence of struggles

The last month has seen strikes at Uber/UberEats, Deliveroo, Wetherspoons, McDonalds and TGI Fridays. Each of these strikes has had a very different political composition, but together they seem united as a coherent movement against low wages in precarious sectors. In terms of the unions involved, they ranged from huge Labour party and TUC affiliates Unite, to small Labour party and TUC affiliates the Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU), to the syndicalist IWW and grassroots IWGB. This article argues that the month of revolt has been the result of two different modes of struggle converging.

The McStrike Model

BFAWU-organised McDonalds workers in the UK had been on strike twice before October 4th. Their much -publicised fast food campaign has already forced concessions from McDonalds. But this was due to be a bigger McStrike than ever before. Not only would a fourth McDonalds site come out for the first time, but two Brighton branches of Wetherspoons would also be joining the fight for £10 an hour and union recognition. As soon as the ballot was announced, spoons workers too won some significant concessions from the employer, multimillionare ‘shitlord’ Tim Martin. TGI Friday workers organised with Unite announced they would also be striking on October 4th - which for some sites would be their seventh day of action. A few days before the strike the government announced new legislation which would deal with the problem of unfair tip distribution which lay behind the TGIs campaign.

The model of these campaigns draws heavily on the experience of the U.S. Fight for $15 campaign, led by the SEIU. In this model, unions aim their attention at the fast food industry and set up well-resourced, highly centralised teams of full timers. These teams then go out and organise for strikes in as many companies at as many sites as possible, coordinating these efforts and combining them with a massive media offensive. They often strike without workplace majorities and rely on social movement tactics and a very strong press campaign to cause reputational damage. Political alliances are also key to the model. In the UK in particular, there seems to be an underlying attempt to prepare the ground for a future Labour government to raise the minimum wage to £10 an hour.

Beverly Silver has made the distinction between associational leverage and workplace leverage. In short, ‘associational leverage’ has its source beyond the labour process, ‘workplace leverage’ has its source in the labour process. The fight for $15 model is based on the maximisation of associational leverage, without paying much attention to the development of workplace leverage. This maximised associational leverage is then directed towards a specific, all-consuming campaign goal (£10/$15 an hour and union recognition) which is often acheived by legislative means.

On October the 4th, the trade unions pursuing this mode of struggle focused their energies on a 11am central London demonstration. Strikers from Brixton (London), Milton Keynes, Watford, Brighton and Cambridge were all brought to a rally of around 300 people in Leicester square. John McDonnell attended and gave a speech in support of the strikes:

The message to every exploitative employer in this country is that we’re coming for you. We’re not tolerating low pay, insecurity or lack of respect. We will mobilise as one movement, the Labour and trade union movement, in solidarity. And I guarantee you this: with strength, determination, courage and solidarity, we will win.

Alongside this, specific workplaces had additional actions at points throughout the day. The strongest action taken by the Wetherspoons strikers was an evening mass rally in Brighton city centre - which, at 300 attendees, was about the same size as the London one. The rally was followed by strong pickets that suceeded in producing some workplace leverage. Whilst to the best of my knowledge every other McDonald’s and TGI’s on strike operated at full capacity all day, the two Brighton ‘Spoons experienced disruption as a result of the picketing and closed early.

This Fight for $15 model has an underlying weakness. Partly as a result of the necessary control required to maximise media coverage and political alliances, these strikes have been heavily centralised. The main decision makers, in terms of strategy, are the media team and full-time organisers. The strike action is directed from above.

This means that the rank-and-file of the union take part in strike action like they’re playing a role in someone else’s’ media stunt, rather than leading their own struggle. They are told what chants they will be using, what T-shirts they will be wearing, what the design on those T-shirts will be, what their picketing strategy will be, which political alliances are being made on their behalf, and where they will stand on the pavement to get the best photos.

This disempowerment inevitably results in frustration. Many decisions made by the union officials and media team went uncontested - but others did not. It became clear over the course of the weeks before and after the strike that a substantial section of the rank-and-file believed that their strategy should focus more on workplace leverage and less on press coverage. The experience of the evening picket only confirmed their suspicion that they could exert more power and create more lasting change in their workplace through a different mode of struggle. Their counter-proposal wasn’t clearly worked out or expressed, but it had widespread support. There was a general sense that power could be found in the pub, not in Leicester square. During that 11am demonstration, the masses of supporters assembled there were not used to picket the (all unballoted) Wetherspoons, TGIs or McDonalds that open onto the square, all of which continued to operate undisrupted whilst workers rallied outside. Customers inside didn’t even realise the commotion was anything to do with the restaurant they were eating in. For some workers, it was an oppourtunity missed. One worker told me they ‘wanted to do more damage.’

It’s important to understand that this model isn’t the only one which has ever had success at McDonalds. There was in fact an internationally-coordinated McStrike in 2002, which was the culmination of a two year organising process in the company led by McDonalds Workers Resistance. In the UK, this involved partial or full strike action at five stores - one more than came out on October 4th. This action was complimented by remarkably militant sabotage actions that varied from cementing the toilets to supergluing tills. There are strategic choices to be made about how socialists organise in sectors like fast food; there is not just one model.

The Courier Network Model

In the UK, this summer has seen the first results of the IWW’s ‘Courier Network’ organising model. This model, based on previous experiences in the sector, revolves around instant messenger groups. These network groups are then supported by external union members who take responsibility for admin and collective representation. The network itself occupies a hybrid position - it is neither a full branch of the union nor fully autonomous from it. So far, this model has been highly successful. Notes from Below has been the main platform involved in investigations of the model in theory and practice, as well as with specific reference to October 4th. This article won’t rehash those discussions.

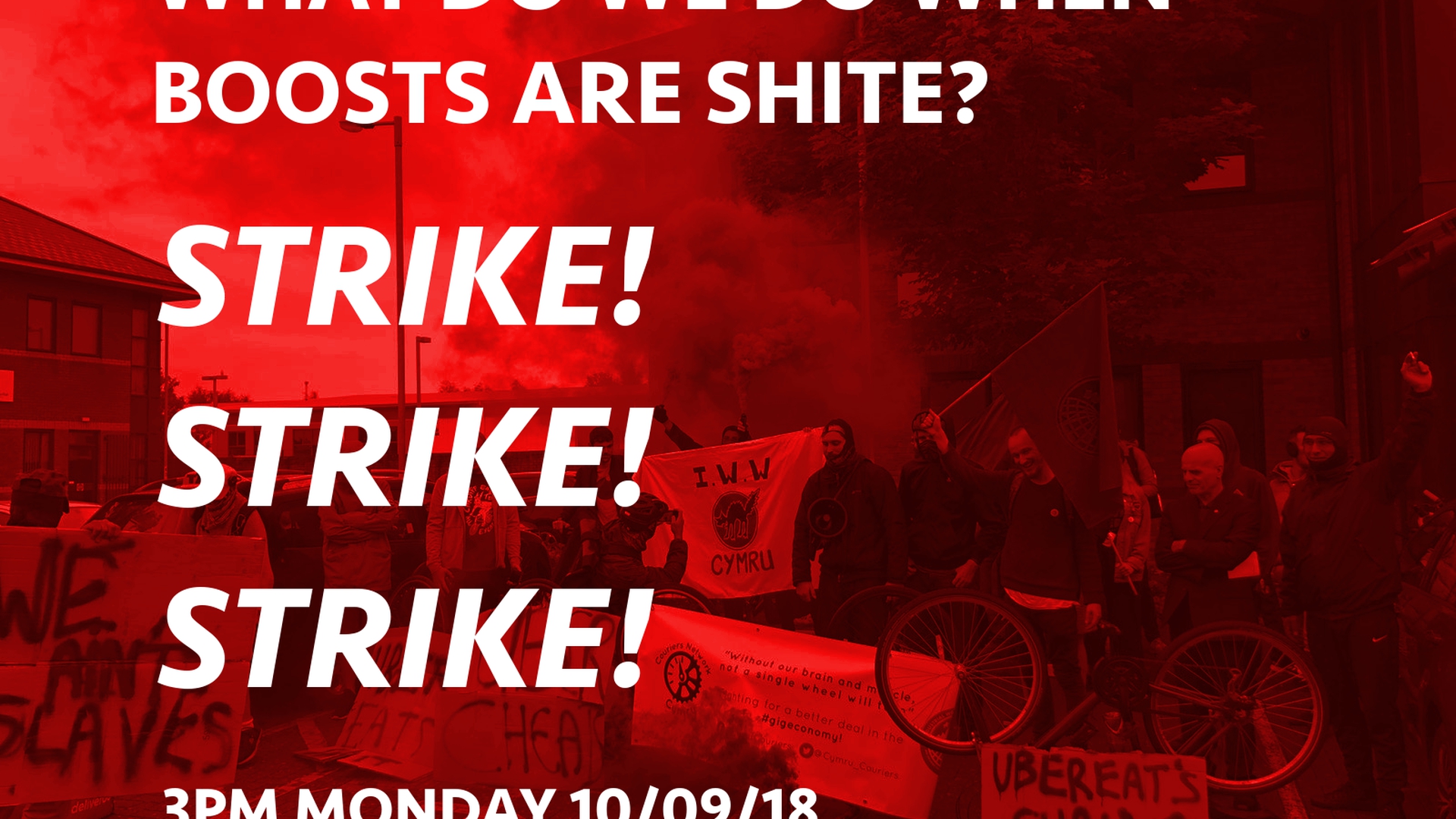

But the network model does provide an interesting point of contrast to the McStrike/Fight for $15 approach. Courier network branches manage to secure workplace majorities and shut down production in their cities. They have developed huge workplace leverage despite being decentralised, highly precarious and spread across a wide area. Direct tactics like wildcat strikes and secondary picketing, long since rendered unlawful/illegal for official employees and trade unions, are their mainstay.

Following local federated local decisions, the eight-month old national network made the decision to set a strike date for October 4th. With just two weeks notice, they were able to mobilise over a thousand workers across the UK. In fact, food platform workers made up the vast majority of strikers during the entire fast food shutdown. In sum, it is a model where workplace leverage is key and the strategic lead comes from below. It has its own weaknesses, particularly with regard to forming political alliances and articulating a clear media line on a national scale. The network has also been unable to force national concessions on wages out of either Deliveroo or UberEats. However, there is significant potential for such concessions to be won going forwards.

What next?

The experience of the past month has exemplified two models for pursuing struggles within the service sector. By no means can we abstract one from its technical and social basis and impose it on another. However, the comparison of the two offers us some insights about what developments socialists and workers need to support going forwards.

Workers at McDonalds and Wetherspoons (and potentially TGIs) will need to develop greater rank-and-file coordination and workplace leverage. Likewise, food platform workers will need to develop a more effective mechanism for forming media and political alliances in order to maximise the impacts of their action. The UPHD organising effort with Uber drivers is a third variant not explored above, which could provide further points of comparison. Momentum’s support for local pickets across the UK was also a novel development, which should be encouraged and extended.

The latest IPCC report has brought many within the socialist movement to the realisation that we have just a few years to begin turning things around. Self-organisation via direct action that builds power in the workplace and community is the only viable methodology to win the coming struggle on warming planet. That methodology needs to be combined with a willingness to argue for what is politically necessary rather than what seems viable within reformist timeframes. The programme of the Labour party needs to be systematically challenged from below: instead of share schemes, we can pose the slogan expropriation under workers’ control. There’s a lot to be getting on with.

Featured in A Month of Revolt in the Service Sector (#4)

author

Callum Cant (@CallumCant1)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Spread the Spoons Strike

Sept. 27, 2018