Lessons for Unison #2

The welcome election of Andrea Egan as General Secretary for Unison hopefully marks a major shift in the political direction and horizon of Britain’s biggest union. As members of UCU, we congratulate our comrades in Unison, and offer a few observations of the past years’ political development in UCU.

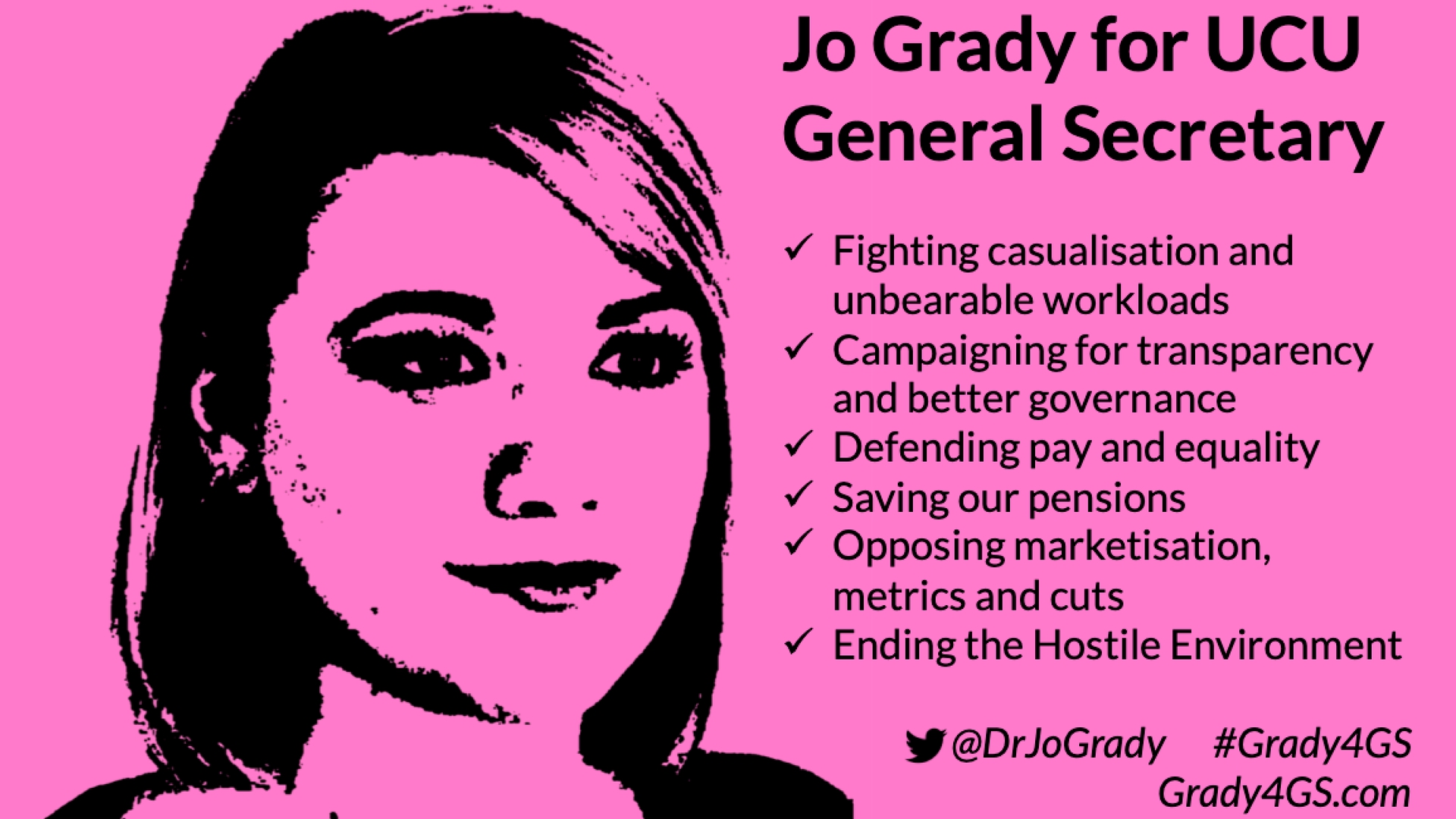

UCU experienced a similar shakeup back in 2019 with the election of Jo Grady to the position of General Secretary. At the time, UCU had only ever had one general secretary, Sally Hunt, who had led the union since its foundation a decade and a half earlier. The political alliance undergirding Sally Hunt’s seemingly unassailable position in the union consisted of both senior union staffers and more conservative factions among the membership.

Sally Hunt’s tenure was marked by a frustrating conservatism, given the dramatic changes that Higher Education was going through. There is no need to rehash all of this here, but, briefly put, UK Higher Education has been subject to a devastating regime of marketisation that has seen the education offered to young people and those returning to education later in life absolutely plummet in quality and massively increase in price. Working conditions for academic, administrative, and blue-collar university staff have been comprehensively hollowed out year on year, with fee money fuelling a temporary speculative spending spree followed by intensifying austerity as the realities hit. Increasingly, academic work has moved from being well-paid, prestigious, and secure towards short-term, part-time contracts, with substantial drops in pay; many academics are increasingly coming to terms with the fact that they are exploited workers, not temporarily embarrassed be-robed professors. In my own university, precarious academics increasingly made common cause with facilities workers through in-housing campaigns, and built links with student activists, a pattern that resonated with developments elsewhere in the sector. In an environment where many university and college workers became increasingly dissatisfied, militant, and creative, the Sally Hunt leadership seemed uninterested in seizing the moment.

These contradictions came to a head with the pensions dispute of 2018; Sally Hunt’s mishandling of that dispute (which saw unprecedented levels of workers’ participation, combativeness, and good vibes all round) led to a march on UCU headquarters by striking workers to directly confront what was widely seen as a sellout by union leadership. It was in this situation that Jo Grady’s campaign for general secretary took off. Her impressive victory as an outsider, at a distance from the entrenched leadership and bitter factionalism alike, completely upset the extant inertia in the union. As Sai Englert wrote at the time of her election :

Her campaign was not only impressive because of the radical nature of her platform, as well as the halt she proposes to business as usual in the union, but also because she stood independently from any of the existing factions inside the union.

At the time, many comrades in UCU felt a great surge of optimism that an independent candidate could and indeed did, comprehensively win an election that, for many, felt like a stitch-up before getting underway. There was a real hope that the election of Jo Grady would mark a watershed moment that would bring the developing militancy at the grassroots level and the union leadership and staff into closer alignment, and perhaps even begin the process of a broad-based campaign for real structural changes to the sector, towards a meaningfully social education system that serves our communities.

This did not happen. While it would be petulant to lay all of our union’s problems at the feet of the general secretary, the “middle management” tier of the union’s staff, or any one of the various organised UCU factions alone, the fact is that the last years have been very frustrating ones for our union. Far from a silver bullet, the election of Jo Grady has coincided with an increase in strife and disorganisation that has hampered the development of effective national campaigns.Despite the radicalism of her platform and her background in independent grassroots action, Jo Grady did not set out on a large program of reform of union structures or staffing. I can not speculate on the reasons for this but the existing union bureaucracy was left largely intact, and as the hopes for a real change in direction on the part of the union leadership faded, relations between the general secretary and large sections of the active membership began to sour. This has been accompanied by an intensification of factional strife, sapping the capacity and morale of many active members and presenting a real barrier for new members to get active.

Perhaps most shamefully, the union leadership has been embroiled in a long-standing dispute with its own frontline staff organised in Unite, in which the former have deployed many of the same harsh, union-busting tactics faced by UCU branches and more senior staff have split to set up their own union branch with GMB.

A series of national disputes have been poorly handled by union leadership, with limited support for branches taking action, confused communications, and serious strategic missteps. In 2023, a national dispute over pay, working conditions, and pensions was abruptly ended without a negotiated return to work agreement, leaving branches flailing and organisers and branch committees embarrassed in the face of their mobilised branches. The major challenges facing our union in the past few years, from the pandemic to the ongoing mass redundancies, have not been faced with anything like a cohesive national strategy, nevermind one that is militant or effective. Instead, individual branches, sometimes branches with a long history of struggle, sometimes branches coming into their own for the first time, have led the fight.

However, this last observation really points to the single most important development in our union over the last few years. The union centrally, be it the national democratic governance bodies, national officers, the regional offices, and senior staff, has, for a variety of (disputed) reasons, not been capable of rising to the occasion. This has left initiative in the union up for grabs, and local branches have stepped up; hesitantly at first but with an increasing assertiveness, branches up and down the country have fought back bravely and effectively against redundancies, often with little meaningful support (or control) by the central union.

The redundancy fights have frequently been local disputes; this has compelled branches to build up local knowledge and capacity. Things like organising ballots, casework support, and local organisational effectiveness, which might previously have been “outsourced” to regional staff, have increasingly been taken up by local activists. The effect has been that despite the battering the sector has had in the past years, it may well be that we have never had a union where know-how, skills, and confidence have been as widely distributed as they are now. The learning curve has been steep and brutal, but thousands of rank and file members have learned how to plan out industrial strategy, organise and win ballots, and sustain gruelling campaigns. There are little green shoots of real rank-and-file organisation that focuses on building power locally rather than getting bogged down in manoeuvres to conquer positions in the national governance structures for their preferred faction.

In a sense, electing an independent candidate like Jo Grady may have been putting the cart before the horse. Sai Englert again:

Indeed, the question will now be how to turn the excitement and mobilisation at the ballot box for Grady into an active, organised, and attentive membership that will be able to support Grady against the old guard, while also keeping her focussed on the union’s grassroots (…) despite the repeated description of Grady as a rank and file candidate on social media by her supporters, this is not an accurate depiction of the situation. Grady is an independent – in the sense that she is not aligned with an existing faction in the union – and a member of USS briefs. She is politically to the left of the union and is standing on a militant manifesto. These are all important aspects of her successful candidature. However, there is no organised rank and file in the UCU and all attempts to form one since last year’s strike have failed to attract more than the usual suspects.

Such a rank-and-file has emerged, but in response to a disastrous series of crises and a breakdown in the union’s capacity to respond. It has not emerged in response to Jo Grady’s election, or indeed taken center stage in the political fights that have broken out since. This is entirely speculative, but it’s very possible that a more organised and actively conservative union leadership would have more actively and effectively stomped out the rank-and-file struggles of the last few years, refusing permission to ballot, cutting backdoor deals with university managements, and demoralising members. Unison branches in Higher Education have often faced obstruction by their union’s governing structures and staffers in a way that most UCU branches have not; it may be that a weakening of the centre through the election, however accidental or haphazard, presents opportunities to ratchet up the fight.

The election of an independent candidate to a position of leadership is not a silver bullet, nor is it a recuperation of struggle: it’s a real victory and a window of opportunity. It’s important to be sober about the possibilities here; huge excitement about a leftward shift in national leadership can rapidly become bitter disappointment when the limitations of the situation become apparent. What’s most important now is that local branches take the initiative and set the tone moving forward, not by fighting for or against this or that leadership but by taking the fight straight to bosses.

author

Solan Gundersen

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Lessons for Unison #1

by

Unite the Union Activists

/

Jan. 24, 2026