Labour Casualisation in UK Higher Education (Part 1)

by

Roberto Mozzachiodi

July 3, 2023

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

Towards a Concrete Politics

inquiry

Labour Casualisation in UK Higher Education (Part 1)

by

Roberto Mozzachiodi

/

July 3, 2023

in

Correspondences from the Upsurge

(Book)

Towards a Concrete Politics

Part 1

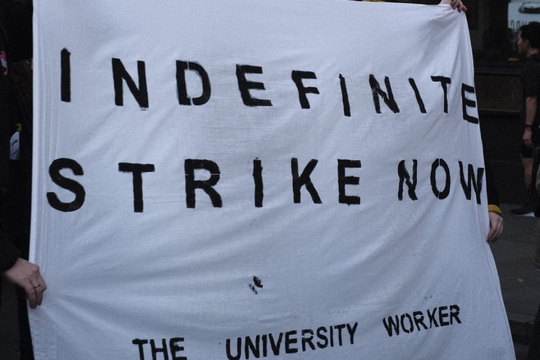

In the last five years the issue of casualisation has risen through the agenda of university unions in the UK, featuring in two periods of major national industrial action (2019-20/2022-23). In this phase, the issue has been sandwiched between other so-called ‘pay-related’ issues within the ‘Four Fights’ dispute claim (that includes pay, workload, pay-gaps and casualisation). This has meant that casualisation has been treated as a discrete issue among others within national collective bargaining.

Over the years, commentators have questioned the strategic rationale of the Four Fights configuration. Originally, the Four Fights was envisioned as a way of addressing poor turnouts in national pay ballots and buoying a strained, if galvanising, pensions dispute. Bringing issues like casualisation and structural racism into the pay claim, while conjoining the Four Fights and the pensions ballot, was viewed as a way to shore up support for action over pay and pensions. In these terms, the strategy has been a success. But the decision to bundle together distinct qualitative demands (with multiple moving parts) and a standard quantitative pay demand has caused lingering problems in national negotiations. It has been easy for employers to baulk at the expansiveness and vagueness of the Four Fights demands and to play issues against one another in negotiations. This has ultimately come at the cost of significant movement on any of these issues at a national level over this five-year period. But for those constituencies whose interests are tied to the Four Fights, there has been legitimate concern that disbanding the demands would spell a definitive end to this dispute. This would mean coming away from a five-year struggle with nothing to show – and would end the relatively short period in the union’s history when demands over casualisation and structural racism had national industrial leverage behind them.

In the Four Fights dispute the demands around casualisation and workload have been loosely defined (though the issues have featured heavily in UCU’s campaign materials) while expectations on pay gaps and rises have been guided by national averages. In the most recent dispute the Four Fights moniker has been quietly abandoned by the national union, with the less ecumenical ‘Pay and Conditions’ taking its place. Clearly, in the context of a wave of high-profile national industrial disputes which have cohered around an inflation-based cost of living crisis, the pay aspect of the Four Fights has taken on conjunctural prominence. However, since the union leadership has done little to concretise the demands on casualisation, this recent prioritisation of pay looks set to overshadow the other issues in the Four Fights dispute.

Despite the crystallisation of these factors in 2023, this turn of events has been long in the making. The politics of anti-casualisation has not developed an organised base within the union membership in any serious way. Casualised workers have not formed a direct expression of their interests as a self-conscious constituency of the workforce. Therefore, the inclusion of casualisation within the Four Fights has always been a top-down affair. Insofar as there has not been a nationally coordinated current of casualised activists operative in the sector, it has always been possible for union negotiators to fudge concessions on casualisation in the last hour.

Anti-casualisation campaigning and organising has undoubtedly had its successes over the years. The disbanding of Teach Higher outsourcing agency at Warwick University in 2015 was the outcome of struggles led by casualised workers working inside and outside of the union structure. Fractionals For Fair Play at SOAS led one of the first wildcat actions among casualised academic workers in 2014 and this was repeated in 2020 by hourly paid workers at Goldsmiths. Across the sector, there have been many successful local agreements brokered on the terms and conditions for casualised staff. While the decasualisation of thousands of workers at the Open University and the Royal College of Art in 2022 was a major watershed for casualised academic workers – marking a crucial step in the movement toward a post-casualisation future for the sector.

However, the level of involvement of casualised workers in these struggles has varied, and the campaigns have remained limited to local workplaces. Indeed, there is little sign that these localised efforts have opened the way to a national anti-casualisation movement – one which would empower casualised workers to determine the strategy and negotiating agenda of the Four Fights campaign. It is little wonder, therefore, that the UCU leadership came away from recent negotiations believing a non-binding consultation exercise on casualisation would satisfy its members.

The current strike wave in US universities (across the University of California system, Rutgers, the New School, University of Michigan, Columbia, Chicago Illinois and many others) has been notable for the mass participation of adjunct and graduate workers. Even more significant has been the politicisation of this layer of workers concerning their structural position and industrial power within the corporate university. This has been in the background of an exceptional growth of workplace militancy in the sector as well as a new repertoire of ‘transformational’ demands which specifically speak to the situation of this part of the workforce. For example, the Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA) demand moves beyond standard wage-bargaining, linking the value of labour flexibility to the cost of reproduction (primarily housing, but also broader living costs such as health). While union bureaucracies have been quick to drop COLA at the earliest sign of an improved deal on existing terms, this demand and its implied analysis has introduced political content to industrial relations in the university sector in the US. This political content consists of workers forming an idenitification as a discrete section of the employment hierarchy occupying a decisive structural position within institutions and the sector more broadly. The effect of this identification has been the cohering of new political compositions within workplaces – where the experiences and sectoral power of non-tenured workers has given shape to organising strategies, political priorities and a collective will to commit to political work and militant action. It has also drawn dividing lines within the workforce, as the power acquired by this composition brings to the surface the disciplinary function of the university labour hierarchy.

This concrete politics, deriving from a concrete analysis of workplace relations, runs contrary to the abstract mass organising/participation models which have become fashionable among trade union bureaucracies. Jane McAlevey’s ‘super majority’ model, which is favoured by the UCU leadership, and which reflects the parameters of US industrial relations, implicitly rejects the role of autonomous political identifications in establishing industrial power in workplaces. The premise of the super majority approach is of a mass adherence to the general principle of power in density. Underlying this premise, however, is the idea that political identifications based on workplace realities are a fundamental barrier to mass participation in industrial actions. It is ultimately for specially selected ‘organic leaders’ to sift out the politically intractable from the amenable, and for negotiators to make the political decisions over how industrial power should be used. Moreover, by basing its conception of industrial power on a critical mass of worker participation, it does not consider how disciplinary power operates through the professional and technical hierarchy of workforces. It ignores the fact that discipline is integral to the organisational and legal structure of workplaces, and that this imposes definite limits over the power that can be mined from the workforce as it is ordered by capital. Therefore, its understanding of the avenues and barriers to appropriating power in real workplaces is not especially enlightening.

That casualised workers have not yet emerged as a collective agent of industrial power in UK Higher Education has to do with the conditions of their work and their position within the labour hierarchy. It also has to do with the organisational structures of the dominant trade unions in the sector and the way these unions carve up university workforces. This is particularly the case with UCU which binds the interests of casualised academic workers to that of all other academic workers based on a shared investment in the non-economic values of intellectual and pedagogical work. Both of these features require analyses based on inquiries into the experiences of casualised academic workers.

The following aims to analyse the process of labour casualisation in UK universities from the perspective of workers - primarily casualised workers. This first part will provide a descriptive analysis of labour casualisation through the lens of employment practices and the existing organisation of university work. The second part will consider the demographics of the casualised workforce and the subjective aspects of casual academic work. The concluding section will draw on these ‘cold’ descriptive accounts to develop a theory of political composition. It will take the process of labour casualisation - in its various determinations - as the key dynamic in university workplaces which has the potential to forge a class composition. In trade union discourse, the term casualisation already implies a political composition. It assumes a common set of experiences and interests on the part of an incredibly composite workforce - one which is segmented by employment, work and status. To concretise this implied political composition, it is necessary to detail the differences and tensions that exist within this workforce and situate these within the context of a living workplace hierarchy. In this way, we can see casualisation not as a homogenous set of experiences and practices but as a dynamic and effective mechanism for regulating the decomposition of all academic work.

The insight of this analysis is addressed to casualised workers in the hope that they can better recognise their situation and their power, and that more inquiries by and for casualised workers can be generated. The collective empowerment of casualised workers will not come from delegating anti-casualisation struggles to the good consciences of senior academics or the expertise of trade union leaders. It will come from developing a shared understanding of how casualisation operates concretely in workplaces, how it introduces labour struggles into the learning processes of students and how it is used by managers to incapacitate forces of resistance. And it will come from testing this understanding within practical struggles.

What is Casualisation?

Employment

The term casualisation has come to be used as a shorthand for a series of changes in the employment structure and the labour process of UK Higher Education over the past 15 years. These changes have roughly paralleled other distinctive features of the economic and policy landscape of the sector. These include government funding cuts, the removal of student fee caps, the increase of student debt (and its recent prolongation), escalating student recruitment targets and the corporatisation of university governance structures.

At one level, the term casualisation refers to the use of a diverse range of temporary and insecure contracts to cover a growing amount of teaching and research work in the university. At this level, the term politically designates a set of employment practices which legally classify workers on the basis of rights, terms and conditions. The range of these contract types and the breadth of their use in the university has increased exponentially as these other structural changes have taken hold.

Contractual arrangements of this sort have been imported from other areas of the economy but have taken up specific functions within the labour process of contemporary universities. Analysing how these employment practices map onto changes in the organisation of university work is an important task for properly politicising the issue of casualisation in HE. The two sections that follow aim to develop such an analysis, beginning first with a survey of the employment practices associated with the process of casualisation in contemporary UK universities.

The main categories of casual employment contract types used across the university sector include fixed term, open-ended and zero hours. Fixed term contracts are the most common type of temporary contract used in the sector and are used to employ workers for a wide range of roles. According to ’21/22 statistics from the HE Statistics Agency (HESA), 33% of all academic staff are employed through fixed term contracts, and these are concentrated among staff below the rank of senior academic.1 The common element in all fixed term contracts is that they last for a definite period of time and there is no guarantee for future employment beyond its end date. In this way, they are typically used by institutional managers to respond to fluctuating labour demands on a termly basis. However, it is becoming more common for employers to use fixed term contracts to cover work that does not vary. As such, these contracts legally empower employers to discard workers for reasons other than demand.

Open-ended contracts are permanent positions by law but in practice many university employers issue what they call open-ended contracts with fixed term dates. 2 These contracts are customarily renewed every year but the employer retains the right to invoke its fixed term basis when the worker is no longer needed. Therefore, this contract type represents a degree of security between a fixed term and a permanent contract.

Zero hours contracts are based on local agreements between an employer and employee which enable employers to bypass the obligation of providing a minimum set of contracted hours. They are typically used as a stopgap to respond to contingent labour demands on a much shorter timeframe than a fixed term contract. They therefore represent the extreme degree of employment insecurity in the sector. 3

In recent years, there has been a growing use of so-called ‘independent contractors’ for teaching activities in universities. Independent contractors are engaged through ‘Terms of Service Agreements’ which are methods of employing the services of workers over an extended period of time without granting the statutory rights of an employee. This enables employers to externalise the costs of basic employment benefits (sick, holiday, parental leave) onto workers, to proscribe trade union representation, and to dismiss workers without notice or justification. The introduction of Terms of Service Agreements tracks onto the growth of enterprise activities in universities such as non-accredited short courses and online services such as distanced learning degrees. The creeping growth of independent contractors in the sector marks the integration of a worker status into the employment structure which is almost entirely stripped of rights.

In addition to these contract types and methods of engaging workers, there is also a growing industry of subsidiary recruitment agencies operating within the university sector. Companies like Falmouth Staffing Ltd (Falmouth University) 4, CU Services Limited (Coventry University) and UAL Short Courses Limited (University of the Arts London) are all intermediary employment agencies operating within university workplaces. As wholly distinct legal entities from their parent company (the university), these subsidiary agencies employ and engage workers as separate onsite employers. This often enables a tiering of rights, terms and conditions between ‘in-house’ and agency workers. In addition, the legal separation of the university as an employer from its subsidiary means that agency workers are annexed from the bargaining unit covered by trade unions recognised by the university. This often means agency workers cannot participate in trade union disputes aimed at improving the conditions of their workplace. It also leads to the separation of management from employer. While agency workers will be de facto supervised by an ‘in-house’ university employee, their legal employer will be the subsidiary agency. This leads to complicated issues around the applicability of internal workplace policies and procedures. These subsidiaries use a range of contract types to employ workers (though Terms of Services Agreements are commonly used) and will employ workers for a range of teaching roles - from high responsibility to taskwork. In a similar vein, many universities establish formal partnerships with external agencies to administer the recruitment of temporary staff (e.g. Unitemps at University College of London and City, University of London and Reed Talent Solutions at Sussex University). In this case, similar issues arise with the separation of employer and manager.

Considering casualisation purely from the perspective of employment practices already provides a complex picture. The degree of temporariness and protectedness of a worker differs vastly across these legal stratifications. These different employment practices therefore constitute material and legal classifications of workers within workplaces. The deferment of employment security carries well documented material consequences into the social existence of casualised workers, while the low (often hourly) pay associated with temporary work makes basic reproduction on a single job impossible. Thus, the gradation of terms and conditions enshrined in the legal parameters of these employment practices sorts workplaces according to contractual protections and benefits.

While these employment practices certainly shape the professional status of different workers and social relations within the workplace hierarchy, they do not completely determine them. More accurately, the professional status or perceived professional status of an academic worker is determined by the way these contract types and legal qualifications map onto the university labour process. This is the second level at which casualisation operates.

Casualisation and the Decomposition of the Labour Process

The work activities associated with casual employment within universities are incredibly heterogeneous. Posts range from those involving comparable professional responsibilities to full time permanent lecturers to those involving the most basic short-term taskwork. The integration of these varied contractual arrangements into the employment structure of the university is linked to the changing nature of the labour process in these workplaces. This is tied to two related phenomena: the financialisation of the university and the swelling of student recruitment targets. In distinct, and often contradictory ways, these factors determine the function of casual employment in universities.

Firstly, the inclusion of a stratified layer of casual workers into the structure of university workplaces enables institutions to remain lean and resilient in the face of market fluctuation and its financial consequences. When recruitment figures are cleared in late summer, university employers can engage or cast-off casual workers as needed, giving weeks sometimes days notice before the start of term. In this way, casualisation becomes a technique for bringing resource management into closer proximity to market demand. The precondition of this technique is a labour market which is able to absorb this financial risk - that is, a market of academic workers who have arranged their lives around a state of perpetual employment insecurity. This opens up the question of the role of the marketised university in producing the labour surplus which is the very precondition of its ability to drive down the cost and conditions of its own workforce.

Secondly, casualisation enables institutions to meet regulatory standards with mass numbers of students. The increasing size of student cohorts (hastened by the recent uncapping of undergraduate student numbers) has fragmented, expanded and rearticulated the work activities involved in the delivery of university degrees. As such, the labour process of university teaching has disintegrated, with multiple differently contracted workers performing discrete tasks that would have previously been integrated in the workflow of a single or a small team of permanent academics. 5 For example, one student could have a permanent academic delivering lectures for the duration of a programme, different fixed-term graduate teachers delivering classroom seminars on modules and independent contractors providing summer dissertation supervision and coursework assessment. This technical recomposition of the labour process corresponds to the demands of replicating a standardised educational experience in a mass university context. 6

While the labour process of the university has been dispersed across a highly differentiated and modular workforce, the quality of degree content and delivery continues to be regulated by student and consumer standards authorities (The Office for Students and the Competition and The Competition and Consumer Protection Commission.) This means the work activities normally associated with casualised contractual terms are marked by a contradictory demand: that is, of maintaining a level of ‘educational quality’, consistent with regulatory and academic standards, via contractually degraded taskwork. The source of this contradiction is not just that casualised workers are paid less or have worse T&Cs than the permanent worker whose quality of labour they must replicate. It is also that the truncated nature of the taskwork makes it practically difficult to realise that quality. Since most of the work associated with casual contracts is divorced from curriculum planning decisions - tasks coming at the content delivery stage alone (class-room based seminars, tutorials, supervisions, marking) - casual workers are rarely fully aware of what the quality of their labour is expected to be or how it should be articulated with other work activities within the broader labour process. In other words, it falls to the casualised worker to compensate for the fragmentation of the labour process in the mass university. They will most likely have disciplinary expertise, pedagogical know-how and experience of being a student in comparable teaching contexts. However, it is unlikely that they will have direct access to their line manager’s rationale for how a given teaching task is supposed to match up with regulatory standards, principles of educational transfer and intellectual properties.

Instead, casual workers encounter this rationale in a mediated form: through course outline documents which are provided to students by course leaders. These documents reformulate regulatory standards in the register of attainment metrics. Expectations of what students should achieve in order to merit a given grade are stipulated as a series of graduated learning outcomes. In this way, learning - a process which is fundamentally unstable because relational and experiential - is converted into fixed measurable benchmarks. At the same time, these metrics also specify the work of the casualised academic. It becomes the job of a casual task worker to devise teaching methods which generalises the attainment of these learning outcomes for growing cohorts of students. Most often, they will have to do this without having taught the material before, without a guarantee of teaching it again and with a highly peripheral relationship with the workplace.

Despite this contradictory demand, there is a certain level of professional ‘freedom’ created by this situation. The isolation of the worker, the indirectness of their management, and the contingent nature of ‘effective’ or ‘productive’ teaching work, means that the casual academic is forced to take a significant degree of personal responsibility over what they do when they work. However, this freedom is conditioned by expectations that are instilled in students by university marketing rhetoric. Most students arrive at university believing that the teaching staff delivering their degrees are of a comparable level of academic experience and professional embeddedness. In this way, pedagogical autonomy, and the non-instrumental nature of teaching work, become means through which casualised labour is disciplined. Where student cohorts are led to understand that teaching staff are part of an integrated academic body, casualised workers are inclined to supplement for the professional and contractual discrepancies which underlie this misrecognition. Practically, this means they will aim to emulate their permanent counterparts in teaching scenarios which will involve a significant amount of unpaid preparation work. Academic task workers are thereby subject to an intensive form of exploitation where they are compelled to produce surplus value far in excess of their permanent counterparts.

In summary: the competing managerial priorities of upholding regulatory standards and maintaining labour flexibility in the mass university form the basis of the experience of the casualised academic task worker. They bear the sharp end of the recomposition of the university labour process as it is more fully subsumed to the market. Aspects of this contradiction become apparent in classroom situations: when, for example, tutors encounter the irreconcilable needs of the mass student body through the confines of a seminar session, and their basic responsibilities as workers become unmanageable.

Using casual contractual arrangements to employ pedagogical task workers is the main function of casualisation in UK HE. However, there are also forms of casualisation specific to research work. The race for income generation in the corporate university sector has resulted in the growth of highly contingent funded research projects and their integration into the economy of the university and the organisation of university work. This has given rise to two further areas of labour casualisation. The first derives from the one-off jobs generated by research projects. The nature of these jobs vary according to the discipline and the research targets, and the length of contracts depends on the parameters of funding. The second stems from permanent staff being ‘bought out’ of their teaching activities to carry out research thereby generating short-term cover posts. The latter represents a countertrend to the widespread use of insecure contracts to hire task workers. Here, posts involve a relatively high level of professional and pedagogical responsibility, covering established positions which are integrated into the broader workflow of degree provision and departmental culture. These roles will entail most, if not all, of the content production work of their permanent counterparts (planning, designing, delivering courses, and other departmental administrative duties) but will be underpinned by similar contractual terms as academic task workers. In this case, the worker will have oversight of the broader processes surrounding degree provision. However, since this will be a temporary cover position, they will be similarly compelled to emulate the professional experience and embeddedness of their permanent counterpart.

These distinct forms of casualised employment attract different degrees of professional status and rank. This will normally depend on the level of responsibility vested in a given academic position. For example, academic task workers have a relatively low level of responsibility and therefore tend to occupy the lowest rank in the professional hierarchy. Cover posts will tend to attract a higher status because they derive from an existing permanent position. Whereas research posts are harder to determine because they are linked to intellectual work which carries a peculiar form of prestige (see part 2). This tiering of casualised posts is also conditioned by the demands of a slack labour market. At present, job adverts for permanent academic posts expect candidates to evidence experience of an increasing repertoire of professional responsibilities. Hence, casual academic work becomes attractive due to its professional development function.

This segmentation of casualised workers across the university labour process has wide ranging disciplinary functions and forms specific subjective conditions. The different routes into casualised academic work and the different demographics that are formed by these trajectories play a critical role in this process. These are important things to consider because they indicate the kinds of motivations people bring to casual academic work and the ideological forces which shape how they negotiate with employment conditions and the recomposition of university work. It is crucial to follow these threads to track the concrete development of a political composition from a state of technical recomposition. The next part of this analysis will consider these aspects in detail.

-

In ‘21/22, 77,475 out of 233, 930 total UK academics were on fixed-term contracts. 96.4% of those on fixed-term contracts were below senior academic level. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/staff/employment-conditions ↩

-

HESA include open-ended contracts within the permanent contracts category in their breakdown of the employment status of academics which gives a skewed picture of permanent employment in the sector. ↩

-

21/22 HESA statistics show that 1.9% of all academic staff were engaged using zero hour contracts. While it is the case that the use of zero hour contracts in the sector is marginal compared to the use of fixed term contracts, it is hard to imagine that these figures are easy to accurately establish given the peripheral status of these workers. ↩

-

Through negotiations with Falmouth UCU, Falmouth University has formally agreed to bring on-campus academic staff employed through Falmouth Staffing Ltd in-house from 1 August 2023. This in-housing will take place on a voluntary basis and does not cover academic staff teaching online courses. ↩

-

A key driver in the development of education technology has been the demand for logistical management of large numbers of students. For example, assessment software Turnitin rationalises plagiarism checks, standardises feedback formats and radically cuts down on overall assessment labour time. Meanwhile the student attendance software SEAtS automates student attendance registration by forcing students to use an app-based clock-in system. This software also automates the bordering of the student body. ↩

-

A paralleling dynamic occurs to permanent academic posts. A series of managerial, administrative and marketing tasks are detached from the remit of dedicated workers, and redistributed into the role profiles of permanent lecturers. While many have highlighted the proletarianisation of academic work, few acknowledge the concurrent managerialisation of senior academic posts. ↩

Featured in Correspondences from the Upsurge (Book)

author

Roberto Mozzachiodi

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

UCU and the University Worker: Experiments with a bulletin

by

The University Worker

/

April 28, 2023