You'll Never Guess Why These Millennials Took Pics of Hair Products For €€€

by

Richard Hames (@richardjhames)

March 30, 2018

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

The underpaid, fragmented world of the clickworker is controlled through obscure algorithms. What new tools does the left need to understand it?

inquiry

You'll Never Guess Why These Millennials Took Pics of Hair Products For €€€

by

Richard Hames

/

March 30, 2018

in

Technology and The Worker

(#2)

The underpaid, fragmented world of the clickworker is controlled through obscure algorithms. What new tools does the left need to understand it?

At 14:42 on Tuesday 27th June 2017, thousands of ‘clickworkers’ around the UK received an email entitled: ‘UK Project: Get 10€ for taking Pictures in Stores till Friday’, containing a task in four steps:

- Go to a Boots or Sainsbury’s and take some pictures of hair products

- Open a page on the clickworker.com website, and upload the pictures

- Open GPS on your phone and allow GEO capturing of your location

- Follow some simple instructions on a webform

The result is that someone goes to a shop, makes straight for the hair products, picks them up in a certain order, takes photos, stands around uploading information to the net, and then leaves having bought nothing, €10 richer. Nothing on the website tells you why anyone should do this, or what purpose it ultimately serves, and it’s not clear why it would generate any kind of value for anyone, let alone €10 for the photographer.

Clickworking, a set of competing platforms for small tasks performed by a widely distributed set of workers, is a growing industry. Companies put small tasks they need doing on an online platform, accessible from an app or online. They are then performed online or locally by workers employed for a single task at a time. The pay is hugely variable, and some platforms like Amazon Mechanical Turk have several levels of workers who are paid differently for the same task. There is no clear consensus on what it is that places workers on different wages levels.

Here’s a theory: the web bots of a web marketing research company, scouring the internet for the strength of connections between various search terms, like ’Sainsbury’s’, ‘Boots’ and ‘Hair products’, had detected that Boots and Sainsbury’s positions in web searches for ‘Hair products’, and a host of similar searches, had fallen below some kind of threshold the companies had specified to their marketing departments. This had triggered a message to those departments, letting them know that their branding was in trouble. The marketing departments had then instructed Clickworker, and perhaps other crowd-sourced micro-task platforms (like Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, which is not so established in the UK as the US and India) to broadcast an advert for a job, which was then carried out by a subset of the 983,314 active clickworkers on the website, of whom 26,746 were online at the time of writing this article. There are no published demographics of the average clickworker, but it seems reasonable to assume they are fairly young and tech savvy, having as yet been unable or unwilling to find more conventional employment. They have a strong cultural influence in the space of the internet, but this influence expresses itself just as much in the subterranean machinations of server farms as it does in the human-readable cultural changes more readily discussed by people. These people then uploaded the pictures they had taken, with all the various extra bits of information that go along with them, like their location and habits and a complete consumer profile for them built up over years. Thus, the firm connection between ‘Sainsbury’s’, ‘Boots’ and ‘Hair Products is reassociated deep in the mind of Google, Facebook, and other online algorithms.

What is it like to be always massively mediated in your work? Mediated through the app, through the algorithm, alienated through the sheer scale of distribution? Of course alienation has always been, and always will be, a component of the experience of being a labourer under capital, but the difference here, and perhaps a unique difference in the history of work, is that the aim of the task, for thousands and thousands of people, and perhaps even for everyone involved at every level, is unclear. Is it not true that all work under capital seems wasted in the service of an inscrutable logic?

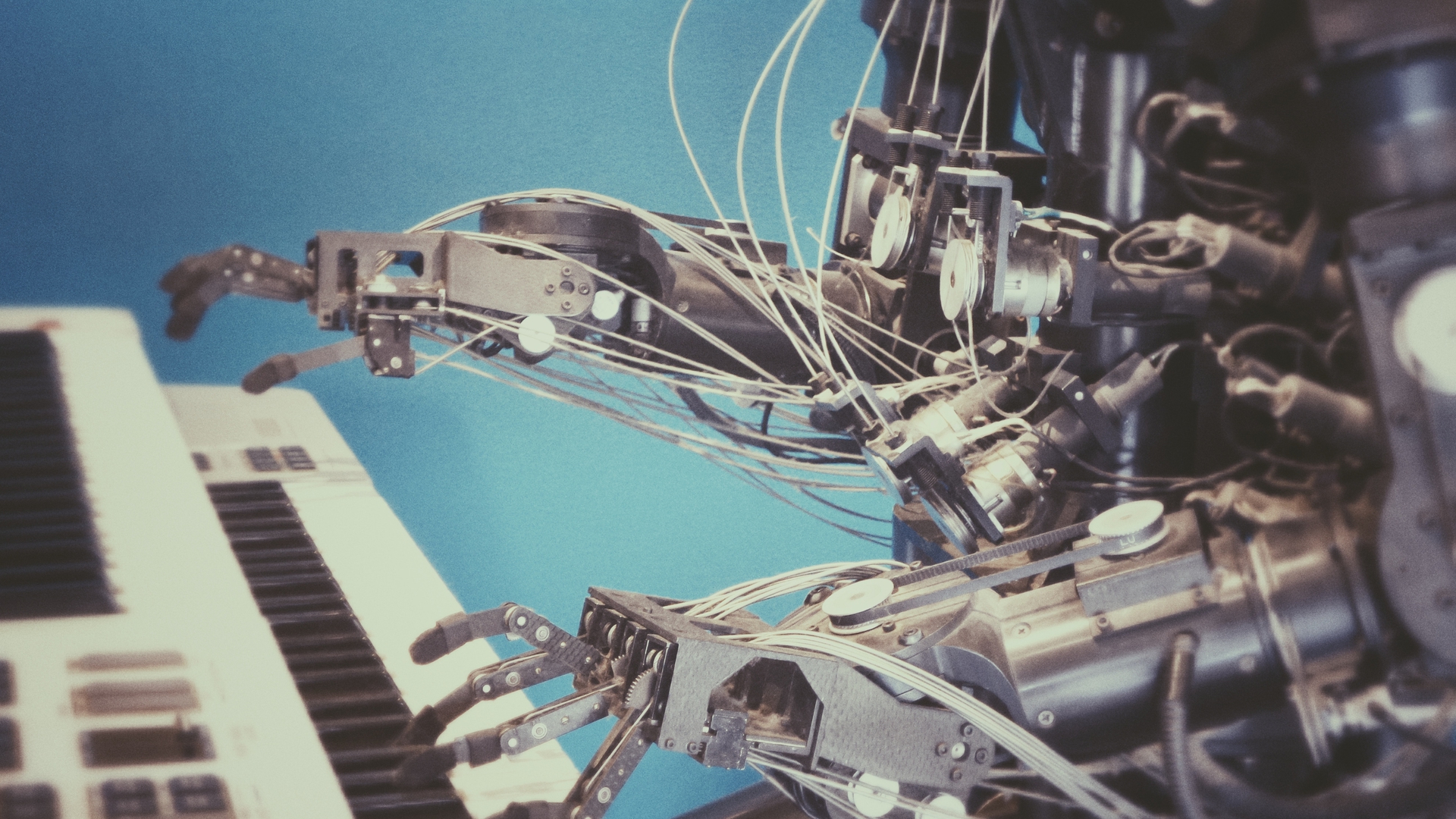

Next time one searches for ‘Hair products’, one may well find that Sainsbury’s or Boots appear higher up than they might have done before. Or, perhaps, not. But either way, the labour will have been absorbed back into the inscrutable functioning of the algorithm itself. This article too, appearing online or in print, and the the metadata buried deep in the image at the top of this article, will be analysed by other bots, and will also contribute to strengthening connections between these two searchable terms. You as reader are participating in this work by reading this article. When will clickworkers receive their first ‘UK Project: Get €10 for writing article about clickworker task for media organisation’ email? This labour, and much contemporary digital labour, is a strange theatre of actions, performed for a spectator, the Google PageRank algorithm and its equivalents, of unimaginable breadth of insight, but who can still be fooled by the cynical work of meatspace humans.

Clickwork has arisen as a particular form of work only in the last decade or so. What future is there in this? The question really hangs on another question. Can algorithms that see our movements learn to distinguish our feints, performed as labour, from our ‘real’ interests? It’s the same question as, ‘at what point in the analysis of faces will smartphone cameras become better at distinguishing fake smiles from real ones, and start adjusting our profiles accordingly?’ Facebook, Instagram, and all other major players have policies against the manipulation of their algorithms, but for the time being they themselves rely on a huge input of human labour to find these fakes.

The most concentrated and efficient form of this manipulation takes the form of ‘click farms’. These have been likened to a sweatshop with computers, mostly based in warehouses in Bangladesh and South East Asia and are staffed by workers who click through thousands of likes on multiple platforms to generate the illusion of engagement. In her essay ‘Proxy Politics: Signal and Noise’, Hito Steyerl has written about the process of ‘astroturfing’: the production of an illusory political support on Twitter through the mass use of bots. Most famously, of course, a similar alleged programme of manipulation took place in the US election 2016. Garrett Bradley’s 2016 documentary ‘Like’, which came under heavy criticism for its instrumentalisation of Bengali workers to automatically produce feelings of sympathy in its smugly concerned liberal audience (those feelings themselves a kind of affect-for-sale) nevertheless also explores this world more thoroughly.

One technical difference between the comparatively well-paid work of the European or American clickworker and the work of those in clickfarms is that they are almost exclusively using their own, well-established social media accounts, and not newly created fake accounts. However, what the characterisation of this work as ‘manipulation’ (as opposed to the more ‘genuine’ activity of liking on social media of one’s own accord) misses is that there is no primary, ‘authentic’ activity of attention and interest under capitalism. Both the activities are structured by an involvement with the wage form. The difference lies in the degree of mediation. The much publicised Wages for Facebook begins from this position.

Online residues of data are far from autonomous from our actions offline. The online world’s order and utility for companies is propped up by a granulated mass of workers, flowing about the world performing strange actions to influence the weightings of online power. In other, more visible and often more urgent ways, the ‘objectivity’ of algorithmic structures has been questioned. Police forces using data from a racist history of arrest, harassment and prosecution, are shocked to learn that the algorithm also profiles criminals as black. It’s not that the algorithms are racist, it’s that the data is. And of course it’s clear that this data is produced by humans, and so it can be manipulated by them too.

The suggestion above for the purpose of this particular task is simply a guess. What is necessary on the left, if this work is to be understood, is a more thoroughgoing knowledge of the workings of algorithms. The most drastic conclusion above - that for the first time in history workers simply can’t understand what they are doing, trying to manipulate a machine - is of course not true. There is nothing fundamentally inscrutable about algorithm-driven work, at least not yet. It is possible to know. But the task for the left is to understand these algorithms better, in order to organise effectively. What is required from the practice of worker’s inquiry in the contemporary age is a thoroughgoing understanding of this domain.

This work of making contemporary algorithm-driven work legible must be undertaken as quickly as possible, and as communally as possible, or we may find that the world, and our part in it, becomes unknowable for us.

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

author

Richard Hames (@richardjhames)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Microresistance: Inside The Day of a Supermarket Picker

by

Adam Barr

/

March 30, 2018