Microresistance: Inside The Day of a Supermarket Picker

by

Adam Barr (@Adambaa13)

March 30, 2018

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

Technology used for control can also present opportunities for resistance

inquiry

Microresistance: Inside The Day of a Supermarket Picker

by

Adam Barr

/

March 30, 2018

in

Technology and The Worker

(#2)

Technology used for control can also present opportunities for resistance

Due to intense competition between the major players and an excess of supply, profit margins in the groceries industry are thin. In the online groceries market they are thinner still, as all the extra operation and labour costs of picking, storing and delivering goods puts additional pressures on companies. The only way to reliably deliver profits in this domain is through a tight regulation and surveillance of work. This regulation and surveillance manifests in the same technology used to carry out the work.

I worked as a picker in a large branch of Sainsbury’s in a north London suburb for several months in 20161. Picking here refers to the job of walking the aisles of the supermarket—selecting items for eight different orders at a time and storing them in assigned boxes in a cart, a single step in the delivery of an online order. The demographics of non-management staff in my store were varied, a wide range of ages with more women employed than men. Around half the staff were employed solely in the department, whilst the other half only took on online shipping shifts as overtime, whilst primarily being employed in other departments. In this article, I want to focus not so much on the experience of the work, but how we can struggle against it.

User Login Error

The work itself is managed through handheld electronic devices. Each picker has a unique login, and productivity is tracked over time and flagged at weekly evaluations. Most pickers start their shift at 5am and continue until 9:30am, with some pickers staying on longer to fulfill deliveries scheduled for later in the day. The shop opens at 8am and after this, one must work around the customers, making sure to give way at all times. Pickers are usually given eight orders to complete in a run and work in sections such as frozen, chilled or ambient.

For workers taking online shifts as overtime, productivity data did not feed into the targets we were given. However, for those who work solely online, productivity contributed to an average performance target for all workers. This target is generally applied with no time given for travelling to a starting location, picking unwieldy or heavy items or performing customer service. In my store, pickers regularly failed to meet their targets, which turned the weekly evaluation into a somewhat ritualistic humiliation. Although failure to meet targets was rarely, if ever, used as the sole reason for a firing, it was still regularly brought up in disciplinary proceedings as a means of disciplining workers.

The effect of constant targets—or rather, a constant failure to meet targets—is disempowering, even demobilising. It creates a sense that your failure isn’t a product of unrealistic targets, or even the rigorous strictures of the work behind the convenience of online grocery, but instead the result of an individual lack of effort.

USDAW <3 Bosses

In such conditions, one can imagine that there are many areas to be improved, so a trade union should be the natural answer. The main union in our branch is USDAW (Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers - pronounced ‘uz-daw’), a ‘partnership’ union, whose primary activity is making partnership agreements with employers in exchange for access, i.e. the opportunity to influence upper management. On their website, USDAW states their purpose as ‘establish[ing] effective industrial relations with employers to achieve the best possible terms and conditions.’ In reality, this amounts to another means to manage workers, acting to relay the inefficiencies of work to managers; not to improve conditions for workers, but to benefit Sainsbury’s as a company.

USDAW is namechecked in training, but membership is not automatic. I didn’t actually meet the rep for three weeks. Indeed, there was no consistent union presence in the workplace at all. The only indication of their existence was on a training DVD shown in the course of the two days of induction, which featured the general secretary of USDAW standing next to Sainsbury’s Head of Human Resources, discussing how well they got along, and how the business and the union helped each other. I took this to be a deliberate tactic to disempower workers—what was the point of being a member of a union so obviously committed to the preservation of good relations with management? This is is further backed up by workers’ activities organised by the company and a veteran’s associations for ex-employees, all of which steer Sainsbury’s away from being a workplace with inherent antagonisms and towards being a social organisation within which workers and management can co-exist.

Victory Underway!

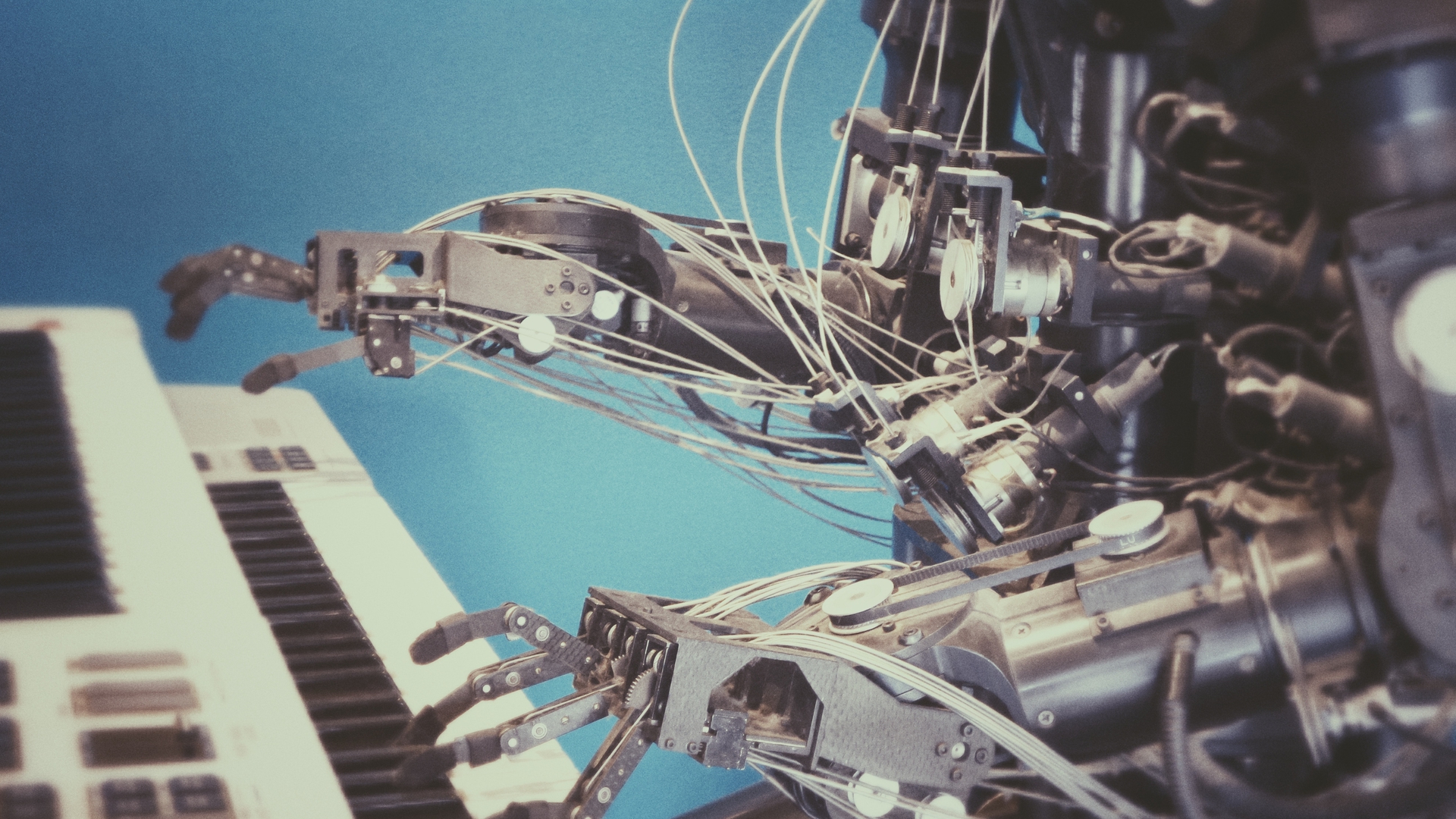

Although the technologies—algorithms, DVDs, handheld devices, etc.—are relatively new in their use in work, the underlying motivation remains the same. Online grocery retail is only profitable within a relentless drive for efficiency, manifested in the continuous development of structures of exploitation of workers to maximise profit. A focus on the specifics of the case of supermarket picking shouldn’t lead to a sense that there is nothing in common between sectors. We can look to actions in other sectors, such as the courier industry, and the organisation of cleaners in universities, media organisations and government departments.

Part of the challenge of working in the presence of an opaque technology is that it obscures traditional tensions in the workplace, most notably the one between managers and workers. Instead of taking responsibility for the targets set, and having to defend those targets to union reps, managers can make the somewhat legitimate defence that algorithmically-set targets are out of their control.

On the other hand, that opacity can also be useful in a worker’s struggle to make their job more bearable. William Golding, who worked as a picker in a large Sainsbury’s store in the south of England, told me he periodically kept his handset logged in for the duration of his lunch break, making his average weekly pick rate plummet and making the algorithm set a lower pick target for the store in the subsequent week. He received a disciplinary for this, but it was more preferable to receive a disciplinary for human error and serve out a probationary period rather than regularly missing the weekly targets. In another instance, a co-worker of mine who’d worked in the store for several years would occasionally leave his device slightly out of its charging station at the end of his shift so that it would run out of charge a few hours into the next shift. This meant he could take an additional five- or ten- minute break while the manager on duty sorted out a replacement handset.

These acts are just two examples of latent resistance with which workers are constantly experimenting to make their jobs easier. The challenge to activists within the supermarket sector is to generalise these practices and to coordinate them in conjunction with more overt forms of action such as strikes.

Speaking of strikes, member-led unions, such as the IWGB (Independent Workers of Great Britain) and UVW (United Voices of the World), have opened up new possibilities for retail workers. Victories in London universities, couriers strikes and ongoing disputes with luxury car dealerships have broken the consensus, prevalent for decades, that grassroots unionism is not a viable strategy for securing better conditions. In contrast to the partnership/collaborative strategies of the major retail unions, adversarial member-led organising has proven that precarious working conditions aren’t an excuse for capitulation; they’re a reason to fight.

In the context of online grocery, one worker making a fuss would be a target of discrimination from management. However, the ongoing emphasis on collective action is an effective counter to victimisation practices, more so in recent years in light of the national scandal of blacklisting in the construction industry. One can see that, in the case of UVW and the Ferrari dealerships , reprisals against union activists acted as catalysts for further strikes and actions.

Further encouragement can be taken from the proliferation of workers’ bulletins: anonymously written newsletters written by and for workers which serve as a means to agitate and organise. Examples of these are the bulletins produced for workers at Amazon’s Hemel Hempstead fulfilment centre by the Angry Workers of the World and the Supermarket Worker produced by Notes From Below. Bulletins like these are an effective means of agitation precisely because they place themselves outside an employer’s mechanisms of control. Workers can talk to each other in a language unimpeded by the considerations of keeping their jobs, away from the staff associations and Great Place to Work groups that set the boundaries on what are achievable victories within the workplace.

Looking Ahead

Of course, activity in online grocery, as in the supermarket sector more generally, is still in a preliminary phase.

More accounts of work within the sector are needed to better understand the role technology plays in the everyday experience of the worker, whether it’s as a means of disciplining workers or as a site of resistance. A challenge to workers agitating in the industry is to assess the everyday tactics workers use to make their jobs easier and articulate them into a campaign. It’s hard to imagine a future set of demands for workers that doesn’t include the technologies discussed above as fundamental platform on which to fight.

-

an experience also documented by another Sainsbury’s worker in the Plan C article, Creatures of the Night. ↩

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

author

Adam Barr (@Adambaa13)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Future of Work, Automation and the Left

by

Jeremy Large

/

March 30, 2018