Until recently, young people in England could choose one of three routes into Level 3 (post-GCSE) study: A Levels, applied general qualifications (AGQs), and technical qualifications leading to specific vocations. In the “Brexit budget” of March 2017, chancellor Philip Hammond allocated £500 million of funding for new Level 3 qualifications. In October of that year, education secretary Justine Greening announced that T Levels in digital, childcare and education, and construction would be taught at a small number of providers from September 2020. Greening stated that the full range of T Levels, covering thirteen further specialisms ranging from agriculture to health to transport and logistics, would be available from 2022–23.

“We are transforming technical education in this country,” Greening said, “developing our home grown talent so that our young people have the world class skills and knowledge that employers need.” The existing three routes would be replaced with a two-route model: A Levels and T Levels. The content of the new two-year qualifications would be decided by a series of panels; representatives from industry — including IBM, Fujitsu, and GlaxoSmithKline — were named as chairs for their respective subject areas.

In theory, one T Level is equivalent to 3 A Levels. The courses are split between college-based learning (80%) and an “industry placement” (20%) lasting at least 45 days. Greening spoke of the central role T Levels would play in “giving all young people the opportunity to fulfil their potential”. Education workers and their unions weren’t so sure. In 2019, Kevin Courtney, Joint General Secretary of the National Education Union, criticised the subject panels for their lack of pedagogical experience. More fundamentally, Courtney questioned the scheme’s framing of education pathways: “The NEU is concerned that T-levels could increase the divide between academic and vocational learning”.

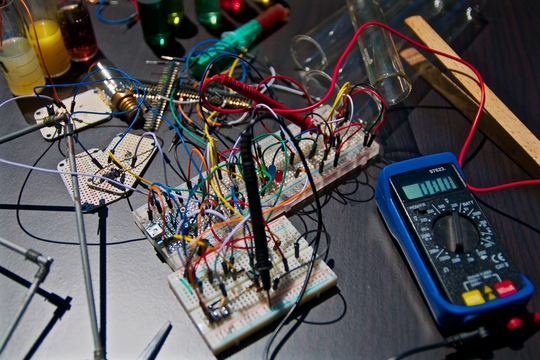

Over 100 existing AGQs are set to be lost — their funding is being removed as T Levels in overlapping areas are rolled out. The Protect Student Choice campaign — a broad alliance of education unions, advocacy groups and organisations — has led the opposition to the government’s plans, making the case that many students will still be better served by studying for AGQs, particularly BTECs. BTECs offer valuable flexibility: they can be completed alongside A Levels or other training, or as standalone courses that can scale up to the equivalent of 3 A Levels (BTEC Diploma). Students can change specialism during the two-year Diploma if they discover a new interest or strength. BTECs utilise a wide range of assessment procedures, with a central role for continuous assessment through assignments, projects, coursework portfolios, reflective practice, and other methods.

T Levels rely on students having a clear idea at 16 or 17 of which sector they would like to be employed in, and offer little to no flexibility. Students can receive a statement of achievement for the elements of the course they have completed, but there is no off-ramp after a year if they want to pursue new interests. Assessment of the new courses relies on high-pressure final exams.

Additionally, for students who, for a variety of reasons, are not successful in their GCSE exams, BTECs offer a clear route from Level 1 to Level 3 study, and then on into employment, further education or training, or university. In the latter case, they have been particularly important for groups that historically have been excluded from higher education. Universities began accepting BTECs for entry in the early 2000s as part of New Labour’s widening participation agenda. A 2018 study by the Social Market Foundation found that 37 per cent of Black students enter university with only BTECs and that nearly half of white working-class students admitted studied at least one BTEC.

The pandemic has undoubtedly made things more difficult, and has resulted in a series of delays to the scheme, but it’s likely that T Levels would have been a mess even without the intervention of the novel coronavirus. The removal of BTECs and other AGQs has drawn fierce criticism, not least after the Department for Education’s own equalities impact assessment concluded that “Those from SEND [special educational needs and disability] backgrounds, Asian ethnic groups, disadvantaged backgrounds, and males [are] disproportionately likely to be affected.” In January, a cross party group of peers criticised ministers for reneging on promises that many existing courses would be retained.

The government clearly expects existing staff in sixth form and further education colleges to make T Levels a success — but workers at these institutions are already at breaking point after more than a decade of pay cuts and underfunding. The Association of Colleges, the membership body that represents colleges across England, recently took the unprecedented step of refusing to make a pay recommendation for the 2023–24 academic year. “This is not because we don’t think staff deserve a pay increase — we do — ” chief executive David Hughes wrote in a letter to education secretary Gillian Keegan, “but because colleges simply can’t afford to make a meaningful offer, and to continue to recommend small percentage pay rises in line with college funding would be an insult to the hard-working college staff.”

In May 2022, it emerged that just 14 percent of those who had completed the T Level Transition Programme, a one-year bridging course for students who didn’t achieve the required GCSE grades, planned to progress to the full qualification. Overall intake figures for 2022–23 were lower than the government would have hoped. A report by Ofsted published in July noted that “the number of students who progress to the second year of T-level courses is low in many providers.” In “at least one provider,” no students progressed to the second year.

Alongside a general lack of clarity around the qualifications, one factor behind the low take-up and retention rates seems to be that in many places, the industry placements heralded as the defining feature of the new qualifications have not materialised. The T Levels website describes the placements as a reciprocal relationship: “Students get valuable experience in the workplace; employers get early sight of the new talent in their industry”. But with little to no central coordination of this part of the qualification, providers have been left to fend for themselves. Education researcher Dr Nuala Burgess has spoken of a “lecturer with a mate” system, with placements called in as personal favours rather than lasting partnerships between providers and employers.

“Experience shows us that employers do not step up to the plate when asked to provide opportunities for young people in the workplace,” Kevin Courtney had warned in 2019, “There are also many areas of the country where there are not enough employers near to colleges to accommodate all learners.” In February, the Department for Education announced a £12 million placement fund to cover employers’ costs. But the fund can’t conceal a more fundamental truth: the new scheme is simply being layered over existing regional inequalities, apparently with little thought as to how they might impact students’ ability to complete their courses. Rather than helping to solve the nation’s pressing structural challenges, as the government promised, in many places T Levels just serve to highlight them all the more starkly.

The extent to which T Levels will offer students a route into higher education — something that the government is now talking about, having not originally been a focus — remains unclear. For 2022 entry, more than half of universities would not accept T Levels, a figure that has fallen only slightly for 2023. Several institutions have expressed concern that the narrowness of T Level curricula will not prepare students for university-level study.

Qualifications are ideological tools, not neutral measures. T Levels and the reckless scaling back of AGQs can be understood in significant part as the Tories’ response to, and attempted correction of, Tony Blair’s 1999 pledge that 50% of young adults would progress to university study, an aspiration that was realised in 2018–19. The branding of T Levels is clearly intended to frame them as equivalent to A Levels. But it also lays bare the class politics that underpin the scheme, with its narrowly conceived education system in which “technical/vocational” and “academic” education are two flowing channels whose waters should not meet. After the fragile gains of New Labour’s widening participation agenda, the Tories’ message to the working class is unambiguous: know your place.

In this vision, the children of the middle and upper classes are still largely encouraged to pursue their academic interests through A Levels — reformed by Michael Gove in 2014 to re-prioritise final exams over coursework — and then at university. The study of humanities subjects like Classics and English Literature and the creative arts are, to an even greater extent than is already the case, to be the pursuits of the rich. Young people from working class backgrounds are to be funnelled towards T Levels and then, if they’re lucky, entry-level roles. Justine Greening’s comment about students “fulfil[ling] their potential” is true only in a very limited sense: their potential to enter the labour force as maximally exploitable employees.

Under capitalism, it has always been the case that the broad purpose of an education system “is to produce the next generation of workers (and in particular cases, bosses), as well as managing surplus populations until they are of an ability to join the working population”. Yet the period since 2010 has seen “industry” and “business” given ever more central formal roles in education policy, and the right’s market fanaticism extend to almost every corner of the education system. Education is framed solely as preparation for work and students are compelled to see themselves as investors making down payments on future earnings. The privatisation of thousands of English schools under the banner of academisation — a barely-concealed asset-stripping scheme that has enabled private individuals to enrich themselves on public money, and which sees thousands of students subject to authoritarian and regressive control pedagogies — sits at one end of this process. The decimation of adult education — with its broad suite of courses that offered opportunities to pursue intellectual curiosity and creative expression, and that did not fit a narrow employability agenda — is at the other.

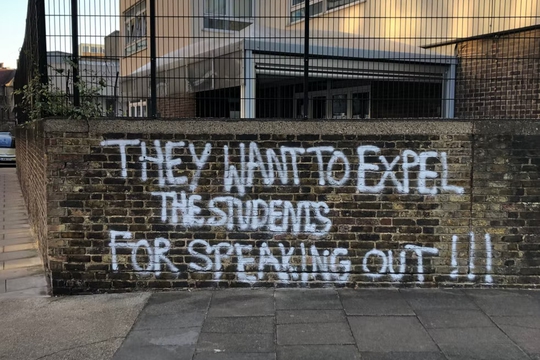

The narrowing of the scope of education has of course been accompanied by changes to how institutions are conceptualised and run, with disastrous results for many workers and correspondingly good results for their senior managers claiming six-figure salaries. The marketisation of universities draws most attention, but sixth form and FE colleges have seen similar changes. Many colleges are managed by a self-styled “Principal/CEO”. Staff at Newham Sixth Form College recently began thirty days of strike action over staff cuts and management conduct and decision making; “we are not a business in Canary Wharf and the leaders cannot run this place as a corporation” one striking staff member said.

We can understand the controversy around T Levels as both a culmination of recent trends and as the latest iteration of a much older, bigger question, one that should be central to any left political project: what would a humane and emancipatory education system look like? Keir Starmer’s recent ditching of his pledge to abolish university tuition fees takes Labour another step further away from the 2019 manifesto and its ambitious plans for a National Education Service (NES). With its vision of lifelong and modular learning, free for everyone, the NES would in time have entailed much more than the restoration of funding lost since 2010: the move away from linear “vocational” and “academic” post-16 pathways and the educational and social segregation they entail; the gradual dissolving of the artificial and regressive distinctions between further and higher education, and between “vocational” and “academic” pathways; opportunities for everyone to explore the creative arts.

The NES also provided a way to articulate the place of education reform in relation to other aspects of a more equal and democratic society: work and free time, social care and childcare, public transport, housing, free public utilities (broadband especially). In other words, the NES prompted usefully reciprocal questions — not only “what would this system look like?”, but also “what kind of society would it require and entail?”

That moment has passed, for now, and workers across the UK education sector are fighting for a liveable wage and decent working conditions. Imagining an education system that would do justice to the students who we see each day remains a necessary and invigorating task, though. And in my experience, when workers do go on strike, this is where the picket line conversations usually turn.

author

Tom White

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Kids Are Alright: A School Workers’ Inquiry

by

A group of school workers

/

April 24, 2024