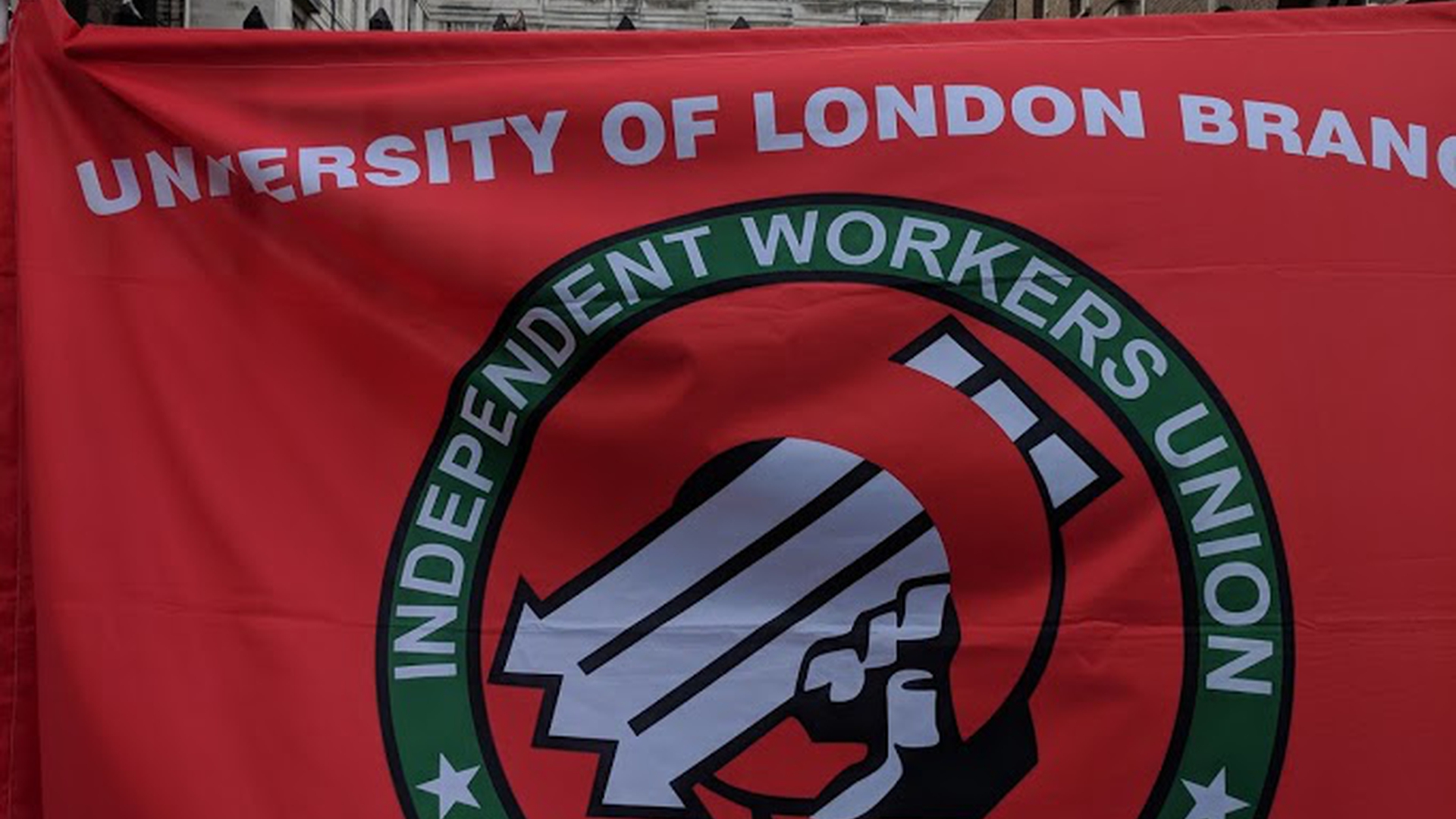

Support the IWGB Boycott

At Notes from Below, we have covered strikes and campaigns in Higher Education in the UK, as well as running The University Worker bulletin during the UCU strike. Throughout the UCU campaign, we argued that academics should get involved with worker campaigns on campuses. Sai Englert and me recapped the history of UCU as we prepared for the latest ballot over pay.

We argued that the IWGB campaign and strikes to bring outsourced workers back in-house pointed towards another model of how trade unions could fight in universities. Our article finished by arguing that “we look forward to a new term of strikes, in which the lessons of last year can be applied by a more experienced and mobilised membership, but - when reflecting on last years’ missed opportunity, we still look back in anger.”

When the ballot was announced in October, the results fell below the 50% turnout required by law. This meant no academic worker strikes for the next term. We still look back in anger at UCU – as well at the members who now decided pay was not worth fighting over. But that anger is not something that academic workers should just channel into internal fights with the UCU bureaucracy.

The university is made and remade by much more work than just that of lecturers and professors. The academic workplace relies on undervalued and underpaid workers, often not present in these national UCU campaigns. These conditions are no accident. The leadership of universities have chosen to outsource workers to try and cut costs – as well as pushing workers into conditions they would find it hard to justify on their own books.

While academics have gone on strike over pensions, as well as trying to do so over pay, there is much more action needed in universities. Our workplaces continue to be transformed through damaging government policies and the decisions of senior management. This is resulting in universities that are increasingly inaccessible to students, who become burdened with unsustainable debt. For the workers upon which both academics and students rely, universities are becoming increasingly hostile and exploitative workplaces.

At the University of London, outsourced workers have much worse terms and conditions than those who are directly employed. This affects holiday pay, sick pay, maternity pay, and pensions. This also means that they have to negotiate separately than workers who they work alongside. In addition to this, the outsourced workers are treated far worse by management, with over twenty-five times the number of complaints of bullying and harassment compared to in-house workers.

The IWGB has highlighted a pervasive culture of bullying by Cordant (the outsourcing company). This includes a manager who was a supporter of the far right assaulting a migrant worker and another manager accused of three complaints of sexism and homophobia. These managers have continued without being held to account.1 This is no accident, but the result of outsourcing. It allows managers to act in ways that the direct university management would otherwise be held accountable for. If either of these happened to academic workers or students there would be outrage on the campus, and the university management would be forced to respond.

These outsourced workers have shown what a militant fight looks like on campus. The workers have been on strike repeatedly, including many of them having more strike days than the UCU campaign. However, despite the strikes, protests, and solidarity actions, the university refuses to negotiate with them. Rather than entering into dialogue, management have spent an estimated £500,000 in two months on extra security to try and break the strikes. They transformed the university into a cordoned-off zone, and at the last strike, the university brought in bailiffs equipped with handcuffs and extendable batons.

While management initially committed to ending outsourcing, the university has now said that cleaners will remain outsourced until 2020 and catering until 2021. There will then be a tendering of in-house options alongside commercial bids. This is unacceptable.

While academic workers might not be taking their own strike action this year, the IWGB campaign is something we should all be throwing our (relative) power in the university behind. While we have tried to fight over pensions and pay, it is now time to take action on what kind of universities we want to work in. While there are many fights we could (and should) take on for this, signing and sharing the pledge below is a good start:

I pledge to not attend or organise any events at the University of London central administration (including Senate House, Stewart House, the Warburg Institute, the Institute of Historical Research, the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies and Student Central) until all outsourced workers (including cleaners, receptionists, security officers, catering staff, porters, audiovisual workers, gardeners and maintenance workers) are made direct employees of the University of London on equal terms and conditions with other directly employed staff.

Academic workers need to start taking seriously the struggles of other workers on campuses, as well as thinking about how our role supports or undermines them. The failure of the ballot was a major set back, but it is not the only way we can use our workers power on campus.

You can find more information about the boycott here, and sign the pledge here.

-

The manager who assaulted a migrant worker was later removed after his links to the far-right were revealed, but there is no information about whether he was dismissed or continues to manage workers on other Cordant sites. ↩

author

Jamie Woodcock (@jamie_woodcock)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The University Worker Week 1

Feb. 21, 2018