Struggle and Vulnerability in Portuguese Call Centers during the COVID-19 pandemic

inquiry

Struggle and Vulnerability in Portuguese Call Centers during the COVID-19 pandemic

by

Isabel Roque

/

June 24, 2020

A report from a call centre in Portugal

In early March, when the first cases of COVID-19 were starting to appear in Portugal, call center operators felt threatened for their lives in their workplaces, as the companies did not take enough action concerning health and safety measures. Healthy workers were placed in the same open space rooms as the ill, and those who had recently returned from abroad, even from countries with severe outbreaks, were not subjected to any quarantine or isolation procedures.

This situation is very serious, since workstations and tools, including computer, mouse, headphones, screen, and keyboard are shared daily and are not adequately cleaned between uses, enabling the transmission of viruses, skin diseases, and allergies. Cleaning materials, such as disinfectant, detergents, alcohol gel, toilet paper, and masks were very scarce or not distributed. In one call center in Northern Portugal, the cleaning staff was forced to use only water. There tends to be a low number of bathrooms and elevators for each employee, in the open spaces workers operated side by side, and in some cases companies removed chairs from their canteens but kept them functioning. It should be noted that these companies frequently try to omit health hazards, as well as COVID-19 infection cases.

Given this situation, and due to the fact that call center buildings tend to be located in cities with greater incidences of the virus, it is no surprise that these workplaces became hotspots of the pandemic. In fact, Portuguese call center workers were forced to keep commuting to work during the pandemic.

For years, call centers in Portugal have been struggling with safety and hygiene issues, occupational diseases, and accidents, thus constituting one of the chronic problems of post-industrial societies. In terms of architecture, call centers can take a number of forms, ranging from call centers installed or attached to garages, and shops, to buildings where work is carried out in open space. More broadly, there is a lack of infrastructure for older workers, as well as for those with reduced mobility. Cleaning also tends to be casualised, and be performed during working hours, i.e., when the worker is answering a call. Air conditioning systems are not properly adjusted, or cleaned, or replaced when needed, leading to respiratory and pulmonary diseases; windows are usually closed, and lighting is often artificial and/or insufficient; tables must only contain a sealed water bottle, a ballpoint pen and a notepad; workers also often face excessive noise due to the high number of operators working in the same room. Each service station is only separated by screens and devoid of any privacy. Every week a map is designed with random places allocated to each operator to ensure that there is no talk during work, and that no trace of familiarity is established between workers. According to the Portuguese Association of Contact Centers (APCC) 1 there are 100,000 operators who provide information and sell products, goods and services through customer support lines and supply services, using digital platforms, phones, email and instant messaging.

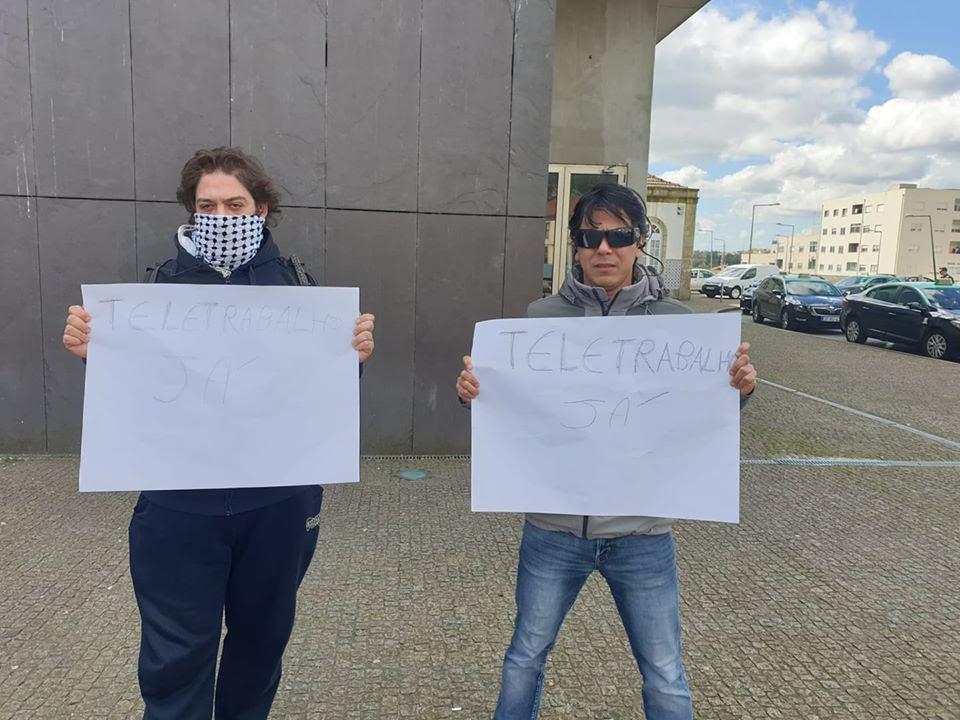

Call center workers hired from Randstad, who offered technical support to the NOS call center service, have long been fighting against precarious working conditions, demanding safety and hygiene, the restitution of performance bonuses, long-term contracts for anyone who has worked for three years, equal rights regarding food allowance, and, most of all, the end of moral harassment with more demanding services and changes in weekly schedules. Besides the refusal of a negotiation process presented by STCC to Randstad, nothing was done regarding this situation. So, on March 10, call center operators alongside the Call Center Workers Trade Union (STCC), the only Portuguese trade union specific to call centers, went on strike. Workers on a 90% rate of participation, alongside with STCC, marched in the streets of Coimbra for one day, echoing loud protest voices. Not only was the strike successful in terms of its participants, it was also able to transition some workers into teleworking.

Nevertheless, with the COVID-19 pandemic, call centers in wider Portugal were becoming sites of contagion. On March 12, STCC issued a statement,2 with the support of other trade unions and various activists, proposing a set of measures to help solve the COVID-19 call center crisis. It aimed to stop all non-essential sectors with full wages and guaranteed rights in defense of public health, rather than putting the health of millions of workers at risk for the sake of profit. Nevertheless, APCC certified that the vast majority of call center companies (NOS, Teleperfomance and Armatis-LC) were already transitioning to telework in order to protect their workers. In reality, this was not true. Teleworking was only available for the human resources department, the company’s board, and certain supervisors. Call center operators continued to work onsite, fearing the loss of their health or the loss of their jobs. Most workers only got information regarding COVID-19 measures by demanding it from companies.

As a consequence, all these situations were denounced by workers to trade unions, especially to the Call Center Workers’ Union (STCC), which reported it to the national and international media, such as Reuters,3 and to the different parliamentary groups, and asked the Health Ministry and the Authority for Working Conditions to carry out health inspections.

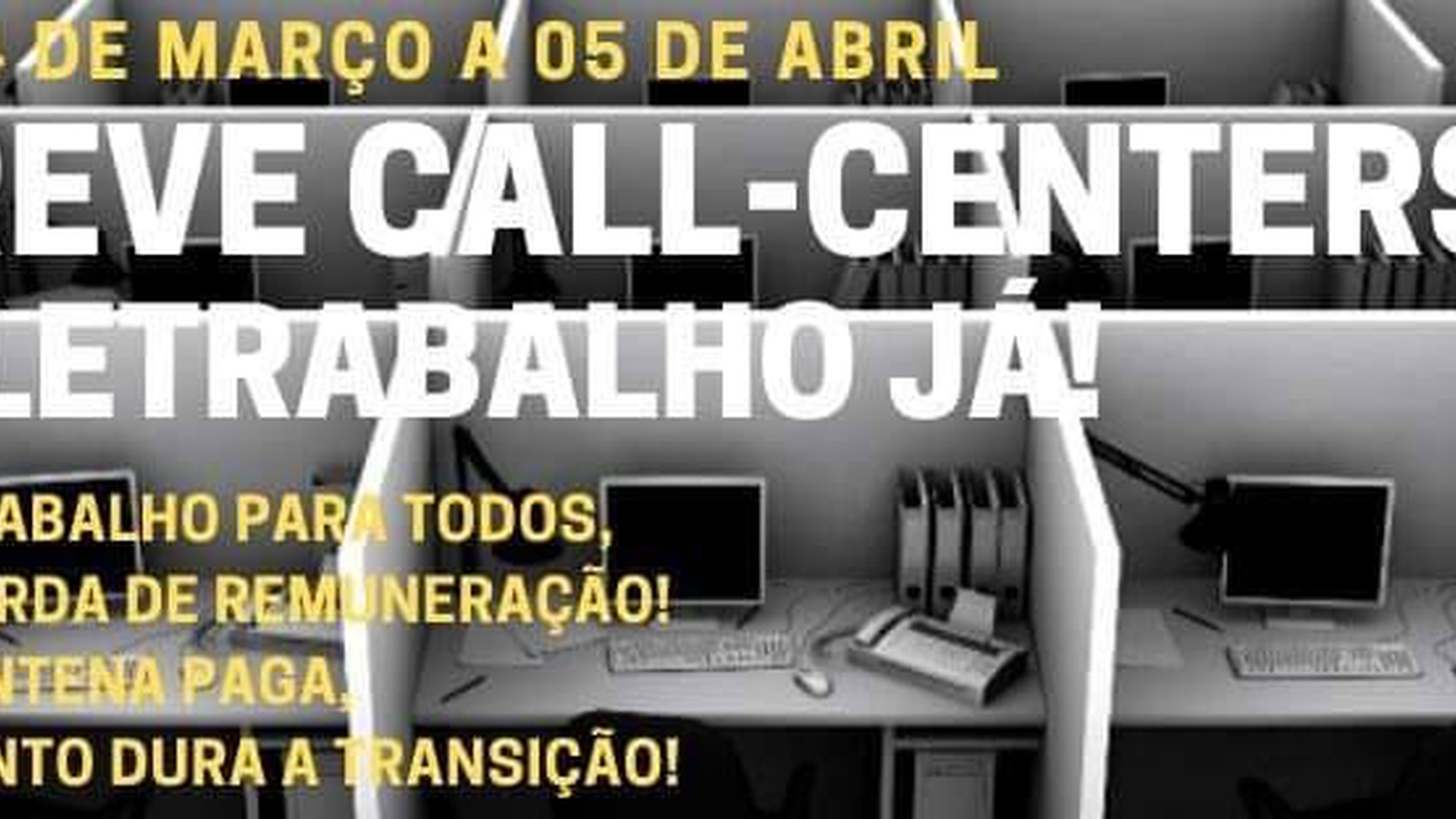

It was in this context that, on the 20th of March, STCC called for a nationwide strike to take place between March 24 and April 5. It demanded special legislation for the call center service regarding the transition to teleworking, without loss in workers’ remuneration. Furthermore, call centers where several cases were detected, such as Teleperformance, would be forced to close after inspections took place. According to STCC this could only be done through pressure, through the paralysis of production affecting companies’ profits. STCC also created, and disseminated through their website and Facebook page, a model for the denunciation of bad practices during the Covid-19 period, written in in several languages, as well as an online petition[^4, so that workers in non-essential public services could immediately be transitioned to teleworking. This situation also led to a widespread revolt in call centers at a national level, manifesting high rates of class consciousness amongst workers, with absences from work, sick leave, vacation requests, and refusal to log in at several workplaces, especially BNP-Paribas, Teleperformance, NOS and Armatis-LC, demanding an immediate transition to teleworking. As a result, the majority of call centers informed their workers that they would proceed immediately with the transition to teleworking.

According to the Decree Law 10-A/202, call center work comprises all the possibilities of transition to teleworking, and since the state of emergency had been decreed, this situation should have immediately been put into practice. The role played by STCC was crucial, reinforcing and accelerating this process. According to Danilo Moreira, STCC’s President, the results of this strike were quite positive for the majority of workers. In fact, this could become a turning point regarding hygiene and safety matters for the call center universe, if regular inspections continued to be carried out on a regular basis, not only in situations of a pandemic. However, days after the strike ended, there were still companies that had not fully converted their services to teleworking, alleging that they lacked VPNs. Others engaged in threats, in moral harassment to workers who had transitioned to teleworking, sending dismissal letters to workers who had weekly and monthly contracts, and in other situations opting for layoffs. Danilo Moreira was one of the victims who was dismissed from the Altice call center where he had worked in the outbound service on a weekly basis for the past 10 years. He was sent into training before the pandemic started, and after that the company decided to place him on furlough for a month, before dismissing him. He received the letter a couple of weeks ago, very surprised, for he was one of the best workers the company had, besides the respect he had gained from the board for being a trade union leader. Nevertheless, he stated that the struggle was not over and that he would fight until the end with the help from the union’s attorney.

There were also issues related with the expenses inherent to the worker, such as the costs with adequate furniture (chairs, tables, computers), internet installation, electricity bills, and the loss of food allowance. STCC informed all its workers, especially on social media and through virtual workers’ assemblies, that they were entitled to all of that. Certain attempted Orwellian impositions were made by certain companies, like demanding the installation of a webcam at the worker’s house for performance control. STCC managed to challenge this policy, and in the end it was only applied for workers who lived in rooms made available by Teleperformance.

Now that the state of emergency has been lifted, several call center companies are planning to start calling their operators back to work during the months of June and July. STCC has asked the government and the parliament to legislate in order to prolong teleworking for call center services until September, before taking any decisions or giving in to the pressure from the multinationals that run the sector. Nevertheless, according to Danilo Moreira, the majority of workers want to keep themselves safe through teleworking. Call centers can involve dozens of workers in the same room, using the same bathrooms, elevators, and canteens without respecting social distancing, heightening the danger of contagion. Even the wearing of masks while answering calls can be very complicated, especially for people who suffer from respiratory problems, creating a bigger vocal wear due to effort while speaking, or merely want to take a quick sip of water during 8-hour shifts. According to STCC’s President, if call centers reopen during June and July, it would be a tremendous irresponsibility, capable of leading to the rapid proliferation of the pandemic, creating new hotspots. On May 27, STCC had a virtual meeting with APCC board members regarding this situation. Apparently, it was well understood, keeping the promise of explaining these questions to all of the call center companies that they comprise, also assuring that physical return to work will be progressive and slow, keeping all the safety and hygiene, as well as social distancing measures required by the Health Ministry. Nevertheless, call center companies always tend to see the bright side of the situation, but the fact is that some companies, like Altice, are dismissing their workers or forcing them into teleworking, while investing in 5G technology, even if they insist that they are very concerned over their workers’ health and well-being.

Nevertheless, call center companies are also starting to see major benefits from teleworking and are already trying to impose this regime on the majority of workers, asking if they want to remain in it on a long term basis, even when there isn’t proper legislation regarding that. This can also bring several other problems, increasing vulnerability to exploitation and isolation from work colleagues, leading to serious problems in the realm of unionization and social struggle.

Throughout the pandemic, STCC’s role has been remarkable, not only creating new strategies, especially virtual ones, and making tools available for them to struggle, but also in standing with workers in the battlefield, not to mention the denunciation of cases of non-compliance with hygiene and safety conditions at work. In addition, STCC continues to gather through virtual plenaries with their associates and non-member workers, not only in order to gain more affiliates and gain their trust, but to discuss the implementation of teleworking, address workers’ rights, and, most of all, to discuss struggle strategies, with the help of their attorney and sociologist.

In a pandemic scenario, labour exploitation continues to affect all professional sectors, threatening human life, through imminent dismissal, placing workers in situations of vulnerability, but also through poor safety and hygiene conditions at work, placing life itself at risk. Amidst this scenario of exploitation, working the phones is not even considered a profession by the Portuguese National Classification of Professions, leading to the lack of recognition as a part of the working class, remaining socially unprotected in work, and in unemployment, for the sector does not have specific labor regulation. The presence of temporary work agencies is also a crucial factor for the increase in poor working conditions, especially when an operator can be working for several companies in one day and still have a weekly or monthly precarious contract, which only renews itself according to daily and demanding tasks, surveilled by the second through machinery and a virtual panopticon.

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated the vulnerability of call center workers, where they had to choose between fighting against precarious health and safety conditions, or to stay working in unhealthy call centers waiting to die from COVID-19, or any other virus that the future may bring. Nevertheless, this situation has also shown how call center workers can still gather towards class consciousness and stand up together, organized through trade union guidance, and reclaim their true power on the call center assembly lines.

Videos of the strike

Greve Sindicato dos Trabalhadores de Call Center tás logado 24 de Março a 05 de Abril de 2020

Greve do Callcenter da NOS Randstad em Coimbra 10 03 2020 V 1

Greve do Callcenter da NOS Randstad em Coimbra 10 03 2020 V 3

author

Isabel Roque

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

In Morocco, they go to work with fear in their bellies

by

Rosa Moussaoui

/

April 28, 2020