Strikes in the Time of Coronavirus

March 19, 2020

Reflections from a University Worker

inquiry

Strikes in the Time of Coronavirus

March 19, 2020

Reflections from a University Worker

This article is a contribution from a university worker and UCU member. It aims to start a discussion about how workers across different industries can best respond, in a coordinated manner, to the unfolding coronavirus crisis, without forfeiting our collective power. At Notes From Below we welcome other contributions from workers and activists on this topic and we hope this piece will serve as the starting point for a wider debate.

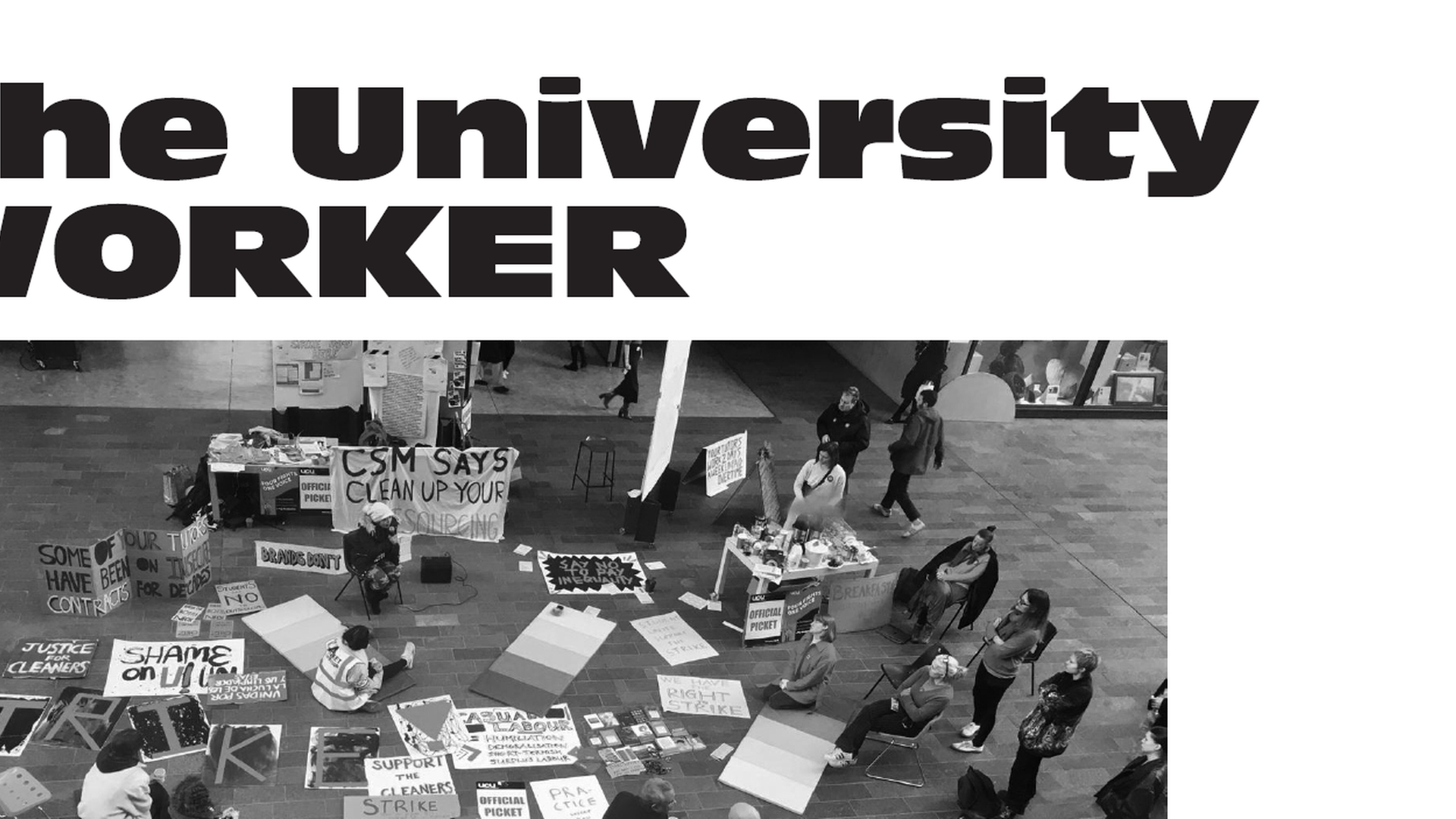

The coronavirus outbreak will transform our lives in unprecedented ways, not least in the workplace. For members of many unions and workers’ movements, it also occurs in the midst of major industrial disputes. UCU remains locked in a battle with employers over pensions, pay, conditions, and equality, with some branches still taking strike action as late as Friday 20th March. The CWU has just won a resounding vote for strike action in a reballot in its dispute over conditions and the future of the postal service. Unite workers at the homelessness charity St Mungos went out on strike from 16th-18th March. Other local disputes continue, such as the planned strike involving both UNISON and the NEU in Tower Hamlets, who together represent thousands of workers in schools and local government. But what does coronavirus mean for these struggles? Is it possible to remain on strike in the time of coronavirus? What role can trade unionists have in fighting the virus? Or, in other words, what does the coronavirus crisis look like from below?

The government has made extensive use of the rhetoric of national unity, national effort, and “working together” in their response to the crisis. Invoking a wartime spirit, they call upon the public to make huge collective sacrifices to help save lives and reduce the burden on the NHS. From the point of view of workers’ inquiry, such claims about national unity should always seem suspicious and dangerous. Indeed, some employers have cynically deployed such rhetoric as an argument for suspending or ending strike action, as the Provost of UCL did in an open letter to UCU this week. Acceding wholesale to such demands and retreating from our struggles “in the national interest” would be a mistake. Of course, coronavirus means that our strategy cannot continue as it was before, or even with minor adjustments. The disease will transform society, the economy, and the public realm - the very terrain on which we are fighting to defend ourselves. It would be foolish to think we can carry on even remotely as we were. But calling for the transformation of our strategy is not the same as calling for the abandonment of workers’ struggle. In fact, such struggles are more vital than ever, and it is our urgent task to rethink how they can be reshaped and continued.

Faced with demands to de-escalate, some unions and individual members have decided to respond to the crisis by dialling back, postponing, or even abandoning their strike action. These decisions have sometimes been sensible, and sometimes have not, but they have so far not been coherent or properly co-ordinated. Instead, the responses have varied by sector and up and down the bureaucratic hierarchy. Leaders of the large unions, such as Len McCluskey, have sent out co-operative signals to the government, asking to be included in discussions about protecting workers. UCU’s Higher Education Committee postponed its planned reballot, cancelled remaining rallies and in-person pickets, but called for strikes and action short of a strike to continue. The CWU has said it will delay its planned strike action and instead offer to become “a fourth emergency service” in this time of crisis. Meanwhile, rank and file members and lay officials across many unions have engaged in extensive discussions about whether and how to continue with strike action. For example, Queen Mary UCU voted in a partially electronic branch meeting to continue with its strike action from 16th-19th March and to send out messages of solidarity and guidance to students and the wider university. By contrast, the branch committee at Birkbeck University of London put out a statement calling the continuation of strikes “at best pointless and at worst counter-productive”, and encouraged members to make up their own minds about whether to continue.

The necessity for workers to keep up their pressure on employers and the government should be obvious from the way they have so far responded to the crisis. While they have deployed the rhetoric of national unity, it is clear the burden of their response will fall disproportionately on workers and the poor. It emerged that the government’s original plan - to allow the disease to spread slowly but to mitigate its impact - would have resulted in 250,000 deaths, especially of the older and more vulnerable, and the likely collapse of the health system, precisely as the WHO and other scientists had warned. This left staff at schools and universities increasingly worried that they were being told to continue working as part of a plan to gradually expose them and their families to the disease, with potentially disastrous consequences. Typical to form, rather than pushing back on behalf of worried staff, several university leaders insisted that campuses should remain open as normal as per government instructions.

The new plan for “suppression” of the virus will have other drastic impacts on workers. The impending closure of many workplaces, including bars, pubs, restaurants, will leave many workers in a precarious financial position, and perhaps without jobs. Key workers, such as frontline doctors and nurses, warehouse staff, or delivery drivers, will be asked to work unprecedented extra hours. Eventual school closures will lead to a huge increase in the burden of childcare. University staff have been asked by managers to shift rapidly to online teaching with little to no extra training or support, especially for the large and growing number in precarious and poorly paid positions. So far, the government’s economic response has been to announce mortgage holidays, but not rent relief; to encourage self-isolation, but to leave statutory sick pay at its dismally low level; to give grants and bailouts to companies, but not adequate benefit increases or basic income guarantees. Employers have often left it up to individual workers to decide whether they can afford to self-isolate; others have simply not allowed it.

It should be plain from the above that the rhetoric of national unity and working together is hollow. If we flatly give into demands for industrial peace and national unity we will risk exposing ourselves to more suffering and exploitation, and we should not expect good will in return. The reason for the government’s change of course from “mitigation” to “suppression”, as many had been demanding, does not come from a concern about the wellbeing of ordinary people. After all, a reputable study in the British Medical Journal showed that the austerity policies pursued by successive Tory governments have already resulted in 120,000 additional deaths among the poorest and weakest in society. Rather, the government is worried that the sudden increase in sickness will cause production and circulation to collapse, markets to panic, and the public finances to be overwhelmed. In other words, the government has changed course because it recognises that it needs us to keep working and producing value, much of the proceeds of which we will never receive.

But this realisation also gives us leverage. It is no coincidence that World War Two, the rhetoric of which we are hearing constant echoes, was followed by the creation of welfare states and huge injections of foreign aid into Europe from the United States. Governments knew the sacrifices that working people had made, and knew that workers were well organised enough to extract gains in exchange for military service, political quiescence, and industrial peace. They were forced to buy workers off. There are of course no guarantees at all that similar gains will follow automatically from the coronavirus outbreak. Today’s labour movement is much diminished, the era of mass social democratic parties appears over, and the distribution of imperial power and wealth in the world has changed beyond recognition. But there are still ways in which we can protect ourselves, look after each other, and secure victories in our ongoing struggles with employers and the state.

The response of ordinary people to the crisis suggests that many already implicitly understand this. These responses give indications of what our strategy going forward could look like. After the government’s initial decision to hold off on school and university closures, absenteeism among staff at schools increased, making closures more or less inevitable whatever the government’s plans. Likewise, university staff pushed back through their local union branches against the demand to continue working, forcing employers into making concessions on home working. Some are also using the strikes or action short of a strike as cover for refusing to rapidly move classes online as university managers wanted. These concessions have often been piecemeal and small, but they indicate a possible pattern for taking matters into our own hands.

Beyond the workplace, a network of mutual aid groups are springing up in communities, often organised through social media, to bring supplies to older and vulnerable people or to households who are self-isolating. If these initiatives are successful, they could give people crucial breathing room in their decisions about whether they can afford not to work to protect their health or care for loved ones. Such safety nets can also give more confidence to people making demands on their employer and the state for flexibility and further support. Whether these networks of mutual aid can be developed and maintained will be crucial for both defeating the virus and surviving the outbreak. Workers and trade unionists could have an integral role to play in creating and sustaining them. The postal workers, as the CWU has suggested, are especially well placed, but other workers could just as easily join in. Skills from workplace organising could be crucial here. Operating pickets is, after all, primarily a task of getting people and material in the right place efficiently and safely. Furthermore, contacts made on recent university campus pickets have already been the basis for starting and publicising mutual aid initiatives.

However, workers will only have the ability to help deliver mutual aid effectively if they have sufficient time for it and if it is organised democratically. If matters are left in the hands of employers, they will always be more concerned with increasing overtime and maintaining their core revenue generating activities than giving workers time for mutual aid. At this moment helping each other is far more important than whether business mail is delivered or whether university lectures continue online. This is where workplace organising, including strikes, rather than being a distraction, could have an important role in how we fight the virus. If workers are on strike but not congregating on picket lines for health reasons, they are well placed both to look after themselves and assist in mutual aid efforts. Even where workers are not on strike, unions can still be crucial vehicles for applying pressure on employers to grant the flexibility and free time we need to focus on looking after each other in the months ahead. Unions should take this into account when considering whether and how to conduct their strikes and what they ask striking members to do while not at work, and they should help to coordinate mutual aid initiatives across the country. This approach would not only allow us to continue to gain leverage over our employers, but could also improve the response to the virus and place it back into the hands of ordinary people.

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

It's time to close our schools

March 16, 2020