Social-Distancing and Alienation

inquiry

Social-Distancing and Alienation

by

Enzo

/

April 19, 2021

Working at Amazon at the height of the pandemic, part 2

This is the second of a two part piece. You can read the first part here.

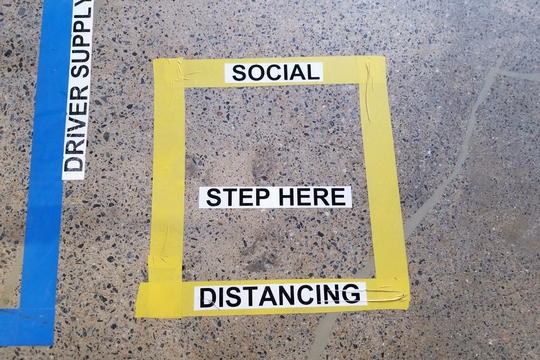

One of the most common grievances at Amazon was directed at their social-distance policy. With this in place, everybody was separated. Where you might normally expect a large workforce to be divided into groups based on age, race, gender, or other shared identities, here everyone was divided from everyone else. At first, these restrictions were disorienting. Keeping two-metres from others prevented almost all basic human interaction, with huge plexiglass sheets separating everyone in the canteen at break times, like a prison. On the floor was another story. To work side-by-side with masses of other people, in a type of work that necessitates moving all around the warehouse, and to maintain this distance at all times – this is a difficult art. Crammed in narrow aisles with many workers coming and going as per the necessities of their tasks, it becomes impossible.

Amazon enforces this policy, ostensibly for the protection of workers, through disciplinarian “social distance ambassadors”. These “ambassadors” are given a large stick with all kinds of warnings on it which they hold in the air, and their job is to police the workforce, issuing red-cards, verbal warnings, and constant reminders to workers to keep away from one another. Cries of “keep your distance!” and “two metres!” echoed constantly in the warehouse. It is difficult to convey the pressure this exerted on us. Labouring away each day, all day, for up to 10 hours, with these people constantly screaming at everyone – it was unbearable. Workers would put their hands over their faces, struggling to cope with the realities of the place. To be issued a red-card could mean a serious meeting with a manager, or worse, the sack.

“Social distance ambassadors” became despised by workers. Some of them were managers, others were selected from amongst the workforce. One of these workers told me “it’s not in my nature to do this. I can’t speak to people the way they expect me to. It’s horrible.” These kinds of workers, who showed respect and solidarity, were quickly replaced with those who adopted an aggressive attitude. One of these “ambassadors” would discriminate against particular workers, mocking and teasing them, following them around and threatening to report them for not working fast enough or for not listening. They would antagonise workers who had stopped for a moment, taunting them. “Are you deaf, eh?”, they would say, refusing any constructive dialogue. One co-worker told me they had been called “fucking idiot” by this person, and others were accused of being lazy whilst they were working. After workers reported this behaviour, they told me that managers had trivialised the situation and refused to do anything. This enforced the real ideology inside Amazon, with its cult of super-work and disrespect. “Social distance ambassadors” were managers’ lackeys, convenient tools for disciplining the workforce. Despite frequent complaints of bullying behaviour, managers refused to do anything. One manager told us he would not even accept complaints against particular “ambassadors”. By preventing workers from reporting grievances, we were exposed to discrimination and intimidation. In this way, the “hell” I was introduced to on my first shift gradually began to make itself felt, establishing a uniquely Amazon imprint on the day-to-day experience of work and alienation.

Health and Safety Against Workers

Everyone who has spent more than a few weeks inside Amazon knows very well that the company does not take health and safety seriously. It was only serious about how it could appear to protect workers. This was evident in how we entered the building every day. Temperature checks were introduced as a Covid-19 protection. They were supposed to be enforced at the entrance every day, but this was set up in an extremely poor way. There was no need to stop and you could just walk past the device. It was often altogether ignored: one time, a manager urged me to keep a special distance away from them, as they themselves had been flagged with a high temperature, and yet still let in.

A constant influx of new workers meant the queue to clock-in and use lockers grew in size. Cameras would pick up on this growing queue, and senior managers would not be happy with the failure to enforce the social distance policy. As a solution, managers on the floor simply changed the queuing locations to hide them from the view of the cameras, even though this made things more difficult for workers. “Officially”, there would be no breaches to report. It was all representation, all box-ticking, all bullshit. Similarly, Amazon’s facemask policy was employed selectively by managers. Everyone had to wear a facemask at all times. One worker, I was told, was sacked for having his facemask slip below his nose one too many times, a common occurrence that is sometimes unavoidable in the heat of the work. In the same environment, particular managers would be seen walking around on the floor with their own masks lowered, stuffing their faces full of sandwiches. This kind of blatant double-standard and trigger-happy sacking power - and at the height of a pandemic, no less - was repulsive.

Health and safety was weaponised against workers. It was used as a tool for disciplining and manipulating labour, attempting to produce a kind of docility and obedience. Just as there was a process for sorting and circulating commodities inside the warehouse, so too was there another process - just as important and essential to Amazon – of demeaning human beings. Through the use of employment agencies and zero-hour contracts, Amazon attempts to engineer their perfect workforce: an unquestioning mass of workers who do not and cannot raise grievances. Agency workers who spoke up about problems were seen as trouble-makers who wanted to disrupt Amazon’s service, and could easily be fired. In this way, Amazon implicitly accepted a model of work that treated workers like cheap raw material to be used up, as if from a quarry or a mine, to be battered and moulded to their liking. With the pandemic creating so much unemployment, Amazon could take advantage of this. For every worker fired there were more out of work and needing to earn a living. It was incredibly difficult to complain using official channels, as managers just dismissed agency workers’ concerns. Retaining your dignity was important in this demeaning environment. However, workers who stood up for themselves and spread some joy in a miserable environment were often sacked for one reason or another, for “talking back” to managers or telling them where to go.

One day, an operations manager pulled every worker in for a meeting to discuss the social distance policy. In small groups we were lectured about the dangers of coronavirus. This manager tried to intimidate everyone, claiming he had sacked 50 drivers in a single day because he was not happy with their efforts to maintain social distancing. He told us that we are all responsible for the spread of coronavirus. If we did not keep to the rules as vigilantly as we should, we would be endangering everyone inside and outside the workplace, causing the deaths of families and vulnerable people. He also reminded us, in choice words, that being sacked at this time could “ruin your life”. The reality of working life was presented so callously, having to listen to our own experiences during the pandemic arranged, repackaged, and presented as patronising and threatening lessons – this was emblematic of Amazon’s approach to its workers. This manager proceeded to ask all of us to personally report any single instance of a slight violation of social distancing rules, turning workers into informers. Many workers would thereafter lose their jobs – a result, not of deliberate breaches of social distancing protocol, but of the incidental nature of mass work in a large and crowded warehouse. Workers were, in essence, punished for being workers.

Indeed, Amazon directly endangered workers on a daily basis. The necessity of work on the floor at Amazon seemingly required breaking social distancing rules, and this was intimately understood by workers. Amazon offers services like same-day delivery and commands a huge share of the market. To meet demand and fulfil its orders and responsibilities, the company has to work fast. In practice, this means workers crammed into overcrowded aisles, forced to lift heavier and greater numbers of parcels alone, and pressured to work in close proximity. This process was exacerbated by Amazon’s constant hiring of surplus agency workers. One week, a mass of new workers arrived from another Amazon warehouse to help with excess orders. At the time, there were reports in the media of Covid-19 outbreaks at other warehouses.

Workers would be assigned picking areas within long, narrow aisles, situated between two conveyor belts. They would have to pick heavy bags and parcels, sometimes filling four large carts before being assigned another route. As more and more workers were assigned to pick in the same area, there were more and more “stagers” needed to come in and out of the aisles to replenish the supply of carts. As a result workers struggled to find space to move. Throughout this, managers would be screaming at you to maintain your social distance. The whole time, workers’ scanning devices time them and measure their picking rate. If you worked slowly, another manager would turn up to rush you, rarely sympathetic to the contradictions in upholding social-distancing. This chaos was extremely stressful, with contradictory orders barked at workers caught between two impossibilities. I found that these managers implicitly accepted that social distancing would have to be broken, but chose to scream at workers anyway to project all responsibility on to them. Often, workers would be forced to stand inside carts in the middle of the aisle while waiting to pick, as other workers would be pressured to move ahead and find their assigned section. Managers and “social-distance ambassadors” would yell at you here, telling you not to step in the carts, and would bark at you for stepping out as you would then be in proximity of other workers. Workers would shout in exacerbation and ask where to stand. “Don’t talk back to me” was the typical response of those responsible for ensuring safety, even when asked by workers where it was safe to move.

The majority of the workforce were put in danger, caught between risking their health and losing their job. It is clear that, while an unsurprising feature of work at Amazon, this kind of turmoil is a general contradiction of capitalism. In the absence of unions or workers’ power, the injuries and risks sustained by workers are not simply accidental, but accompanying features of a labour process driven solely by profit. At Amazon, unions are categorically rejected. Amazon claims they do not represent the interests of workers. Yet, in the past few years, there have been hundreds of ambulances called-out to UK Amazon warehouses. There have been instances of workers left injured for life and even a report of a worker experiencing a miscarriage at work and being sent home on a bus.1

With the coronavirus pandemic, Amazon has continued this well-documented track record of endangering workers. In the US, Covid-19 cases amongst Amazon workers in winter were in the tens of thousands. In the area I worked, Covid-19 cases regularly exceeded the national average. Workers I knew caught Covid from their children, and reported feeling unwell weeks later at work. Amazon also brought in workers from another warehouse in a different part of the country to help bolster work. Not only did they fail to uphold health and safety policies, but Amazon consistently weaponised these very policies as their excuses for firing people they themselves put in danger. Servicing customers - with whom Amazon are “obsessed” - at the rate market competition demands, means putting workers’ lives in danger. Until workers’ rights are prioritised above “same-day delivery”, this will clearly continue. Labour politicians often condemn Amazon, telling the company to “step up” – but this implies Amazon has a conscience, that it is capable of humanity. If they really care about labour, they should start addressing workers, as change can only be brought about and enforced by workers themselves.

Even Commodities Grimace

The warehouse would regularly struggle to meet demand in the lead up to Christmas. Drivers would be held up waiting for parcels to be staged for loading, and would sometimes beep their horns in protest. In these moments, some managers would chip in, helping to pick and stage parcels. One particular day, after being assigned to an overcrowded area of the workplace (impossible to socially distance within, of course), I reported this and was bluntly told: “you have to do it.” Working as fast as I could, I was continually hassled and reprimanded by a particular manager, who, concerned there might be a slight delay in delivery times, decided to pick alongside me. They continually passed me with no consideration for social distancing. I could tell they were sweating under pressure, perhaps fearful of their own bosses, and I actually sympathised. Yet they threw boxes at me, pointing and shouting. “Down!”, they yelled, smacking their hands against the boxes when I didn’t pack fast enough. I lost it at this manager, told them they had no right to speak to a person like this, and asked for their name which they refused to give me. Other managers I argued with also refused to tell me. I was later pulled aside, reported for asking a manager’s name! I was told the manager “was trying to help me”. They were trying to induce me to feel guilty for having an issue with being put in danger, insulted, and spoken to like an animal.

It was strange to see the little smiling boxes – Amazon objectified – kicked, booted, and thrown around the place in moments of chaos like this. In Amazon’s advertisements, the universal commodity is endowed with a little magic, an ethereal twinkle behind the cheeky trademark-smile. In one of their TV ads, you follow the journey of a box that’s carefully passed along conveyor lines, dropped into bags, nestled in vans, and finally opened at the end by a delighted little girl. She is the only person we see, the only human expression – a happy customer, her joy anticipated by the box’s smile (yes, it too feels joy, it loves serving customers!). Perhaps there is the odd worker’s arm caught in the shot, an inconvenient delivery driver, but the workforce is overall absent from the advert – necessary to conceal the inner-workings of logistics! Because in the warehouse, workers are considered unworthy of protection, while little parcels are fawned over like gods. However, I am sorry to report that even the precious boxes have a horrid time in peak seasons. They too suffer through Amazon’s race to sell! They are booted by steel-toes; crushed inside carts and under boots; their contents smashed from overfull bags and carts. When they are not dodging kicks and balancing on carts, they even have to navigate over putrid bottles of urine. What a treacherous circus! In the warehouse, even the commodities do not always smile – they too are often upside down and grimacing!

Later that shift, some workers who witnessed the whole affair with the managers expressed solidarity with me. “Well done for giving it to them”, “they are fucking bastards!” I felt great joy when co-workers spoke with me like this and expressed a bit of solidarity. It was the only time you felt human in the place, when you stuck up for yourself, and when you felt the common frustrations and talked about them. This type of despotism exercised over workers was not uncommon. It was the norm. Sometimes you would snap, and rightly so. One worker told a manager to “fuck off” and was sacked on the spot. Another worker with the highest picking rate – the most productive worker in the warehouse – was sacked one day simply because a manager did not like his tone. When I heard about these sackings, I asked co-workers if we could do something together like demanding the re-hiring of these workers. But workers just shrugged their shoulders. Nobody had any positive experiences with managers, and it was considered too risky to do anything that might endanger your job.

Solidarity, Delusions, Fatalism

These kinds of daily injustices united workers against managers. Common grievances against their disdain and lack of respect served to bolster a connection amongst workers. The atomisation of the work meant we might not otherwise ever talk to one another. Often, workers would express contempt for the way the work was organised. Some thought that if we could just implement simple policies, secure simple rights at work, the place would function so much better. For others, every aspect of the work was ignoble and rejected. Just being inside the place was more like a prison than work.

Workers expressed desires to challenge these injustices in several ways. One worker told me, after being sent home before starting a scheduled shift, that she wanted to start a group. Some of us thought about starting a petition to present management over shift cancellations. Ultimately these ideas were rejected as too risky, but a feeling of enthusiasm was generated on the floor when discussing them. Some workers regretted that “we have nobody in here to represent us”, and others expressed a positive assessment of GMB’s drive to discuss Amazon’s poor working conditions in parliament. Workers agreed on the merits of union organising, but expressed harsh doubts as to whether it would be possible, owing to the overwhelming power of the company.

Some workers expressed a desire to rebel, not just against Amazon, but against a total system they felt oppressing them and thwarting their futures. Many of these expressions lapsed into fatalistic outlooks: “what’s the point, though, nothing will ever change.” Conspiracy theories were unfortunately common amongst young workers. Some speculated about the Covid lockdown and the conspiracy of a “new world order”. On three occasions, those expressing conspiracy theories concealed a disgusting anti-Semitism. It wouldn’t take long for condemnations of “the deep-state” to turn into “Jews control all the media.” I challenged workers who said these things, leading to uncomfortable arguments. It revealed a great dearth of political discourse and class consciousness amongst many young people. One worker I talked to even professed fascist politics. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this guy also admitted to being an arse-licker in an argument about bosses.

Hatred of Work

Many young workers rejected any positive identification with the job and with their labour. A great indignation at being in the place was common. This manifested itself in a number of ways: we would sit at every available opportunity, and if managers barked at us to stand, we would argue with them or do so only to sit again as soon as they walked away. We called “social-distance ambassadors” the “two-metre Nazis”. Walking with indignation was important, keeping your head held high was a form of rebellion. Skiving was common and became our main objective. When you worked, you were treated like shit anyway. I had some conversations about capitalism and the nature of exploitation inherent in the economic system. Despite a general lack of political convictions, almost every young worker I spoke to in Amazon intimately felt how it and other companies derive their profit and their power from the exploitation of workers.

After several months of the place, I decided to shirk work as much as possible. I walked around the warehouse talking with workers, having a laugh and ignoring all managers and their ugly, soul-crushing presence as much as possible. You are made to work like a beast in there, and receive nothing but pain for your efforts, so I skived like a trickster instead, abusing every possible gap in the system. With so many new workers starting, with the density of the work and multitude of tasks, you could, with a bit of skill and caution, manage to slip away, to become invisible for a while and find some breathing space. Many of us did this, our way of reclaiming time and value. Of course, it was impossible to entirely escape the tension of the warehouse regime short of quitting. One day, I couldn’t take any more of the constant bullshit and puffed-up orders. Arguing with a particularly hated manager, I told them what I really thought of them and the contradictory orders they upheld. I wasn’t able to appeal Amazon’s decision to sack me, neither was I given the chance to see HR.

Since leaving, I hear Amazon promote how great and generous and benevolent they are, giving “all” workers bonuses during the pandemic. I do not think I know a single agency worker who ever got a bonus before Christmas, and many have still not been paid properly. An increase of 20 pence in hourly pay (from £9.50 to £9.70) was the only pre-Christmas ‘bonus’ we received - and this hardly counts for much when shifts are frequently cancelled. I hear reports in the media of Amazon stealing tens of millions of dollars from their drivers in the US, how in Scotland their warehouses have been publicly funded by the taxpayer, and yet they evade paying tax. I think of the “hard-earned” wealth of capitalists, and of the workers who have not even been paid correctly. How can anyone look at Amazon’s media statements, their values, their propaganda and lies, and buy into any of this for a second?

As I emphasised above, to be a worker according to Amazon’s criteria meant to be in a position of powerlessness toward your job and the company. To be an Amazon worker was to be simultaneously put in danger and held individually responsible, indeed punished, for the consequences of being put in danger – and even accused of endangering others. Workers who bust their backs every day are made to feel worthless, and yet the commodities they package and sort are treated like sacred idols – when they are not thrown around from excessive demand. The weight of this kind of environment was psychologically unbearable. Due to the nature of the work, conducted on a dense scale, it was impossible to subscribe to social-distancing formulas alongside managers’ insistence of speed. To be a worker meant to be punished for being a worker, to occupy a position of complete negativity – a lose-lose situation where you were punished for working and punished for not working. It is only right in such environments that workers engaged in small acts of resistance. It is only right these go further!

Some Final Thoughts

These are just some of the things I witnessed at Amazon. Others have conducted inquiries into the place.2 For those interested, these are good starting points for wider discussions into the necessity for organising labour in the UK. I witnessed few acts of outspoken resistance to Amazon managers during my time there, but I did see, every day and every hour, a great disdain for the hypocrisy, the lies, the phony image, and the injustices committed against workers at Amazon. Before I left, I had some encouraging discussions about unionisation. The pervasive fatalism of “we can’t do anything, there’s no point, nothing will change”, while a reflection of a lack of power, also stems from questioning current power relations and, implicitly, rejecting them as unjust.

Ultimately, it is not just the hum of conveyor belts and the screams of despotic managers that echo inside Amazon centres: beneath the surface, these places pulse with working class hatred and subtle acts of resistance. Of course, some workers were taken in, won over to the ideology of the place. “It’s not a bad place to work, really”, an old worker around retirement age once said to me, “sometimes we get biscuits.” Biscuits. Not a secure job, a secure wage, safety at work or a modicum of respect, but biscuits. Let this speak to the reciprocity of capitalism, and to the lie of the “dignity” of labour at Amazon, free-enterprise’s glorified shithole!

Image credit: Eli Christman.

-

See reports from GMB and The Guardian. ↩

-

See Amazon Inquiry by John Holland. ↩

author

Enzo

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

A Season in “Hell”

by

Enzo

/

March 26, 2021