Amazon Inquiry

by

John Holland

October 7, 2020

Featured in From the Workplace (#13)

An inquiry at a distribution warehouse

inquiry

Amazon Inquiry

by

John Holland

/

Oct. 7, 2020

in

From the Workplace

(#13)

An inquiry at a distribution warehouse

I’m a worker at the Amazon Distribution Warehouse in Rugeley in the West Midlands. Amazon calls its warehouses ‘Fulfillment Centres’. The centre in Rugeley covers 700,000 square feet, has at least 1,500 staff, and distributes up to 600,000 items a day. Since the coronavirus pandemic hit the UK, Amazon has responded to a surge in demand by bringing on extra workers (mostly agency staff), whilst making a lot of changes to the way work is done to ostensibly comply with social distancing rules.

Division of labour

Work in the warehouse is divided into small repetitive tasks, with different teams of workers focusing on only one of them throughout the day. It’s highly organised, everyone functions as a mere cog in the machine, barely aware of what the other cogs are doing. By my understanding, there are five different types of worker at the warehouse, not including the various levels of management and support roles. These are:

- Receivers: These are the workers who spend their days unloading boxes from lorries as they arrive at the Fulfillment Centre, and sending them to be prepared, or ‘prepped’.

- Preppers: These are the workers who prepare the goods so that they are ready to be stored. This generally involves opening each box, attaching an Amazon specific barcode to each item, and then putting them back in their boxes and sealing them again. Some items need to be placed in specific bags. The boxes are then sent for stowing in the four floors of thousands of storage aisles that make up most of the building.

- Stowers: These are the workers who store the goods once they have been prepared. Each stower is assigned to a specific location within the building close to a lift, where carts of goods will constantly come up and be pulled out for the stowers to take away and store in the aisles. Each stower has a scanning device which records their work. Their job is to take a cart and scan each item by its barcode, store it in a bin in the aisles, and then scan that bin’s unique barcode to record it. This process is repeated until the cart is empty, at which point another cart is ready to be sorted.

- Pickers: When orders are made, the items are collected from the bins by a team of workers called ‘pickers’, who walk up and down the aisles with their own carts, each holding a scanner giving them instructions about which items to pick and where to find them. They then scan the item, as well as the bin they took it from, to log on the system that it has been removed. When their cart is full they take their items to the deliverers

- Deliverers: Lastly, these are the workers who go through the items picked from the bins and sort them into specific individual orders and pack them so they are organised by geographic location for more efficient delivery, after which the items are packed into lorries and taken away for delivery.

These groups have almost zero contact with each other. In fact, the way work is organised means you can quite easily go all day without ever having a conversation with a coworker. If you were to construct a work system primarily to prevent workers organising, you wouldn’t be far off this. Since working at the warehouse, I have mostly worked as a Stower but have occasionally been moved to work as a Prepper on some days. Amazon must have a system to calculate what proportion of their workers they need on each team for any one day to ensure the wheels keep moving efficiently and so no team is ever kept waiting by another earlier in the process. Whilst working in the Prepping area, I’ve also been asked to help out with moving pallets of goods that need to go into a specific section from one area of the warehouse to another. I’ve been repeatedly told that I will receive training on how to do this and it will happen very soon, but for now me merely saying that I know how to drive a pallet truck was good enough. I don’t actually have any certificates, I just remember how to do it from copying someone else at a previous job. They don’t even require us to wear steel toe-cap footwear working in this area, although I wear them voluntarily as I’ve already dropped a couple of boxes on my feet and would not like to try that in my trainers.

Maybe I’ll drop a pallet on myself next week and sue Amazon.

There are also staff who don’t fit into the categories I outlined above, whose role is to provide extra organisation for the workforce. Each team has a ‘Leader’, whose main role seems to be to provide motivational speeches at the beginning and end of each day and tell us to come speak to them if we have any problems. They are not well liked by the workforce. Speaking to them regarding any problems usually just results in condescendingly being told that there’s nothing that they can do about it and that we’re just making a fuss. Making fun of our Leader is probably the main way me and my co-workers keep ourselves entertained, and it does give us a sense of collective identity against the bosses, but this is mostly counter-acted by how everything seems constructed to prevent workers organising.

Another important group are the ‘Problem Solvers.’ These are workers who stand around behind ‘Computers on Wheels’ (called ‘Cows’ by Amazon) monitoring the work process for errors and correcting for them. For example, if you scan an item’s barcode and it comes up on your scanner as a different item, you need to hand it to a ‘Problem Solver’ as clearly something in the process has gone wrong. A common error is that items which are supposed to be restricted to a specific section are mixed in with others. For instance, Pet Food and Poisonous Substances must be stored in their own specific sections, lest Amazon unwittingly kill someone’s dog. Much of this work feels like it would be quite easy to automate. In fact, the constant going back and forth to ‘Problem Solvers’ feels like we are Alpha Testing Amazon’s systems, so that all the errors in the system can be ironed out before the inevitable introduction of robot workers who will take all of our jobs. Despite essentially being managers, the Problem Solvers aren’t paid any more than we are. To get to a higher paid position you must get some managerial experience first, so workers essentially accept being promoted for no extra pay. All these layers of management undermine worker solidarity quite effectively. Really we’re in the same boat as the Problem Solvers, but the way work is organised makes us feel the opposite.

Working at Amazon

Something peculiar about working in Amazon is the strange language you have to pick up, which can be bewildering at first. I’ve already mentioned that warehouses are now ‘Fulfillment Centres’ and ‘Problem Solvers’ work on ‘Cows’. Well, workers are not called ‘staff’ or even ‘employees’ here. We are all called ‘associates.’ Whether we’re workers or bosses, we’re all supposed to be the same, and our relationship with the corporation is made to feel all cuddly, though really it’s just made more distant. The workers are aware of the implications of this. One staff member talked to me about a ‘propaganda video’ (their wording) Amazon uses to teach their management how to identify and prevent union organising among their ‘associates’. This can be found on YouTube for a taste of how these people talk.1

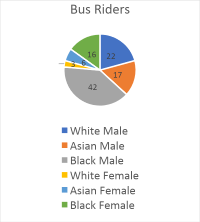

I live in Birmingham, around 35 miles from the Fulfillment Centre in Rugeley. Since I don’t own a car, my only way of getting to the Centre on time for my 7:30am shift is with the buses Amazon puts on, which leave Birmingham City Centre at 5:50am or 6:10am. They charge us £4 to be driven straight to work, and £4 again for the journey back. I’ve been told that the service used to be free, but Amazon has since realised they can charge workers for it and they still come - so why not. I have been keeping count and the workers who get the buses are mostly male (as is the workforce in general) and overwhelmingly non-white, a lot more so than the workforce once you arrive. I assume the white workers are more likely to have cars or live nearby. I should note however that although ‘White’, the majority of these workers are not British. Most seem to be Romanian or Polish. I leave my house to cycle to the City Centre at 5:30am, catch the bus at 6:10am to start work at 7:30am. My shift ends at 6pm and then another bus leaves for Birmingham at 6:30pm, arriving around 7:20pm, and then I cycle back home, arriving around 8pm. Including travel time it’s a 14.5 hour work day, four days a week.

There are two different kinds of workers, those of us who are employed by Amazon, called ‘blue badges’, and those who work for an agency, who are called ‘green badges’. We have to wear these coloured badges with our personal details on lanyards all day, so we’re easily identifiable. Those of us who work for an agency and have been brought in during the pandemic to help meet increased demand are designated as ‘heroes’. This reminds me of how the government is calling NHS workers heroes for being so brave working against the coronavirus without adequate PPE. At Amazon, it’s another strange use of language that they take even further, as each agency staff member is literally given a badge with a Superhero on it (e.g. Hyperion, Drax The Destroyer, and so on - I’m not good with superhero names). They are then told to check the Heroes Board every morning to see which section of the building they have been assigned to work at for the day. We generally work in a different place every day, so we never really get to know anyone, which makes organising very difficult. I find calling workers ‘superheroes’ incredibly patronising, although my co-workers find it more funny than anything else.

From my conversations with migrant workers, I understand that many of them live together in shared accommodation in and around Rugeley. Generally, one of them has a car and drives the rest to work each day. The pay is £9.50 an hour, with 1.5x pay for one day of overtime a week and 2x pay for the 2nd. The British workers mostly seem to be people who are on furlough or have been laid off since the coronavirus pandemic started. One co-worker told me he doesn’t believe that his job will actually be there when the furlough scheme ends, so even though he’s getting enough money from that he wants to secure new employment before losing his old job. Another says the 80% pay they’re on isn’t enough to cover their expenses so they needed to find work. I must say there seems to be virtually no tension between the migrant and British-born workers, which has not been the case in many of my previous workplaces. They share a common contempt for Amazon management and the frustrating rules imposed on us all.

Rules of the work

Ah, the rules. They are rarely fully explained to you, you just find out about them whenever you’re either caught breaking them, or a co-worker explains them to you to try to keep you out of trouble. For instance, there are a set of rules about the speed of your work. For stowers, you must stow at least 1 item every three, four, five minutes (the precise time changes regularly), or you will be logged as ‘idling’ and are liable to have your pay docked for ‘idle time’. You must also meet a quota of items stowed. I’m told that there’s a room somewhere in the building where someone is constantly monitoring everyone’s work speed, and can send someone out to find us if they notice someone is idling a lot. At the moment, I’m told you must stow an equivalent of 35 large items or 178 small items per hour, or you will be classed as idling unless you can give a valid excuse. Running out of work due to delays earlier in the process is a valid excuse. Going to the toilet is not. We do get told that we’re allowed to have toilet breaks, which is technically correct (the best kind of correct), but in reality there’s no way you can get to the toilet and back in time to prevent being flashed as idling - unless you’re lucky enough to be working right next to one. By my count there are 4 different toilet facilities open to workers located around the 700,000 square feet building, all on the ground floor, so good luck with that one.

We have two 35-minute breaks in our shifts. The rule is that you must be working each minute on either side of it, which can be monitored by your scanner. So, for instance, if you go on a break at 12pm, you must make a scan at 12:00pm and another at 12:35pm, or you will be classed as overstaying your lunch break and are liable to have pay deducted. Of course this means the breaks aren’t really as long as advertised, as the time it takes to walk from your workplace to any one of the five canteens scattered around the huge building can be anything up to 10 minutes, especially with 2 metre social distancing rules being enforced - meaning you can only walk as quickly as the slowest person in the corridor. In reality my break time is more like 20 minutes before I have to walk back to my shift area so I can be on time to make another scan the minute I’m back.

For this reason, I rarely bother buying food at the canteen, as the extra time it takes queuing up means you barely have time to finish before you need to start walking back. You are allowed to bring in packed lunch or other items into the building, provided you use a clear plastic carrier bag that Amazon provides you with. It’s never been explained why exactly this is necessary. I’d normally guess it’s to ensure we don’t bring weapons into the building or something, except the rules have got far stricter with the pandemic so that doesn’t make sense. It feels like going in and out of prison.

Another rule you will soon learn is that you must be on your feet the entire shift, as sitting down encourages idling. This gets very frustrating when you have to stow lots of small items in the bins located at the very bottom of the aisles, as you’re instructed to bob down on your feet or on one knee to do the job but nothing more than that. I also saw one worker get a stern telling off for having a sit down on the stairs while waiting for work to arrive. We’d been waiting on our feet for around 20 minutes. One of the jobs of the ‘Leaders’ seems to be patrolling the corridors to scold any workers they find breaking the rules. I have overheard some of my black co-workers complaining that they feel racially profiled by these patrolling disciplinarians, and that they get the same feeling as being the black kid suspiciously watched in a corner shop for no reason, while the white kids run around as they please. One black worker told me on the bus back that they had been aggressively threatened with the sack for having their mask below their nose whilst working on the top floor where it’s really hot, when they were certainly not the only one who’d been doing that. The heat and amount of walking you have to do here can get quite tiring. I’ve used a step counter app this last week, and I’m averaging 7.1 miles of walking a day during my shifts.

As well as the Leaders constantly walking around keeping an eye on you, something you can’t help notice working in this place is the CCTV. There are cameras absolutely everywhere, I don’t think there’s a single spot in the building where you aren’t under surveillance by at least one CCTV camera. I feel this has a profound psychological effect on all of us, the awareness that we are constantly being watched. I had one worker advise me to never ever put an item in my pocket, even if I just wanted to carry something and my hands were full, as it could be interpreted as an attempt to steal.

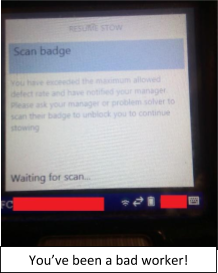

Another thing you need to be careful of is making any errors in the storage process, mostly doing something in the wrong order or attempting to stow something in the wrong place. For instance if an item you scan comes up as ‘Flammable’ you should know it has to be stowed in Flammable Land (more on that place below) and thus must be taken to a Problem Solver if you’re not already there. An attempt to stow it anywhere else can result in a message on your scanner telling you you’ve made one mistake too many and that you need to go report to your manager to explain yourself before you can start working again. Quite disconcerting! It all adds to the feeling of being constantly monitored. Not as disconcerting as the noisy conveyor belt you hear all throughout the stowing aisles though, which makes this constant ‘dah dah dah…’ sound at almost the exact same pitch and tempo as the opening guitar riff of ‘Take Me Out’ by Franz Ferdinand so you’re constantly anticipating the words SO IF YOU’RE LONELY… to burst out from the PA System before you remember that it’s just the conveyor motor.

Or maybe that’s just me.

An example of worker solidarity and resistance in this place is how workers are constantly coming up with tactics to get around the monitoring and game the system so they can bend the rules but not get flagged up on the system. For example, if you want to go to the toilet without being flagged for idling, a good get-around is to carry a few small items with you (e.g. a lipstick) and just scan and stow one every few minutes as you’re walking down the aisles, so the system never picks up on you being away from work for very long. I don’t mind describing that one as I’m sure management have worked out that people do this already, but that’s just to give you an idea of the tricks workers come up with to keep the automated monitoring off their backs.

Flammable Land

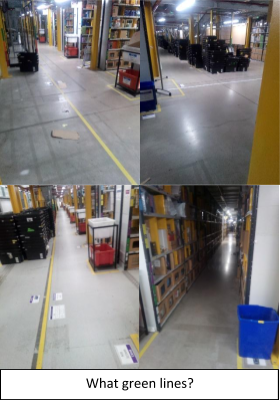

Another interesting feature of this workplace is the fire safety routines. All my co-workers agree that during our initial training period, we were told repeatedly that if a fire alarm was to go off, we must all immediately drop whatever we are doing and follow the green lines on the floor, which would lead us to the nearest fire exit. Sounds sensible enough. Then one day I thought about it and looked at the ground, and then suddenly it hit me.

What green lines?

I must have spent 10-15 minutes one morning trying to find where these green lines were. There’s plenty of yellow, white and grey lines all over the place but no green ones. This is not a very useful fire safety procedure. I guess if a fire alarm goes off I’ll just follow everyone else and hope for the best. Your chances in a fire seem very much dependent on where you’re working anyway.

As I mentioned earlier, although most goods can be stored anywhere, there are a few specific sections in the building for storing goods that must be kept separate from everything else. One of these sections is called ‘Flammable Land’, which sounds like some kind of theme park for pyromaniacs. There is a constant theme of making out that working here is enjoyable. The Team Leaders even seem to be told to shoehorn in the phrase “have fun!” in their speeches to us. But anyway, Flammable Land consists of aisle after aisle of flammable substances, not in the sense of “will burn” like paper, but things that will burn very quickly like petrol, certain perfumes etc. The idea is, if there ever was to be a fire in the building, it wouldn’t spread very quickly because all of the things that would easily go up in flames are all kept separate, so we’d have plenty of time to evacuate the building. Now, what exactly is supposed to happen if the fire starts in Flammable Land has never been explained to me. I guess if you’re working in there and hear the fire alarm, just run like hell following the green lines which aren’t there before a raging chemical inferno engulfs you.

Because of the pandemic, there has been yet another group of rule enforcers created. These are called the ‘Social Distancing Champions’, whose job is to patrol the site looking for any workers who are within 2 metres of one another and tell them to step away. The vast majority of workers seem to already be trying quite hard to stick to the social distancing rules, so this hasn’t caused many issues that I can see. Although the role of Social Distancing Champion seems to have attracted some people who are more interested in telling others what to do rather than in health and safety. I did tell my manager about the social distancing disaster that is the Heroes Board. Every morning I see loads of agency workers all coming in at once to look where their shifts are, at which point social distancing collapses as they don’t feel they can wait long enough to all look at it one at a time for fear of being flagged as idling. It’s quite clear that enforcing social distancing would be made a lot easier if Amazon would just relax its ‘idling’ and ‘quotas’ rules so workers don’t feel that they have to constantly rush around pushing past each other to not get caught out. But that would hurt profits. The only real step they’ve taken is moving the time the bus leaves from 6:10pm to 6:30pm, so workers now have an extra 20 minutes to get the bus after finishing their shift so there isn’t a huge rush for the doors all at once. But I guess that’s a change that doesn’t negatively impact Amazon in any way, it just means workers get home 20 minutes later.

I witnessed the social distancing regime truly break down when we had our first real fire alarm since the pandemic. Firstly, after the alarm went off I had to explain to several Romanian workers who I’d found continuing on, that they had to leave the building. They didn’t seem to realise that this one wasn’t a test, although it’d been explained to us that the tests were at 12pm Wednesday and Saturday, so this must have been a real fire. Several hundred workers all dropped tools and followed invisible green lines leading them out of the building into the car park, where they were all clumped together and told to wear strange tin foil overcoats that made us all look like the Cybermen out of Doctor Who. I’m not sure what the point of that was. Maybe it was to keep us dry in case it rained? At least we got a bit of excitement. But the true highlight of the fire alarm was finally discovering these legendary green lines. There’s two of them. They’re around 6ft long extending immediately in front of the fire exit door, so totally useless as a guide unless you happen to be standing right next to it, by which point it’s pretty obvious where the fire exit is anyway. The mind boggles at why they spent so much time training us about these fire exit green lines.

Building solidarity

It’s very difficult to establish bonds with other workers here. You’re constantly being moved around from section to section working with different groups each time, and everyone is working a variety of shift days and break times. If you were to set up a work regime primarily with the goal of hindering union organising, this is exactly how you’d do it. On top of all that, there is a big turnover in staff. Workers leave regularly because they can’t put up with the working conditions long term, especially the new workers who’ve come in during the pandemic. Amazon never seems to stop hiring new people, so they’re obviously replacing others. I suspect they periodically just sack workers for not meeting targets enough so they can be replaced with newcomers, and thus constantly increase their efficiency averages.

I was warned one day that my stowing speed had dropped to less than 50% of the average of everyone else that morning and was told to explain myself, but it was more bad luck (for example, lack of shelf space slowing me down) than me working slow so this wasn’t repeated. Someone told me on the bus going home that a lad had turned up to work that morning at 7am only for his entry ID not to work when he tried to scan in, and was then told it didn’t work because he’d been released. Must not have seen the email.

Yes ‘released’ is another Amazon Language word, nobody is ever sacked here. I first heard that word when I was late one day and off sick for a day not long after, and was told that if I had another sick day I would be released. Not sure what the timeframe of that was, surely not forever, but I haven’t been off sick again to find out. This does seem to undermine their strict anti-covid stance though, when they’re essentially incentivising workers to come in sick or else risk being sacked for poor attendance.

Still, I do think there are ways union organising could succeed here with a lot of effort put into new strategies. I’ve also overheard another coworker at lunch telling people that he’d got his union involved (as an individual, no unions are recognised) after having to explain absences in a disciplinary meeting, when he’d already told management that he’d had a death in the family. One issue is a lot of the workers are Romanian, and they’re mostly cut off from the native workers. I don’t see a unionisation effort succeeding unless the union is willing to invest in a Romanian-speaking organiser. Also talking to workers directly outside the premises (as I understand GMB have attempted) is probably a bad idea. Workers are still nervous about being monitored. Some form of online outreach is probably necessary, but if we need physical interaction it’d probably be smarter to go to the bus drop off points in Birmingham, Wolverhampton, Walsall, and so on and speak to workers there where there are no Amazon managers snooping around.

It doesn’t take much imagination to realise how very poorly paid we are for the amount of value we’re generating for Amazon. At the time of writing Jeff Bezos has a net worth of $189 billion. If this place stopped functioning it’d probably hit the whole economy of the West Midlands with how dependent people and businesses are on online deliveries in these times. How many other workplaces can say that? Higher pay really should be an obvious thing to organise for, although I don’t hear many workers actually complaining about that, we’re still all paid slightly above the living wage and many people’s expectations are low enough to consider that acceptable. The biggest thing people are unhappy with is the complete lack of control they have to decide anything in their workplace - the excessive surveillance, arbitrary rules, aggressive management methods, and so on. Aiming to get management off our backs and just make this a more pleasant place to work would probably be more galvanising.

Featured in From the Workplace (#13)

author

John Holland

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Introduction: Why Worker Writing Matters

by

Notes from Below

/

Oct. 7, 2020