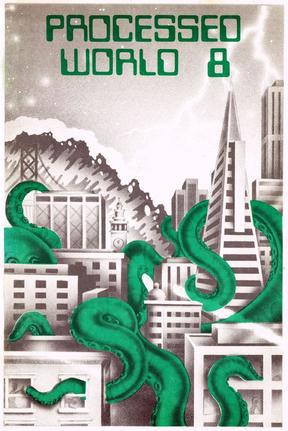

Processed World

We didn’t know it at the time. The revolution we thought was on the horizon was not going to overthrow capitalism or usher in an era of solidarity and mutual aid. On the contrary, the word “revolution” in the mid-to-late 1970s held a much darker potential. By the time Reagan got elected in 1980, the process of reasserting the power of capital over a recalcitrant and rebellious American working class was well underway. The “revolution” we would experience in the 1980s produced a massive U-turn, a return to the savage dog-eat-dog, everybody-for-herself, go-go capitalism that first emerged in the late nineteenth century. With several decades of hindsight, we can see now that we were at the dawn of the neoliberal city in those bleak days that for some of us felt so full of potential.

—Chris Carlsson, “When Punk Mattered: At the Dawn of the Neoliberal City” (Boom California, Sept. 8, 2015)

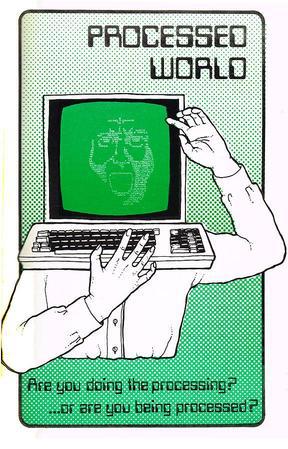

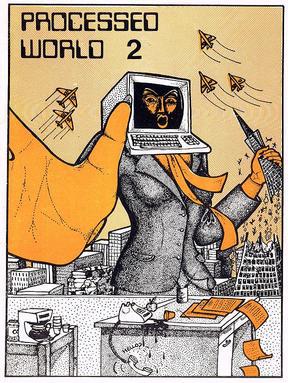

Processed World emerged from a much larger and strongly politicized culture that flourished in San Francisco 40 years ago during that mostly forgotten period between the “long sixties” and full-blown neoliberalism. Radical politics were percolating in many forms and places alongside the punk music scene. Copying machines were newly accessible at work, at school, and in shops where friends worked and allowed a great deal of late-night free copying. Many people began putting their collages, screeds, and cartoons on the poles and walls of San Francisco. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, the antinuclear Abalone Alliance was mobilizing thousands to block the local utility’s plans to build a nuclear power plant on the coast at Diablo Canyon; Nicaraguan revolutionaries and Iranian students crisscrossed the Bay Area urging support for the unfolding revolutions against US-sponsored dictators in their respective countries; tenants were organizing for rent control in the wake of the violent eviction of the I-Hotel in 1977; and strikes at local oil refineries, trucking operations, insurance offices, and restaurant chains dovetailed with a national coal miners’ strike.

President Jimmy Carter proved to be the initiator of the neoliberal turn towards privatization and deregulation that would take power more thoroughly in the Reagan/Thatcher years to come. The AFL-CIO was doddering along under the new but predictably stodgy leadership of Lane Kirkland who took over in 1979 from the ancient George Meany (the ultimate anti-communist Cold War hawk who led the AFL-CIO from its 1955 merger until 1979). The dramatic deindustrialization of the old Rust Belt United States was echoed in San Francisco’s own deindustrialization that followed the rise of containerization and the move of shipping across the Bay to Oakland. Blue-collar shipbuilding and repair were decimated, manufacturing had decamped for suburbs in the east and north bays decades earlier, and many neighborhoods in San Francisco were bleak, abandoned shells of the former selves (notably, the Haight-Ashbury, the Fillmore, and the South of Market).

San Francisco had recently been rocked by the twin traumas of the Jonestown suicide-massacre and the murder of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk in City Hall. A new youth revolt was in full swing with punk rock percolating through the underground venues of the City. Brash and radically left-wing, those “epic sounds of revolt, the declarations of refusal, the hilarious ridiculing of the powerful and rich, the pointed satire of the emerging technosphere, turned out to be more of a last anguished demand to seize the moment between the lost utopias of the 1960s and early 1970s and the capitalist triumphalism that dominated the rest of the century” (Boom California, Sept. 8, 2015).

Gays and lesbians defeated a statewide initiative in late 1978 designed to ban them from teaching in public schools, and the feminist and gay movements were fully identified with a larger progressive thrust. Gentrification was only just beginning, and the harsh displacement it would wreak was starting to impact San Francisco’s shrinking black community. African Americans were still over 10% of the city’s population, even after a decade of Redevelopment had decimated their homes in the Fillmore District, but were steadily leaving in the wake of the city’s rising rents and falling blue-collar employment opportunities.

I was 23 in 1980 and after getting myself fired from an information desk job at a local community college (for a subversive leaflet I had surreptitiously placed in all the fall schedules) I went off to a summer of R&R in New England. Alongside a swimming pool on a hot, muggy day, a thunder bolt struck. Let’s start a magazine called The Processed World… for people like us!” I blurted to Caitlin Manning, my romantic partner at the time. We had both been temping in financial district offices, and had already produced an agitational flyer called “Innervoice #1” describing the “rebellion behind the typewriter” that we were sure we would be taking part in. We had some of the requisite skills, equipment, and absurd amounts of self-confidence (like most 23-year-olds), so it didn’t seem far-fetched that we would embark on launching a new magazine (though we knew we couldn’t do it alone either—we joined quickly with Adam Cornford and Chris Winks to assemble the first issue, ably printed by our close friend Steve Stallone), though to be honest we didn’t really expect it to come out more than once or maybe a couple of times.

Revolution at the point of circulation

We were imbued with Marxist ideas about the working class, and found ourselves as wage-slaves in the modern office. Rejecting the typical politics of the era that focused on downtrodden folks far away, usually couched in sacrificial language, we embraced our own predicament and thought nothing would better address it than a blistering sense of humor and no-holds-barred analysis. Gathering some key friends to help with editorial, graphics, and printing, we labored over the first issue while the presidential campaign of 1980 plodded along.

Certain that Carter would win re-election and that there was no chance the doddering ultra-conservative Ronald Reagan could possibly triumph, we imagined Carter’s anti-labor privatization efforts carrying on until in 1984 he would be replaced by a social-democrat of vaguely leftish persuasion. We would be the perpetual thorn in the side of the sell-out and moribund labor movement, as well as the absurd Leninist left and the impotent politicos of the soft left. At least that’s what we thought during the long autumn of 1980. Then Reagan, improbably, defeated Jimmy Carter.

Our first issue came out in April 1981, with feature articles on the Blue Shield strike in northern California, and a survey of “New Information Technology” that tried to explore the ambiguous possibilities inherent in it. We saw ourselves as serious subversives, dedicated to fomenting revolution at the point of circulation, not production. By 1981 we could see that the deindustrialization process was leading to the much-touted service economy, but what were these so-called “services”? Mostly, as far as we could tell from our vantage points as temp workers in banks, accounting firms, real estate offices, and brokerages, it consisted of shuffling information—typing, mailing, filing, sorting, distributing, copying, and doing it all with then new-fangled skills like word processing on computers.

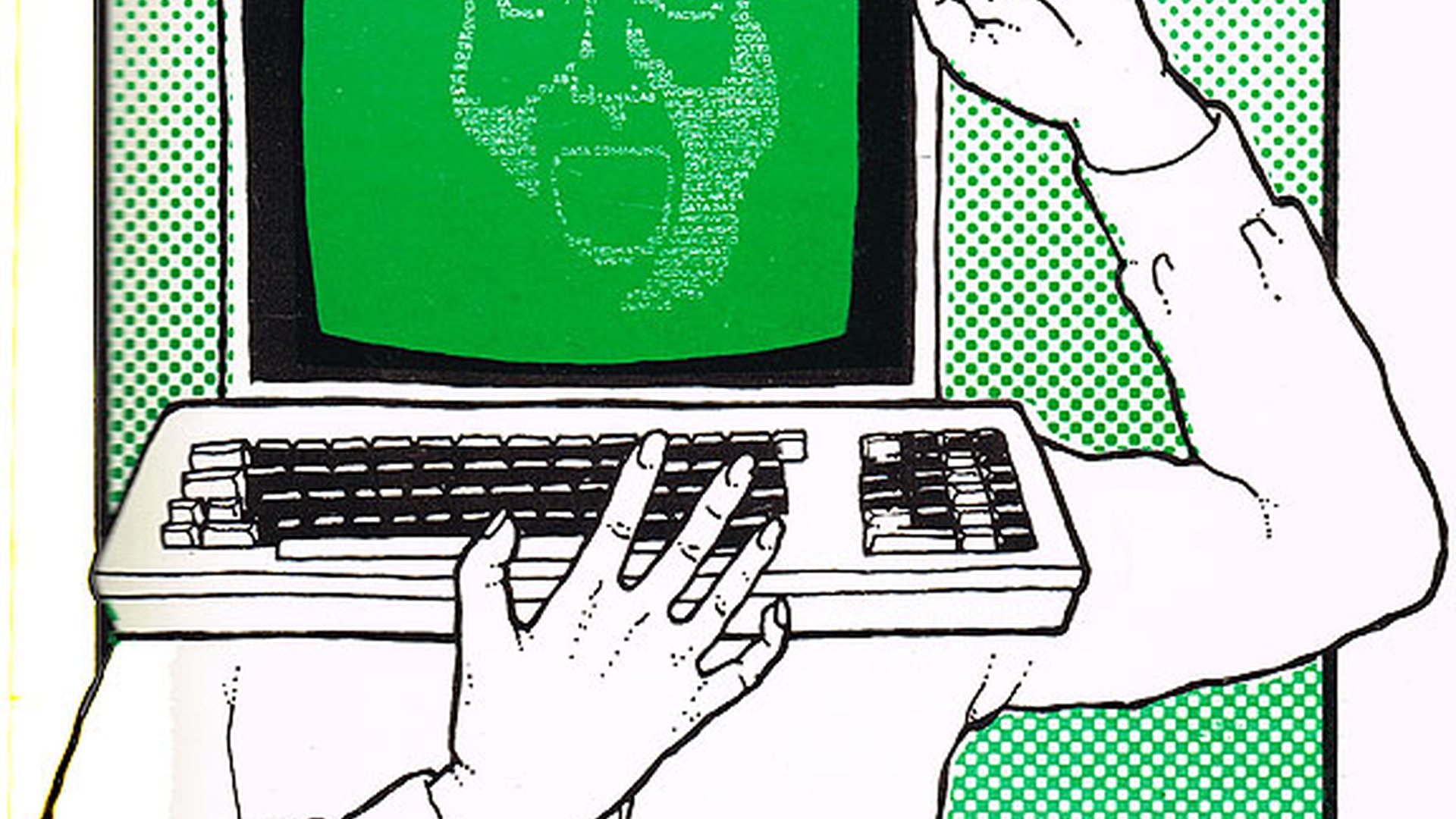

We spent our days in front of green or amber monitors, worrying about radiation exposure from the electrons pouring through our Video Display Terminals into our faces. After the first issue came out, we were deluged with letters to the editor and new volunteers. We had struck a chord. But beyond being dissident office workers in favor of overthrowing wage-labor, what were we going to do? We kept writing about our situations, and invited “tales of toil” from our readers, which poured in as both letters and articles, and filled our pages for the rest of the 1980s.

One of Reagan’s first acts as president was the mass firing of the Professional Air Traffic Control Officers (PATCO) after they struck early in his term (echoed during the January 2019 government shut-down when air traffic controllers and TSA workers stopped showing up at some east coast airports and forced Trump to re-open the government). This set the tone and was soon followed by aggressive attacks on unions in all parts of the country and the economy. Meanwhile, we saw close friends in the anti-nuclear movement grow terrified at what they saw as imminent nuclear war after Reagan belligerently ratcheted up Cold War rhetoric and radically expanded military spending.

By 1982 the Nuclear Freeze campaign had taken up a great deal of the political oxygen in the proverbial room. The anti-Sandinista war of Reagan’s CIA and NSA hacks was by then well underway, along with genocide in Guatemala and death squads in El Salvador. In the Bay Area, the Central American solidarity movement was growing rapidly; a burgeoning anti-apartheid movement was also beginning to find its legs.

Processed World shared opposition to U.S. militarism and interventions on behalf of oligarchs and right-wingers, but it was far from our focus. We kept our attention directed to our own daily lives, certain that the most radical challenge we could mount to the U.S. empire would be from within—especially, in our minds, from within the bowels of the circulatory system of modern capital.

Processed World burst on to the scene as the automated office was just starting to be implemented. This restructuring of decades-old white-collar labor processes required a surge of temporary employees while new computing technologies were being adopted. As temp workers in downtown San Francisco we found ourselves in the midst of this unannounced transformation. The human-machine interface, already over a century old, was undergoing yet another dramatic change and we were living the daily reality of it.

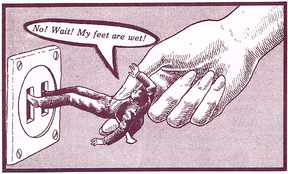

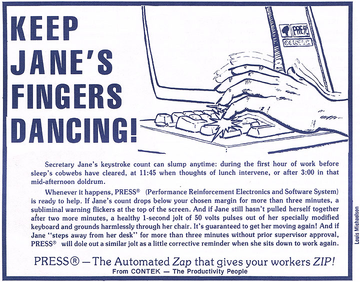

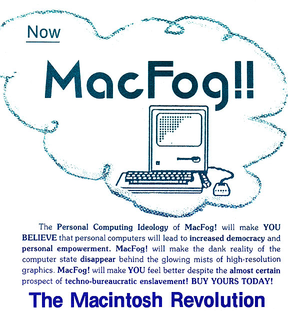

Hilariously, the business press at the time, primarily Business Week, was also trying to come to grips with the changes underway. They employed talented illustrators who week after week produced remarkable images that captured the confusion and fear that sudden automation of age-old processes was bringing with it. We’d discover these with glee on our boss’s desks, or in waiting rooms, and with a quick snip we’d collect the graphics for purposes of as the French called it, détournement. Pioneered by the Situationists in the late 1960s, the adding of words to images to uncover their “true meaning” was a tried-and-true technique and we had a field day. Whether the images portrayed weird cyborg humans or even stranger human-machine interaction, all efforts to soften the harsh new world were easily lanced by our satirical sensibilities.

In the pages of the magazine we gave ample coverage to nascent attempts to thwart business operations; notoriously we highlighted sabotage as a technique worth discussing. Ubiquitous sabotage is probably the norm for most businesses, and we published many “jokes” about how to scratch diskettes, put an “out of order” sign on a functioning copying machine, misspellings and typos as acts of disinformation, and even more direct forms of active disinformation when it was appropriate. An inability to guarantee accuracy by data entry clerks was certainly one of the major motivations for increased computer surveillance, much promoted by the business press in the early 1980s.

Looking back in Issue 14 in 1985, I wrote, “What emerged [since issue 5 in 1982] were accounts of individual actions for emotional and psychic survival in the office. One part of this is anti-management agitation, another part is sabotage. This reflects our experience that most people are not involved in collective responses to the modern office. But it felt different when the magazine started [in 1980-81].” With the defeat of the Blue Shield strike in 1981, and the national destruction of PATCO, and a rapid retreat from confrontation by organized labor during the withering recession of the early 1980s, we realized that an expansion of office worker organizing was not about to happen. And our own experience in various offices across San Francisco’s financial district showed us how difficult it was to find allies, and how difficult it was to even imagine organizing or collective action. We rarely stayed anywhere beyond a few weeks or months, and the people who shared our “bad attitude” that we did find, were generally equally unmoored from any given workplace or career path.

In retrospect years later, the infamous “bad attitude” that even became the title of our 1990 anthology was itself a curious concept around which to revolve. Sheepishly, old correspondents and friends who I had lost touch with over the years admitted when they finally reconnected that they were embarrassed to admit that they had “found a good job.” It proved unsustainable to keep working with a bad attitude towards the work, the employer, and one’s co-workers, and most of us, myself included, soon departed the office world for other ways to get money. Some became teachers, some self-employed in various capacities (I had a typesetting business), and others followed their artistic, writing, musical, or other talents into serious efforts to survive in those fields. A few remained as tech writers or programmers too, finding enough satisfaction with the technical challenges to justify remaining in the patently absurd and alienating environment of the modern office.

Our scathing irony, which seemed so edgy when we were doing it, later looked self-defeating to me. Building on the ironic tone struck by our favorite punk bands and unblinkered comedians and artists, we contributed our part to a culture that ridiculed sincerity. Ultimately, such ridicule helped delegitimize a great deal of honest political expression. Not to say that plenty didn’t deserve ridicule, but what we couldn’t know at the time was that our participation in this culture was making it ever more difficult for genuine expressions of sincerity to be made. After all, if you said something sincerely without an ironic twist you were obviously a benighted chump, someone who “didn’t get it,” and were naive at best.

Recognizing this in retrospect, it was nevertheless unavoidable that we took that tone at the time. The gushing enthusiasm for automation, new technology, and the endless efforts to establish a “positive attitude” as the sine qua non of good employee behavior drove us, and any thinking person, around the bend. The work was so easy and mind-numbing that almost anyone could learn a given job in a few hours or days at most, and thus the real test for employers was not your “skills” but your “attitude.” We came face to face with the growing dependence of many employers on the emotional labor that knit provider to consumer, worker to product, and employee to boss—and with our resilient “bad attitudes” we rejected it covertly or on occasion, blatantly. The overwhelming comment we received in our abundant mail was the relief that the writer “was not alone,” and that there were others who saw through the lies and propaganda with the same clarity they did. So we consistently attacked the business press, corporate propaganda, and the government throughout our years of publishing.

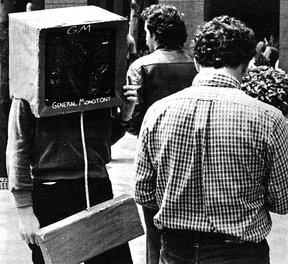

In issue 5 we offered an account of our intervention at the “Office Automation Conference” (or as we called it, Office Automaton Conference) in 1982 at San Francisco’s Moscone Convention Center. We paraded outside in our satirical VDT heads and other costumes, and befuddled attendees with what they assumed was a crude Luddite message against computing, but was actually our typically nuanced critique of wage-labor and corporate control over technologies—their design, purpose, and implementation. As we wrote at the time, “the ruling image-makers have things so well in hand that the terrifying absurdity of most modern work still seems normal to most people, and “technology” remains an unstoppable Monolithic Monster to be embraced or blindly rejected. For us the real point is not to do office work less speedily or more safely, or to have more say over how it’s allocated, nor even—in the long run—to get more money for it. The real point is: why do it at all? What is the purpose of all this office work?”

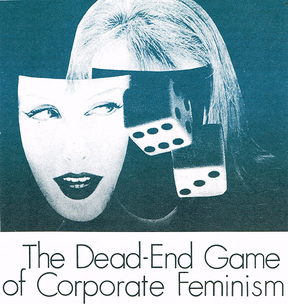

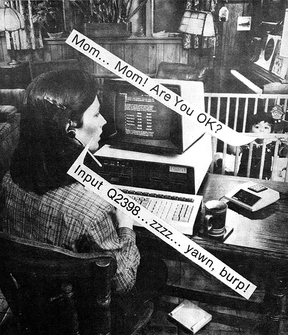

From the early years on we had a strong feminist bent. Many women were part of the collective during its life, and recurrent articles and graphics took on corporate feminism long before Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg advocated “leaning in,” as a corporate climbing strategy for upwardly mobile women. The reality that a new kind of high-tech peasantry was being established by the possibilities of telecommuting occurred to us well before it became a common experience. Home-based computer work meant diminished attention for children, something we joked about, but also dedicated the whole of issue 14 to analyzing.

In our first special issue on “sex” Michelle La Place took on corporate feminism and concluded, after citing many personal experiences of degradation and mistreatment by her female corporate overlords, that “feminism had become the darling of pop culture and big business… capitalism and the false sense of privilege and power it conveys actually perpetuates relationships of domination under which men and women can never be free.”

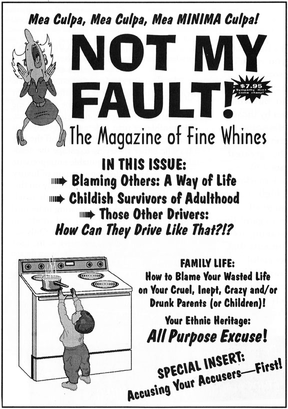

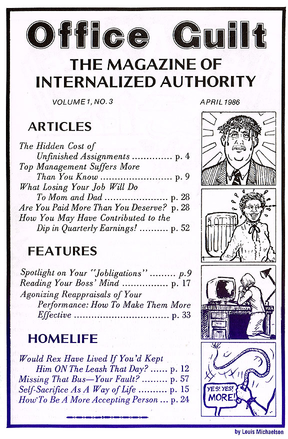

As a magazine project, we couldn’t help but invent new satirical publications that we imagined captured the reality of the world around us. Office Guilt magazine and Not My Fault magazine both struck at the quivering inner life of office workers, so often complicit, obsequious, blaming, and whiny.

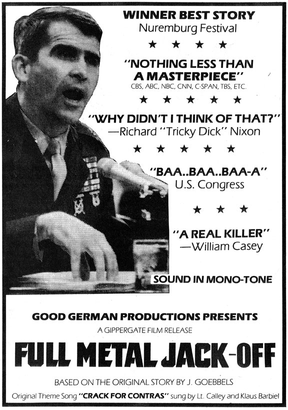

Though we tried to stay focused on our commitment to daily life at work, we found our attention widening to take in the Imperial follies of the U.S. government, both domestically and internationally. The U.S. government from Reagan through George H. W. Bush Sr. to Bill Clinton and George Bush Jr. was rife with scandal and corruption. The continuity from one regime to the next is often overlooked, too, in the domestic drama of partisan politics. But there is much more consistency than disjuncture in U.S. ruling circles. Oliver North led the clandestine efforts to sell weapons to Iran and use the money to finance the Contra War against Nicaragua. We used the Vietnam War-glorifying film “Full Metal Jacket” as the prompt led to this satirical send-up:

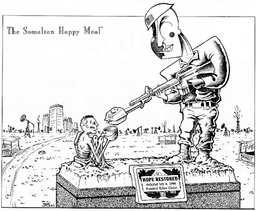

George H.W. Bush proclaimed a New World Order at the UN, and used this self-righteous proclamation to invade Iraq, while Clinton bombed Somalia, and both carried out a number of military interventions. Jim Swanson captured the hypocrisy of U.S. foreign policy in this era with this one:

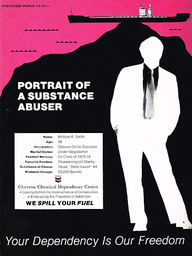

Some of our best efforts showed up on back covers. On the back of issue 22, our Ecology-themed issue, we lampooned an ongoing series of anti-drug use advertisements by replacing the narcotics with the substance that the entire modern world finds itself helplessly dependent on, oil. Chevron, based originally in San Francisco (now in the suburbs), was a frequent target of our barbs:

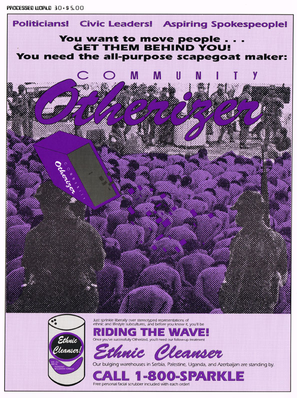

With the ongoing scapegoating of immigrants, not just in the U.S. but across the world, our back cover on #30 in 1992 advertised two vital products that any modern politician would need, Community Otherizer and Ethnic Cleanser:

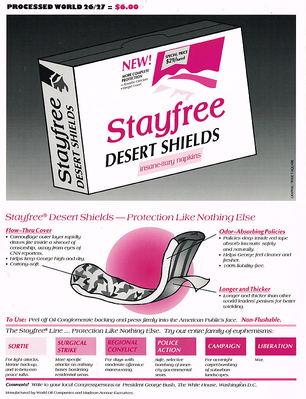

In the wake of the first Gulf War in 1991, we produced our only double issue, #26-27, which had a lot of material on the war, as well as the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact. The back cover punctured the absurdly named war “Operation Desert Shield”:

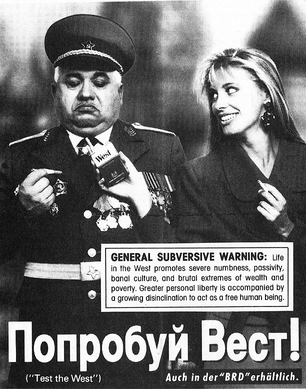

This ad was on a magazine we picked up during a trip through Eastern Europe just after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990.

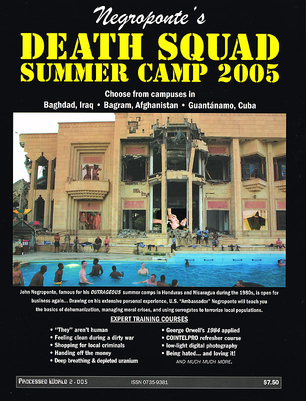

Years after Processed World stopped publishing (1994), we were coming on the 20th anniversary of the first issue in 2001. Some of the original contributors came together to produce our epic issue on the “Greatest Speedup in Human History.” We had so much fun making that issue that we decided to keep going. But the ensuing and absolutely last issue of Processed World (2005) took a couple of years and by the time it came out, nearly everyone had fallen out again, and only two of us were left to see it through. All in all it was a good issue, though, and this back cover showed we hadn’t lost our edge even all those years later:

Processed World thrived at the beginning of the Neoliberal turn. As such, it documented both a weakening official labor movement, and a new experience of daily work life that would come to dominate the early 21st century. Far ahead of its time in anticipating the kinds of peculiar alienations that afflict the isolated, atomized modern worker, it has not yet seen its manic radicalism fully realized in the nascent rebellions percolating at Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon and the rest. Who knows? Maybe the ideas we sketched out three decades ago couldn’t have found their full development until the world we anticipated took over much more of our daily lives. Peering into screens in our palms, on our laps, and on our desks, we probably won’t find a way out. But by banding together with the real people we share this predicament with, these tools can be put to rather dramatically different uses. The technical skills so widely admired and often well-paid are wasted on pointless bullshit that are shrinking our lives to isolated despair. Our anguish and sense of aloneness only increases when we are bombarded with the self-congratulatory propaganda that claims an ever more open, larger, and more generous world. The work we do is making the world we live in. We are coerced by student debt and exorbitant rents to think there is no alternative to this madness. But the alternatives are all around us, working in the next cubicle, the next building, the next company. They are us. Together we can make a radically better life, but we have to decide what we do, why, how, with whom, and how it fits with the natural systems on which we depend… in other words, basic issues of everyday democracy not just in the abstract political realm, but in the everyday life of work.

Processed World was an underground magazine that published 32 times in San Francisco from 1981-1994, plus an issue 33 1/3 that was never printed but is online, and with additional issues appearing in 2001 and 2005. An anthology of the first 20 issues, Bad Attitude: The Processed World Anthology, was published by Verso in London in 1990. All of the issues are online at archive.org and are free to download and use.

Featured in Logout! (#8)

author

Chris Carlsson

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Technology and The Worker

by

Wendy Liu,

Marijam Didžgalvytė

/

March 30, 2018