How to build an indefinite strike

by

The University Worker

December 14, 2022

Featured in Hot Strike Summer: View from the Picket Line (#15)

Strategies for building the action

bulletins

How to build an indefinite strike

by

The University Worker

/

Dec. 14, 2022

in

Hot Strike Summer: View from the Picket Line

(#15)

Strategies for building the action

Indefinite action means calling a strike without stating in advance when it will end. This means the strike could last one day (although that’s a bit unlikely) or as long as it takes to win. The calling of limited strike days is a relatively new phenomenon, although it has become the most common way of organising industrial action in Britain today. Previously, many workers would go on strike until demands were met.

We are currently going through the most intense period of industrial action in decades. As can be seen from Strike Map, there are picket lines being formed across the country in different sectors - some of which haven’t seen industrial action in a very long time. The feeling of anger seen on UCU picket lines is matched with a wider mood of strikes being called. Our successful aggregated ballot means we currently have strike mandates for all 150 higher education institutions in the UK, representing a huge amount of industrial leverage. It is vital that we use this moment, as well as our unprecedented mandate, to push ahead in the dispute.

Strikes are always a countdown on two sides. First, counting down how long can the employer go on with the economic disruption of the strike. Second, counting how long workers can last without being paid. When unions call limited strike days, the countdown is cut short. Instead, short strikes provide a rallying point for campaigns. They are a show of force - and if effective enough they can sometimes bring employers to the negotiating table.

An indefinite strike starting in February - following on the heels of a January Marking and Assessment Boycott - will start that countdown. This means we need to think seriously about the different countdowns on each side.

On the employer’s side, this means increasing the pressure from no assessment marks being released from the start of term. This can then be followed by the cranking up of pressure as teaching, administration, and other parts of the university don’t happen. There is a term’s worth of disruption to follow, as well as the next round of assessments.

Universities may be able to brush aside a few days’ strike, but a longer period of action is different. It gives the opportunity to find more ways to leverage the action, whether that is joining up with other unions, building a campaign with students, or targeting the leadership of universities and UCEA.

On our side, the countdown of how long we can last is, of course, very important. This is never a static number that can be calculated in advance, but depends on a range of factors. Clearly, inflation and the cost of living crisis puts increased pressure on members staying out on strike. This is also a pressure for losing days and weeks pay at a time with no victory.

There are many things we can do during the dispute to slow our countdown. The most obvious is claiming from the strike fund. Despite some confusing messaging, there is a substantial strike fund and cash surplus in UCU. As James Brackley (running for UCU treasurer) has noted, the UCU has cash reserves of upwards of £30 million. While this would run down quickly - previous aggregated disputes have cost £250,000 a day - it’s an important starting point for supporting an indefinite strike. If we’re not going to use this money now, when would we? Inflation is already eating away at any cash reserves.

In addition to this, we can ask for donations and solidarity from beyond the union. Some branches have already been holding fundraising parties and other creative ways to do this. At a local level, this means finding ways to support each other and keep turning out to the picket lines. The picket lines can be about more than just stopping scabs, but can also be a point where we support each other.

While some have expressed the impossibility of an indefinite strike being maintained, this doesn’t line up with many real life experiences. Just a few days ago, faculty at the New School in New York announced a tentative victory after three and a half weeks of indefinite strike action. Workers at the University of California have been on indefinite strike for over a month - with the lowest paid workers being the ones pushing for strike action to continue until a decent offer is made. These experiences flip the argument that indefinite strike action is only possible for privileged academics; rather, it is necessary in order to win for those in the most precarious situation in our institutions.

There are some aspects of this dispute that we cannot control, but there are parts we can plan for and try to change. This means taking seriously how we speed up the countdown for the employers, while slowing our own down. We have until May to make the most out of the leverage we currently have, before having to reballot for further action.

In order to make the most of this, we need to get planning for the action now. Regardless of the drama unfolding at the top of the union, it will be members at the rank-and-file who can push this dispute forward and carry out a successful strike. An indefinite strike gives us a high degree of flexibility, which enables us to be responsive to the developments of the negotiations in “real-time” as they happen. It will also make coordinating actions with other unions logistically much easier.

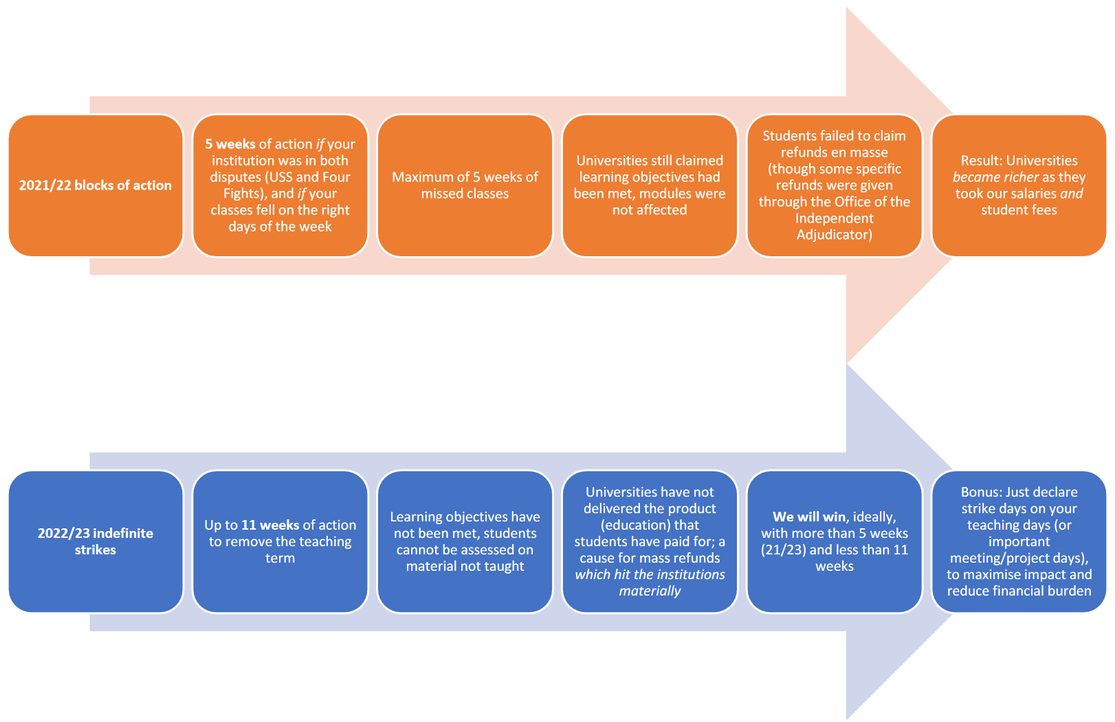

A rank-and-file member put together this diagram to show the differences between taking blocks of action and indefinite strikes:

What next?

From now until the start of the action, we invite more contributions to The University Worker that focus on indefinite strikes.

We want to focus on the questions: how do we weaken the employer or strengthen our side during the indefinite action? If we can do this, there is no reason that the action has to stay indefinite, but instead can lead to definite victories.

<style> .button { border: 4px solid #000000; border-radius: 24px; color: #000000; background-color: #FFFFFF; width: 50%; padding: 15px 32px; text-align: center; text-decoration: none; display: inline-block; font-size: 16px; margin: 4px 2px; cursor: pointer; box-shadow: 0 8px 16px 0 rgba(0,0,0,0.2), 0 6px 20px 0 rgba(0,0,0,0.19); } .button:hover { background-color: #FF0000; color: #000000; } a:link { text-decoration: none; } </style>author

The University Worker

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The University Worker: Day 3, 2022

by

The University Worker

/

Nov. 29, 2022