Hilde Weiss - Die “Enquête Ouvrière” von Karl Marx (1936)

theory

Hilde Weiss - Die “Enquête Ouvrière” von Karl Marx (1936)

by

Hilda Weiss

/

July 9, 2022

in

Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry

(#14)

Chapter Ten

Hilde Weiss’ essay was first published in Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung, the journal of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, in 1936. The reproduction below is the first complete English version of Weiss’ essay, translated by Maciej Zurowski.

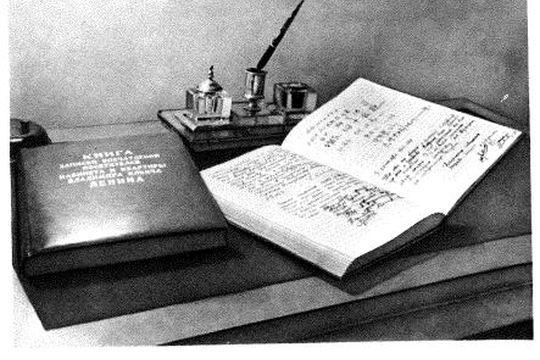

It appears from Marx’s letter of November 5, 1880, addressed to Sorge that the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ published in the Revue Socialiste on April 20, 1880, was the work of Marx himself. He writes: “I have prepared for him [Benoît Malon, the editor of the Revue Socialiste] the Questionneur [sic] which was first published in the Revue Socialiste and afterwards distributed in a large number of copies throughout France.”1 Only the detailed questionnaire, containing a hundred questions, and the accompanying text seem to have survived. A note in a later issue of the Revue Socialiste, the style of which suggests that it may have been written by Marx, indicates that some replies had been received, and that when a sufficient number had come in they would be published.2 The journal Egalité, which was published during this period, and which Marx described in the same letter to Sorge as the first “workers’ paper” in France, repeatedly urged its readers to take part in the survey and included copies of the questionnaire.3

Marx created an important document with this survey shortly after the Marseilles Socialist Congress of 1879. As he related in his letter to Sorge, it would contribute to the constitution of the “first real workers’ movement in France”. After years of the French socialist movement’s splintering into various groups and tendencies, after years of operating under the most severe illegality since the days of the Paris Commune, the “revolutionary collectivists”, the Guesdists, the Blanquists and the followers of Proudhon agreed on a programme and achieved the first great success in Marseilles, which laid the foundations for the formation of a “workers’ party”. It was characteristic of this period, in which the workers’ movement broke from the radical socialist petty-bourgeois tendencies, that after the congress of Marseille two organisations were initially formed in parallel: one that only admitted working-class members in order to make the contrast to the ruling class most explicit (‘Federation du parti ouvrier’) and a second that allowed socialists who were not workers to join (‘Federation des groupes socialistes’).4 Both organisations pursued the same goal: they wanted to make the working class stand on its own feet by completely breaking with groups that believed in the possibility of reconciliation or liberation by the ruling class. Around 1880, Marx set the French workers’ movement the principal task of creating a workers’ party, of confining itself to its own strength and of developing it. The ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ was meant to serve the same purpose, inviting the workers to describe their own social condition, which until then had only been undertaken by members or representatives of the propertied class. Marx did not intend the survey to merely represent a collection of facts: rather, the working class was to draw strength and knowledge from understanding its own working and living conditions. This would help it to solve the tasks leading to its emancipation.

Conceiving of his ‘Enquête’ in this way, Marx deliberately set it in contrast to the social surveys of his time, which were carried out by the French state and by scientific organisations or philanthropists on its behalf. The strong charge he levels at the French state in the introduction is indicative of this: he accuses it of having commissioned inquiries in various fields when political upheavals called for it, but never any serious investigation into the condition of the working class. The introduction furthermore describes the monarchical English government’s commissioning of social surveys and its policies on workers’ protection legislation as a model to be followed. In view of Marx and Engels’s fundamental criticism of English social legislation and their exposure of social grievances in England, for which they had accused the state as being partly responsible, these remarks in the introduction were bound to come across as a mockery of the French Republic.

And indeed, while in England the state had parliamentary inquiry panels and civil servant factory inspectors draw up comprehensive reports on the working conditions of factory workers, especially women and children, socio-political inquiries carried out directly by the state were a rarity in France.5 In 1848, the Comité du Travail of the Assemblée Constituante commissioned the first social survey of agricultural and industrial work conditions, whose findings were viewed as completely inadequate by public opinion.6 The questions were too general and theoretical, thus failing to give any genuine idea of the actual conditions. The second major state enquiry on working conditions, undertaken in 1872 by a parliamentary inquiry panel and addressed to the presidents of the chambers of commerce and prefects of the individual departments, stood out for its detailed account of the history of labour relations in France since 62 BC, yet its description of the contemporary social living conditions of the working class left much to be desired. Nonetheless, the investigation exhibited signs of great progress: it contrasted reports by officials and industrialists with the contributions of various workers’ delegations to the World’s Fairs in London (1862), Paris (1867) and Vienna (1873), which served as witness testimony, so to speak – and it granted the workers’ criticisms much space in the report. The commission had set itself the task of identifying the influences that had given the workers socialist ideas. It wanted to understand what feelings and ideas of the workers the socialist movement leaders had been able to draw on, and ultimately investigate changes in the development of French industry.

Apart from such isolated inquiries conducted by the state itself, a number of investigations were carried out on behalf of the state or by state institutions. The Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques became the commissioning body for a whole series of such research projects.7 The first person to be commissioned by the Académie to investigate the social conditions in French industry was the physician Villermé. His independently conducted enquiry, Tableau de l’état physique et moral des ouvriers from 1835, compiled important details about the situation of industrial workers in the cotton, wool and silk industries outside Paris, serving both Buret and subsequent surveyors as a source for their own research. Buret’s study De la misère des classes laborieuses en Angleterre et en France, published in 1840, was also carried out under the auspices of the Académie and won an award there, even if the jury did not agree with Buret’s fundamental criticism or with his demands: unlike Villerme, Buret openly sided with the workers. Of all the writings published by the Académie in connection with the revolution of 1848, Villermé’s Associations ouvrières and Adolphe Blanqui’s survey Les classes ouvrières en France pendant l’année 1848 deserve particular mention.8 On the occasion of Villermé’s death, his text, in which he takes a stand against the workers’ associations, was described by Naudet as a ‘crusade in defence of a society threatened by socialism’. Similarly, the economist Blanqui was asked by the Académie to use his survey to contribute to the restoration of the shattered order. He himself described the objective of his investigation as an attempt to demonstrate the following: if real misery exists in France, this misery cannot be separated from human weakness – and moreover, it is everywhere mitigated by the progress of morals and institutions.9

Around the same time as the surveys encouraged by the Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques, a number of similar inquiries appeared. They were partly launched by social organisations (charitable societies, welfare associations, mutual aid associations etc.) and saving banks, while others were undertaken by philanthropists and humanitarian doctors independently. These efforts aimed to show the charitable effect of social institutions of all stripes, from savings banks to pawnshops (Monts de Piete) to the collective resettlement of workers to the countryside, for which the state and the municipalities demanded support. Like the publications of the Académie, they were at the same time directed against the ascending workers’ movement and its socialist theories, against all attempts of the working class to emancipate itself, and against cooperatives and trade unions. Apart from Villermé, we shall only cite the most important of these reformers and philanthropists: Baron de Morogues,10 Baron de Gérando,11 Villeneuve-Bargemont12. The most important among them was probably Vidal, who was also closest to socialism.13

The purpose of both the official and private enquiries was to alert the government to the consequences of rapid industrialisation and unbridled competition in the first third of the nineteenth century. Like the utopians, the philanthropic reformers (to whom all the cited authors of surveys, with the exception of Buret, belonged) saw the bad sides of ascending capitalism – that is, the hardship and misery of the industrial workforce. The workers, especially their wives and children, who were the most vulnerable to the excesses of the factory system, inspired pity and disquiet in them. Consequently, they depicted the social and especially moral effects of the immiseration of the proletariat – but the causes of misery did not occur to them, nor did the idea of eliminating them. In their plans, suggestions and reform schemes, they appealed to both classes: they advised entrepreneurs to be more considerate in their zeal for production and workers to lead a more morally upright life and reduce the birth rate. Moreover, they pleaded to the state to improve social conditions, introduce reforms in the field of private and public charity and pass state legislation on factories. A characteristic example of the nature of these surveys is the objective of Gerando’s book set by the Académie de Lyon: “The aim is to determine the means by which true need is recognised and to ensure that alms benefit both those who give them and those who receive them”. Vidal, by contrast, aptly criticises the humanitarian reformers (though his criticism could also apply to some of his own proposals): “The pauperists and philanthropists have carefully analysed the effects of misery and described them in detail. Then they have advised alms and charity to the rich and patience, devotion, moral restraint and thrift to the poor (that is to say, austerity for people who do not even earn the bare necessities of life).”14

Since the organisers of these studies had no intention of changing the existing economic system, but only wanted to alleviate social misery as much as was possible within the framework of that system, their interest in exposing social ills had its limits. At times, they even felt that it was desirable to conceal the real situation, namely when there was a danger that the workers would no longer be satisfied with welfare and palliatives and instead act on their own initiative to improve their situation. The interest of surveyors before Marx in describing the real social conditions went as far as the existing social order was not challenged and it seemed advantageous to pacify the workers, who were deemed vulnerable to the influence of socialist theories. Thus, the rapporteur of the official survey of 1848, which had been commissioned under the pressure of the revolutionary events, exhibited an overtly hostile stance towards the workers.15 The findings of the survey were completely inadequate since the priority of its organisers was not the elimination of social misery, but the stabilisation of the shattered state institutions (“le besoin de stabilité des institutions”). And so, the enquiry found that the condition of the workers was quite acceptable. The objective of the 1872 survey clearly delineates the limits that the organisers had set themselves for their investigation: “The need to research and learn about the needs of workers in order to meet them within what is just and possible”. On one side, a barrier dubbed the “measure of the possible” – i.e. reforms that could be attained by the government – kept the surveyors in check, while on the other, there was their intention to study the causes of working-class sympathy for socialist ideas as well as their traction. A closer relationship between industrial and agricultural labour was recommended as a result of the survey: this would distance the workers from socialist influences and help to raise their morale. Furthermore, it was argued that labour peace, which according to the investigation appeared to have been shattered in some places, could only be restored by reinforcing the patriarchal stance of the entrepreneur and increasing his sense of responsibility towards his workers.

Nor were private surveyors, whose objectives were limited by their conservative Christian or liberal views, interested in a truthful depiction of social conditions.16 Audiganne, who himself had authored a number of studies on the situation of workers, tried to find the causes of the inadequacy of all these surveys: “… It is not the fault of the surveys, which by their nature ought to shed more light on all the questions covered than any other investigation. The error stems from the method followed in carrying out the surveys or from ulterior motives that had crept in”.

II

Marx’s ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ differs in three respects from previous investigations of social conditions. First, as is clear from the statement of its purpose, and from the questions themselves, it aimed to provide an exact description of actual social conditions. Secondly, it proposed to collect information only from the workers themselves. Thirdly, it had a didactic aim; was meant to develop the consciousness of the workers in the sense expounded in Marx’s social theory.

Marx also intended that his ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ should diffuse among the general public a knowledge of the working and living conditions of the workers, and he had, therefore, some ulterior motives in undertaking his study. At the same time, however, his socialist views imposed upon him the obligation to depict as faithfully as possible the existing social misery. He assigns to social investigation the task of aiding the workers themselves to gain an understanding of their situation. For philanthropists the workers, as the most miserable stratum of society, were the object of welfare measures; but Marx saw in them an oppressed class which would become master of its own fate when once it had become aware of its situation. With the development of industrial capitalism, not only the misery of the proletariat, but also its will to emancipation increased. In his preface to the questionnaire Marx describes the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ as a basis for “preparing a reconstruction of society”.

However, it is not only in its aims that Marx’s ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ differs from the private and official investigations that had preceded it, but also in the manner in which it was carried out. Earlier surveys, even if they had the intention, could not discover the real character of social evils, because they employed inadequate means to collect their information. They were addressed almost exclusively to factory owners and their representatives, to factory inspectors where there were such people, or to government officials (as in the case of Villeneuve-Bargement’s inquiry).17 Even where doctors or philanthropists who made such surveys went directly to working-class families, they were usually accompanied by factory owners or their representatives. Le Play, for example, recommends visits to working class families “. . . with an introduction from some carefully selected authority”; and he advises extremely diplomatic behaviour towards the family members, including the payment of small sums of money, or the distribution of presents, as a recompense. The investigator should “. . . praise with discrimination the cleverness of the men, the charm of the women, the good behaviour of the children, and discreetly hand out small presents to all of them.”18 In the course of a thorough critical examination of survey methods that appears in Audiganne’s account of the discussions in his circle of workers, it is said of Le Play: “Never was a more misleading course embarked upon, in spite of the very best intentions. It is simply a question of the approach. A false viewpoint and a false method of observation give rise to a completely arbitrary series of suppositions, which bear no relation whatsoever to social reality, and in which there is apparent an invincible partiality for despotism and constraint.”19 Audiganne indicates as one of the common mistakes in the conduct of surveys the pomp and ceremony which is adopted by investigators when they visit working-class families. “If there is not a single tangible result produced by any survey carried out under the Second Empire, the blame must be assigned, in large measure, to the pompous manner in which they were conducted.”20 Marx and Engels also described the methods by which workers were induced to give testimony through social research of this kind, even to the extent of presenting petitions against the reduction of their working hours.

Marx’s questionnaire, which was addressed directly to the workers, was something unique. The article on social surveys in the Dictionary of Political Economy observes bluntly: “Those who are to be questioned should not be allowed to participate in the inquiry.”21 This justified Audiganne’s criticism that “. . . people judge us without knowing us.”22

Marx asks the workers alone for information about their social conditions, on the grounds that only they and not any “providential saviour” know the causes of their misery, and they alone can discover effective means to eliminate them. In the preface to the questionnaire he asks the socialists for their support, since they need, for their social reforms, exact knowledge of the conditions of life and work of the oppressed class, and this can only be brought to light by the workers themselves. He points out to them the historical role which the working class is called upon to play and for which no socialist utopia can provide a substitute.

This method of collecting information, by asking the workers themselves, represents a considerable progress over the earlier inquiries. It is, of course, understandable that Marx had to restrict himself to this method. Apart from the political and educational purposes which he wanted to combine with his investigation, his method of obtaining information directly from the workers was intended to open the eyes of the public and of the state. From the point of view of modern social research in this field, the restriction of such an inquiry into working conditions to the responses of workers themselves would be considered inadequate. This method of inquiry is still vitally important in modern social surveys; but the monographs that were to have resulted from the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ would need to be complemented, and their findings checked, by statistical materials, and by the data available from other surveys.

The didactic purpose of the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ arises, as will be shown later, from the arrangement and formulation of the questions; but it is apparent also in the preface, and especially in the title that Marx gives to the monographs which it is proposed to write on the basis of the replies to the questionnaire; he calls them cahiers du travail (“labour-lists”) in contrast to the cahiers de doléances (“grievance-lists”) of 1789. The specific character of his survey is shown by his coining of this new term, which is connected with a living tradition of the French workers, the petitions of the Third Estate. But while the cahiers de doléances put forward trivial demands in a servile manner, the cahiers du travail were meant to contain a true and exact description of the condition of the working class and of the path to its liberation. Moreover, the accomplishment of this program is not to be left to the goodwill of a king; the workers are to struggle forthrightly and consciously for their human rights. It is not by chance that Marx also refers in this context to the “socialist democracy,” whose first task is to prepare the “cahiers du travail.” The workers, who have to wage a class struggle and to accomplish a renewal of society, must first of all become capable of recognizing their own situation and of seeing the readiness of individuals to work together in a common cause.

The cahiers du travail, as I have noted, were not only to provide a better knowledge of working-class conditions, but were also to educate the workers in socialism. By merely reading the hundred questions, the worker would be led to see the obvious and commonplace facts that were mentioned there as elements in a general picture of his situation. By attempting seriously to answer the questions, he would become aware of the social determination of his conditions of life; he would gain an insight into the nature of the capitalist economy and the state, and would learn the means of abolishing wage labour and attaining his freedom. The questionnaire thus provides the outline of a socialist manual, which the worker can fill with a living content by absorbing its results.

Several of the questions are formulated in such a way-for instance, by the introduction of valuations that the worker is led at once to the answer which the didactic purpose of the survey requires. Thus, Marx refers to the misuse of public power when it is a matter of defending the privileges of entrepreneurs; and a subsequent question asks whether the state protects the workers “against the exactions and the illegal combinations of the employers.” The contrast is intended to make the worker aware of the class character of the state. Another example is provided by the case where workers share in the profits of the enterprise. The respondent is asked to consider whether business concerns with this apparently social orientation differ from other capitalist enterprises, and whether the legal position of the workers in them is superior. “Can they go on strike? Or are they only permitted to be the humble servants of their masters?” (Question 99). It should be said, however, that only a relatively small proportion of the questions seek to influence opinion so directly.

It is far more significant, in relation to the two aspects of the survey, that Marx was successful in setting out the questions in a clear and practical manner. They are easily intelligible and deal with matters of direct concern to the worker. The simplicity and exactness of the questions in the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ represent an advance over earlier surveys. Audiganne had observed quite rightly that these surveys asked questions that were far too comprehensive, abstract, and complicated, and compromised the answers on important issues by introducing irrelevant questions.23 For the same reasons, the various private investigations could provide no better picture of the real social conditions and attitudes of the workers.

The content of the questions posed in the earlier surveys, as well as their aims and techniques of inquiry, corresponded very closely with the interests of employers. For example, the question whether workers were paid wholly in cash, or whether a part of their wages were given in the form of goods or rent allowances, was asked both in the government survey of 1872 and in the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’; but in the former case it was asked from the point of view of the employers, in the latter from the point of view of the workers. In the official survey, payments in the form of goods are treated as a “supplement” to wages, but Marx regards every form of wage payment other than in cash as a method of reducing wages.

Since Marx’s survey does represent an advance over earlier attempts, it is all the more surprising that very few replies to the questionnaire were apparently received.24 Two reasons may explain this failure: first, the scope of the questionnaire, and second, the circumstances of the time. Even today, it is not easy for the average worker, in his spare time, to answer a questionnaire containing a hundred questions; and it was all the more difficult in a period when workers were being asked to do this for the first time. Their ability to write and to express themselves was still limited; they read very little, and their newspapers were published in small editions, as well as being hampered by the censorship. Second, the French labour movement was still in the period of depression that followed the Paris Commune. Had there been at that time an independent labour movement, the survey could have been carried out much more effectively. It was, indeed, because of the backwardness of the labour movement and of the working class generally,25 that Marx gave his survey the didactic purpose of awakening the workers to a realization of their condition. Thus Marx’s survey had at the same time to create the circumstances in which an inquiry could be carried out. One could only evaluate its real success or failure if, say, a similar survey had been conducted again a few years later.

The structure of the questionnaire derives from the combination of its two objectives. It comprises four distinct sections: workplace health and safety; working hours, women’s and children’s work; wages and unemployment; organisation and struggle. The questions follow the worker through his entire working life and show him how the different aspects of his everyday life are connected and what general laws they are subject to.

The first questions deal with the geographical location of the enterprise, its machinery and the degree of division of labour. This is followed by the statutory control of occupational health and safety, which in the last instance is the responsibility of the state. Question 17 concerns whether there is a state or municipal institution to monitor the hygienic conditions in the factory, or whether the employer is legally obliged to compensate the worker in the event of an accident. The following questions about child labour and child rearing likewise focus on the existence and actual application of laws (39, 40). The inadequacy of legislation to protect workers is highlighted. Why can employers circumvent or simply ignore laws? The worker learns the reasons for this from the two subsequent questions: what penalty awaits the entrepreneur in the event of a breach of contract, and what penalty awaits the worker (48, 49)? Based on many small personal experiences and those of his colleagues in the workplace, the worker, having now become aware of the general significance of these daily conflicts, begins to understand the ‘class character’ of the state. And if answering these questions has not yet made him grasp the bigger picture, Marx confronts him with the disinterested or hostile attitude of the state towards the worker especially questions 92 and 93.

In this way, Marx wants to undermine the workers’ confidence in the existing state. At the same time, he tries to challenge theories of the state that had gained a foothold in the working class at the time, opposing both Bakunin’s anarchism and Louis Blanc’s belief in the ‘omnipotence’ of the state.

A particularly long section is devoted to discussing the social position of the entrepreneur. First, the worker is told that the function of the capitalist entrepreneur remains the same even in a joint-stock company. The next questions are designed to highlight the fact that the entrepreneur, although responsible for safety measures, would probably rarely compensate workers suffering an accident “while working to enrich him” were it not for state coercion (22, 23, 26, 27). Indeed, he speaks of the entrepreneur’s “domination over wage labourers” and examines the operational and penal regulations that serve to secure his domination. Noting that the state intervenes against workers’ attempts to form associations – they did not gain the right to create trade unions until 1884 – but tolerates secret employer associations, Marx asks whether there is any knowledge of such employer associations and describes their function in the class struggle.

Next, Marx addresses the “exploitative function” of the entrepreneur, providing an inductive bridge to his theory of surplus value. The answers to these questions are to show to what degree the process examined by this theory is perceptible to the worker and actually recognised by him. First, Marx lists a series of measures that increase the absolute surplus value by extending the working day: shorter lunch breaks (33, 34, 35), overtime for cleaning of machinery (43), night work (36, 41), overwork due to cyclical or seasonal upswing (42, 52). There is also mention of the fact that factory workers are compelled to do additional work on the side if low wages, which are common in rural areas, are not enough to make ends meet (11). Efforts to maximise relative surplus value by increasing labour intensity are also addressed in two questions (78, 79). Further ways of cutting wages are dealt with in detailed questions on penalties for lateness (44) and various cheating practices in the calculation of piecework wages (56, 57). Marx then points out that it is actually the workers who are lending the entrepreneur their respective wages in advance: as they are waiting for their pay, they often have to take out loans at high interest rates (e.g. at pawnshops) (58), and if the company goes bankrupt, they can lose large amounts of money in this manner (59). There are also very detailed questions concerning the wages of other family members and the wage systems applied. (53–57, 62–66). Some questions about household budget expenditure once again draw attention to loans, taxes and extra charges enforced by the entrepreneurs (69, 70). Such enquiries are used to clarify the concept of real wages, for it is here that losses of income become most visible to the worker (71). The end of the section deals with the impact of the crisis and with old-age unemployment (73–75, 77, 80, 81). Marx wants all these questions to warn the worker against the illusion of a harmony of interests, as well as against utopian schemes and reform proposals.

If the worker has travelled this far along the path indicated by Marx, he will have grasped to what kind of social order he has fallen victim. Consequently, a question arises for him: what can I do to improve my situation and liberate the workers? This last section of the questionnaire addresses the methods that workers can use to liberate themselves. The first question here concerns the existence of sociétés de résistance – surrogate trade unions of sorts, set up to provide financial support for strikes since the creation of trade union organisations was forbidden. Thus, trade unions are recommended to the worker as the first means of leading his struggle for emancipation. He is then prompted to report on any strikes that may have been organised, about their nature and causes (83–87). At this juncture, the worker is expected to come to understand the role of the prud’hommes, which were state institutions created to ensure industrial peace and which were composed of representatives of both employers and workers. In Marx’s view, this arbitration system is an obstacle to the independent organisation of the workers’ movement and its struggle. Question 89 underlines the importance of the solidarity strike in support of a movement in a related industrial sector. The following questions (90–94), which deal with the violent state response to workers in the event of labour disputes, are evidently meant to convey that purely economic strikes over wage demands will ultimately have to be raised to the level of political strikes. To conclude the survey, Marx criticises the support, pension and savings banks set up by employers, as well as the producer cooperatives and the system of workers’ profit-sharing (95–99). His rejection of these institutions has already been mentioned earlier. Here, Marx takes on Proudhon, Blanqui and Louis Blanc. His endorsement of trade unions is aimed on the one hand against Proudhon, who considers strikes and workers’ associations illegal and unacceptable, and on the other against Blanqui, who calls for the constitution of a conscious minority to lead the political struggle. Marx, in contrast to him, emphasises the need for comprehensive workers’ organisations and economic struggles to defend the interests of the oppressed class. Finally, he objects to Louis Blanc’s producer cooperatives because of their collaboration with the state and employers and because of their utopian character. Marx’s rejection of bourgeois attempts at reform is also aimed against the surveys of his predecessors, namely the philanthropists who recommended administrative improvements for the bourgeoisie as a remedy against the misery of the working class. In place of reforms to protect the existing order, and instead of the organisation of society according to schemes dreamed up by the utopians, Marx advocates the organisation of the proletariat as a class that necessarily emerges from historical development and that will ultimately bring liberation. The ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ serves the realisation of this goal too.

THE TEXT OF THE QUESTIONNAIRE26]

No government-whether monarchical or bourgeois-republican-has dared to undertake a serious investigation of the condition of the French working class, although there have been many studies of agricultural, financial, commercial and political crises.

The odious acts of capitalist exploitation which the official surveys by the English government have revealed, and the legislative consequences of these revelations (limitation of the legal working day to ten hours, legislation concerning the labour of women and children, etc.), have inspired in the French bourgeoisie a still greater terror of the dangers which might result from an impartial and systematic inquiry.

While awaiting the time when the republican government can be induced to follow the example of the English monarchical government and inaugurate a comprehensive survey of the deeds and misdeeds of capitalist exploitation, we shall attempt a preliminary investigation with the modest resources at our disposal. We hope that our undertaking will be supported by all those workers in town and country who realize that only they can describe with full knowledge the evils which they endure, and that only they-not any providential saviours-can remedy the social ills from which they suffer. We count also upon the socialists of all schools, who, desiring social reform, must also desire exact and positive knowledge of the conditions in which the working class, the class to which the future belongs, lives and works.

These “labour-lists” (cahiers du travail) represent the first task which socialist democracy must undertake in preparation for the regeneration of society.

The following hundred questions are the most important ones. The replies should follow the order of the questions. It is not necessary to answer all the questions, but respondents are asked to make their answers as comprehensive and detailed as possible. The name of the respondent will not be published unless specifically authorized, but it should be given together with the address, so that we can establish contact with him.

The replies should be sent to the director of the Revue Socialiste (Mon sieur Lécluse, 28 rue Royale, Saint-Cloud, near Paris).

The replies will be classified and will provide the material for monographs to be published in the Revue Socialiste and subsequently collected in a volume.

-

“Twenty-five thousand copies of this appeal were printed and were sent to all labor organizations, socialist and democratic groups, French newspapers and individuals who requested copies.” (Note on the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’ in Revue Socialiste, April 20, 1880). ↩

-

“Concerning the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’: A number of our friends have already responded to our questionnaire, and we are grateful to them. We urge those of our friends and readers who have not yet replied to do so quickly. In order to make the survey as complete as possible we shall defer our own work until a large number of questionnaires has been returned. We ask our proletarian friends to reflect that the completion of these ‘cahiers du travail’ is of the greatest importance, and that by participating in our difficult task they are working directly for their own liberation.” Revue Socialiste, July 5, 1880. ↩

-

“In its last issue the Revue Socialiste has taken the initiative in an excellent project… The significance of an investigation of working-class conditions as they have been created by bourgeois rule is to place the possessing caste on trial, to assemble the materials for a passionate protest against modern society, to display before the eyes of all the oppressed, all wage-slaves, the injustices of which they are the constant victims, and thereby to arouse in them the will to end such conditions.” L’Egalité, April 28, 1880. ↩

-

“It is certainly a splendid thing that a union of socialist groups is being formed alongside the workers’ party… But one must ensure that the [latter] association, whose basic lines were drawn up in Marseille, only admits workers. Only workers, but all workers of course. For the idea is to put the ruled class against the ruling class, create a rupture between the France that produces and the France that merely consumes… The basis of the workers’ association will be a community of suffering, whereas that of the socialist union will be a community of demands.” – Our translation, L’Egalité of 21 January 1880. ↩

-

See Hilde Rigaudias-Weiss, Les Enquêtes Ouvrières en France entre 1830 et 1848, Paris 1936. ↩

-

See Dictionnaire de l’Economie Politique, 1854 and Audiganne, Memoires d’un ouvrier de Paris 1871-1872, Paris 1873, pp. 39 et seq. ↩

-

The Académie des Sciences Morales et Politiques was created by the French Revolution. Suppressed by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1803 because of its “revolutionary aspirations”, it was only re-established after the July revolution. The Académie then changed its character completely and became a conservative, pro-state institution, which Cavaignac demanded in 1848 should participate in the defence of the social principles under attack. ↩

-

“Modest treatises were published, but the people did not buy them. Even the petty bourgeoisie read them with a certain mistrust – for the names Thiers, Dupin, Cousin, Bastiat, etc. reminded them of the partisans of the monarchy who had just been banished.” (La Grande Encyclopédie) ↩

-

Adolphe Blanqui, pp. 9–10. ↩

-

De Morogues: De la misère des ouvriers et de la marche à suivre pour y remédier, Paris 1832; de Morogues: Du Paupérisme, Paris 1834. ↩

-

De Gérando: De la bienfaisance publique, Paris 1839; de Gérando: Le visiteur du pauvre, Paris 1824; ↩

-

Villeneuve-Bargemont: Economie politique chrétienne, ou Recherches sur la nature et les causes du paupérisme en France et en Europe, et sur les moyens de le soulager et de le prévenir, Paris 1834. The motto was: “One must commend patience, modesty, work, sobriety and religion. The rest is only deception and lies.” – see the Résumé of the Enquête Villeneuves, vol. 2, pp. 590 et seq. ↩

-

Vidal: De la répartition des richesses, Paris 1846. ↩

-

Vidal: De la répartition des richesses, p. 461. ↩

-

In his Memoires d’un ouvrier de Paris, Audiganne makes a criticism of the enquiry that he describes it as the prevailing opinion of workers in the surrounding neighbourhoods: “The rapporteur, Monsieur Lefebvre-Duruflé, let slip a marked antipathy to the uprising.... There was an obvious lack of justice to the report” (p. 39, 45/46) ↩

-

See e.g. Blanqui, Des classes ouvrières en France, Paris 1849, p. 207: “The family disintegrates very rapidly when it comes into contact with the polluted air of the cellars of Lille or the attics of Rouen. It is better to throw a discreet veil over these sad dwellings than to make closer investigations here…”. ↩

-

[Villeneuve-Bargement, Economie politique chrétienne ou Recherches sur la nature et les causes du paupérisme en France et en Europe et sur les moyens de le soulager et de le prévenir, 3 vols. (Paris: Paulin, 1834)-Ed.] ↩

-

Les Ouvriers Européens, Vol. I, p. 223. ↩

-

Audiganne, Mémoires d’un ouvrier de Paris, 1871–1872 (Paris, 1873), p. 61. ↩

-

Audiganne, op. cit., p. 93. ↩

-

Dictionnaire de l’économie politique (Paris, 1854), p. 706. ↩

-

Audiganne, op. cit., p. 1. ↩

-

For one example among many, see Ducarre, Rapport sur les conditions du travail en France (Versailles, 1875), p. 195: “What is the physical condition of the working population in your district, from the point of view of sanitary conditions, population increase, and expectation of life?” It is easy to imagine the prolixity of the replies. ↩

-

It has proved impossible to find even the few replies that did arrive, in spite of an active search for them. ↩

-

The reports compiled by workers on the occasion of the Vienna Exhibition (1873) show clearly how far the workers at that time were influenced by utopian ideas and by the views of employers. ↩

-

[Hilde Weiss notes that this was, to her knowledge, the first German translation of the ‘Enquête Ouvrière’. The first English translation of the questionnaire and of some passages from the prefatory statement was published in T. B. Bottomore and Maximilien Rubel, editors, Karl Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology and Social Philosophy.-Ed.] ↩

Featured in Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (#14)

author

Hilda Weiss

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next