Glasgow Couriers Strike Against Pay Cuts

inquiry

Glasgow Couriers Strike Against Pay Cuts

by

Stan Mills

/

Sept. 18, 2018

When UberEats cut workers’ pay, they fought back

On Monday the 10th of September Glasgow Uber Eats couriers, organising through Couriers Network Glasgow, refused to work and held a protest outside of Uber offices in the centre of the city, joined by supporters from the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), Strathclyde UCU, and others. This is the boldest action yet by the Glasgow branch of the Couriers network, who have been steadily building a solid organisation since their formation in March.

Background

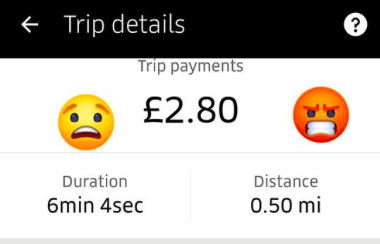

On top of a base rate of £2.80 an order, Uber Eats applies a bonus known as a ‘boost’, to top up couriers pay. The ‘boost’ varies over time and according to different areas of the city. It functions as a market-like mechanism to balance out labour supply and demand, ensuring couriers take jobs in out of the way, or quiet, areas. In reality, without boosts, the base pay rate is too low to earn a living, and Uber appeared to acknowledge this, keeping boosts in Glasgow at 1.3 or more (meaning, roughly, 30% on top of the base pay) even in busy areas of the city, until around a month ago.

Following another bad financial report and having finished their expansion across the whole Glasgow urban area, Uber have set upon steadily reducing boosts. In the last month the city centre has rarely had more than a 1.2 boost, often down to 1.1 in the daytime. This reduction in pay-per-drop made couriers angry. There is some evidence that, even before deciding to take collective action, this discontent was affecting Uber’s service, with queues of uncollected orders at McDonalds, and smaller restaurants complaining couriers were rejecting or cancelling their orders..

Last Thursday we logged on to find our app showed no boost whatsoever in large parts of the city. This meant that without managing three or more deliveries an hour it was impossible to earn minimum wage. Three deliveries an hour might not sound like much, but to achieve this we rely on luck - if an order isn’t ready on the our arrival at the restaurant, or we have to travel 10 minutes away just to collect an order, or the customer takes a while to answer the door, we’re likely to miss out.

While low key grumbling about boosts was the soundtrack of the summer, the disappearance of boosts on Thursday was the straw that broke the camel’s back. On our group chats, and waiting at the counter in McDonalds’, the couriers were angry and ready for taking action against Uber.

That evening it was decided that, with university freshers week (a big earner for Uber Eats), about to start, we would encourage couriers to log off on Monday afternoon, and gather outside of Uber Offices in the centre of the city. We spread the word through several worker group chats, and by distributing leaflets while working. Speaking from my personal experience, I had a chance to chat with around 7 or 8 couriers on Thursday night and all of them were angry and keen to be involved in any upcoming action.

On Friday afternoon, 36 hours after boosts vanished, Uber sent out a message through the courier app explaining that a ‘technical error’ had caused the issue, and in fact boosts were intended to remain at 1.1, meaning £3.20 a drop rather than £2.80. Boosts would reappear in the app by 4pm that afternoon, they explained, and we would be reimbursed for everything we had missed out on over the previous two days. On top of this several ‘promotions’ along the lines of ‘complete four deliveries between 18:00 and 20:00 to earn an extra £10’ were offered.

This ‘technical fix’ was overwhelmingly interpreted as an attempt by Uber to backtrack, and the promotions seen as a cynical attempt to salvage Uber-Courier relationships. Couriers were keen that the action should go ahead on Monday.

The Strike

At lunchtime on Monday we conscripted supporters from our local IWW branch to deliver letters to Uber Eats ‘restaurant partners’, explaining why couriers were angry, and why service might be slow that afternoon, and to request that they show support for couriers by either turning off their apps or sending complaints to Uber on our behalf. The idea was to spread the word about courier discontent, and in an indirect way, build some level of understanding with restaurant workers.

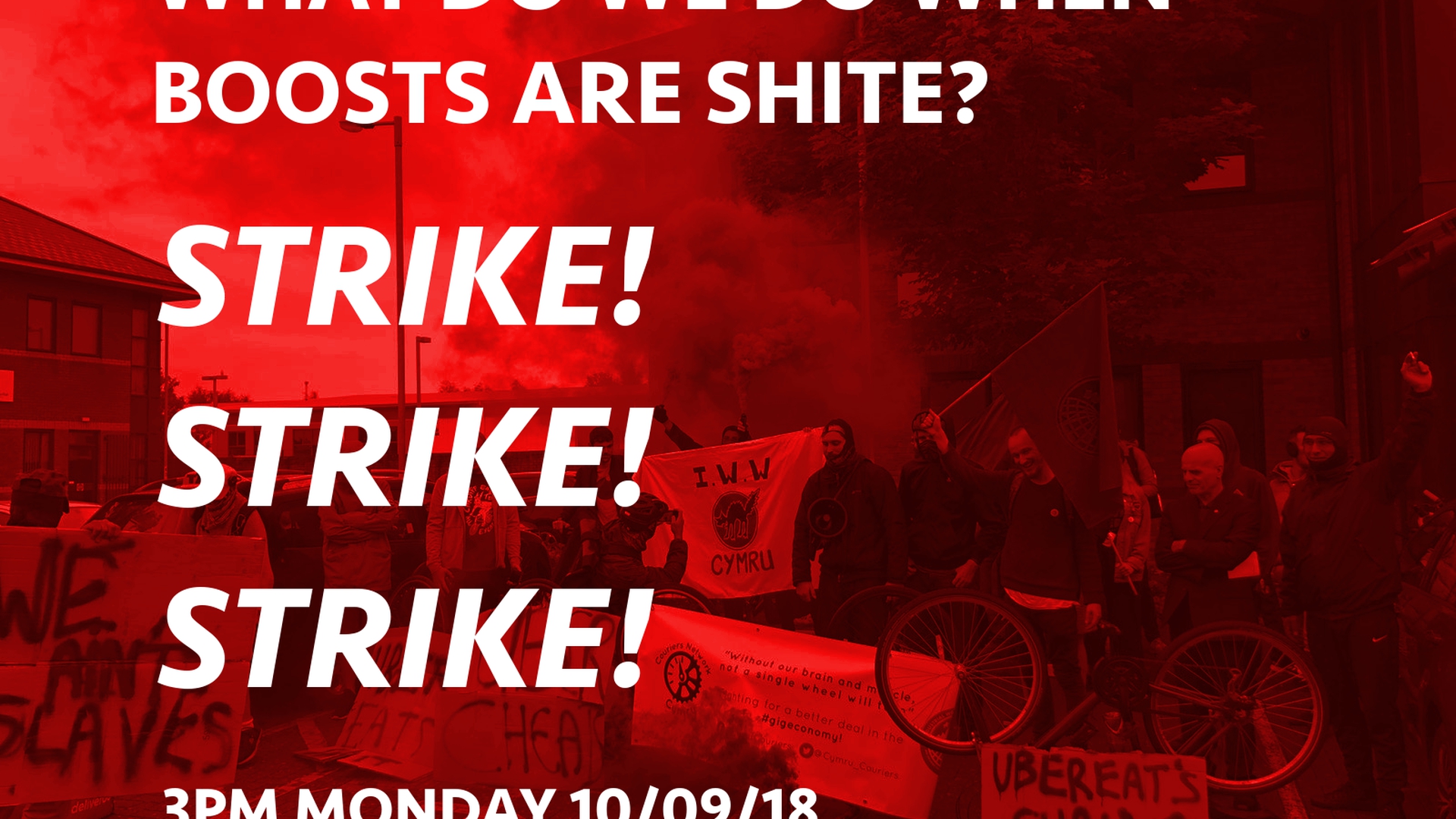

At 3PM on Monday, under the slogans “What do we do when boosts are shite? Strike! Strike! Strike!”, and “Four pounds per drop!”, wielding a cacophony of home made signs, and to a soundtrack of tangentially bike-related music, couriers began to gather outside Uber’s Glasgow office on Buchanan Street, a pedestrian thoroughfare on the city centre. We were joined by our affiliate union, Clydeside Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a delegation from Strathclyde University and College Union (UCU), and other supporters from various groups including the Scottish Education Workers Network (SEWN), the Revolutionary Communist Group (RCG), and even a visiting member of the Independent Workers of great Britain (IWGB).

Over two dozen couriers were present, most hiding their faces behind scarf’s or pound shop dust masks to hide our identity and prevent blacklisting. Other couriers who had not head about the action saw us on the streets and joined with us. We distributed several hundred flyers, explaining our grievances to a mostly sympathetic and supportive public, and making a whole lot of noise.

We hung around by the Uber office in the hope of catching the office staff leaving at four, but when we realised they either weren’t coming out or had snuck out the back, we proceeded to march down the street to a local McDonalds where many of our city centre orders come from, and continued chanting, playing music, and chatting with members of the public.

Moving Things Forward

As the drizzle turned to rain, around 15 couriers headed for a beer and a casual debrief. Spirits were high, and we discussed possible next steps. It was agreed that we should keep the pressure with some kind of event or action every Monday until boosts lower than 1.3 are done away with.

Other discussion topics included a collective zero-tolerance policy regarding waiting times, agreeing to encourage all couriers to cancel orders if they take more than 10 minutes to be prepared, producing merchandise to raise an emergency injury fund, a strategy used by bike couriers of old. We also discussed how, in line with the national courier network’s ongoing campaign, we might demand more transparency from Uber, in particular regarding contract terminations and access to data on how busy it is at a given time.

Throughout Monday’s action, we had made no attempt to approach Uber directly. We were satisfied that our demand of £4 minimum per drop had been heard, and that we showed them we could mobilize couriers and supporters at short notice. We would be well aware if our demands were met, and each of us who had visited the office or attended a ‘feedback session’ knows their capacity for bullshitting.

Uber did, however, respond to press requests for comment, claiming that over the summer “couriers using our app took home an average of £9 an hour”. This response was roundly criticised by couriers, who pointed out that these hours only represent logged on time, and take no account of vehicle maintenance, time off for injury or holiday, and no consideration was made for the costs of maintaining vehicles, phones, data contracts, and so on. It was also raised that this ‘average’ hourly earnings did not take into account the unsociable hours we often work, and the uncertainty of going to work not knowing if it will be a £10 an hour day or a £4 an hour day.

We are planning a series of Monday activities going forwards, including social events and film showings for couriers, and more than likely repeats of this weeks actions.

All in all, this was the boldest action so far for the Glasgow branch of the Couriers Network, and we are extremely happy with how it went. In the following days we received wide press coverage, increasing our exposure and couriers confidence in our strategies, and, most importantly, we showed Uber that we are a force to be reckoned with, capable of disrupting service by collectively logging off at short notice during a busy period.

author

Stan Mills

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?