'Everything comes from struggle': An interview with The Paris Autonomous Deliverers’ Collective

inquiry

'Everything comes from struggle': An interview with The Paris Autonomous Deliverers’ Collective

by

Joe Hayns

/

Sept. 19, 2018

‘The street is our factory’

The Collectif des livreurs autonomes de Paris (The Paris Autonomous Deliverers’ Collective, or CLAP) are a group of Paris-based delivery riders - employed by Deliveroo, Uber Eats, and so on - who are together organising across the city.

In August 2017 CLAP members led a series of strikes against Deliveroo’s changing the pay structure from a guaranteed hourly minimum to a fully piece-based system, being exactly the same change that provoked the London Deliveroo rider protests in late 2016. CLAP have since organised workers across the food delivery platforms, bikes and mopeds, with their latest action - a mass deactivation over the weekend of the World Cup final - contributing, they think, to Deliveroo and other platforms suspending their services.

Joe Hayns

Steven, founding member of CLAP

The following interview was conducted in English, whilst travelling across Paris; it was lightly edited for clarity. Thanks to CA for her support before and during the meeting.

How did CLAP start?

We started around February last year, from a gathering of some bikers who wanted to strike against platforms, and do some activism, and not just ideological work.

Six months before that, there was another platform, Foodora, who stopped business without paying bikers. The company went bust, and many bikers weren’t paid. Of the first members of CLAP, many worked for this company. They were saying “we can’t be without protection - they, the platforms, have to protect us”.

How have the larger, longer-established organisations related with riders? Do you work with them?

In CLAP, some of us are in Sud’s (Solidaires Unitaires Démocratiques) Commerce branch, and others are in the CGT (Confédération nationale du travail)

Both of these unions have sections that represent Deliveroo and Uber Eats riders, but they have both found it difficult. They have structures now, after riders had a big fight with them.

The first strike from riders in France was in Bordeaux, in 2016. They asked the CGT for representation, and the CGT said “no, you are a little boss”. The bikers had to strike alone, but after this fight - against the CGT - the union said “OK, you are workers”. After that, Sud did the same, and tried to syndicalise a lot of bikers.

But the structure of trade unions are not adapted for riders, because we don’t have a factory, a place, somewhere to give leaflets, no coffee machines for chatting around - ‘Le rue est notre usine’, ‘the Street is our Factory’, as we say.

But you do physically meet together, as members of CLAP?

I think there is a contradiction in these platforms. We don’t have a workplace, but when we are working, there are some strategic places - between two big restaurants, for example - that, when you work, you know about.

Every biker goes to this place. And at that moment, at this place, we can speak

I’ll ask about tactics in a moment. On the riders - in the UK, it tends to be younger people, with a substantial number of men of colour, and that’ve migrated here. Is something similar true in France? How does migration status relate with this work, do you think?

There are a lot of Bangladeshi riders for Deliveroo and Uber Eats. The platforms try to employ a lot of migrants, because, they think, they will keep quiet, and won’t strike.

Sans papiers need to buy an account from a French guy, because in France, we need to create an enterprise to work lawfully, and you can’t do this if you’re a sans papier. So, they pay for a Deliveroo account from French people. They buy it, and give 50% to the French guy. We are fighting against this.

We say that the guy who is selling his account to an illegal immigrant, for profit, without doing anything, is doing the same shit as a Deliveroo or Uber Eats boss.

During the first wave of Deliveroo and Uber Eats strikes in the UK, over the late summer of 2016, workers protested outside firms’ offices, and also deactivated. Following that, there’s been a legal campaign from the IWGB (Independent Workers Great Britain) union, for the re-classification of riders as workers. And, in late November last year, riders blocked Deliveroos’ Brighton ‘Editions Kitchen’, where restaurants make food exclusively for delivery, which you now have in France, too.

I think then we talk about series of “spontaneous” strikes alongside a legal campaign. What kind of tactics have you used?

Our biggest tactic is to block the restaurants. We all stop working at the same time, and we go to the same place, to the same restaurant, and we ask them to stop the tablet [used to organise deliveries], so there is no profit. If they don’t do what we say, we stay, outside the restaurant, shouting - and when they stop it, OK, we will go to another restaurant. We try to strike like this.

From September, we will have a permanence - somewhere where we will stay, one day a week, where we will help bikers with many things - advice about work, and so on.

In the UK, the strategy of the Independent Workers Great Britain (IWGB) union has been to demand not that riders get more per piece, but to show through the courts that riders are workers - not, as Deliveroo claim, independent contractors - and therefore entitled to certain statutory minimums.

You talked about riders’ status and social security - access to services - in an interview last March with the Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste (NPA), saying that you are in a ‘zone grise’, a grey zone, when it comes to both work-based benefits, as IWGB are addressing, but also access to social services.

Could you speak about how your relationship with the employer relates to accessing social security?

What we want is social protection, dignité - a little money, to live. We want access to social security. If we get that through legal recognition as workers, OK; if it’s through some micro business statute, that’s OK too ..

[At this point in the interview our companion got trapped between a metro car’s doors, taking our attention away from the question, which we didn’t return to. To quote the NPA interview:]

Since we’re not considered workers (salariés), we don’t have to social security. When we’re hurt, all the costs are on us, unless we have private insurance, which between 60-80% of couriers don’t have.

The Macron administration recently proposed a chart social, which appeared to be a suggestion of how platforms might relate with workers. What’s CLAP’s view of it?

It was another bullshit communication from the government of Macron. When we began the World Cup strike, this question of the chart social was put to the Senate, and the Senate said “No”. It wasn’t a victory, it just meant more time. What we say about the chart social is that the platforms and the government are just discussing between themselves, without bikers being involved.

In fact, the chart doesn’t put any obligations on the platforms. They can say what they want: ‘tout passe par la lutte’ - everything comes from struggle.

Cheminots and cheminotes on strike, students occupying faculties - there was a cautious optimism in the UK about the working class in France over the summer, against Macron’s attempting what Thatcher achieved, as another trade unionist, Tiziri Kandi, put it to me earlier this year .

Well, there’s a difference - Thatcher won.

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

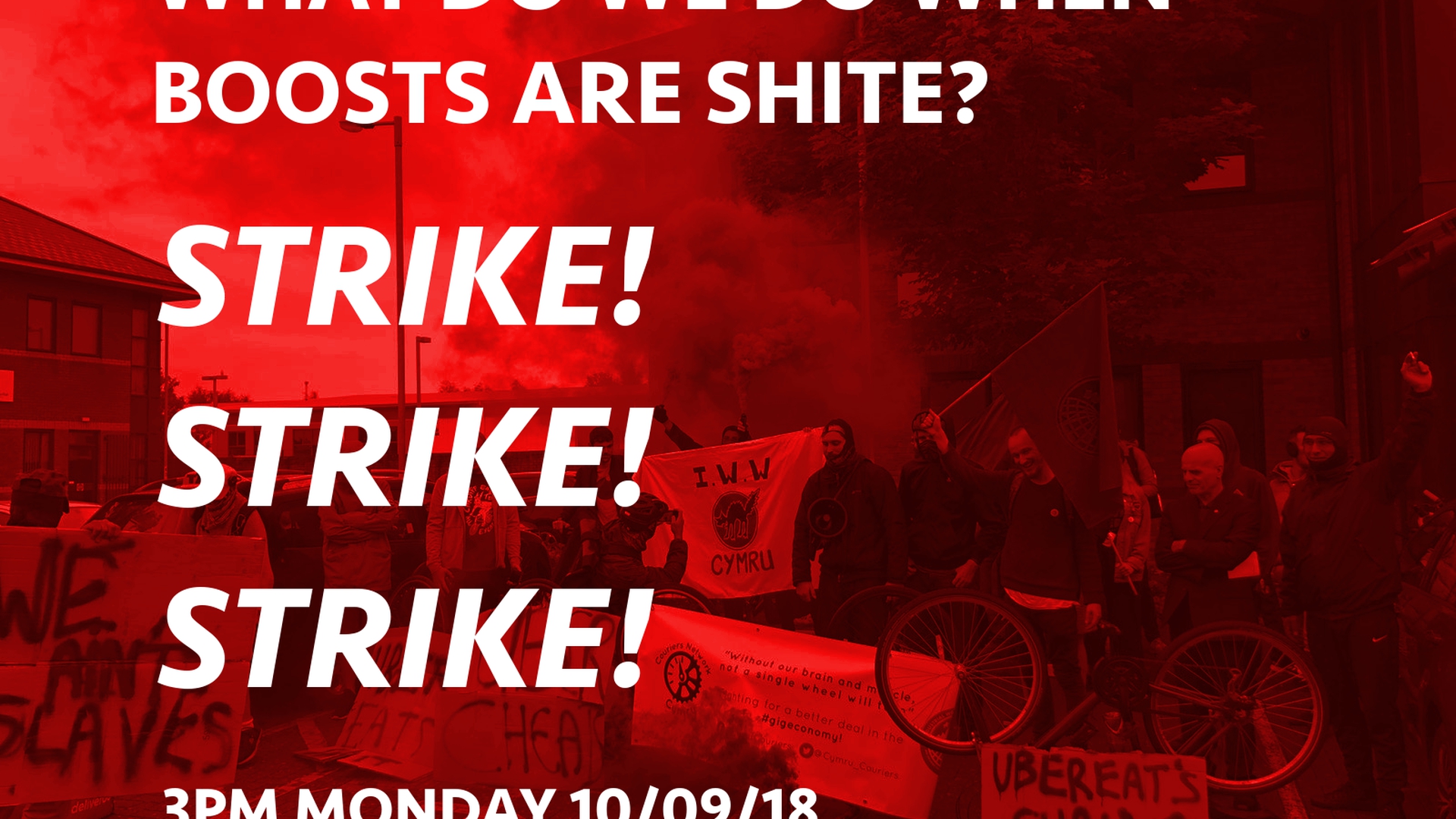

Glasgow Couriers Strike Against Pay Cuts

by

Stan Mills

/

Sept. 18, 2018