The Coming Indigestion

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

September 21, 2023

Featured in Seeds of Struggle: Food in a Time of Crisis (#18)

An introduction to Issue #18

inquiry

The Coming Indigestion

by

Notes from Below

/

Sept. 21, 2023

in

Seeds of Struggle: Food in a Time of Crisis

(#18)

An introduction to Issue #18

The course of events that leads to a revolutionary situation is always unpredictable in advance. In January 1917, Lenin gave a lecture. It was on the 1905 revolution in Russia, and he closed his talk by reflecting on the likelihood of The Great War leading to uprisings across Europe. In the case of Russia, however, he was much more pessimistic: “We of the older generation may not live to see the decisive battles of this coming revolution.” Nine months later, the first proletarian revolution began in Petrograd.2

Whilst the situation outlined above doesn’t seem likely in the short term, neither does a continuation of the status quo. As the overlapping disasters of life in the 21st century continue to intensify, a sense of political normality cultivated during the pre-2008 years isn’t much use for navigating the present. The conditions and tensions our speculation are based upon are real and ongoing. We have argued before that the progression of climate change will be experienced in Britain as a relentless assault by capital, punctuated by bouts of more acute crises. The ruling class of shareholders and managers will attempt to crush real wages in order to protect profits, and rely on an increasingly authoritarian state to control the explosive social consequences. Food is one of the prime factors through which we will experience that assault. The cost of eating will continue to creep upwards, both because of the rising material costs of production as productivity declines in a heating world, and ‘greedflation’ price hikes by powerful profiteering capitalists. The cost of the weekly shop will escalate compared to our wages. Food will become a painful pressure point, around which social tensions will build.

Economists talk about ‘elastic’ and ‘inelastic’ demand. Commodities with elastic demand become less popular as their prices rise: people choose not to consume them because they cost too much. On the other hand, some products have constant demand, regardless of the price. Food is one of these commodities - regardless of the price, we all have to keep buying. It is the inflation of inelastic commodities that will see inflationary pressures leading to social struggles. Fuel has already been the centre of the Gilets Jaunes movement in France in recent years. Housing has equally become a point of contention across the developed capitalist world. Energy, water, internet access, childcare, healthcare - all are in the same category. When we inquire into the production of these commodities, we are discovering fundamental things about the flashpoints of the future. But beyond preparing us for struggles to come, this inquiry also challenges us to think about the reorganisation of production. Whereas some inelastic commodities don’t need to be produced under communist social relations (goodbye, Monarchy-themed biscuit tins) food will always need to be produced, even if we do so in radically different ways.

In this issue, we have inquired into the capitalist production of food. We find a world of food production that is characterised by weird distributions of capital and agency. Many of the workers who have written for this issue are struggling to find a strategy that allows them to organise in their workplaces along basic trade union demands for decent pay and conditions, let alone along more expansive political ones that ask fundamental questions about how our economy is owned and operated.

In A Workers’ Inquiry into Seasonal Agricultural Labour in the UK, Clark McAllister provides a first-hand account of the labour process on a British farm, drawn from a broader covert inquiry into the conditions of work and struggle in the agricultural sector.

In A Workers’ Reflections on the UK Seasonal Worker Visa: Debt and Recruitment an anonymous farm worker gives a first-hand account of the barriers seasonal migrant farmworkers face in accessing work in the UK. It documents how the relationships between the British state’s work visa schemes, recruiters outside of the UK, and farms in the UK combine to extract value from workers and lock them into situations comparable to debt bondage.

In Struggle of Agricultural Workers in Italy, Francesco Piobbichi analyses the struggles of seasonal farm workers in Southern Italy, showing that the regulation of migrant labour is central to the control of food monopolies.

In A History of Farmworkers’ Struggles, Dante Philp and Matthew trace an outline of the neglected history of farmworkers’ struggles, from the early 1800s up to the present day.

In There and Back Again, a Yoghurt’s Holiday, Callum Cant, George Briley, and Matthew draw on first hand worker interviews and reviews of industry reports to sketch out how food is transported from factories to distribution centres, revealing the workers’ power that exists in the process and the areas in which we need to inquire further.

In We will need to eat during the revolution too!, Notes from Below interview Angry Workers, a small political collective who spent over six years organising in food manufacturing and logistics companies in West London.

In Work Well for Less, an anonymous supermarket worker gives their perspective on the role of unions and struggle in supermarkets, the introduction of technology in the workplace, and the increasing violence and shoplifting they experience on the shopfloor.

In Food Price Hikes, Social Composition and Auto-Reduction, Jamila Squire and Seth Wheeler outline the history of social struggles over food, and consider what a militant, mass campaign over the right to food could look like in our current cost-of-living crisis.

In Cooking Behind Closed Doors, an anonymous worker offers a sobering glimpse behind the curtain of on-demand food production for delivery apps in a “dark kitchen”.

In London’s Food Scene: Flexibility, Diversity, Precarity, London chef, Eric Jeffers, surveys shifts in the organisation and experience of restaurant work since Covid.

In The Development and Trajectory of the French Ecological Movement, Sara Marano and FX Hutteau trace how the unique political conditions in France have facilitated the emergence of a novel, and highly antagonistic, network of ecological campaigns over the last decade.

Finally, in Confronting Eco-Apartheid, Kai Heron reiterates the uneven distribution of the effects of climate change, how our global economic system is already predicated on a system of ecological and labour apartheid, and how ecological justice requires going beyond calls for green jobs in the imperial core.

The roots of the problem

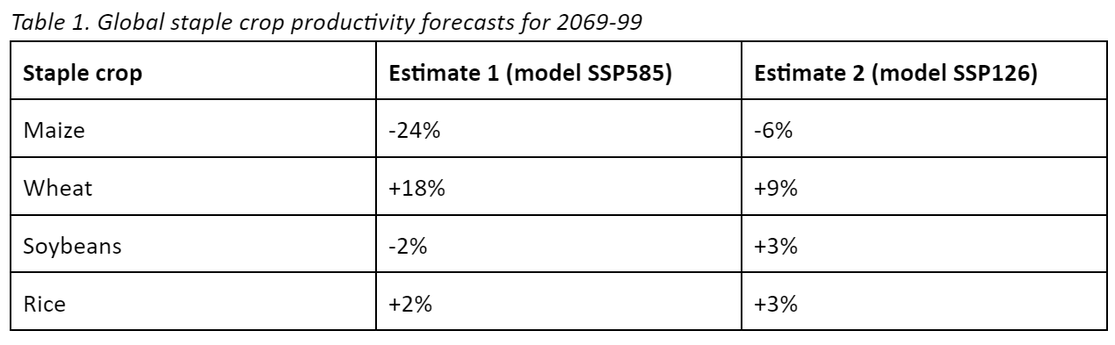

As climate change continues to accelerate, the ability of global agricultural productivity to stay ahead of the demand caused by population growth will continue to be threatened. There is no indisputable model of how major crops will respond to temperature increases because of the incredible complexity involved in modelling future climatic changes. One study suggests that major ‘breadbasket’ food producing areas will start to see significant changes in agricultural productivity by 2040. It then uses two models with different assumptions to make a range of predictions about how global crop production will be impacted by temperature changes.3

However, another study estimates that global wheat production will fall by 6% for every degree of warming. Therefore, rather than positive rises in wheat yields, they predict we’re more likely to see a 12% to 24% decrease within the same time period.4 So two widely cited studies in top journals suggest completely contrasting futures: one in which wheat yields rise by as much as 18%, and another in which they fall by as much as 24%. These are big differences - therefore it seems stupid to make any hard and fast predictions about the exact trend of crop yields in the future.

However, we can compare the most optimistic yield estimates for staple crops with the potential for population growth. The UN estimates the world population as 7.9 billion in 2021, and projects that it will grow to 10.4 billion in 2099. That’s a 31% increase. Even assuming ongoing technological changes boost productivity, any kind of decrease in yields for key staple crops in tropical areas would likely see a very significant increase in food prices. This fits with the assumptions of some food economists, who project a 1–29% average cereal price increase by 2050 compared to a ‘no climate change’ scenario.5

This upwards price trend will not just be a smooth line, however. One of the characteristic features of the ecological crisis is extreme weather events - and these will lead to supply interruptions and rapid price increases in the global food market. In 2010, for example, global food prices rose by 30% off the back of extreme droughts in Russia and Eastern Europe. The economics of these shocks are complicated, but some analysis indicates that 25-30% of inflation in Europe over the period 2009-2015 was caused by food price rises,6 and that rich countries that import a lot of their food are particularly exposed to negative GDP growth as a result of extreme weather events that produce surprise shortages.7

We can assume a gradual upwards pressure on prices then, which may be more or less severe, depending on who’s right about staple crop yields. Alongside this upwards trend we’ll see occasional sharp shocks interrupt supply and lead to rapid price increases in the global food market. What does that kind of world look like?

In the developing capitalist economies, this will probably mean import prices will go beyond the reach of ordinary people, resulting in famines. If domestic production declines at the same time as prices spike in the international market, then the stage is set for extreme famines. This trend is likely to be particularly exaggerated because projected global population growth will be concentrated in the developing world, and as tropical areas will be subject to particularly strong downwards pressures on agricultural productivity. This is the future capitalism has created for the global majority. The upheaval resulting from these situations will be colossal.

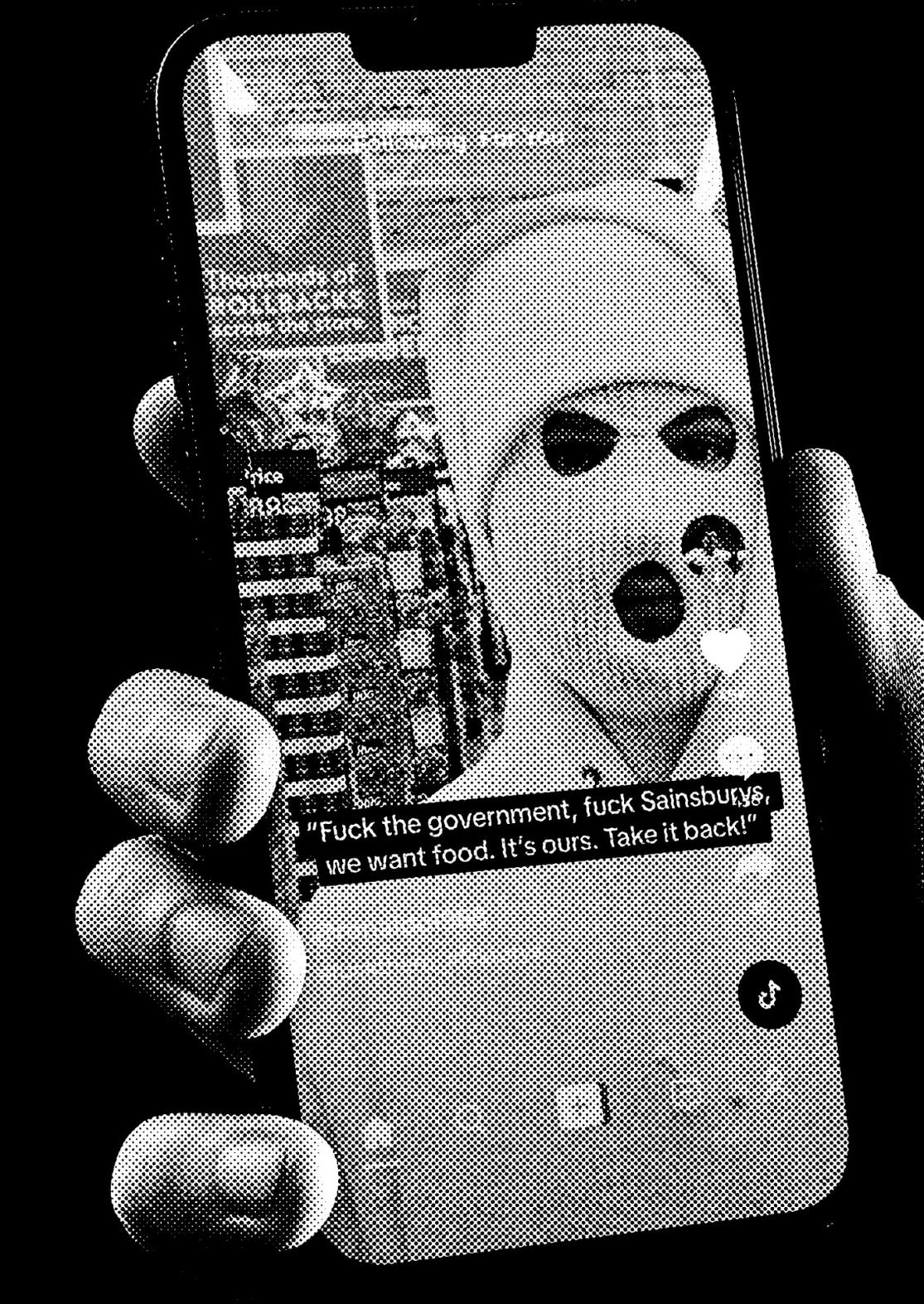

In the advanced capitalist economies, it will be lower. In the context of a falling labour share of income and declining real wages, food price inflation will be one of the major contributing factors accelerating the immiseration of the popular classes. The proportion of money an average household spends on food will climb, pushing other ‘elastic’ commodities out of reach. Occasional supply shocks will leave shelves empty, and it’s hard to predict the duration or character of these temporary crises, but even if our food system is resilient enough to cope with them, the general tendency for food to cost more seems unavoidable. All of this points to an intensifying pattern of conflict between capital and labour, characterised by wage struggles at the point of production, as well as disputes over the prices of essential commodities in the sphere of consumption.

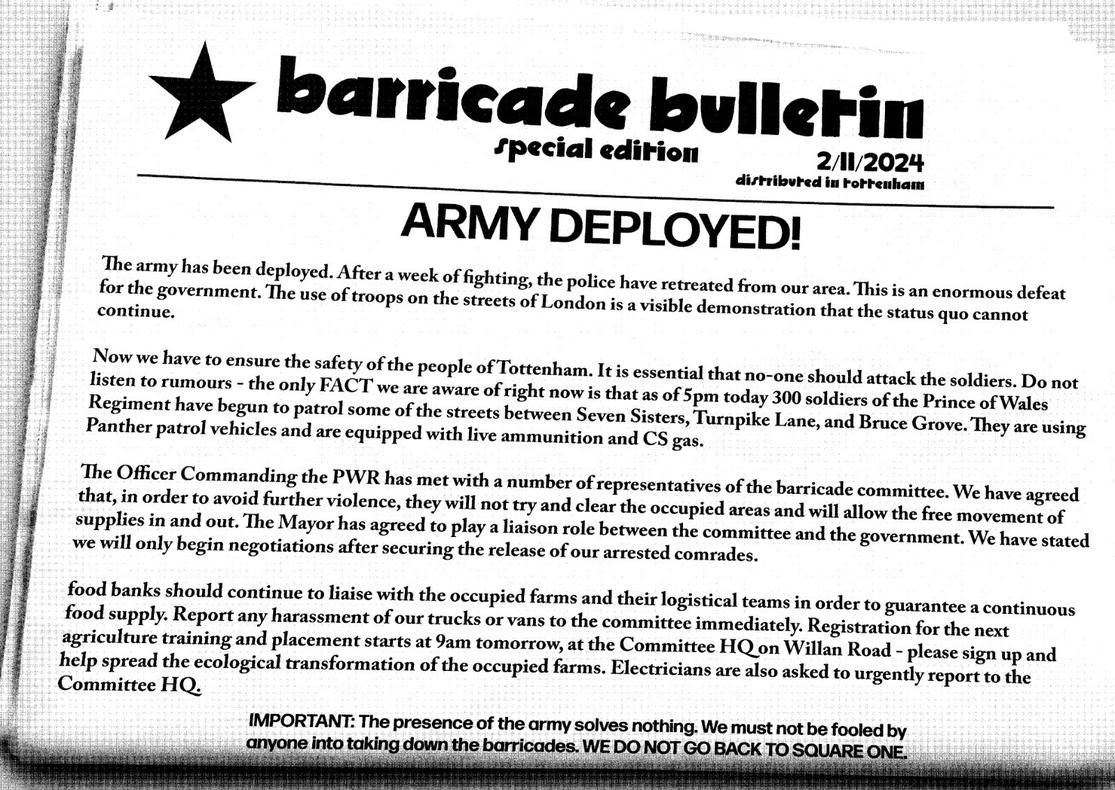

The concentration of resources in the hands of the ruling class that began to accelerate with the neoliberal turn of the 1980s is continuing to accelerate. British society is on the verge of missing an adaptive window, during which the working class could have been integrated into a new economic and political settlement through reforms akin to the Reform Act of 1832 that extended the vote to a wider selection of men, or the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 that lowered the price of bread. But no new deal has been put on the table. The ruling class has taken every wave of social disruption, from the crisis of 2008 to the coronavirus pandemic, as a chance to enrich itself and immiserate the majority. This continual smashing of the working class has produced vast suffering, but as of yet limited social conflict. But with climate change accelerating the immiseration of the popular classes, with work intensified and stripped of its redeeming qualities, and society lacking any of the spare capacity to absorb shocks, it seems like we are now set on a course that can only lead to that delayed conflict bubbling up to the surface sooner or later. Unless, of course, the state can do something to diffuse these developing antagonisms.

Running out of room for manoeuvre

In the last four years there have been two crisis situations that the British state has handled through exceptional measures that squashed the free market under the heel of government intervention. The first was furlough, with the state stepping up to become an employer of last resort for millions during the Covid pandemic. The Energy Price Guarantee was the second, as Truss committed to spending approximately £37 billion to keep energy prices down. Both of these adaptations were surprising, insofar as they indicated that the government’s fear of sparking a social crisis was sufficiently advanced that they were willing to junk their ideological commitments and existing priorities to plug the gap. Both of those huge concessions bought social peace - but at a very high cost. The UK’s debt to GDP ratio went over 100% for the first time since 1961 in June.

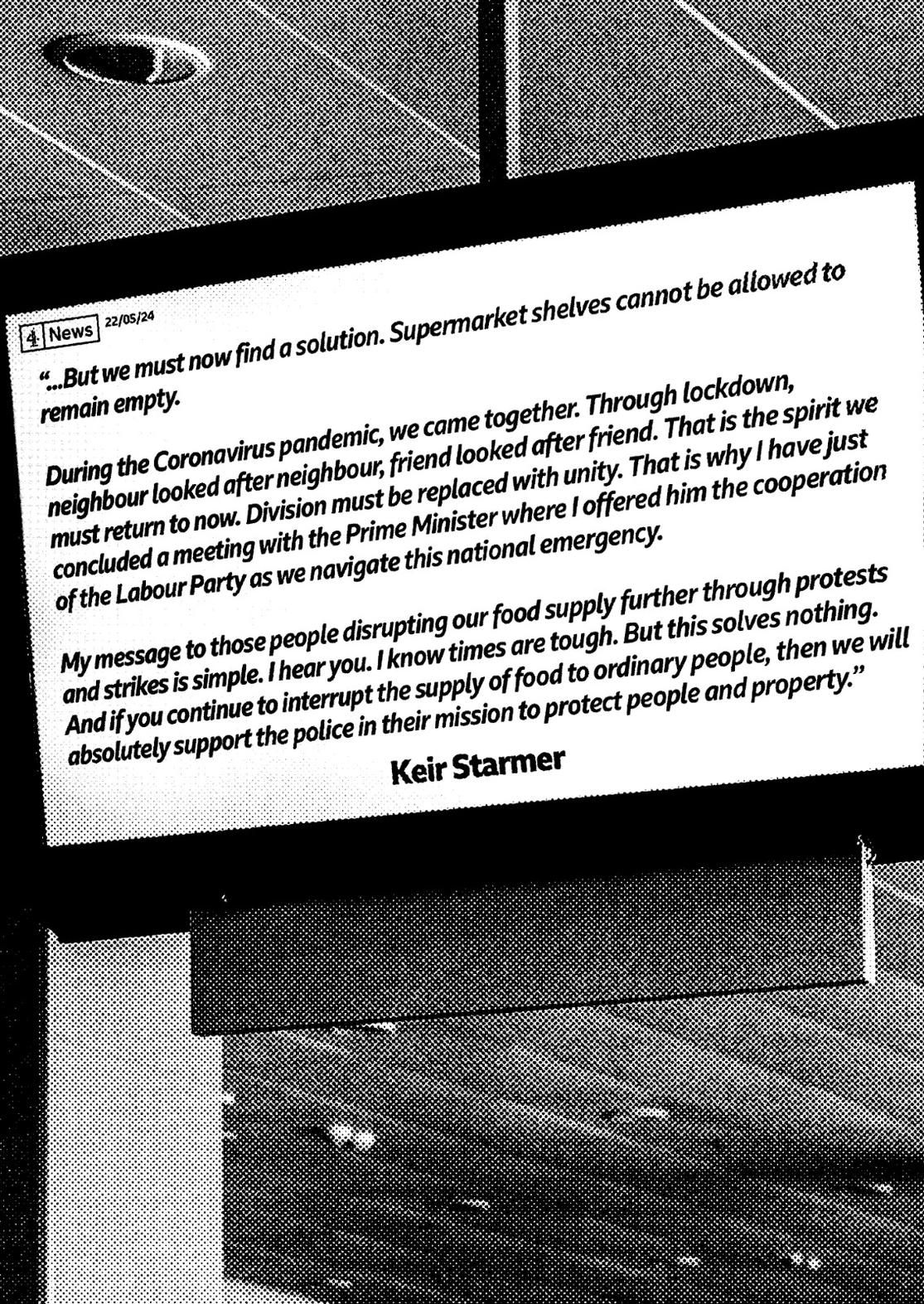

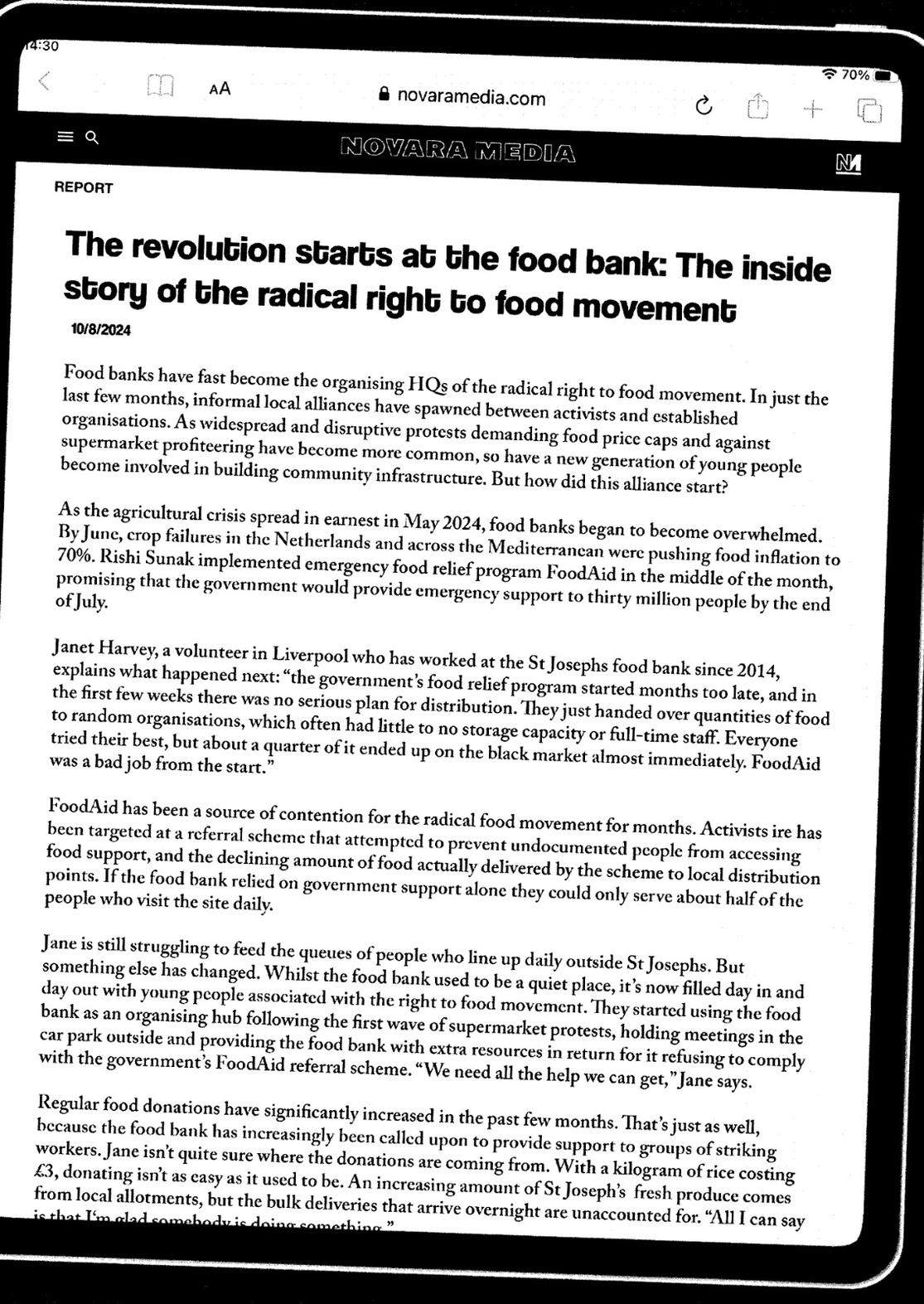

But we have started to see some impetus towards a third such compromise. In late May, the Sunday Telegraph (favoured paper of disgruntled Tory backbenchers) splashed the news that Sunak was considering asking the big supermarkets to cap prices on essential goods, thereby forgoing some of their billions in profits. Industry representatives squealed, claiming that “1970s-style price controls” wouldn’t do a thing. Starmer’s Labour took the supermarket’s side, and esteemed Tory MPs moaned about market intervention. Only Labour’s miniscule left wing and some socially conservative Tories associated with the Common Sense group of MPs welcomed the idea. By mid-June, the Telegraph was again the first to report on a new development: the scheme was dead in the water.

This sequence is exemplary of the increasingly limited space available for the state to develop policies that address the crises associated with the collapsing value of real wages. Subsidising the costs of supermarkets directly has presumably been rendered unviable in the eyes of the Tories by the level of public indebtedness (particularly given the rising costs of government borrowing), whilst opposition from the supermarkets, determined to defend their profit margins, rendered a voluntary scheme unviable. The only other option would have been to legislate to limit costs, but there was very limited support from the tory backbenches for doing so. So, if the state won’t intervene to reduce food costs at the point of consumption, what offers could be on the table?

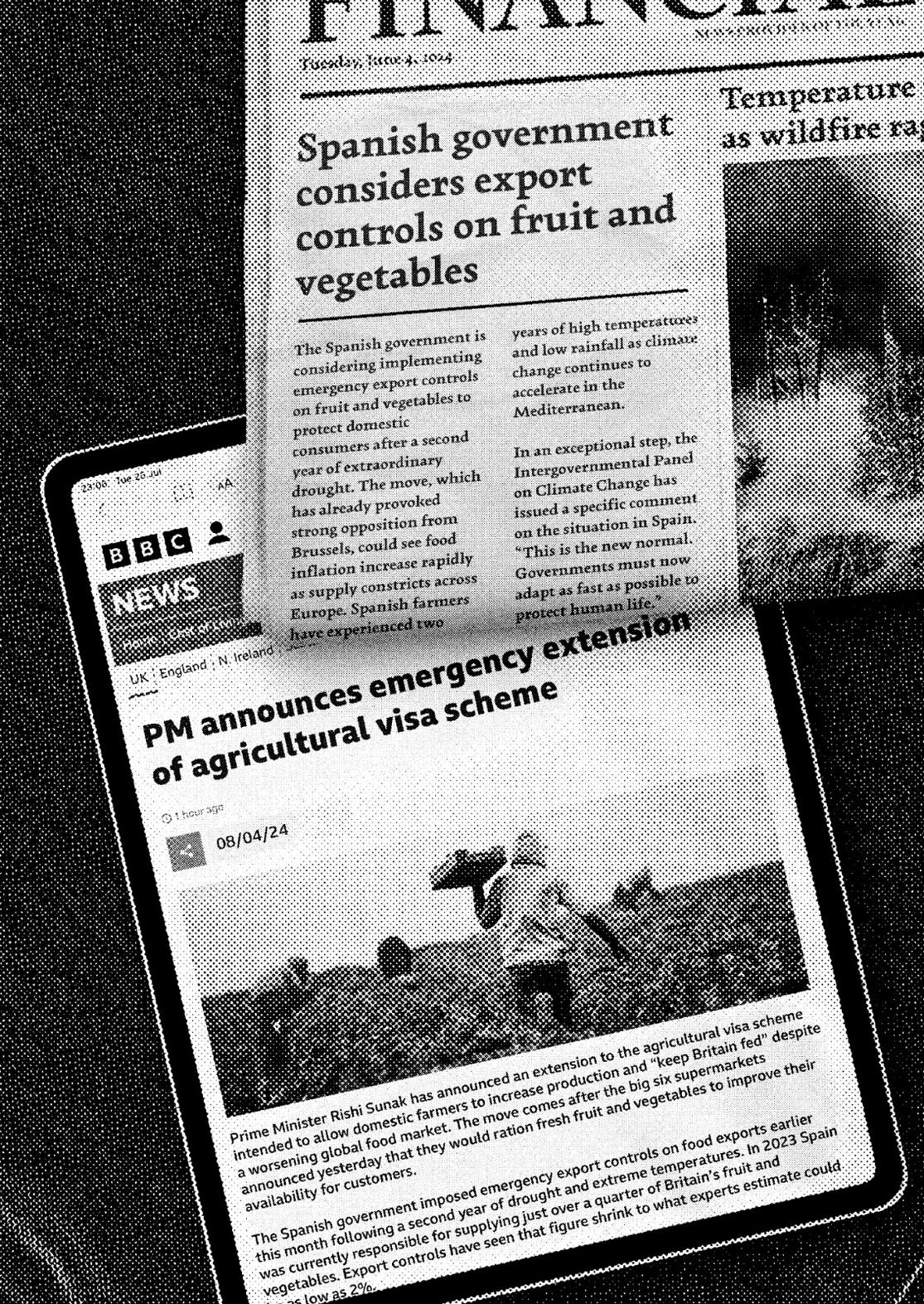

Assuming that the wonks of Whitehall are looking at the same research as us, there is one obvious approach: take steps to guarantee national food security and reduce Britain’s exposure to international food markets by maximising the productivity of domestic farming. There are a number of ways to do this, but the most obvious limiting factor right now is the availability of cheap labour. Tight labour markets mean that agricultural capital is operating at less than full productivity. Since anti-immigration posturing will no doubt be the decisive factor in the next election, it seems unlikely that the importation of cheap agricultural labour will be front and centre of any future government’s agenda.

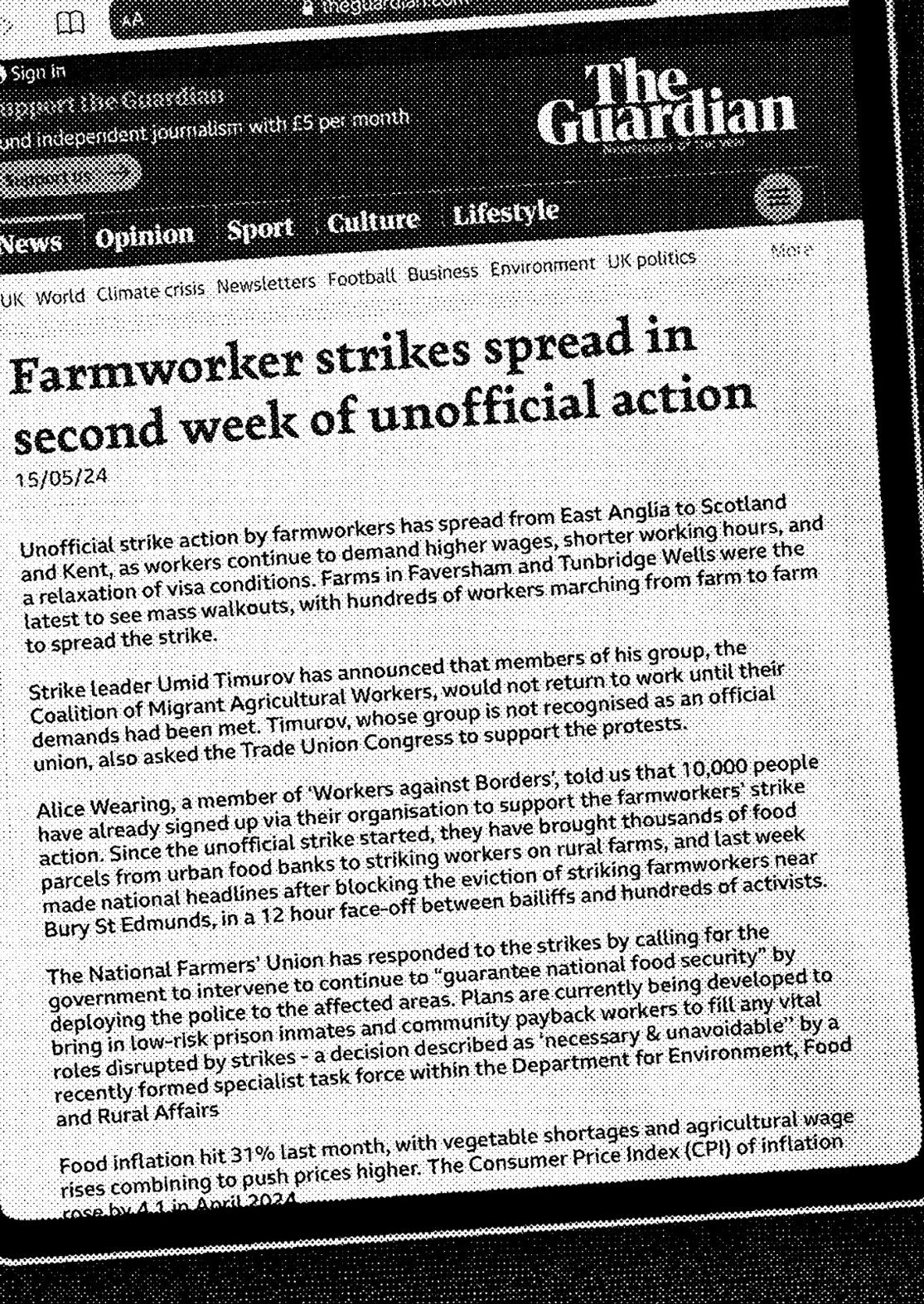

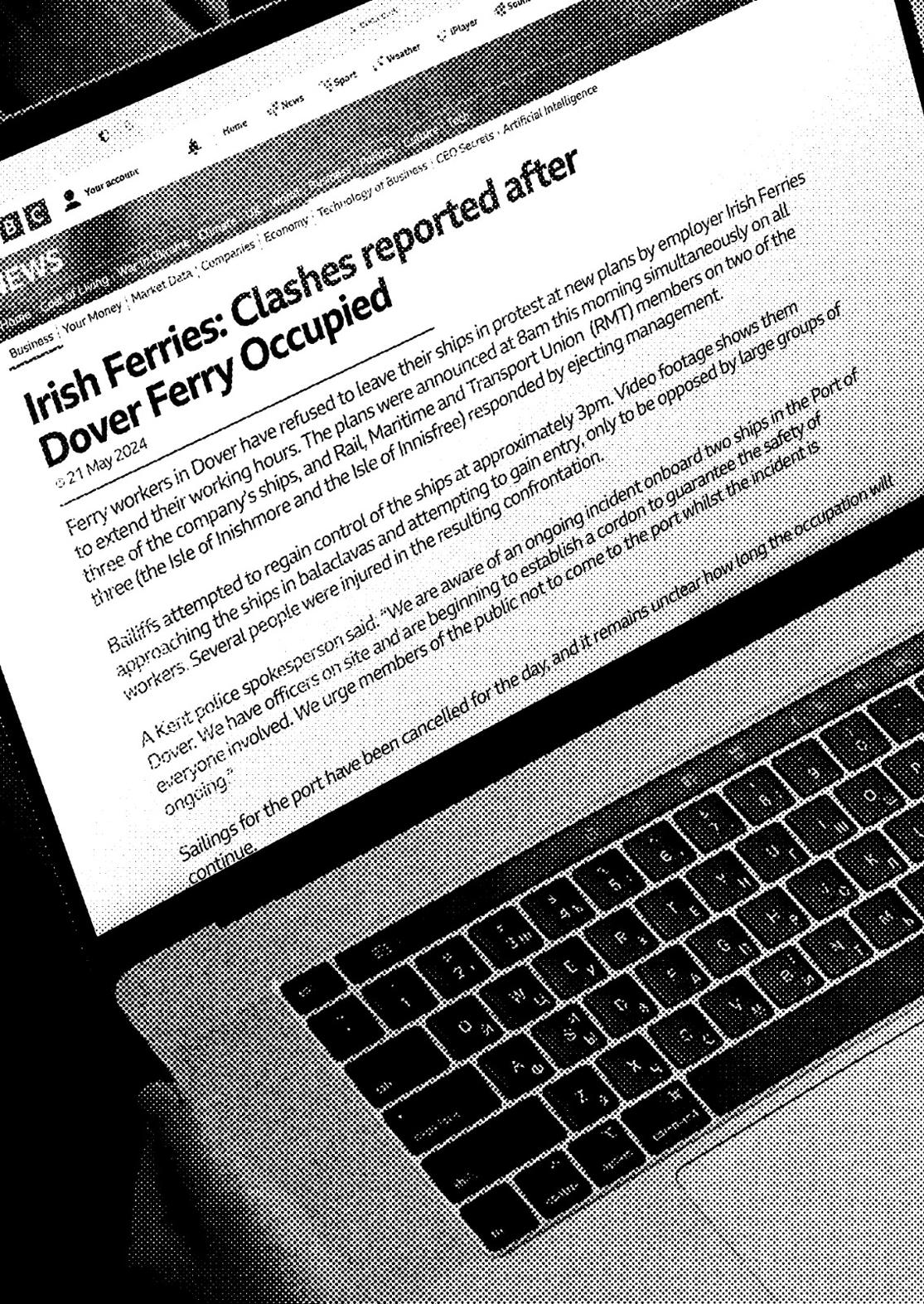

But behind the dystopian spectacles of border militarisation, the issuing of seasonal work visas in the UK has been growing: in 2023, up to 55,000 visas could be issued, up from just 2,500 in 2019. This contradiction is playing itself out most sharply in the experiences of migrant seasonal workers. Testimonies in the recent Horticultural Sector Committee Inquiry revealed the harrowing realities of agricultural work in contemporary Britain. “We were not treated as humans, we were treated as chattel”, commented one former seasonal worker in the inquiry. This is clearly not an anomalous scandal but spells the direction of travel of late authoritarianism in dealing with global food insecurity. Borders have become a crucial instrument for disciplining workers, staving-off productivity drops and cooling prices by enabling states to manage an apartheid labour system that brutally disciplines workers. Whether this growing subproletariat will emerge as an organised political agent, as has been the case in Southern Europe, remains an open question.

The other option is for the state to intervene to seize resources for the agri-food sector. The British polity has concluded that the stress test of the pandemic showed the resilience of UK food supply chains. This consensus has driven an appetite to “further build the UK’s resilience to future crises and shocks.”8 What this means in terms of the government’s food strategy is an emphasis on controlling and streamlining the allocation of key inputs (fertilisers, cleaning agents, additives, refrigerants and the all important supply of CO2) to agri-business. This in turn has propelled the standardisation of secured freight capacity and the attendant transformations in the haulage industry. It has also led to the promotion of land use changes which could further controversial intensive farming methods such as mega basins and concentrated animal feeding operations.

What’s clear from contributions in this issue, in whatever direction these interventionist measures move, the terrain of future ecological labour struggles must follow.

What is to be done?

In June, the big bourgeoisie assembled at the Savoy hotel. They were there for a wealth management conference - but in some panels, they were given an unusual message. There was, one speaker said, a “real risk of actual insurrection” if something wasn’t done to combat wealth inequality and insulate ordinary people from the impact of food and energy price hikes in the years to come. We know that the apocalypse fantasies of the billionaire class are already very advanced. Tech futurists have been building themselves bunkers in New Zealand and Alaska for years. Now it seems the alarm bells are ringing in ever wider layers of the elite.

We are approaching a moment where communists could make a significant intervention into British politics. But despite a resurgence in industrial action, we have yet to see significant progress in the organisation and power of our movement. We have repeatedly urged people to “join a trade union” and “organise where you are,” but the list of resulting successes is very small. What if we’ve been doing it wrong? Instead of organising where we are, maybe we should be going where there is potential for worker-organisation to have wider social importance. Going beyond covert academic inquiries towards a mass political project organising outside and inside these key industries.

Agitation, as a political activity, aims to fuse economic and political struggles by generalising specific conflicts into more general class ones. Agitational interventions are effective when the production process has general social importance. Working-class struggles in food production are uniquely well placed as there is an obvious social interest in the products of this sector. Food is the commodity upon which all of human reproduction is reliant. Climate change and ecological struggles - one of the greatest societal challenges of our moment - are also deeply connected to how we produce and distribute food.

Those who control how food is produced and distributed also hold major influence over how we relate to one another, and ultimately, how society functions. Yet many of the areas identified in this issue as key to the production of food, and therefore key to unlocking this transformative potential, are areas where the revolutionary left has a minimal presence. Shifting our agitational interventions towards these areas could be key to building a communist movement capable of doing more than simply reforming capitalist society, but rather reshaping it into one based upon free association and human need. The social composition of the class is central in relation to food when we think about society in general - but what is a question of consumption for most people is a question of production for those people that work in the industry.

The onus is therefore upon us, as militants, to intervene in those conditions, to escalate the conflicts that emerge from specific workplace ones to wider class struggles, and understand how these opportunities can be used to reshape society. Inquiry and intervention into key sectors, such as the food production, isn’t a strategy in and of itself - but rather a starting point from which a communist strategy for the wider transformation of society can emerge, by the working-class, for the working-class.

** - The Editors, June 2023**

-

Based on a bulletin distributed in Free Derry on August 14th, 1969 ↩

-

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich (1917) ‘Lecture on the 1905 Revolution’, Marxists.org. ↩

-

Jägermeyr, Jonas, Christoph Müller, Alex C. Ruane, Joshua Elliott, Juraj Balkovic, Oscar Castillo, Babacar Faye, et al. (1 November 2021) ‘Climate Impacts on Global Agriculture Emerge Earlier in New Generation of Climate and Crop Models’, Nature Food. Vol. 2:11, pp. 873–85. ↩

-

Asseng, S., F. Ewert, P. Martre, R. P. Rötter, D. B. Lobell, D. Cammarano, B. A. Kimball, et al. (February 2015) ‘Rising Temperatures Reduce Global Wheat Production’, Nature Climate Change. Vol. 5, pp. 143–47. ↩

-

Peersman, Gert (2018) ‘International Food Commodity Prices and Missing (Dis)Inflation in the Euro Area’. National Bank of Belgium. ↩

-

Ibidem (Ibid.) ↩

-

De Winne, Jasmien, and Peersman, Gert (8 August 2021) ‘The Adverse Consequences of Global Harvest and Weather Disruptions on Economic Activity’, Nature Climate Change. Vol 11:8, pp. 665–72. ↩

-

Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs (13 June 2022) Government Food Strategy. ↩

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Welcome to the future: this strike wave is just the start

by

Notes from Below

/

April 28, 2023