The Working Man’s Eye

by

Edwin Hoernle

October 11, 2024

Featured in Photos from Below (Book)

Edwin Hoenle’s classic article on photography as a working-class weapon, originally published from 1930.

theory

The Working Man’s Eye

by

Edwin Hoernle

/

Oct. 11, 2024

in

Photos from Below

(Book)

Edwin Hoenle’s classic article on photography as a working-class weapon, originally published from 1930.

‘Another Bolshevik exaggeration!’ I hear the reader exclaim. ‘Surely the eye is essentially the same organ in all human beings, and only illness or injury can alter its structures and functions. Of course it varies in different animal species - spiders, bees, snakes, cats, elephants - but as far as human beings are concerned we cannot speak of workers having one sort of eye and industrialists, ministers, bankers and lawyers having another. Marxists and Leninists should really keep their feet on the ground a bit more!’

Not so fast, my dear fellow-photographer! Even your example of the industrialist, minister, or bankers shows you to be wrong. If a German factory-owner goes to America, what do you think he sees? The Ford works are Detroit, the Chicago slaughter-houses, Standard Oil derricks, the White House, Fifth Avenue; but do you think his eye, the eye of a keen German businessman gorged with profits and eager for more - do you think he sees the six million starving unemployed, the human wrecks of the Ford works who are not yet forty years old, the tiny anemic children worked to death at seven years of age in the textile and canned goods factories of the most democratic and Christian country, the material and spiritual misery in the black quarters of the notorious lynch-state of Texas, or the blood thirsty brutalities perpetrated on striking workers by the bought, bribed police force in the streets and factories?

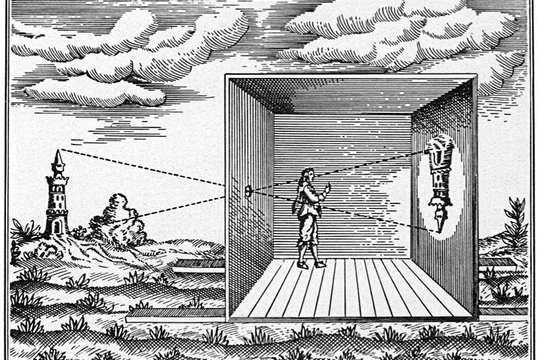

And if he should come across them once in a way - for he cannot always be blind to the seamy side of American ‘freedom’ and ‘prosperity for ever’ - he still doesn’t actually see them because there is a block between his retina and his brain: the pictures taken by his ‘natural’ camera, the one in his head, are not developed and do not reach his consciousness. Or, if by chance they should ever reach the mind of this worthy business man, absorbed in his calculations of profits and high living, they are neither clear-cut nor properly lit - they remain minor exceptions, small shadows in the picture-collection of his brain and his camera, if he has one or the other about him.

What is essential is psychological vision, the liaison between the physical retina and the picture that arises in the mind’s eye. How little the average person is trained to perceive facts is something we can observe any day in ourselves or our neighbors. Can we estimate distances correctly? The word ‘estimate’ itself shows that we are not certain. Five minutes after looking at a house-front, can we remember what its features were? We may take the same city walk every day, but how many of us notice what a splendid theme that wretched little newspaper seller would be for our proletarian camera, or what an insolent criminal-looking type that member of the Hitler Youth is whom we pass regularly in the street, and who perhaps will one day shoot down one of our best friends under the benevolent eye of the democratic police? One needs a professional eye to pick up at once certain details of landscape or machinery, the clothing or habits of other people; and you need the eye of a certain class in order to perceive the signs of prevailing social conditions in the internal and external life of our fellow-beings, in the structures and appearance of homes and factories, their internal organization and the general picture of life in the streets, or even the shape and size of fields and meadows and the crops grown on them.

What is more, this ‘proletarian eye’ must be trained. Millions still lack it altogether, and others only have it imperfectly. Only a very few have the practice and discipline to exercise their class vision at all times and places, on holiday, at weekends and on journeys, at leisure as well as at work. The rule for the working-class camera-man should be: No camera without a proletarian eye behind it!

But here too the proletarian photographer must learn not to stop half-way. We are not Philistines, whether it is a matter of culture or the revolution. We take pleasure in the sight of a pretty girl, in real life or in photography, in contemplating mountains or the sea or the peaceful charm of a meadowed valley. Why not?—but this is not the deciding factor. A handsome face, an imposing tree, a lizard sunning itself on a rock—naturally these too are proper subjects for a proletarian camera; but they are not the subjects that distinguish us from the cultivated bourgeois who tomorrow, perhaps, will sentence our fellow-workers to prison or lead a gang of Nazi thugs against us, and whose fine education and first-class camera are paid for by our sweat and our children’s tuberculosis.

The workers’ world is invisible to the bourgeoisie, and unfortunately to most proletarians also. If the bourgeoisie depicts proletarians and their world of suffering, it is only to provide a contrast, a dark background to set off the glories of bourgeois ‘culture’, ‘humanity’, ‘arts and sciences’ and so forth, so that sensitive folk can enjoy a feeling of sympathy and ‘compassion’ or else take pride in the consciousness of their own superiority. Our photographers must tear down this facade. We must proclaim proletarian reality in all its disgusting ugliness, with its indictment of society and its demand for revenge. We will have no veils, no retouching, no aestheticism; we must present things as they are, in a hard, merciless light. We must take photographs wherever proletarian life is at its hardest and the bourgeoisie at its most corrupt; and we shall increase the fighting power of our class in so far as our pictures show class consciousness, mass consciousness, discipline, solidarity, a spirit of aggression and revenge. Photography is a weapon; so is technology, so is art! Our world-view is militant Marxism, not mere academic wisdom. And we worker photographers have an important sector of the front to hold: we are the eye of the working class, and it is we who must teach our fellow-workers how to see

Featured in Photos from Below (Book)

author

Edwin Hoernle

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Institution of Autonomy: The Worker Photography Movement

by

Steve Edwards

/

Oct. 11, 2024