Perks of the Job

by

Scott Surette (@scottsurette)

March 30, 2018

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

Are tech industry perks a generous offering, or something else entirely?

inquiry

Perks of the Job

by

Scott Surette

/

March 30, 2018

in

Technology and The Worker

(#2)

Are tech industry perks a generous offering, or something else entirely?

Roll out of bed at 9:30, head into the office on the subway using a company-funded transit card. Check email after grabbing a latte from the in-office barista. Play a couple rounds of table tennis after a catered lunch. Head home late after a round of drinks from the office kegerator. It sounds like a dream job, and it’s the reality for many software engineers in major cities around the US. Amazon employees now even have access to an indoor rainforest.

Given all of these perks, it’s no wonder that software developers are often more than happy to put in long hours at the office, and don’t think of themselves as members of the working class. How could they be, when they’re playing table tennis with a beer in hand while blue-collar workers are performing manual labor?

Herein lies the problem with the mainstream American understanding of class. If you have catered lunches, you’re not like the other workers. And if you’re not like the other workers, you certainly don’t organize alongside other workers.

It’s true, tech workers aren’t the most exploited workers, but a Marxist class analysis tells us that they are among the working class. Within capitalism, there are only two sides to the struggle: capital and labor. Despite being treated fairly well, tech workers—software developers, designers, analysts, testers—are the ones who generate value for bosses. Office perks, then, are a way for bosses to extract additional value from workers. Not only do these perks entice employees to work longer hours, they prevent employees from thinking of themselves as workers altogether. Because workers create all value, these perks are paid for by the labor of the workers, though they’re often presented as a gift by bosses who want to be seen as fun and caring.

One of the more insidious forms that these perks take on is that of “unlimited vacation.” This one sounds great, even too good to be true for those outside the tech industry. The reality is that in practice, unlimited vacation often is too good to be true. Tech companies—startups especially—tend to be in constant crunch mode. Because of the constant crunch, it’s rarely feasible to take a long vacation; even when it is feasible, workers feel guilty doing so. In contrast, when I have worked for companies with an allotted number of vacation days, everyone made damn sure to use every single one.

To deal with employees not using their unlimited vacation time, one company came up with “paid paid vacation,” i.e. paying employees a bonus when they take a vacation. This sounds great, but it reinforces the fact that bosses keep most of the value we workers generate for themselves. If companies have an extra $7,500 available any time anyone takes a vacation, they have more than enough to simply give everyone raises.

Not only that, but vacation is often used as a tool to pacify workers who are disinterested in their work. Even if work is unfulfilling, we always have vacations to look forward to. When examined in this light, it becomes clear that vacations are less of a “perk,” and more simply part of the cost of the reproduction of labor. Capitalism rarely offers us meaningful and fulfilling work, so employers rely on vacations to make us temporarily ignore that fact. We do deserve unlimited vacation, as well as worker-controlled workplaces so that we don’t feel guilty for taking them. But we also deserve work that enriches us, so that we don’t so frequently need the reprieve promised by vacation.

All of that said, I like beer and table tennis and vacation. The goal, then, is not to rid offices of these perks. It’s to remind us that despite these perks, tech workers are still workers. Our interests lie with the interests of labor, not capital. When we organize alongside other workers, we can win better conditions not only within our industry, but across all industries, where workers may be more exploited than we are. As Hamilton Nolan writes for Gawker, the solution is for tech workers to unionize:

The most meaningful way for them to take action against the inexorable rise of inequality that is benefiting them is to stand up and declare that they are on the side of labor, rather than on the side of capital—to declare that they are workers who are on the side of all of the other workers, from shuttle drivers to gardeners to janitors to security guards, who make these tech companies function. The way for them to do that is to unionize.

Despite unionization in the US dipping to an all-time low of 10.7% of the overall workforce, the number of professional unions is actually steadily on the rise. Organizations like the Tech Workers Coalition are springing up across the country, with the goal of building worker power through activism and education. Wouldn’t it be nice if the Seattle Spheres were open to all workers, instead of only Amazon employees? Jeff Bezos has not only priced residents out of downtown Seattle, but is now monopolizing green spaces that would benefit everyone.

Standing in our way is the seemingly widely held belief that tech is a “meritocracy.” After all, the internet was built on the idea that information should be free. All of the tools to become a programmer are available to anyone with a computer and a network connection. This belief that tech should be free of gatekeepers is what drives the resistance to unionization, as Llewellyn Hinkes-Jones writes for The Atlantic:

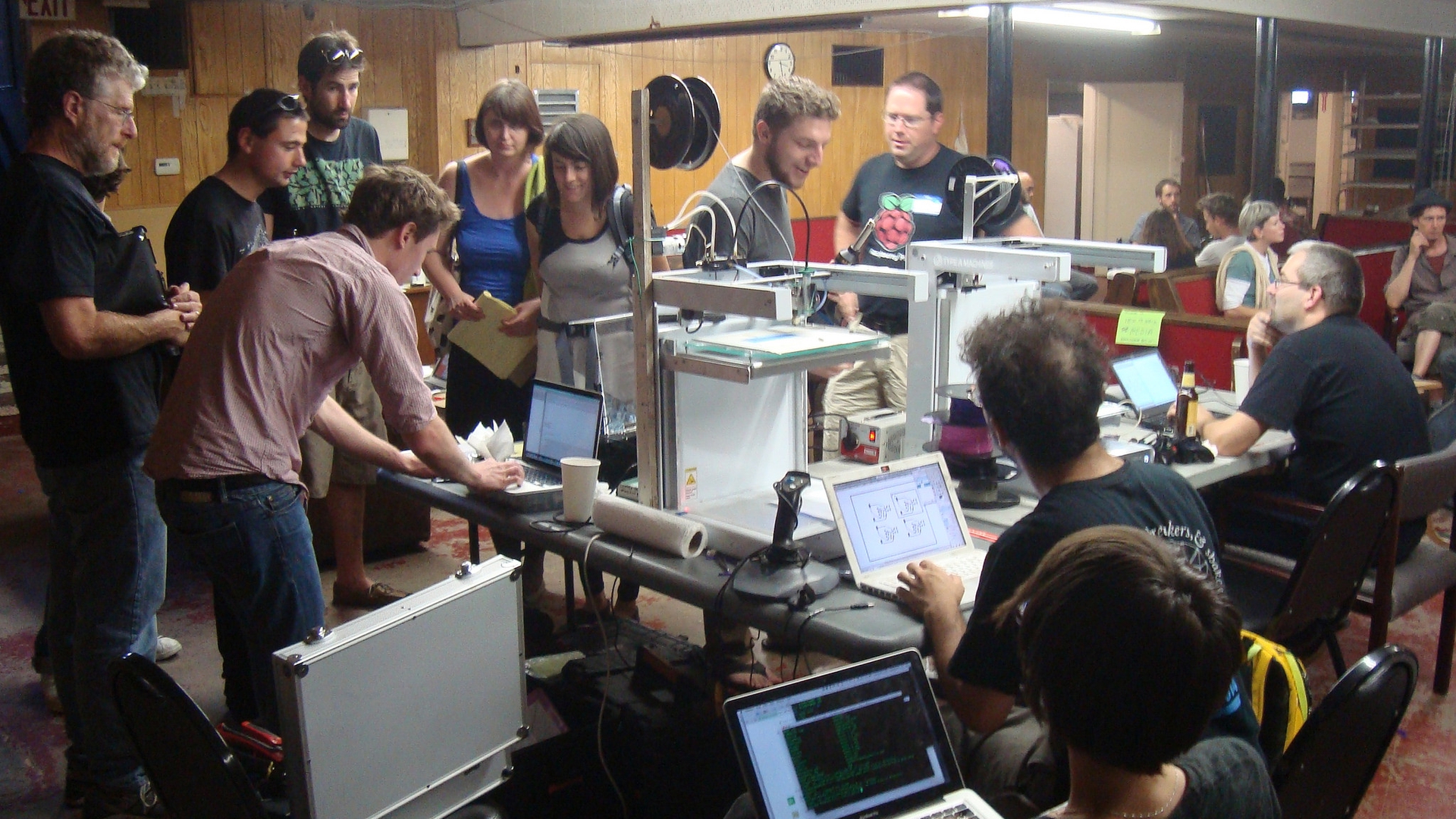

Unions are often seen as emblematic of the bureaucracies of the past. The idea that some complex process could stand in the way of independent accomplishment is anathema to the fundamentals of the libertarian, self-made, DIY, hacker culture.

Of course, the tech industry is not really a “meritocracy.” It’s subject to the same gatekeepers that exist everywhere else in capitalism. Instead of prioritizing the work that is most enriching or that would benefit the most people, we’re forced into the work that is most profitable, everything else be damned. Wendy Liu detailed her own story in the last issue of Notes From Below:

Although we had originally envisioned ourselves as data science startup, it soon became clear that the only profitable avenue was to become an advertising technology startup, selling consumer data to help companies market their products more efficiently. We went to marketing technology conferences in which we forced ourselves to network with people we despised, people in shiny suits and branded lanyards talking about CAC and LTV and NDAs. Our days became a monotonous blend of 3-letter acronyms and sales decks and meetings with people who didn’t want to be there any more than we did.

A socialist tech industry would allocate resources to projects that benefited the workers themselves, both inside and outside of tech. If we truly want to “save the world” as so many Silicon Valley millionaires claim to want to do, we need to organize against an economic system that will provide funding for hundreds of advertising startups before it provides housing or healthcare to those who can’t afford it.

To get there, though, we must refuse to be satisfied with catered lunches, and fight alongside all workers, who provide the services and infrastructure that allow Mark Zuckerberg to accumulate so much wealth. Nothing frightens capitalists more than solidarity, a truth which recently became more evident in the tech industry when startup Lanetix laid off engineers after they petitioned to unionize. Those engineers are now taking their case to the National Labor Relations Board.

We must refuse to be intimidated by bosses’ scare tactics. We must refuse to be pacified with paid vacations. When we fight, we win.

Featured in Technology and The Worker (#2)

author

Scott Surette (@scottsurette)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Open Source is Not Enough

by

James Halliday

/

May 7, 2018