Nicosia calling

by

Jane Chelioudaki

October 7, 2020

Featured in From the Workplace (#13)

an inquiry into a call centre in Cyprus

inquiry

Nicosia calling

by

Jane Chelioudaki

/

Oct. 7, 2020

in

From the Workplace

(#13)

an inquiry into a call centre in Cyprus

It is said that call centres are the factory floors of the 21st century. In the piece that follows I am going to describe my experience working in one of them. An experience that has traumatized me in many ways but still an experience very valuable concerning my understanding of organizing myself and my coworkers. I hope that by publishing it, this experience will be a companion to my fellow workers around the world.

I was born in Greece and I have a Bachelors in English Language and Literature. Having to work for a living from an early age, I became active in many political worker organizations and trade unions while living in Greece. In 2019 I migrated to Cyprus and joined the Industrial Workers of the World. It was, and still is, very difficult to find a decent job in Nicosia, the capital of the island, especially when you are a migrant with no connections whatsoever, so I accepted a job offer at an insurance company call center.

The call centre is actually a branch of a larger company located in Greece, which itself is a subsidiary of a Dutch firm. As a result, we do not have any contact with our employer, only with mid-level management. The workforce of the company mostly consists of two groups of workers, a small group of back-office employees and a larger group of call centre representatives; other than having different duties, the only difference between the two groups, that I am aware of, is that the former work on a steady schedule while the latter are on a random shift schedule. I work as a call centre representative, so I am going to write about that experience here.

The call center deals with a number of duties quite complicated that need the worker’s full attention in order to avoid mistakes which can lead to the further suffering of the worker. We are trained to handle two main categories: car insurance and home insurance. Each of them has a sales and a service subcategory. When we answer calls concerning the sales department we are supposed to promote insurance products and sell policies and when we answer service calls we help already existing clients with their insurance policies, questions they may have, changes they want to make, payments etc. The service part is awful as there we deal with all the complaints and the angry customers and also we read legal texts to them asking for their consent for changes to be made. Those legal texts are very specific in what the worker has to say and what information, dates etc they have to include so we need to be concentrated and often with a yelling client over our heads that is almost impossible. If mistakes are made we often receive harsh criticism from the management who explicitly require that “NO MISTAKES MUST BE MADE”. Many times they try to terrorize us by describing the consequences that the company will endure in that case, and subsequently our job performance. We also make outbound calls and handle a number of tasks given by the management. For example we call clients that have emailed the company asking for an insurance offer or we call clients to inform them that their insurance is cancelled or the change they are requesting cannot be done leading us to receiving even more yelling. We are also advised not to connect the angry clients with management even when they are asking for them, and we are told to say “I am the manager of your contract and I am responsible to help you”. That infuriates the clients even more and we end up swallowing all the falsely directed anger.

There are around eleven call centre representatives working for the company, from young people paying for their studies to people with families and children. Most work full-time (eight hours a day), while the rest, like me, work on a part-time basis (four hours a day). We are not officially employees of the insurance company; we work for what can best be described as a shell company, which our actual employer created and paid the company’s personnel trainer an extra 100 euros to appear as one of the directors.1 We are supervised by two team leaders, who used to be call centre representatives themselves. Both management and workforce are almost exclusively female, with most workers being Greek-Cypriot and the rest migrants from Greece like myself.

The training process

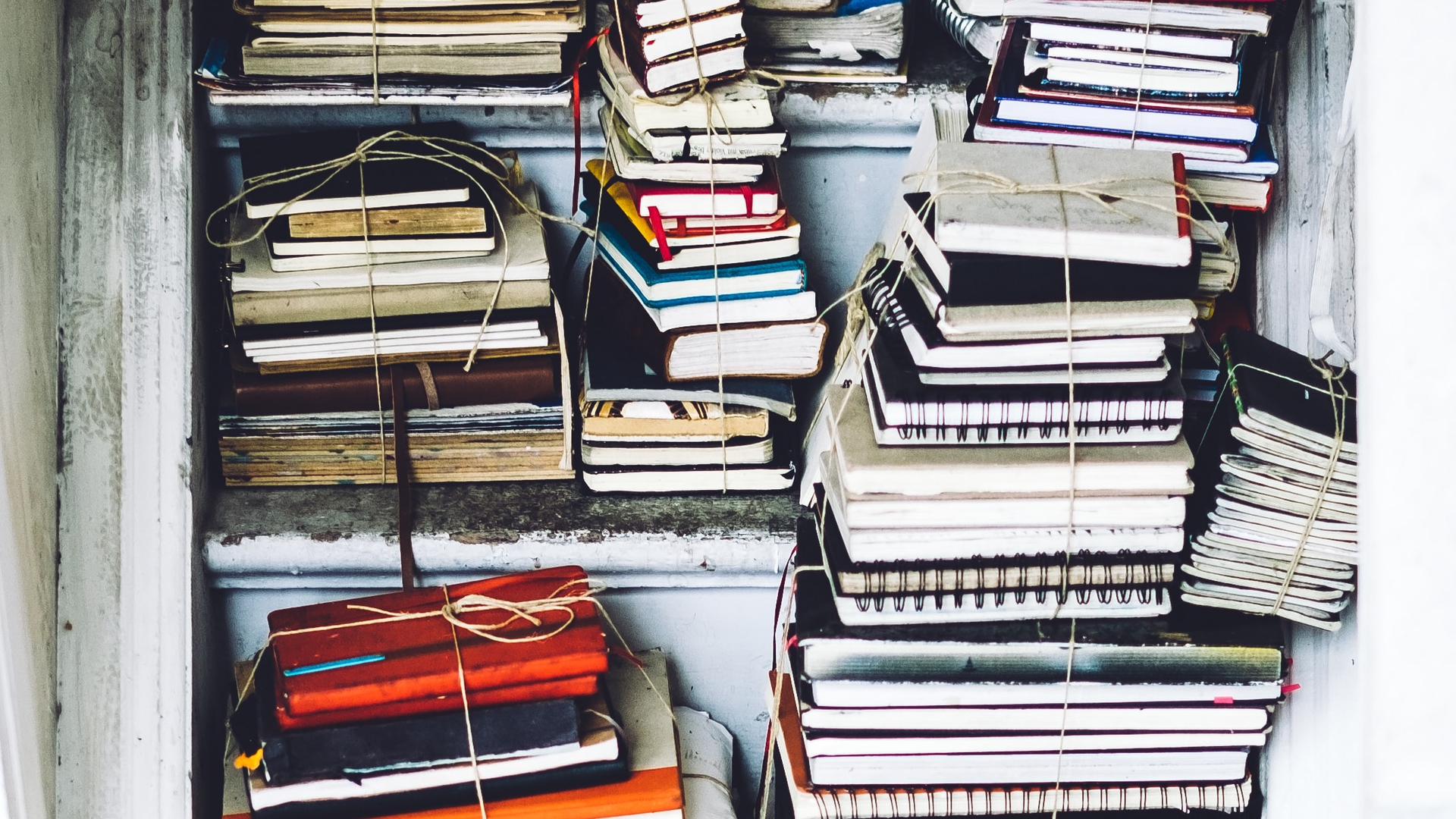

I began working for the company almost a year ago, I was hired along with five other women. During the interview we were informed that we must go through two weeks of training and then take an exam and become certified insurance agents, in order to be able to properly work for the company. Those exams are mandatory for someone to be able to work in an insurance company in Cyprus. There are a number of certificates to be taken but the obligatory ones are the first two that are included in the first level, the Basic knowledge of Insurance. The first level includes two books, 100 pages each, full of legal, financial and insurance regulations and therefore they are quite hard and extremely time-consuming to memorize. We were getting paid during the training, and the exam’s costs would be provided by the company; it was only after we began our training that we found out that it would be extended to three weeks and that there would be two consecutive exams instead of one, a month after the training was to be completed. That meant that for almost two months our entire “free time” was devoted to studying rather hard and complicated information, because if we failed either test we would have to pay ourselves for the opportunity to take it again. Not to mention that many of the trainees, including me, were completely unfamiliar with studying such regulations. Furthermore, contrary to what the job description said, the work actually demanded extended computer knowledge, while many of the girls did not even own a computer. And that was not the worst part.

Our training under the personnel trainer was rife with insults, yells, humiliation and generally unacceptable and degrading behaviours. The worst had been the tests at the end of each week; the situation was made so dreadful by the trainer that people cried or fainted during these tests. One of my fellow workers started losing her hair due to stress and lack of sleep, while a couple of others had to turn to a psychiatrist for prescriptions of sedatives to cope with it. This situation was especially hard on the mothers in the group – I remember countless phone calls of desperation due to sleepless nights, as the only time they could study was when the babies and kids were asleep. Things got out of hand when one colleague made an insignificant mistake during a call and the reaction of the trainer was to violently grab and take off her headphones. She pulled so violently that our colleague’s head was dragged along and some of her hair got pulled with the headphones. All this oppression and the need to help each other led to the creation of strong personal bonds between us, and eventually a united cry against the abuse took place, in the form of formal complaints during the designated meeting with our team leaders. This bore significant results – the trainer was forced to completely change her attitude towards us and towards the group of workers that came after us, and she eventually left the company. However, those results came too late for two of my fellow trainees, who resigned before the exams took place. Most importantly, it was a situation that management was clearly aware of, since employees who were already working for the company had a similar experience. It was a lesson for at least some of them that in order for changes to take place, collective action is needed.

First impressions (are never right)

It is important to note that initially everyone was excited about working for this insurance company, mostly due to the five-day work week and the paid sick leave that it provided. We were interviewed by two young happy looking women (the personnel trainer and one of the team leaders) and during the interview we were told that although the work is quite stressful and we would be put under a lot of pressure, the company has a lot of rewarding policies and we would have chances for promotion very soon. The first part was proven correct; while at first we were told that we were only going to do phone calls about sales, during our second week of training the team leaders announced that we are to take up service phone calls as well. These are much more difficult than sales since they not only require much more experience, knowledge and familiarity with the work, but on top of that you are often faced with an angry unsatisfied customer who is not above insulting and swearing at you. The latter part about rewarding policies and chances of promotion was a blatant lie. The pay is just a few euros above minimum wage2, their rewards are gift cards for certain shops and there are neither pay raises nor chances of promotion – unless a team leader quits in the future. Furthermore, overtime, which part-time workers are often called on to do, is paid on a 1:1 basis. Moreover, although it is very rare that our last phone call will finish right at the end of our shift, overtime only counts if we complete at least thirty minutes of work after our shift has finished. Last but not least, although the company does provide full pay if we miss up to three days of work each month due to sickness, the team leaders are prone to pressure us to come to work while we are sick.

Even before we came to realize the harshness of the job, certain events, combined with the aforementioned behaviour of our trainer, began to dent the friendly family-like atmosphere that the team leaders were trying so hard to cultivate. We only found out that we were not officially employed by the insurance company when the head of HR brought us our contracts to sign during our second week of training. Some of us demanded copies of our signed contracts and the confidentiality agreement, and we were promised that we would get them as soon as they were signed by the headquarters in Greece. Two months later and after a number of emails to the head of HR demanding she provides the papers, we were informed that they were misplaced and we had to sign them again. When the contracts finally arrived we realised that they were very roughly written. Important personal information such as social security numbers and id numbers were missing, while many other sections regarding our earnings were completely blank or crossed out. Moreover, they even went as far as to refuse to give us a copy of the confidentiality agreement because, they said, it was the company’s property and we were not allowed to have a copy. Only a few of us, aware of our rights, did not accept that excuse and strongly insisted on receiving a copy of anything that contained our signature, and eventually we got it, contrary to those who did not insist. This event cracked the facade of the company’s professionalism, and further cultivated the awareness that knowing our rights and making demands accordingly was the only way to get results, an awareness that would become crucial in the weeks that followed.

The day of the exams was the first chance we got to meet outside of work and away from the supervision of our managers. We were a mixed group of newly hired employees and people who had been working for the company a few months already. As the discussion went on, we realized that we were all very dissatisfied with the workload, the long working hours, the unpaid overtime and the behaviour of some of the team leaders including the trainer mentioned above. The conversation was heated and a lot of us sounded very decisive and willing to take action. The beauty in all that was that even though we all recognized that we had different needs, some of us more urgent than others, we did not let that get in the way at the time and we were all united in agreeing that we needed better wages. It did not matter if it was for more beers or for more diapers. We were all in this together and as a result strong bonds started forming. We did not seek help from our team leaders any more but mostly from each other and the atmosphere at work was starting to feel really hostile against management. We knew everything that happened to each of us, every angry manager email. We knew about every insult, every incident, big or small, because we had established a strong network of communication.

The overtime strike

Soon after, I was approached by one of the other part-timers who wanted to become a full-time employee. Cyprus labour law demands that such requests are at least acknowledged by employers, and that satisfying those employees must be prioritized over hiring new people. However, the company was not interested since the four of us who were part-timers were providing them with the needed work by working overtime whenever they asked us to. After realizing that we were paid overtime as regular working hours (which we had to figure out by doing the calculations ourselves since our contracts were missing information and our superiors avoided answering our questions about this), my colleague proposed that we stopped working overtime. We discussed it with the other two in order to have a coordinated struggle so that none of us would work overtime until they raised the remuneration as well as provide our colleague with a full-time job. For approximately one month no part-timer was working overtime, which got the managers riled up since they could sense that we were all in this together, even if we had not come forward yet. They sent assessment forms and anonymous questionnaires regarding working conditions, manager behaviour, etc., to all of us working the phones, and although we had not planned it we all complained about the behaviour of the trainer and the team leaders.

Almost immediately after we submitted them, meetings of two or three employees with team leaders were called, where we all had to repeat what we had written, not anonymously any more, and within a week the trainer “quit” and the team leaders adjusted their behaviour. With the unofficial “overtime strike” still going on, management concluded that we were in need of better communication. One-to-one and team meetings entered the weekly agenda, in which team leaders had these notebooks where they would write down anything the employee complained about and after the session the employee would actually feel relieved even though absolutely nothing had changed in their reality. The group meetings were a chance to speak up about the most burning issues, like better wages, unpaid overtime and a lighter workload, and to see where our co-workers were standing after observing the blatant refusal of management to talk about these issues. However, the one-to-one meetings worked in the company’s favour since some of our co-workers started feeling that the managers were their friends who honestly wanted to support them.

Vis-a-vis the “overtime strike”, certain obstacles to communication and coordination had arisen that let to misunderstandings and mistakes, the most important of which being that we had not managed to meet up and officially announce our reasons to the managers, resulting in the unceremonious end of the strike, which caused rifts between us. At that point we did not have the discipline, determination and coordination necessary to organise a struggle, due to a lack of consciousness that we should be united as workers with common concerns and interests. Our relationship was based instead on liking each other to the point of becoming friends. The failure of the “overtime strike” demonstrated the necessity of developing stronger relations and a more steady communication network - a necessity intensified by the fact that already some of us had left the company, while new people were being hired. The opportunity presented itself when a member of a group of newly hired employees took the initiative of creating a Viber group3 for all of us call centre representatives, mostly for chatting and sharing work information such as the work schedule. I helped her gather everybody’s information, in the hopes that having more public-like discussions would help form solidarity bonds between us. In that same spirit I decided to create a private Facebook group, as a safe place where we could exchange experiences of work, difficult experiences as well as generally support each other and have more work-related discussions, instead of friendly chit-chats. I started by posting memes relevant to our workplace experiences, and at first it went extremely well as everybody had accepted the invitation to the group and many were reacting favourably to the posts.

Management’s response

However, a couple of weeks after creating it I was called into a private meeting with the highest on-site manager, whom none of us had spoken to before. She showed a rather hostile behaviour in the beginning, questioning my motives for creating the Facebook group and clearly implying that the page should be shut down, going as far as telling me that each and every one of the employees would be called in to be questioned regarding the group and their participation in it. I interpreted this as an attack on my rights to have a personal life and I actually managed to make her completely alter her attitude, at which point she started explaining herself, claiming that she was worried about us and our happiness in the company and that she was doing everything she could to create a more pleasant environment for us and emphasising that we should be patient.

When I got home I informed all my coworkers about what happened. Despite the manager’s threats proving to be empty, during our scheduled meeting the team leaders kept repeating that we were being manipulated by evil colleagues and that the precious family atmosphere of the company should be maintained. This, in addition to the company doing its best to grant any wish employees had, unless it was related to wages in any way, got some co-workers to take management’s side, while most of the rest stopped reacting to the posts and used the Viber group mostly to exchange pleasantries. The worst part was that the most active among us became worried and suspicious about who informed management about the group, since it was a private one, and those suspicions were, and still are, making any organising efforts extremely difficult.

It soon became obvious that the only way to build the necessary trust in order to form some sort of collective with my co-workers, would be to follow the company’s tactic and meet with them privately one by one. It was a slow process but a rather valuable one as it helped me have a more rounded picture about what was going on in their lives and what challenges they were facing. My main goal was to achieve a gathering with the majority of the employees to discuss and take action on issues that all of us had expressed dissatisfaction about, and after roughly two months we had a group of six workers interested in doing so. This group not only represented almost half of the call centre representatives in the company, but also the diversity of the workforce: part-time and full-time employees, some working there for years and some just a couple of months, young students and middle-aged mothers, native Cypriots and migrants from Greece. Although this was a very positive outcome, it made meeting all together impossible. Our extremely different lives and responsibilities outside of work, coupled with different shifts and breaks at work as well as the fact that we lived far away from each other resulted in deciding to organise our first meeting with only four of us.

The absence of the two coworkers created a disappointing atmosphere and it was made clear that whining about our jobs was the main priority. Unfortunately, what i came to understand was that my coworkers would just enjoy complaining and sharing bad experiences from work, and every time there was a suggestion for an actual action against all those awful working conditions, they would just ignore it. Whining relieves the anger, sharing it relieves it even more. In my experience, complaining that does not result in something concrete like an action, any action taken, is pointless and harmful to organizing. We managed nonetheless to come up with a plan of action. We created a list of demands to improve working conditions and wages, and decided to try to convince as many of our colleagues to sign it before presenting it to management at a team meeting. This plan seemed agreeable with everyone since it was following the instructions of our team leaders that we should inform them about any and every complaint we had. However, by doing so collectively instead of individually, and using this opportunity to connect with our colleagues, we hoped to turn the company’s tactics against it. We spent hours coming up with the demands, exploring the possible negative consequences of our action and discussing the fact that this action would probably yield only limited results, so more drastic measures would be necessary in the future, after we had convinced more people to join us. All four of us signed the list of demands and the meeting ended on a positive note. However, in the next couple of days two of the signatories called me to withdraw their signatures for various reasons, including pressures from home not to get involved in anything like this.

This development left the group with only four members and a heavy atmosphere of despair and hopelessness, which resulted not only in more limited demands but also in a lot of procrastination regarding their finalisation . Management intensified its efforts to marginalize the voices of discontent within the workforce, which, combined with an increased workload, on the one hand made people angrier with the company, but on the other hand made them too tired and afraid to do anything about it.

International Working Women’s Day organising

After weeks of general inaction, a feminist initiative calling for a one-hour symbolic strike on International Working Women’s Day provided what seemed to be a perfect opportunity to shake things up. The initiative was supported by not only the major trade unions in the country, but also every political party, the government and even some employers’ organisations. As a result it got a lot of positive publicity in the media. Moreover, the symbolic picket line in Nicosia was going to pass right in front of our workplace, which is made up almost entirely of women. I was hoping that under those conditions at least a couple of my colleagues would join me at the protest.

Sadly, I underestimated the fact that these kinds of actions are completely foreign to most workers in the private sector on the island, and especially the younger ones. The only support I got from the co-workers closest to me was moral. On the other hand, when I made a formal announcement of my intentions to a manager during a team meeting, they were very supportive of my decision while one of my colleagues attacked me by questioning the strike’s aims as well as the women’s struggle itself. When the time came, I put a post-it note on my computer with strike on it and left the premises, and the only reaction I got was everybody’s startled gaze on my back. All in all, it was a quite empowering experience, since the protest was very successful with hundreds of women forming a miles-long picket line passing right in front of our office’s windows. However, management handled the whole event quite smartly. An unscheduled training session was organised during the protest so the employees would not get to see what was going on outside. They also did not dock my pay for the hour of the strike, making sure I had nothing to complain about.

In preparation for the Women’s Day strike, I went to the headquarters of the largest trade union in Cyprus to get informed about the necessary steps to take part in the strike, and the organiser responsible for insurance companies encouraged me to get a group of colleagues to meet with him to discuss what the union can do to help us. I am highly critical of major trade unions and the mitigating role they play in industrial relations, and if I followed this path there was a considerable risk of alienating some co-workers since this particular union is strongly affiliated with the main “Left” party in Cyprus.4 However, at that point (re)legitimizing our struggle against management through the support of a major and influential organisation seemed the only option, especially since the morale of our group was at its lowest. True enough, there was a lot of interest in meeting with the union, even from coworkers outside of our group that we approached with the idea. I made an appointment with the organiser to discuss the details of the meeting. Unfortunately, the day before that appointment the coronavirus disease struck the island. The appointment was cancelled and all of our plans went down the drain.

Covid-19 and beyond

The company handled the Covid-19 situation very professionally and responsibly. It initially sent some of us to work from home for the obligatory distancing to be maintained, and during the two months of lock-down all of us worked from home. This situation, however pleasant it seemed at first, caused issues to many of us, such as invasion of private space and more stress. Our homes turned into workplaces and in many cases hostile ones, since the team leaders managed to use technology in such ways as to control us even more, creating very stressful atmospheres in our very homes. Working from home also created tensions amongst families and roommates as during work hours there had to be complete silence, a situation unnatural for children and highly annoying for the rest.

Also, the company provided us with a symbolic monetary present for Easter, and in May they announced that the shell company we work for would be disbanded and we would all be transferred to the official workforce of the insurance company. This will bring us certain benefits, including a 13th month’s wage,5 which was a consistent demand of call centre representatives since our team leaders were working the phones. Of course, upper management tried to take credit for negotiating this deal with the company. This all happened while financial and employment insecurity was rampant around the country, with many companies cutting wages or firing their employees. Under these circumstances, our company has managed to restore its family-like image in the eyes of most co-workers. There are still some who are highly critical of the company’s plans and wanting more pay for their work, as well as understanding that any positive change is in direct relation with our actions and demands, however fragmentary and disorganised they were. Be that as it may, with three months of almost non-existent organising, or even physical contact since half of us are still working from home, most choose to quit the company rather than fight for change.

In conclusion, it is important to examine some of the obstacles and challenges that prevented the development of a well-organised united employee initiative. First off, the company, through its team leaders, meticulously tries to maintain the false impression of a relaxed and friendly work environment and a family-like relationship between management and the workforce, going as far as being quite accommodating to almost any personal demand or request that is not related to wages. The atrocious behaviour of the personnel trainer helped us (and the colleagues who were working there before us) to see past the facade, but our early success in putting a stop to her abuse meant that the employees who were hired after our group did not share our experience, nor did they develop the same solidarity bonds we did.

Perhaps the most significant obstacle for developing those bonds was the high worker turnover of the company. A couple of months before I was hired there, the majority of call centre representatives quit in protest against the unacceptable labour conditions. In the first two months of working there my group of six was cut in half, with the third member of the group being fired just after the exams, and two more of the employees already working there quit. There was a group of hirings that followed ours, and at the time of writing half of them have also quit. This situation not only hindered the formation of strong relationships between us, but also created two groups of dissatisfied but reluctant to react employees: those who viewed the job as temporary and were unwilling to go through the unpleasantness of fighting for change, preferring to quit when the pressure exceeded their limits, and those who needed to keep working there and were afraid of losing their job if they reacted, requiring a certain level of “safety in numbers” in order to get seriously involved in any form of struggle against the company – a safety that the first group was depriving them of.

Another salient obstacle was the difficulties we faced in meeting in person, due to familial obligations, university studies, long distances and, perhaps most importantly, different working hours and breaks. With management’s successful efforts to scare people away from using the social media outlets to communicate their grievances in a more collective manner, being unable to meet not only made coordinating any form of action more laborious and time-consuming, but also deprived us of the feeling of empowerment that comes with discussing common problems, solutions and actions with a group - an empowerment that is made even more crucial by the almost complete lack of worker struggle culture within the Cypriot workforce. This situation created a certain level of alienation between us, and overcoming it was a precondition before any form of organising took place. However, the high turnover mentioned before meant that we often just did not have the necessary time to achieve all these goals.

Organizing efforts and struggles are full of ups and downs. We’re supposed to find comfort and inspiration in the ups and learn from the downs. After all, it is a centuries-old battle, but the fact that it is still being fought is all the comfort and strength we workers need.

-

It is useful to keep in mind that Cyprus features prominently in the Panama Papers, and such practices are common. To get an idea about how these companies work, see “The Laundromat” (2019). ↩

-

In Cyprus there is not a universal minimum wage; there are various minimum wages defined either by law or collective agreements that only cover certain occupations (ours is not one of them), and most of them are around 850 euros gross. ↩

-

Viber is a cross-platform voice and instant message app ↩

-

Every major trade union on the island is affiliated with a political party, and most Cypriots are highly political, though on a very superficial level. They choose and fanatically support their respective political party/trade union the same way and manner as they do their favourite football team; in fact, the major football teams have strong ties with political parties too. ↩

-

The 13th (and 14th) wage represents a practice, common in Cyprus and Greece before the 2009 financial crisis, according to which employers would give employees an extra “wage” during the Christmas (and Easter) holidays; the amount of money would not necessarily be that of a full month’s paycheck but what’s important is that if the 13th wage was included in the employment agreement (individual or collective) or if it was given for a number of years, it becomes mandatory for the employer to provide it. ↩

Featured in From the Workplace (#13)

author

Jane Chelioudaki

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Introduction: Why Worker Writing Matters

by

Notes from Below

/

Oct. 7, 2020