The Ivy House Union

by

Amardeep Singh Dhillon (@amardeepsinghd),

Michelle Gorman,

Conrad Moriarty-Cole,

George Briley (@GeoSBriles)

March 24, 2019

Transforming finance conference

inquiry

The Ivy House Union

Transforming finance conference

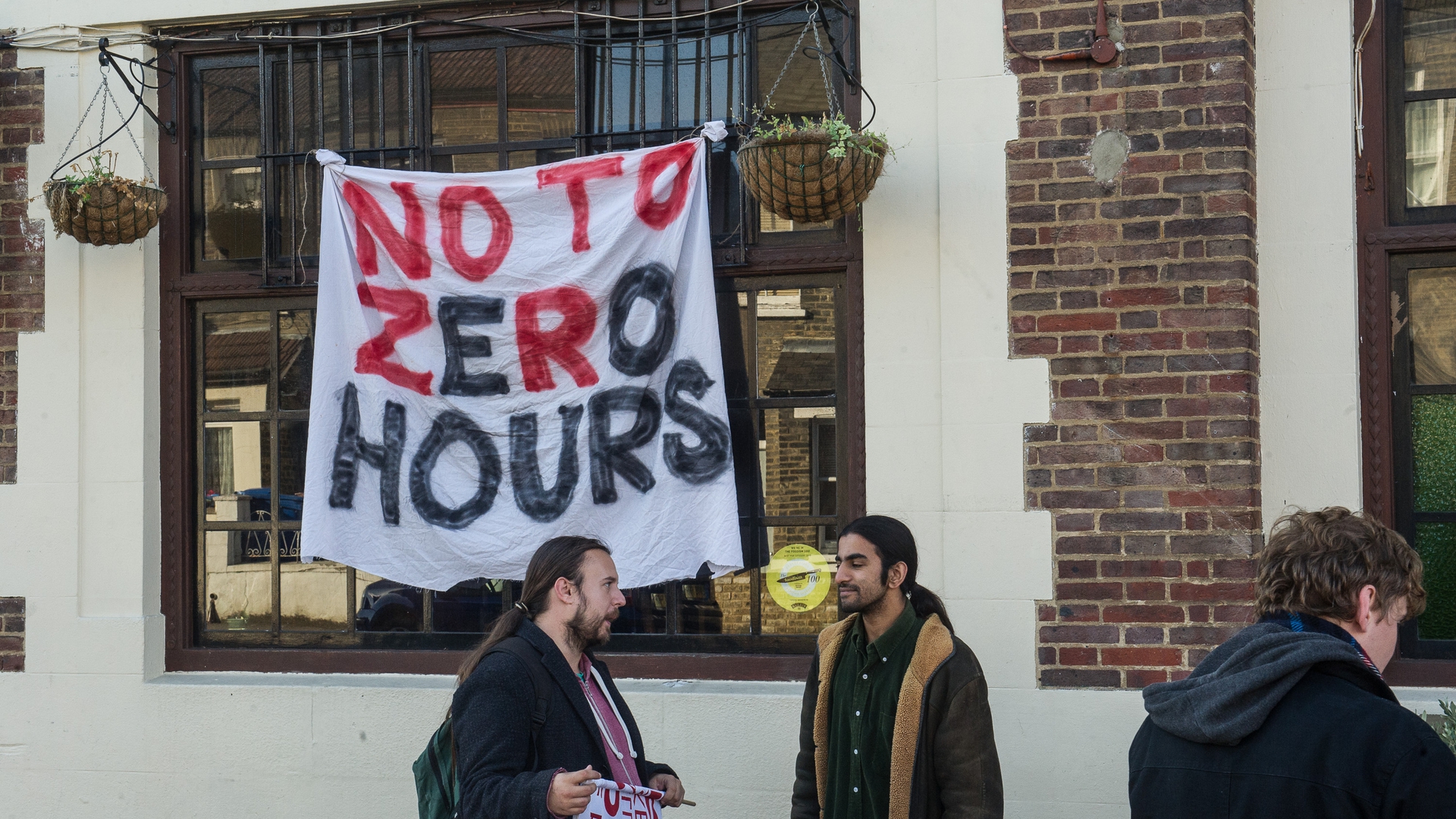

Conference paper delivered at Transforming Finance organised by People’s Private Equity and Greenwich Political Research Center. Photos by Guy Smallman

On 30th September, 2018, staff at the The Ivy House Community pub, a cooperatively owned pub in Nunhead, South East London (the first cooperatively owned pub in London), took spontaneous emergency strike action. The wildcat strike was a response to the effective dismissal of four members of the pub by the management committee, a steering group made up of twelve shareholders whose primary function is that of a board of executives. It must be stated (for legal reasons probably) from the start that the decision to take wildcat strike action was a choice taken solely by the workers, and should not be seen as endorsed, organised or supported by our trade union the Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (BFAWU). Following a request by middle management for a reason for the effective dismissal of the staff with no notice given, the management committee replied that they had “no obligation to go into the reasons why” because the staff were on zero hours contracts. This was the final straw for staff who had been requesting an end to zero-hour contracts for years, not to mention enduring a string of negligent and abusive General Managers.

The staff had three basic demands: 1) that The Ivy House commit to no longer offering zero-hours contracts, and to transition all existing staff onto fixed-hour contracts, 2) that the four members effectively dismissed be reinstated and in-house disciplinary procedure followed with immediate effect, and 3) the immediate commencement of union recognition with the BFAWU.

After a tense and tiring three days on the picket line, and heated negotiations with the management committee, a resolution was found on the 2nd of October. The committee finally agreed, in principle, to all three demands; marking what may well be an historic victory for pub workers. There is no doubt that the unique context of the pub as a community coop aided the workers cause. This is evident when we compare the fight at The Ivy House to the ongoing struggles at Wetherspoons and Antics pubs.

Yet, by the same token, the question we must ask is: why and how did this happen in a community coop the first place? I’m going to talk a bit about this with the aim of highlighting the problem with discussing the coop movement as homogenous, when exploitative and unethical employment practices can and do take place within it. Coops should be about attacking normative and alienating logics and relations of production within the workspace, yet all too often workplaces like The Ivy House reproduce the hegemonic logic of “business first” over and above the wellbeing of employees. We wish to suggest that a democratic worker cooperative model can in fact hold a greater opportunity for inclusive community utilisation and wealth, and is to be prefered over a community or consumer-owed model. Unfortunately, in the case of The Ivy House there remains a hard limitation written into the society rules regarding worker ownership. However, we wish to mobilise our particular understanding and knowledge of how work is produced and reproduced on the shop floor, to develop demands that move from the ideal of community ownership, to that of community-serving work.

We hope that our experiences at The Ivy House can serve as an example to be learnt from, and that it might set an encouraging precedent for hospitality workers in pubs and clubs. Shop-floor organising is extremely difficult in hospitality, a fact accountable to several causal factors, not least the transient nature of the workforce. Organising at The Ivy House began three years ago in 2016 around the issue of zero-hours contracts, and it was not until 2018 that we reached density. Momentum was slowly built by continually subordinating management in a string of small-scale battles, including the removal of two successive General Managers who had been appointed by the management committee. The last of these two bosses deposed by the workers began in August 2018. An intensification of harassing, bullying and discriminatory behaviour acted as the catalyst for unionisation. Once unionised, we were able to coordinate a series of formal and informal grievances that led to the investigation and eventual dismissal of the GM.

The story of the General Manager’s dismissal, however, serves not only as an example of the importance of workplace organising but points to the flawed labour-management relations that have persisted in the pub since it reopened as a community cooperative in 2013. The GM position has been a chronic issue which could have been addressed years ago if the staff had been involved in the hiring process, however, the attitude of the management committee towards staff is representative of an industry-wide lack of respect and condescension concerning the expertise of staff regarding the running of a business. I’m aware that no industry I know of affords the staff the chance to choose their boss, but there was a seemingly deliberate disregard on the part of the committee to appoint a GM who at least would be a “good fit” with existing staff. At one point the committee even expressed the desire for a “Al Murray type figure”.

A further example of strained labour-management relations is the issue of zero-hour contracts. Staff have been requesting an end to these exploitative contacts since 2016, when a letter signed by all staff including the then General Manager (one of the only decent ones) was given to the management committee. The response letter abdicated responsibility in saying the decision was at the discretion of the general manager. However, the general manager who co-signed the letter to the committee along with the rest of the staff had never had such an option to offer fix-hour contracts. By the time the response letter came through, he had resigned. This meant that it was then up to the next General Manager, who agreed to offer fixed-hour contracts. However, he never produced the contract for staff to choose if they so wished. The next general manager after that was equally unresponsive in producing a fixed-hour contract. Staff also continued to requested fixed-hour contracts from the committee leading up to the strike to no avail. This suggests an ambiguity surrounding responsibility and roles of the management and the management committee, which was a contributing factor leading up the strike that in fact still persists.

An important point to make is that much of the tension between workers and management stems from a fundamental ideological divide over what the pub represents. In terms of its practises as a business—paying the London Living Wage, for example—The Ivy House stands out in some regards comparative to other hospitality jobs in the city as offering a pretty good deal. But a non-profit business offers new possibilities, and as workers we hold the pub to a higher standard because of its grand claims of community culture. It is not ingratitude but a desire for the The Ivy House to act as a blueprint for industry-wide change that drives us to organise—the rarity of the opportunity we have at this pub is both the reason for our continued struggle and the privilege that means we are more likely to be heard than workers in most hospitality jobs.

It often comes as a shock to people who take an interest in the cooperative business model that the staff should not be afforded even the basics of job security and employment rights. The difference is that the pub is a community-owned coop, not a worker-owned coop. This distinction is not always made abundantly clear, which has given rise to the assumption that a community-run pub will operate in a similar way to a workers coop, which would have the rights and concerns of the workers at the forefront of the business model. But in fact, the community veneer enables the reproduction of your run-of-the mill employment malpractices within the cooperative movement. It’s apt to note here that The Ivy House was the first pub in the UK to be listed as an Asset of Community Value, and the first building to be bought under the “community right to bid” provisions of the 2011 Localism Act. Unfortunately, the Big Society policies of David Cameron’s conservative government didn’t stipulate the need for worker-oriented workplace practices.

The question of what community is or can be is given in the ongoing practices of running the pub and the decisions made about how it should be run. Is community definable by a shared asset to be maintained at any cost? Or should community not be defined first and foremost by mutual aid? If the core purpose of a cooperatively-owned community pub is to maintain the business to the benefit of the community, it stands to reason that the employees—who are also members of the community—should be afforded at minimum the basic right of job security, if not much more besides.

The Ivy House, as a community-owned cooperative, is registered as a not-for-profit. With capital removed from the authority position, what then legitimises the authority of the management committee to make the decision that the workers should not genuinely be included as equal beneficiaries of a community project? Is the social capital they gain in their position as committee members of a community-owned cooperative enough? The demographic of the shareholders of The Ivy House (being majority white and middle class) only partially reflects the community living in Nunhead and Peckham where the pub is located. And the demographic of the committee itself reflects a particularly unrepresentative subsection of the shareholders in general. As such, their investment in the pub as a community-oriented project need not be called into question to also suggest that a group of lawyers, business owners, and management consultants who have little to no experience of being an employee in the hospitality industry will not necessarily hold the same politics as the workforce they employ.

Moreover, in the case of a cooperatively-owned pub of this nature, the demographic of the management committee not only impacts the workers but also the local community. The management committee’s perception of the customers who the pub serves is rooted in their social positioning, and this self-recognition in the abstract customer leads to the exclusion of certain demographics, including the workers as customers or community members. More specifically, the ethnic and class diversity of the area is belied by the events and music (that is only noticeable by its absence), and the scarcity of low-cost drinks shuts out potential customers from a lower socio-economic background.

It’s also important to remember that it is perhaps unfeasible to transfer the business model of The Ivy House to a worker co-op style of management. The business model is rooted in social capital and the question of how many customers would continue patronising a pub that they did not have a personal attachment to via community members involved in management, remains unanswered.

Considering this, we hope to move the pub from being simply community owned to community serving. This means that, for the future, our short and medium-term goals include full union recognition, the complete resolution of the demands agreed to post industrial action, and moves towards greater worker involvement in the decision-making processes regarding the running of the business. One example would be to enable staff to either buy or accrue the means to buy shares, and therefore potentially be eligible to be elected to the management committee. (This is as yet untried and has the potential for many ethical and relational minefields to be navigated.) We are also seeking to improve worker access and organisational powers in the community-led and community serving activities that take place in the pub, both in terms of events and work practices. Can we be more environmentally friendly, for instance? Or engage a wider demographic of the community which the workforce reflects?

A fundamental question remains, why would worker ownership be something that workers would desire? In furthering worker ownership in the hospitality sector, the transient nature presumed in many of these jobs is not something that can be ignored. Many people are primarily engaged in hospitality work as a means of funding endeavours elsewhere, and may find the potential added responsibilities or complexities to be beyond what they are willing or capable of committing to. Therefore, should a more worker-controlled environment arise, would the hiring of employees become more selective, or even exclusionary? Or is there a way in which greater worker involvement can be respectfully engendered and developed? Moreover, if we understand worker ownership to facilitate community serving work, how do we socialise the responsibility of ownership, lowering the barriers to engagement and making it accessible to a transient and diverse workforce?

Ultimately, The Ivy House case is both a testament to power of collective organising and a warning as to the limitations of community projects. It offers a glimpse at the radical potentiality of non-profit community spaces and reinscribes the limitations of their ideological base. Greater worker control in the hospitality sector, if it happens, will be incremental—we’re proud to have taken the first steps towards it, and offer The Ivy House as a space in which to open up the conversation beyond our own situation.

authors

Amardeep Singh Dhillon (@amardeepsinghd)

Michelle Gorman

Conrad Moriarty-Cole

George Briley (@GeoSBriles)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next