Critique of Political Video Games

by

Marijam Didžgalvytė (@marijamdid)

June 25, 2019

Featured in Workers Game Jam (#9)

How is the GWU UK Game Jam Different?

inquiry

Critique of Political Video Games

by

Marijam Didžgalvytė

/

June 25, 2019

in

Workers Game Jam

(#9)

How is the GWU UK Game Jam Different?

Not gonna lie, as soon as I hear of an attempt to inject progressive themes into videogames, usually I cringe. This is a trend that began with innocent projects like Re-Mission (2006), for instance - a game that invites players to fight inside the bodies of fictional cancer patients and destroy the cells that cause cancer, raising awareness in the process. Similarly, Get Water! (2013), puts the player in the role of an Indian girl who wants to study, but keeps on getting interrupted by the need to go and collect water. This trend of ‘socially aware’ games culminated with the global success of Papers, Please (2013). This border simulator sky-rocketed its author Lucas Pope to the hall of fame of worshipped and most-awarded games developers.

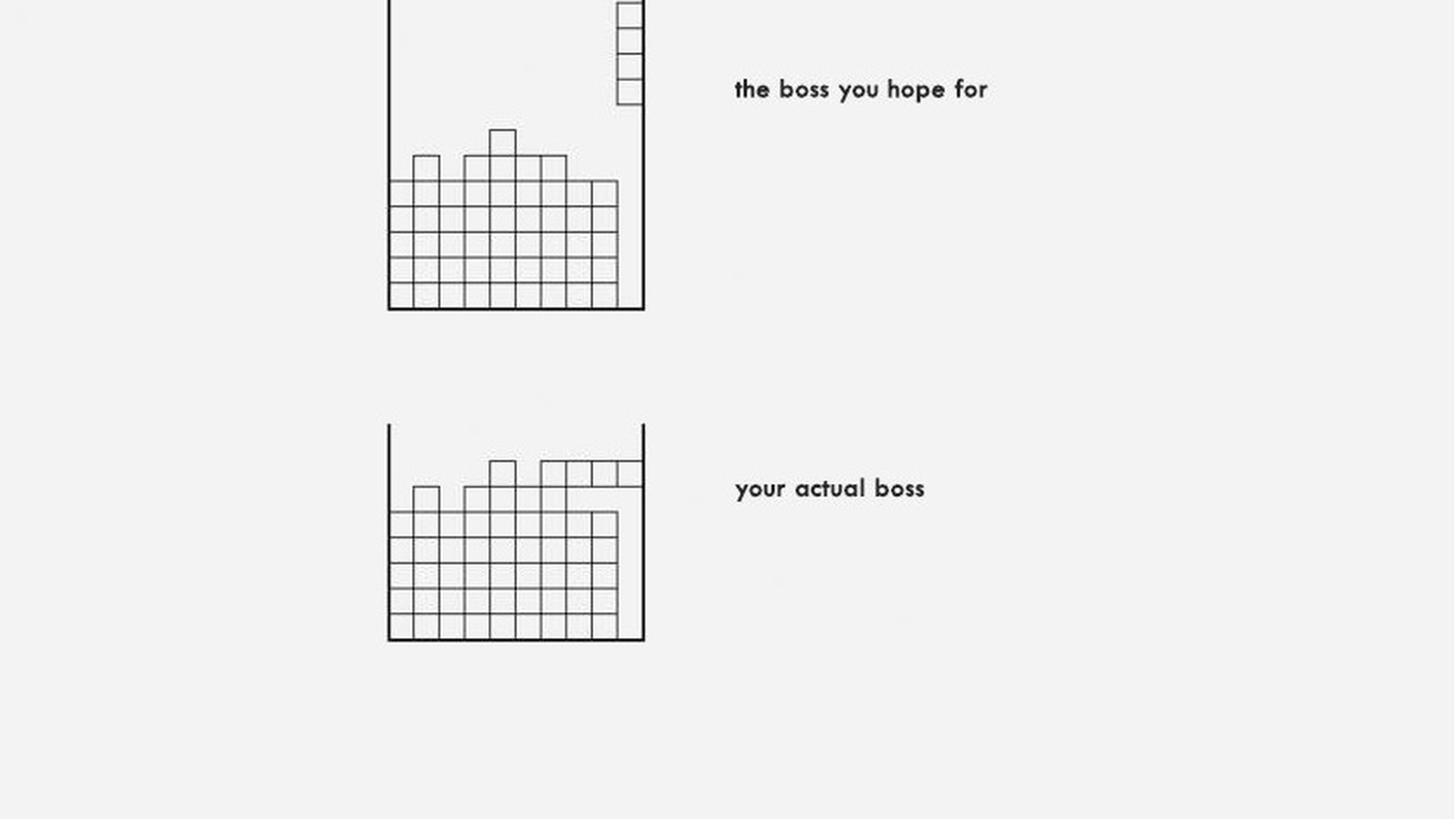

Such games often fail to make an impact, despite using a medium that has such a potential to be engaging. The player is likely to already suspect the terms of engagement, with a predisposed attitude, that leaves little to alter.

With all the best intentions, these kind of artistic practices fall into a category of mundane preaching, leaving one guilty rather than empowered. Or in a worst case scenario, these objects get purely recuperated and used as a tool in promoting equally oppressive structures. Just look at the likes of highly praised games designer Jane McGonigal who celebrates games for good whilst at the same time working for organisations like the World Bank, McDonalds and U.S. Department of Defence. Surely that kind of artistic creations do not possess the energy charge the subject matter wishes it did. Groups cannot coherently advocate for decentralised, democratised systems without simultaneously working towards decentralised and democratised structures internally.

For these reasons, gaming is yet to be recognised as a legitimate resource or an inspiration for various political strategies. But in the event that it were, what would this look like? What would make gaming politically useful and why does that matter?

Now I have written previously about the fascinating political properties of Eve Online or the Uber Game, but today we can add a new event to this list - the recently concluded GWU UK/Notes from Below game jam themed ‘Organising at Work’. Those involved in endeavour were not aiming for the games themselves to be the only output, but rather the creation and celebration of new ways to organise at a workplace, create a political terrain that is dare I say it… great fun.

The big criticism that can correctly be heralded at political games is that they rarely address the modes of production - under what circumstances was the game made, who has benefited from the borrowing of the subject matter, is there a lasting effect to the messaging of these objects?

GWU UK suffers from no such problems - the games are created for fellow game workers by fellow game workers, all released for free on a small indie games-focused distribution website. The organisers of the game jam have even been thoughtful enough to give a whole month for the making of these prototypes, so that no developer would ‘crunch’ - spend an ungodly amount of hours on a game, abandoning their social life, or cutting out people with caring responsibilities, and so on.

And socialise they did! In pubs, across social media channels, in offices, at people’s homes - joking, coding, having drinks, eating pizza, nurturing the new political movement they have crafted. A lot of the people that have made contributions to the game jam are all developers involved in creating a worker-led game workers union and are curious about novel ways of organising and making the movement attractive to their non-political colleagues. Here, a game jam becomes a trojan horse for social reproduction, demystifying what being in a union means, and what class-based organising can be.

To zoom out - contemporary cultural thinker Stuart Hall, for instance, understood popular culture as an ongoing process in which relations of control and subordination are constantly shifting and certain cultural forms gain and lose support from institutions. Hall retained faith that culture was a site of “negotiation”, a space of give and take where intended meanings could be short-circuited.1 Crucially, though, he wasn’t merely interested in interpreting new forms, such as film or television, he was interested in understanding the various political, economic, or social forces that converged in these media how they were structured, packaged, and distributed.

In the GWU UK’s game jam, it is not the games as objects that were of importance, but the process of making them, the opportunity for establishing and maintaining solidarity, and the furthering of a concrete political project. The creators themselves are the ones affected by the stories and are the owners of the themes utilised in the games, negating the somewhat voyeuristic tendencies found in some political games.

Whilst trying to discuss political utility in videogaming, the obstacle that constantly reemerges is the means necessary to even engage with this medium. One would be correct when stating that videogaming can never be truly appropriated for radical purposes due to its sheer dependency on consoles / PCs and their production in the Global South, often in appalling conditions. The ethics behind the manufacturing of these devices has been a growing subject of concern for years - suicides at Chinese manufacturer Foxconn or conflict minerals required for most micro-chips that have funded genocide in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Video gaming holds immersive properties, unequalled to any other medium, it holds the potential to teach, train, help provide and share tools to destabilise the status quo, both implicitly and explicitly. This cannot, however, be separated from modes of production - any object that has ethics at its selling point can never truly be valid if it negates conditions necessary for it to exist. How can those conditions be challenged though? Workers organising, of course. Change is not going to come from the owners of factories and mines, structural and material change will have to be fought for by the workers themselves. GWU UK’s game jam is an effective example of ingenious improvement of worker awareness and strengthening of their bonds - the results of which have the potential to broaden the wider, international trade union movement not only in the realm of software, but hopefully hardware soon, too. That is the level of ambition one can only hope to see more in the broader and ever-widening field of games for purpose. Let’s jam!

-

Hall, Stuart (1981). “Notes on Deconstructing the Popular”. In: People’s History and Socialist Theory. London: Routledge. ↩

Featured in Workers Game Jam (#9)

author

Marijam Didžgalvytė (@marijamdid)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Interview with Colestia

by

Jamie Woodcock,

Colestia

/

June 25, 2019