From the computer to the streets

inquiry

From the computer to the streets

by

Julian Posada

/

June 8, 2019

in

Logout!

(#8)

Voices of a global worker movement

Introduction

From software engineers to factory and gig workers, recent collective action has occurred in all sectors of digital capitalism. In a world in which corporate culture is dominated by an ideology of individualization and business strategies, and production chains remain unfair, exploitative, and unequal, workers have come together, even in instances of extreme alienation, to combat these problems. This article surveys eleven cases of worker mobilizations in the technology sector and platform economy. These cases cover the last two decades and range from North America to Western Europe and Asia. The protagonists are workers from small and big companies, employed or contracted. Their stories represent but a sample of the many collective efforts to improve—or refuse—working conditions under digital capitalism. Yet they offer examples of the rich set of strategies, alliances, and demands that have characterized digital worker uprising.

Foxconn factory workers (China, 1988-ongoing)

“Designed by Apple in California. Assembled in China.” Yet, while Apple easily advertises the design process of its products, its outsourced production system remained largely ignored by the media until the workers who assemble its computers made the news for the wrong reasons. “iSlave” became a term for the mistreatment of the workers that “support” all the coolness and trendiness of the iPhone: multinational companies often ignore—or hide—the extent of their production chain and the living labour that hides behind outsourcing practices. Foxconn, the biggest private employer in China and one of the largest in the world, has specialized since in the creation and assemblage of electronic components, having many of the giants of the technology sector (such as Apple, Amazon, Acer, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft, and Google) as customers. Recently, media outlets and activists have denounced the company’s degrading working conditions, including the physical abuse of workers, excessively long working hours, discrimination, and lack of representation. The overly high levels of accidents and suicides and the working conditions triggered worker mobilizations including a threat to commit mass suicide, a [riot after a worker was beaten by a guard) (https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2207759/2-000-Foxconn-staff-riot-iPhone-5-sweatshop-China-guard-beats-worker.html), and the use of phones to communicate their working conditions. While the working conditions of Foxconn factories remain an issue, the collective voices of workers and the work of journalists have allowed their situation to surface and be known by the public.

Turkopticon (World, 2013-ongoing)

In the 18th-century, an automaton travelled around several European courts beating players at chess. It came as a surprise that, instead of an autonomous machine, in reality, the “Turk”, as it was called, hid a human being inside that manipulated it, creating the illusion of its automation. In recent years, with the advances of artificial intelligence, a similar process of “artificial artificial intelligence” is happening through the labour platform, rightly named, Amazon Mechanical Turk. This is a “micro-work” service by the technology giant Amazon where companies and individuals can hire workers to perform small tasks called “HITs” (Human Intelligence Task), by remaining invisible, as “ghost workers” to the public and even to themselves, preventing the creation of strong ties between workers. Micro-workers are sometimes paid a few cents of a US dollar for each task and are subject of constant evaluation by the platform. Tasks often include content moderation, data labelling, machine learning training, and the correction of AI’s mistakes and limits, sometimes even impersonating machines. In response to the complete lack of voice and the difficulties of organization, since workers are very easily fired and cannot evaluate their employers, the webtool (Turkopticon)[https://turkopticon.ucsd.edu/] was created to rate the requesters of HITs in terms of “generosity”, “communicativity”, “fairness”, and “promptness.” These tools would give workers the possibility of knowing which requesters had fair relationships with them and advising others against accepting tasks with certain requesters. The Turkopticon shows that even in these extreme instances of alienation, workers can still cooperate and contribute to their collective wellbeing.

IBM workers strike on Second Life (Italy, 2007)

MEDIA Video: “IBM Virtual Strike in SECONDLIFE!”

An avatar is haunting IBM: in the heyday of Second Life, the virtual world promised to change everything, from marketing to human communication. For a brief time in 2007, it did provide a chance for workers to ride the hype and organize a virtual strike. It was the main labour union of IBM workers in Italy, with around nine-thousand members among software engineers and other employees, to seize the moment and use Second Life as a platform for their mobilization. The tactical intervention showed workers’ creativity and eventually won the struggle. Pretty much like any self-respecting modern corporation of the time, IBM had invested in establishing a marketing presence in the virtual world, based on a set of islands, buildings, and avatars. When the hundreds of protesting avatars showed up, they disrupted IBM’s virtual operations and made a splash on European media: The first virtual strike in history! is quite a headline indeed. The strike opposed IBM’s reduction of bonuses and refusal to increase salaries despite increasing revenues. Meetings, organizing and training all happened in Second Life, but soon the strike moved IRL: in the days following the Second Life action, workers across Europe picketed management offices and continued with several online meetings, training After the strike, negotiations with the company ended in salary increases. IBM Italy’s CEO eventually resigned.

Global Amazon mobilizations (World 2017-ongoing)

MEDIA: VIDEO GAME The Amazon Race

We are not robots! The quick expansion of Amazon through dozens of fulfillment centers in the Western world and beyond has been met with a transnational wave of unionization, mobilization and strike. Starting in 2015 and accelerating since 2017, and ranging from Poland to Minnesota, workers have been confronting Amazon and reclaiming better salaries, worker control over the extreme flexibility that characterizes warehouse labour, and a reduction of precarity. The warehouses where Amazon stores the commodities that customers buy through its website are distributed in the peripheries of major metropolitan centers. These gigantic distribution centers have come to employ half a million workers worldwide. Amazon workers are acutely aware that in the distribution centre, algorithms and robots dictate the pace of labour, surveil workers, and help management discipline them. Further, Amazon uses a dual employment model: part of the staff is hired under permanent contracts, while a mass of workers contracted through staffing agencies provides a flexible workforce to be expanded and contracted depending on market fluctuations. This generates a specific kind of class composition, with the heavy presence of suburban working class staff as well as migrant labour. Yet neither this complex composition nor Amazon’s notoriously anti-union tactics have prevented the intervention of traditional and independent militant unions, especially in Europe. But there is more. Amazon can quickly reconfigure its network of warehouses, and a strike in France can be bypassed by processing orders in Catalunya or Italy. Workers are aware of such challenges. In response, transnational or regional networks of unions and worker collectives have been trying to take the struggle to the next level.

Food delivery riders (World, 2016-ongoing)

Labour platforms are taking up the streets: riders wearing the images of Deliveroo, Foodora, and UberEats are a commons sight in many cities around the world. These platforms provide a cheap and moderately reliable delivery service to consumers and restaurant owners. But, even when it seems clear that these riders are providing their labour for these companies, they turn a blind eye on their status, considering them as “users” and denying them any social protections that should be guaranteed for workers. Not only these “users” can be fired quickly and don’t have the right to minimum wages, but they are left alone in case of accident and injury. Many of these strikes started in Europe after the unilateral reduction of salaries and payment conditions for workers who didn’t have any say on this and other constant changes in the platforms’ terms and conditions. These changes included, notably, the shift from an hourly wage to a per-delivery payment, which meant that workers wouldn’t be earning money for the time that they spent waiting for orders. Other demands were also eventually included, such as protections in case of an accident and extra wages for weekends and in case of adverse weather conditions. Three of the organizations behind the protests are The Independent Workers Union of Great Britain in the United Kingdom, Le Collectif de livreurs autonomes parisiens in France, and Justice for Foodora Couriers in Canada.

Collective action against ride-hauling platforms (World, 2011-ongoing)

Since the inception of ride-hauling platforms such as Uber and Lyft in the early 2010s, taxicab and Uber drivers began mobilizing against them. Historically, in many jurisdictions, the taxicab sector already presented problems for workers due to the expensive licenses that were often allocated by cities to a handful of wealthy entrepreneurs who, in turn, leased them to drivers. Platform drivers offered the same services without complying with the already existing rules, which caused friction between platform and traditional drivers. The first wave of protests were initiated by taxi drivers who demanded that the company comply with existing jurisdiction regulating taxicabs. With time, platform drivers also organized, demanding in many cases their recognition as employees and the rights that would normally be tied to contractual employment such as minimum wages and even the actual payment of their fees. Platforms, such as Uber, have characterised by playing the different stakeholders, passengers, drivers, and governments against each other on their benefit, according to recent published research by Canadian ethnographer Alex Rosenblat. While, to this date, the outcome of the protests has been diverse (some jurisdictions legalizing Uber or rendering it illegal), the platform has proved its disregard for the rule of law by operating nonetheless in many areas, using its international and online status to ignore any social responsibilities.

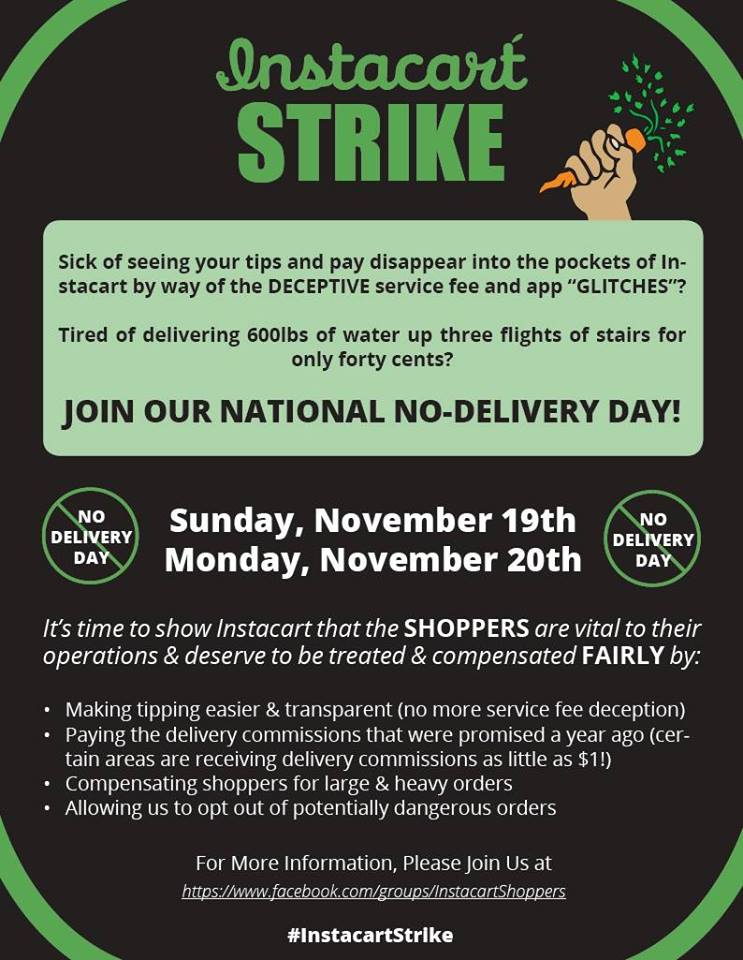

Instacart worker protests (United States, 2016-2018)

Could you carry 10 items from the grocery store to someone’s home as a job? What if the job was paid less than a dollar and would require some… powerlifting? Instacart, a platform that proposes an outsourcing service of grocery delivery, was allegedly paying as low as one US dollar per hour to its workers and was accused of imposing a wage system that did not consider their wellbeing. For instance, since 2016, the platform has been aware of the ability of their workers for collective organization, which lead them to cancel their plans to remove the tip option of their application amid the threat of workers of striking. Later on, the platform placed a limit of items that could be carried by a single courier, but they did not set a limit on weight, so workers ended up moving heavy articles such as up to 270 kilograms of bottled water! Instead of using the company, workers decided to organize a strike through social media to refuse to take any orders for a day in 2017 and once again in 2018.

Engineer protests at Lanetix (United States, 2017-2018)

Like a nightmare story coming from 19th-century rampant laissez-faire capitalism, Lanetix, now called Winmore, fired fourteen engineers after they created a union. Unionization is rare in the technology industry, especially among white-collar workers, so this initiative came after the organization of security officers in major tech companies in a union that resulted in an increase in their salaries. Workers started to organize through an internal communication platform after the startup fired a female engineer and implemented policies that divided employees, especially along gender lines. After being sacked, the company’s engineers and allies protested in front of Lanetix’s offices with flags and banners. After almost a year of the strike and after being fired for having organized the protest, the engineers of Lanetix obtained US$775,000 in compensation from the startup after feeling a complaint and winning their case in court. As the workers said: You can fire a worker, but you can’t fire a movement.

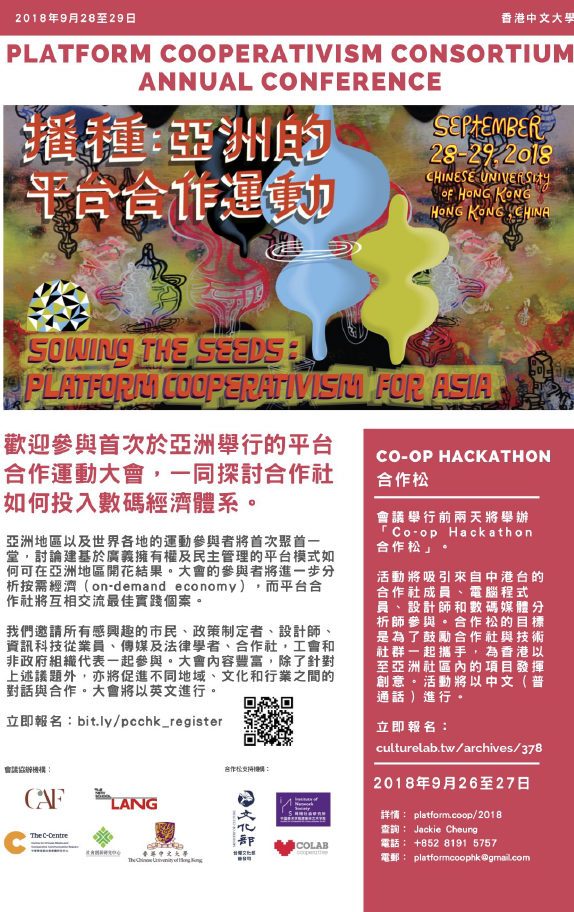

Platform co-op hackathons (China, 2016 & 2018)

In an effort to create digital infrastructures for existing co-operatives in China, two hackathons were organized in Shanghai and Hong Kong where programmers and representatives of co-operatives mainly from Taiwan and China gathered to share ideas and code programs according to the needs of platforms. Different panels were organized into eight teams that discussed projects that including learning, foodbanks, ride hauling, or assisting aboriginal communities. The objective was, for coders, to contribute their knowledge into helping communities develop their own technological infrastructures. For co-operatives, this meant kick starting their projects of becoming digital platforms. According to organizer Huang SunQuan, this exercise not only meant the communication between two social groups, coders and coops, but also an intergenerational bridge, since most coders are young individuals while cooperative members are middle-age or senior. These initiatives allow traditional cooperatives to have access to fundamental knowledge of programming that is usually monopolized by big corporations and allow them to adapt to the rapid changes of the Information Age.

Google Walkout on Sexual Harassment (World, 2018)

On November 1st 2018, thousands of Google employees around the world started a series of walkouts protesting the poor handling of sexual harassment cases in the company. Workers from London, Dublin, Zurich, Berlin, Haifa, Singapore, and Tokyo, as well as in different cities in the United States and Canada, left their office spaces before noon. They left a note on their desks that read “I’m not at my desk because I’m walking out in solidarity with other Googlers and contractors to protest sexual harassment, misconduct, lack of transparency and a workplace culture that’s not working for everyone.” According to the main Twitter account of the campaigners, Google Walkout for Real Change, their demands were ‘an end to forced arbitration’, a ‘commitment to end pay and opportunity inequality’, and a ‘publicly disclosed sexual harassment transparency report.’ Moreover, the workers demanded a ‘clear, uniform, globally inclusive process for reporting sexual misconduct safely and anonymously’ and to ‘elevate the Chief Diversity Officer to answer directly to the CEO […] in addition, appoint an Employee Representative to the Board.’ This collective mobilization, coming from one of the wealthiest corporations of the technology sector, shows that many workers are concern by a change in the digital corporate cultures towards a more inclusive and equitable workplace including not only full-time employees but also contractors.

The unionization of workers in the gaming industry (Canada, United Kingdom, and United States, 2017-ongoing)

Worker organization has reached one of the last untouched zones of the technology industry: the video-game sector. Game Workers Unite, an organization of workers employed in the gaming industry, began as a conversation between colleagues on Discord about their frustrations about their working conditions. These efforts of unionization are important in an industry that has historically been adverse to government intervention and the collectivization of workers, contrary to the libertarian ideology that impregnates much of the sector. Quickly, the Game Workers Unite initiative grew into an international organization that “seeks to connect pro-union activists, exploited workers, and allies across disciplines, classes, and countries in the name of building a unionized game industry.” Today, the organization has more than 800 members in three different countries: Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. In the latter, the organization has achieved official union status. The surge in membership comes in an industry where workers sometimes suffer from long shifts, going to two times the weekly average, payment below the minimum hourly wage, and propensity to burnout situations.

Conclusion

From the centres of one of the biggest technology corporations in the world, to the millions of personal computers of platform workers scattered around the world, the voices of thousands of workers in the tech sector and the platform economy are being heard by the public. While in some cases their concerns are being addressed, in many other cases their struggles are maintained or are even worsen, since they depend on systematic chains of exploitation that are maintained and even reproduced by governments and corporations. The examples of this articles, however, show that there is hope in the cooperation of workers and the involvement of different sectors of society to the improvement of the working quality for all.

Featured in Logout! (#8)

author

Julian Posada

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Technology and The Worker

by

Wendy Liu,

Marijam Didžgalvytė

/

March 30, 2018