Sponge fishers of Hydra - A history

by Ed Emery

April 13, 2019

An oral history of the sponge industry in the island of Hydra, Greece

Sponge fishers of Hydra - A history

by Ed Emery // April 13, 2019

An Oral History of the Sponge Industry in Hydra

Ed Emery [School of Oriental and African Studies – SOAS, London]

[Paper presented at the SOAS Sponges Conference, Island of Hydra, 19-20 May 2018]

SECTIONS:

- The perils of oral history. Methodology.

- Working conditions of the sponge fishers

- Restrictions on the Greek sponge fishing activities

- The production process of sponges

- The sociology of departure

-

Ending our story in the present

-

The perils of oral history

Arriving in the Hydra to do the oral history of the island’s sponge fishing industry, [1] I was told by some people: “There is no point. The old timers are all dead.” But the Greeks do not let their dead depart so easily. Through millennial practices of myth, story-telling and song, the ancestors live on. And it is in that spirit that I have prepared this paper.

With a precautionary note that my local informants are sometimes less than precise, and that, where possible, I have triangulated their information with musical and textual resources.

I take as my starting point a song written by a well-known Rebetiko composer, Dimitris Gogos, also known as “Bayaderas” (1903-85). Born of a father from Poros and a mother from Hydra, his was a particularly sad story. As a musician, during an onstage performance in 1941, he was suddenly struck blind, and there are photographs of him singing around the streets of Athens to make a living. So-called “sfoungára” [“sponging”] – singing in the clubs and passing the hat round. He wrote songs that were popular in the 1940s – not least about the sight of beautiful girls, a moving fact given his blindness. One song in particular – “Psaropoúla” – has become the de facto national anthem of this proud maritime island of Hydra. [2]

The song is remarkable, because it encapsulates a sociology of the sponge-fishing industry that began in the nineteenth century and endured through to its collapse in the 1960s. It is my intention to unpack that song a little

But first let me start with another song, by the great Rebetiko composer Vassilis Tsitsanis. It is a song about the Greek fishing fleets that used to sail to North Africa.

Sto Toúnezi, sti Barbariá,

Sto Toúnezi, sti Barbariá, mas épiase kakokairiá.

Translated: “In Tunisia, in Barbary, a bad storm caught us”. [3]

Immediately we have several elements. First, the extent of the fishing ranges. All around the Mediterranean, but notably along the coast of Tunisia (known also as Barbary, in the old racist connotation of barbarian). One of my informants tells that in North Africa a statue was erected to his uncle, a benefactor resident in the local Greek community. Second – we were hit by storms. Sponge-fishing is dangerous – more of that in a while – but so is seafaring in general. How many Greek seafarers dead over the centuries.

Strangely, one of my informants remembers this song as “We were hit by good weather” (kalokairiá). This accords with the ancient Greek tradition of naming bad things with good names – for instance the Furies become the “Eumenides” (well-wishers).

So, back to Psaropoúla. The song starts “Xékinaei mia psaropoúla, ap’ to yialó” – “A little fishing boat sets off from the seashore. First, “psaropoúla” – a “little” fishing boat. Of course the boats were not large, but here we have a feminine diminutive that is characteristic of the Greek habit of giving diminutive endings for everything for which they have affection. For instance, my musical instrument, an instrument for which Greeks have great fondness, the “baglamá”, from the Turkish word “baglama”, becomes immediately “baglamadháki” – little baglama. And once again – “ap’ tin Ydra tin mikroúla” – from “little” Hydra. Yes, Hydra is a small island, but here the diminutive is affective

So, we have the boat moving off from the seashore. “Ap’ to yialo”. Here it is important to note that the Hydra harbour from which the boats departed was not always a place of big stone jetties where warships, steamships and ferries could moor. Historically, one side of it had a sandy shore, and the boats were pulled up there in a routine that goes back to Homeric times.

[In passing I have to mention that recently the Municipality has banned fishermen from repairing their boats on the little beach at Kamini – a decision that makes me angry, but that’s another story.]

We also need to unpack that word “xekináei” – “sets off”.

The sponge-fishers of Hydra sailed to the North African shore. They would be away for months. Each year they would leave at about Easter time. The sailing date for winter fishing was the Day of the Cross – which is 14 September in the Greek calendar. All of the world’s seafaring communities has its departure rituals. For instance in the British seaport of Hull, women do not accompany the men to the port for farewells. Nor are they allowed to wash a fisherman’s clothes on the day of departure, for the act of plunging clothes in water invokes the symbolism of drowning that person. In Hydra things were done differently. First there was the blessing of the boats. Holy water was brought, and the icon of the Virgin Mary. The water was sprinkled on the icon and on the boats. The men would cross themselves before departure. There would be thing to eat (mezzé) and wine to drink. And there would be dancing around the boats on the seashore. A full and celebratory community ritual to bid the men farewell. We shall return to this later.

The next line is simple: “Kai pigaínei gia sfoungária”. The boat is going fishing for sponges. As such, it attests to the fact that Hydra, during the 19th and part of the 20th century, was a place which sent out sponge-fishing fleets, and where the harvested sponges were treated and trimmed and stored for export to a wide-ranging international market.

To be precise, during the mid-1800s, and for various reasons, Hydra, which had been the basis of the naval fleet that had defeated the Ottoman Empire at sea and which had contributed so much to Greek independence in 1821, was facing crisis. There was economic slump, unemployment among seamen, and the creaming-off of captains into the newly formed Greek navy. Athens and Syros became prominent centres of shipbuilding, and the men of Hydra were more likely to work as carpentering shipbuilders rather than as seafarers.

But from 1863 onwards the situation was redressed. Commentators rightly refer to sponge fever in this period. Hydra occupied third position among the Greek sponge-producing locations (other big producers being Aegina, Symi and Kalymnos), rising to number one when sponge processing plans were set up on the island, and networks of sales outlets were established in Europe. From Hydra each year upwards of one hundred vessels would sail to the North African coast, returning with 60-70 tonnes of sponges out of a Greek total yearly catch of 150 tonnes.

In Hydra itself there were processing facilities – notably the building that is now the Bratsera Hotel, which still preserves internally some of the equipment and (more importantly) the correspondence and accounts ledgers of the old sponge processing company, which attest to the extent of the island’s commercial networks. A precious data resource. We have visited those premises as part of our conference.

- Working conditions of the sponge fishers

The perils of the life of a Greek seaman have been charted graphically and with much poetry since ancient times. Song is no exception. In the words of the Tsitsanis song “Sto Toúnezi…” for instance, we have the phrase “anáthema se thálassa” – a curse on the sea. A very strong statement.

Ανάθεμα, ανάθεμά σε θάλασσα, που κάνεις ώρες-ώρες

να κλαίνε χήρες κι ορφανά και μάνες μαυροφόρες

Στα αγριεμένα κύματα, στη μαύρη αγκαλιά σου

μου πήρες τα παιδάκια μου και τα ’κανες δικά σου

Ανάθεμά σε θάλασσα π’ όλο μάς καταπίνεις

Παίρνεις λεβέντες διαλεχτούς και πίσω δεν τους δίνεις

A curse on the sea – you cause widows and orphans and mothers to weep.

On the wild waves, in your black embrace,

You took my children and made them your own.

A curse on the sea – you who swallow us up entirely.

You take finest young men, and you do not give them back. [4]

However, arguably it was not the sea but the working conditions that did the most damage to the lives of the men of the sea.

We are fortunate in having an eye witness in Theódoros Kriezís, of Hydra and a member of parliament. He was of the family of Admiral Antónios Kriezís of Hydra, who went on to become prime minister of Greece. In 1935 he wrote a comprehensive report on the state of the Greek sponge-fishing industry, which was awarded a prize by the Athens Academy, and was later republished, in 1965-66, in the Hydra newspaper “To Méllon tis Ýdras”, of which Tákis Amourgianós of the Hydra Historical Archive has kindly made me a copy.

We have to consider the general conditions of the sponge fishing boats. Away for months at a time. Crewing on board small boats, where you shared your sleeping space with the air pump and sponge storage and food storage. Long days spent working in the fierce sun of the North African coast – men would return with their skin black and blistered. And most particularly, the dangers of the diving condition known as “the bends” – the release of dissolved gases inside the body in the form of bubbles which cripple a man. In the seaports of the Mediterranean – and Hydra was no exception – there were many men invalided in this way. Old before their time, walking with the aid of walking sticks.

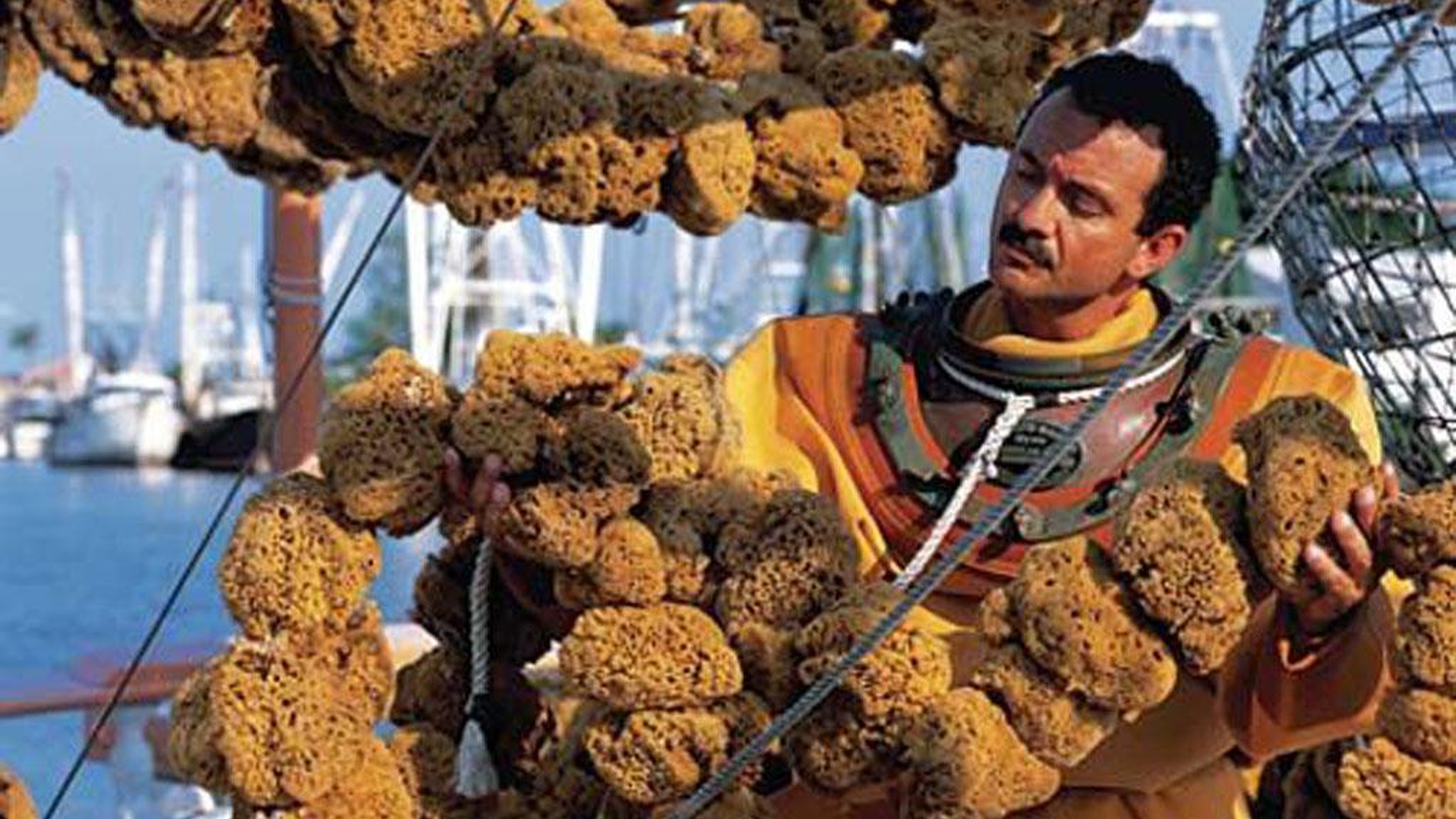

The dangers of decompression sickness became particularly acute when Greek seafarers, as from 1865, introduced the use of the hard-hat “scáfandro” or diving suit.

“The Greek sponge divers introduced the scáfandro en masse, and were able to harvest unprecedented wealth from the depths. This was years before Paul Bert associated decompression sickness (DCS) with gas bubbles, or Haldane published the first decompression tables.

The divers paid a horrific price for their ignorance; in the first 50 years of scáfandro use, some estimates put the toll at 10,000 fatalities among Mediterranean divers.” [5]

The working conditions were such that the Greek parliament was moved to intervene. In 1910, Law 3617 was passed, which set the rules for regulating the industry. In ports the harbourmaster was to make provision for a doctor and an engineer to inspect the equipment of the sponge boats, and to set limits for the depths of diving according to the equipment in hand. It also set aside funds to create two schools for divers – one to be established in Aegina and one in Hydra.

However, as Kriezís tells us, these schools never operated, because of resistance from the divers. A determined effort by the state to intervene in the life of the sponge-fishing community, but it met resistance from that community. His fall-back recommendation, therefore, was that peripatetic trainers should go to the sponge fishing ports at the start of each season, and instruct the divers and the captains in the basic requirements of safety and good practice. Handbooks were to be printed, with copies to be placed on each boat. There is a real question as to whether they would ever have been consulted, let alone the law’s assumption of literacy among seafarers.

The 1910 law also provided that each dive boat had to have a sufficient number of divers to minimise repetitive dives. Captains were obliged to use decompression tables and, in cases of bends, to attempt in-water recompression. Dive boats had to have at least two lead tanks with compressed oxygen for first aid purposes. [6]

I have seen it stated that captains had an interest in looking after their divers because they tended to be paid in advance, and because the state had proposed the institutionalisation of a fund for each outgoing vessel, to pay for eventual death or injury of sponge fishers.

Although the image of a caring state and caring captains is attractive, it also had its bad side. For instance, an unsubstantiated story of a captain who did not want to share his proceeds with a given diver. He decided to turn off the oxygen while the diver was under water. But of course he did not do it himself. He owed money to the man who operated the air pump. So he told the man “You will get your money if you turn off the oxygen.” In this way the captain did not do the murder himself, but passed the responsibility to a subordinate.

For Hydra the position is strange – on the one hand the island produces admirals and politicians (five prime ministers to date); on the other, it is resistant to the state. The structure of the sponge-fishing industry was a case in point. It was a locally-organised community operation, characterised by cooperating kinship networks, and based on shares of the catch being apportioned among the various participants in the production process. Deals would be sealed by handshake and mutual trust rather than by contract. Outside intervention would not be appreciated. In Hydra we have had a similar situation at present, with the local muleteers, who have historically operated as a self-activating entity, and who have regarded with suspicion any external attempts to bring new medical and equine practices into their world. Happily that has now been resolved (in a process in which, incidentally, we have ourselves played a small part).

The state is similarly interested to intervene in monetary matters. Of course the state always wishes to stamp out the cash economy, and impose taxability of incomes – and the islanders are equally resistant to that. But in the case of the sponge divers another logic is in play.

Our informants explain that the departure of the sponge-fishing fleet – at its height, up to a hundred boats – was accompanied by big festivities. Violin and lute players played in the tavernas and a lot of alcohol was consumed. There are reports of pistols being fired at wine barrels to liberate their contents for the pleasure of the general public. All of this – the glénti – lives on in the popular memory.

[Indeed, it is claimed on respectable authority that the custom of throwing the holy cross into the water at the time of Epiphany (6 January) only came about because drunken fishermen were too drunk to carry it, and it ended up in the water.]

However the state (local and national) takes a dim view of all this. Again, here is Kriezís writing in 1935, and commenting on the system of paying the sponge fishers in advance of the boats’ departure:

“It is hopeless to spend thousands [of drachmas] on wine-drinking and the payment of violinists in mindless entertainments, and then, when the sponge boats set off, the families are left with no money in a state of penury.”

He further specifies

“Before the world economic crisis [of the 1930s], when sponges were fetching good prices and the divers’ wages were correspondingly high, more than one hundred violinists came to Hydra for the parties of the sponge divers.” [7]

His proposed method for controlling this situation was a system of payments to divers that operated in the Dodecanese – namely that the sponge fishers’ payment should be staggered over a period of time, so that they cannot spend their money all at once. And, in passing, he notes that there were four systems of payment currently in operation – by the season (winter or summer); per month of work; by merídion (share of the profit); by kopélli (share of the catch).

If proof were needed of the festive habits of the sfoungarádhes, we have an account in the song of the same name by the well-known singer Strátos Payoumtzís.

Οι καημένοι οι σφουγγαράδες, είναι όλοι κουβαρντάδες

Τρώνε όλα τα λεφτά τους, φεύγουν, πάνε στη δουλειά τους

I asked lady in the port the meaning of kouvardádhes. Their eyes lit up. It means a person who is overflowingly generous, who always buys drinks for people, the person who gives the biggest tips. So:

The “poor wretches” of sponge fishers, they are all big spenders.

They spend (metaphor: eat up) all their money.

And then they go away, to do their work.

This verse, by the way, appears to confirm the practice of payment of moneys in advance of departure.

- Restrictions on the Greek sponge fishing activities

After the First World War, Greek sponge-fishing captains found their range of operation increasingly limited. With the fall of the Ottoman Empire – which had previously allowed the Greeks considerable leeway on the seas, not least for the pursuit of pirates – the southern coasts of the Mediterranean fell increasingly under the control of the European imperial powers, who attempted to establish their own control of the sponge markets.

Thus, for instance, the Englishman L. R. Crawshay proposed that sponge fishing around Cyprus should be handed over to an English company as a monopoly. [8]

[Incidentally, Crawshay produced a fine piece of work on the cutting and transplanting of sponge materials, a text which is available online.] [9]

Similarly, the newly established Turkish state sought to ban foreigners from fishing for sponges in their waters. However, an exception was apparently made for Greek captains who would take Turks on board as crew members to teach them the art of sponge-fishing. And in that same spirit it is reported that a Turk came to the Island of Hydra in the early 1930s to learn from the locals.

And of course Kalymnos is only a few miles off the coast of Turkey, so relationships with Turkish fishermen would seem natural.

As regards the range extent of the sponge-fishing campaigns, the Payoumtzis song says:

Φεύγουν για την Ιταλία, Ισπανία, ρε και Γαλλία

In other words, they sail to Italy, Spain and France. [Note: these two latter destinations do not feature in Roberto Pronzato’s map of the present sponge banks of the Mediterranean.]

Of course many factors have combined to decimate the industry and the sponges themselves. Obviously, the onset of plastic sponges from the 1960s onwards has a drastic effect on the market. And also the fact that post-independence North African countries take control of their own waters – and their workers work for lower wages than the Greeks. And the natural-sponge market is furthermore full of sponges coming from the Caribbean – which is likely what you will buy these days in the souvenir shops of Hydra.

And of course the demise of sponge harvesting as a result of massive die-off of Mediterranean sponges. The reasons adduced for this are many – for instance, local fishermen cite radioactive fall-out from the Chernobyl disaster in April 1986, which coincides with the dates of the big Mediterranean disease epidemic in the late 1980s. Or – as recent scientific studies have shown – the fact that some species are particularly susceptible to climate change and the warming of the oceans. This has been the case of Ircinia fasciculata, for instance, in the Western Mediterranean. [10]

There is also the virtual wipe-out of Spongia officinalis, the “sponge by definition”, as reported by Pronzato and Manconi in their paper for this conference. As Pronzato reports in another paper: “The devastating epidemic between 1985 and 1989 has impacted the abundance of Mediterranean sponges,” to the point where harvesting is no longer economically viable. [11]

There is also the case of human greed. As long ago as 1935 Theódoros Kriezís warned that the practice of trawling for sponges – the dragging of nets along the bottom of the sea, suspended from a bar – had to stop because it was destroying life on the seabed. Trawling of sponges (kangávis), he said, had to be banned forever – dia pantos. Personally, he would permit only small fishing by local families, using the kamáki spear hook (or triáini) (not least because the poverty-stricken populations of the seaboard needed ways to earn a living). However in other places trawling continues unabated, with all its consequent ecological disasters. As the FAO reports from North Africa,

“In the 1980’s World sponge production oscillated between 206 and 360 mt. Tunisia used to be the major producer accounting for about half of world production of sponges. In 1986, Tunisia collected some 100 mt. However, production has decreased, due to heavy exploitation and to a disease experienced in summer 1986. Consequently, total production collapsed to only 9 mt in 1988, from the 100 mt normally harvested. Most of the Tunisian sponge production [is] collected by trawlers.” [12]

- The production process of sponges

The sponges are gathered from the seabed and placed in the diver’s apochí (basket). Brought to the surface, the processing of the sponges starts on board. They are washed on a hardwood távla, or board. They are beaten until they give out their inner juices (zoumí). They are then kept for some time in the open air so that they die. Then the sponge is put back into marine water until the black pellicle which covers the sponge can easily be removed. All organic parts not belonging to the skeleton are removed, as also are intrusive materials (small stones etc). In a second period of processing the sponges may be bleached in order to give them the desired yellowish colour. In this later process the sponges are also trimmed into desirable shapes with shears (psalídhi), work which in historical photographs appears to be done by men. They are then pressed and packed into sacks and crates for storage or shipping. In processing plants, screw-presses may be employed; elsewhere the men tread the sponges into the sacks. The leftover offcuts of the sponges are used for a multiplicity of purposes.

- The sociology of departure

It should be said that the opening phrase of the song, “xekináei gia sfoungária” (“it is setting off for sponges”), covers a mighty multitude of activities that have to be done prior to departure. For instance, the sponge boats have to be provisioned. In the USA, reports speak of Greek sponge fishers setting off with large quantities of spaghetti, olive oil and tomato paste, plus two hundred pounds of onions and a hundred pounds of garlic. [13] In Hydra, the speciality was kavourmá (a word of Turkish origin) – namely chunks of beef which were part-cooked and then packed into clay pots (ghástra) together with fat that would preserve them through the months ahead. Good meat, not just any old meat. Known as kréas tis stámnas, “jar meat”, these meats could later be cooked slowly in the pots, and then the pots broken and the meat eaten. They also had hard-tack bread, which would not rot, known as galétas or psirópsomi, flat ship’s biscuits with holes in. For the baking process pine wood was gathered (ghdhénia), which gave a pine flavour to the bread. One of the island’s present hotels, El Greco, was a former ships-biscuit factory. For fruit they took kydhóni (quince), stafíli (raisins), kourmádhes (special olives that can be eaten straight from the tree), and phoenikadhes (dates). And of course water and wine.

My informants, in memory, give an image of appetising culinary variety. But more often the reality was hard-tack, and the meals were eaten once a day when the work was done. So says the “Sfoungarádhes” (“Sponge fishers”) song of Yórgos Bátis, as sung by Strátos Payoumtzís:

Και το βράδυ ρε που σχολάνε την ξερή γαλέτα αρπάνε

κάθουνται και τη μασάνε κι ύστερα για ξάπλα πάνε

In the evening they take their dried galétas, and they sit and

chew them, and then they go to bed. [14]

It goes without saying that these foodstuffs were prepared by the womenfolk of the island, who were thus enrolled as an integral part of the sponge-producing industry.

In the instances where a bratséra mother ship (also known as depósita) accompanied a number of smaller kaíkia, the foodstuffs would be carried on board the bratséra (which, incidentally, could also carry the smaller spear-fishing boats needed in the fishing ranges).

Doctor Thódoros A. Sachtoúris writes as follows:

Whole fleets, with machinery [diving suits], with gagáves, with divers, with kamákia, set off from Hydra, accompanied by the icon of the Madonna of the Monastery, with flags, with bells ringing, and with the sound of cannons.

And when they returned they were similarly welcomed with bells and cannon fire, and they brought large quantities of sponges, which were sold at good prices. The money flowed out, the taxes arrived at 24%, the residents stopped, and moved to Athens and Piraeus. People from Kalymnos and Simos came and lived in Hydra. The abandoned and half ruined houses were restored, were set up again, and were lived in by well travelled residents. The trading shops set up workshops, and wine selling, the most fortunate being the taverna of the widow above, and the taverna of the widow below, honour be to them.Gunfire rang out day and night all over the island. Violin players were welcomed, and hundred drachma notes would be stuck to their foreheads, and in their enthusiasm the assembled public opened even the pyro of the barrel for the wine to pour. [15]

So now let’s go back to the song. The final verse constitutes the sociology of the crews that set off on the sponge-fishing boats. Leaving aside the fact that the verse is a little hard to sing, it tells us

Έχει συμιανούς, καλύμνιους απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

Έχει υδραίους και ποριώτες, αιγινήτες και σπετσιώτες

In other words: it has men from Symi and Kalymnos, from Hydra and Poros, and Aegina and Spetses.

It won’t escape your notice that some of the places named are noted locations of sponge-fishing activity – Symi, Kalymnos, Aegina. The question is, why does the song gather them all together in a boat that is sailing from Hydra? One reason is given in the quotation above: in the glory years, Hydra pulled ahead as the main sponge-fishing in Greece. So people came from other islands to live here.

One wonders – although I have no evidence for this – whether people from other locations might have had particular skills required in the industry. A boat requires personnel who can dive, who can captain a vessel, who can maintain an engine, who can perhaps do marine woodworking, who can operate an air-pump, who can properly fit a diver’s helmet, and maybe also who can cook. This would be a matter for further exploration.

Finally, the song concludes: “Pou eínai oli pallikária” – “Who are all strong young heroes”. There is no doubt that the sponge divers were held in great respect for the tough lives that they endured. The disabled among them also won recognition, as in the case of Kalymnos, where there is now a local tradition of a dance called “michanikós” (“mechanical”, referring to suited divers), in which one of the dancers dances as a sponge fisher crippled by the bends. [16] It is a moving testimony to a historic past, expressed through dance. We shall view the film tomorrow.

- We end our story in the present – or perhaps in a future

One of our conference participants wished to go snorkelling in the waters of Hydra. He wanted to know if there were any sponges to be seen. Locals assured him: No sponges in Hydra… all died out in the early 1950s… no more kaíkia… Maybe he would find one or two of the common black ones, but nothing of note… And indeed, as he reports, he found little of note. The local waters of Hydra have been subjected to the same desertification that affects other shorelines of the Mediterranean.

However, one of our informant recalls that, when he was a boy in the 1980s, there was a man who had a little kaíki in the harbour. He would sail out, fish for sponges, bring them back, and process them in the harbour next to his boat, and then sell them. This suggests that the local industry did not die entirely in the 1950-60s.

He also recalled another local man who would procure low-grade off-cuts of real sponge and trim and dress them in such a way that they looked like the proper thing and could be sold to tourists as such. This, we are assured, was because he wanted to keep the image of the island’s sponge-fishing tradition alive in people’s minds.

It is improbable that the glory days of Hydra sponge fishing will ever return. However there is arguably a case for willing hands to work towards a restoration of the island’s marine fauna. Worldwide there are several examples of this kind of marine remediation work – the Florida Sea Grant replanting project being a case in point. [17] This will be the subject of a future paper.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Takis Amourgianos, Kostas Argitis, Lakis Christidis, Panayiotis Vlahopoulos, Jason Melissinos, and the late Yiannis Karamitsos.

NOTES

-

Terminological dilemmas. Sponging is an extractive industry and should be subject to analytic guidelines established for other global extractive industries. “Fishing” and “harvesting” are common usages, with reference to sponges. The latter seems more appropriate, but the technologies used resemble those of the former. However the agrarian aspect needs to be set alongside the clearly present aspect of “hunting”, as evidenced in the Greek song Ο Σφουγγαράς [A. Sakellariou], which says “σφουγγάρια για να κυνηγώ” – “I hunt sponges”.

See: https://youtu.be/woBHpGnMXYE -

“Psaropoúla: as sung by Sotiria Bellou

www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgalQ6v-ByM - “Sto Toúnezi, sti Barbariá”: as sung by Anna Chrysafi, Vassilis Tsitsanis, Mairi Linda and Thanasis Yannopoulos.

www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOdt0h0Xkio - “Anáthema se thálassa” = “Sto Tounezi…” in Note 2.

- Dangers of diving: www.alertdiver.com/The_Story_of_Sponge_Divers

- Theódoros Kriezís, Η Σπογγαλεία [The Sponge Industry], To Méllon tis Ýdras, September 1965 seq., Part 3, p. 245.

- Kriézis, ibid. Part 4, p. 13.

- Kriézis, ibid. Part 2, p. 217.

- L. R. Crawshay: Studies in the Market Sponges I. Growth from the Planted Cutting, Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, Volume 23, Issue 2 , May 1939, pp. 553-74

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-the-marine-biological-association-of-the-united-kingdom/article/studies-in-the-market-sponges-i-growth-from-the-planted-cutting/457E2371015F4F94189FCE5E31376626 - Ircinia fasciculata: See: Despoina Konstantinou, Vasilis Gerovasileiou, Eleni Voultsiadou, Spyros Gkelis, “Sponges-Cyanobacteria associations: Global diversity overview and new data from the Eastern Mediterranean”

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0195001 - Roberto Pronzato and Renata Manconi, “Mediterranean commercial sponges: over 5,000 years of natural history and cultural heritage”,

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1439-0485.2008.00235.x - FAO Report: http://www.fao.org/docrep/field/003/AC286E/AC286E02.htm

- “Greek Sponge Divers of Tarpon Springs Florida” [1932] [9’43”]

www.youtube.com/watch?v=bR68ZqgLKzc - Strátos Payoumtzís - Οι σφουγγαράδες [Oi sfoungaradhes]: [3’08”]

www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWRidwFo_i8 - Theódoros Sachtoúris, quoted in Yiánnis A. Karamítsos “On the sponge industry of Hydra” [in Greek; my translation], in Hydra, Nisos enteles dryopon, Ekdosi Dimou Hydraion, Hydra, 1998.

- “Mechanikos” : The sponge diver’s dance from Kalymnos [4’18”]

www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFYKjCMLT4Y - Jim Cantonis – Florida Sea Grant

www.youtube.com/watch?v=RtB-qTXnjZI

E-mail: [email protected]

APPENDIX 1

Xékina mia psaropoúla [1947]

Music and lyrics: Dimitris Gongos (Bayaderas)

Ξεκινά μια ψαροπούλα απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

ξεκινά μια ψαροπούλα απ’ την Ύδρα τη μικρούλα

και πηγαίνει για σφουγγάρια, όλο γιαλό, όλο γιαλό

Έχει μέσα παλικάρια απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

έχει μέσα παλικάρια, που βουτάνε για σφουγγάρια

γιούσερ και μαργαριτάρια, απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

Γεια-χαρά σας παλικάρια, και στο καλό, και στο καλό

γεια-χαρά σας παλικάρια, να μάς φέρετε σφουγγάρια

γιούσερ κι όμορφα κοράλλια, απ’ το γιαλό

Έχει συμιανούς, καλύμνιους απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

Έχει υδραίους και ποριώτες, αιγινήτες και σπετσιώτες

που ’ναι όλοι παλικάρια απ’ το γιαλό, απ’ το γιαλό

Translation

A fishing boat sets sail, from the shore, from the shore.

A fishing boat sets off from little Hydra,

And it’s going for sponges, all along the shore.

On board it has young lads, from the shore, from the shore.

And the young lads will dive

For sponges and black coral and fine corals, on the shore

Here’s a health to you, lads, and good luck too.

A health to you, and may you bring us sponges, and black coral,

And fine corals and pearls, from the shore.

On board it has lads from Hydra and Poros,

And Symi and Kalymnos, and Aegina and Spetses,

And they’re all good strong lads, on the shore.

YouTube clip, as sung by Sotiria Bellou:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=UgalQ6v-ByM

APPENDIX 2

Sto Toúnezi, sti Barbariá [1953]

Music: Vassilis Tsitsanis

Lyrics: Eutychia Papayiannopoulou

Chorus: Ανάθεμα σε θάλασσα

που κάνεις ώρες ώρες

να κλαίνε χήρες κι ορφανά

και μάνες μαυροφόρες

Στο Τούνεζι, στη Μπαρμπαριά,

μας έπιασε κακοκαιριά

Στα αγριεμένα κύματα

στη μαύρη αγκαλιά σου

του κόσμου πήρες

τα παιδιά και τα `κανες δικά σου

Στο Τούνεζι, στη Μπαρμπαριά,

μας έπιασε κακοκαιριά

Αναθεμά σε θάλασσα

κανένα δεν αφήνεις

λεβέντες παίρνεις διαλεχτούς

και πίσω δεν τους δίνεις

Στο Τούνεζι, στη Μπαρμπαριά,

μας έπιασε κακοκαιριά

Ανάθεμα σε θάλασσα

που κάνεις ώρες ώρες

να κλαίνε χήρες κι ορφανά

και μάνες μαυροφόρες

Στο Τούνεζι, στη Μπαρμπαριά,

μας έπιασε κακοκαιριά.

Translation:

A curse on the sea – you who, for hours and hours,

Cause widows and orphans and black-clothed mothers to weep.

Chorus:

In Tunisia, in Barbary, we were caught by bad weather.

On the wild waves, in your black embrace,

You took the world’s children and made them your own.

A curse on the sea – you who swallow us up entirely.

[Alternative line: You do not spare anybody]

You take finest young men, and you do not give them back.

YouTube clip, as sung by Anna Chrysafi, Vassilis Tsitsanis, Mairi Linda and Thanasis Yannopoulos:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOdt0h0Xkio

APPENDIX 3:

Oi sfoungarádhes [1935]

Music and lyrics: Yórgos Bátis

Οι καημένοι οι σφουγγαράδες

είναι όλοι κουβαρντάδες

Τρώνε όλα τα λεφτά τους

φεύγουν, πάνε στη δουλειά τους

Φεύγουν για την Ιταλία

Ισπανία, ρε και Γαλλία

Σ’ ένα φόρεμα τους βάζουν

πέφτουν και σφουγγάρια βγάζουν

Και το βράδυ ρε που σχολάνε

την ξερή γαλέτα αρπάνε

κάθουνται και τη μασάνε

κι ύστερα για ξάπλα πάνε

Το πρωί που θα ξυπνήσουν

πάλι τις βουτιές θ’ αρχίσουν

Κι αν δε βγάλουνε σφουγγάρια

θα ‘χουν άσχημα χαμπάρια

Translation:

The poor sponge divers

Are all big-spenders.

They eat [spend] all their money,

And then they leave, and go to their work.

They leave for Italy,

To Spain, friend, and to France.

They put them in a diving suit

And they fall [into the sea] and bring out sponges.

And in the evening when they are relaxing,

They take their dry biscuit [galetas].

They sit and they chew it,

and later they go and lay down to sleep.

In the morning when they wake up,

Again they start with their dives.

And if they don’t bring up sponges,

They’ll be in big trouble.

YouTube clip, as sung by Stratos Payoumtzis:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=xWRidwFo_i8

author

Ed Emery

other posts