"They're watching you; don't let them down": the 1985 anti-apartheid occupation movement at Berkeley

by

Left in the Bay (@leftinthebay)

April 28, 2024

Todays pro-Palestinian student organizing bears a striking resemblance to the mid-1980s movement for university divestment from apartheid South Africa.

theory

"They're watching you; don't let them down": the 1985 anti-apartheid occupation movement at Berkeley

by

Left in the Bay

/

April 28, 2024

Todays pro-Palestinian student organizing bears a striking resemblance to the mid-1980s movement for university divestment from apartheid South Africa.

This week marks the thirtieth anniversary of the 1994 election that brought Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress to power in South Africa, generally regarded as marking the end of apartheid. The system of racial segregation and white minority rule was codified after the National Party’s rise to power in 1948, the same year more than 700,000 Palestinians were driven from their homes in the ethnic cleansing known as the Nakba. “Our freedom is incomplete,” Mandela remarked three years after the fall of apartheid, “without the freedom of the Palestinians.”

Outraged by the president’s unshakable economic and military support for a brutal and openly racist regime abroad, student activists across the United States demand their universities divest from that regime. After struggling on for years with only a handful of victories, the divestment movement grows rapidly after that regime declares a state of emergency amid escalating violence between itself and the people under its rule. Students demanding divestment set up a militant protest encampment at Columbia University, inspiring similar camps at other universities. These protest camps are met with massively disproportionate police responses, triggering an explosion of campus occupations across the country. The year is 1985; the regime is apartheid South Africa.

“Soweto’s gonna happen here too”

The first efforts to pressure American universities to divest from apartheid South Africa began as early as the mid-1960s. Overshadowed by the movement against the Vietnam War, these campaigns made little headway. In 1976, the Soweto Uprising pushed the issue to center stage, as over 10,000 Black high school students in the South African township revolted against white rule. Soweto inspired a global wave of solidarity against apartheid, reinvigorating the divestment movement in the United States.

Mass sit-ins quickly became the movement’s favored tactic. In April 1977, Hampshire College students scored the country’s first university divestment victory after a relatively quiet 3-day occupation of the college’s administrative offices. The next month, 294 Stanford students were arrested for occupying the Old Student Union building, which they held for five hours. Directly inspired by their peers at Stanford, students across California formed Campuses United Against Apartheid. They sat-in at a handful of schools in the following weeks; 20 were arrested at UC Davis, 58 at Berkeley, and 419 at UC Santa Cruz. Although at least two more campuses managed to force their administrations to divest – University of Minnesota and University of Wisconsin, where students were teargassed trying to enter a regents meeting – the early 1980s saw an ebb in the student anti-apartheid movement. By the fall of 1984, Berkeley divestment organizers were barely able to mobilize 50 people to a protest on Sproul Plaza, which was dwarfed by a poetry event scheduled for the same day (a sympathetic Allen Ginsberg crossed the line between the two events, briefly carrying a pro-divestment sign).

Around the same time as the Campuses United Against Apartheid sit-ins, radical longshoremen in Local 10 of the International Longshoremen’s & Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU) formed the Southern Africa Liberation Support Committee (SALSC). Also inspired by the bravery of the Soweto students, the SALSC organized targeted boycotts of South African cargo in the Bay Area and shipped donated goods to Tanzania and Mozambique for anti-colonial liberation fighters from across Southern Africa.

Becoming ungovernable

In the mid-1980s, Black South Africans resolved to make their townships “ungovernable.” As resistance, often violent, exploded across the country, the Bay Area anti-apartheid solidarity movement got a jump-start from organized labor. In November 1984, urged on by their fellow workers in the SALSC, Local 10 longshoremen refused to unload South African steel, glass, and other goods from the cargo ship Nedlloyd Kimberly, which had docked at San Francisco’s Pier 80. One longshoreman told the Oakland Tribune that unloading South African cargo would be akin to “not saying anything about the 6 million jews killed in the Holocaust.” Although the boycott was unsanctioned by the union’s international leadership, the workers held out for eleven days. They finally unloaded the cargo after a federal injunction declared the action illegal and threatened local leadership with jail time.

Three days after the longshoremen resumed work, their supporters organized a rally that drew 450 demonstrators to Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza, nine times the number that came out in November. Socialist mayor Gus Newport, a former member of Malcolm X’s Organization of Afro-American Unity, encouraged the students to engage in civil disobedience. The ILWU’s Howard Taylor earned the event’s largest cheer when he declared that his union should have disobeyed the federal injunction. The students marched to University Hall, where a brief sit-in ended with three dozen arrests. Beginning to feel the pressure, UC Regents announced they would review the university’s South Africa investments, not at their next meeting, but at their summer meeting.

That spring, students on the East Coast revived the occupation tactic in a big way. Immediately after a four-day occupation at Amherst ended with the university caving to student demands, Columbia organizers established their own occupation where, in a major escalation, they chained the door to their administration building shut. On April 10th, 1985, the UC Divestment Committee held the first of what became daily demonstrations on Sproul Plaza. After the rally a handful of demonstrators, inspired by the example of Columbia students who had been holding their ground for a week, simply decided not to leave. Their occupation, which quickly grew in size, lasted six days before police raided it on April 16th, making 156 arrests. Later that day, the campus swelled with protesters, among them hundreds of ILWU longshoremen who came out in solidarity with the students. A gray-haired Mario Savio, icon of the 1964 Free Speech Movement, addressed the crowd: “Berkeley students have a tradition of resistance to racism and a tradition of honest rebellion. I encourage you to honor your tradition.” Defiant students restarted the occupation of “Steve Biko Plaza” and declared a student strike for the following day. About 10,000 Berkeley students participated in the strike.

This time, the occupations caught like wildfire. Before the month was out, Columbia and Berkeley were joined by anti-apartheid encampments at Harvard, Rutgers, Cornell, Syracuse, Princeton, Tufts, Stanford, Indiana University, Boston College, University of Florida, UC Santa Cruz, UC Davis, UC Santa Barbara, UC San Diego, UCLA, and more. Students in Wisconsin occupied the state capitol. Solidarity inspired solidarity. Berkeley faculty formed a group, UC Faculty for Full Divestment, to contribute to the movement, and 38 of them were arrested for blocking the entrance to University Hall. Campus trade unions, including an AFSCME local, organized sit-ins. They, too, were arrested. After months of activity and nearly 1,000 arrests (among them People’s Park founder Michael Delacour, Mayor Gus Newport, Angela Davis, and Whoopi Goldberg), the occupation faded out with the ending of the school year. Having only made an offer to “selectively divest,” the regents hoped they had waited out the movement like they had in 1977.

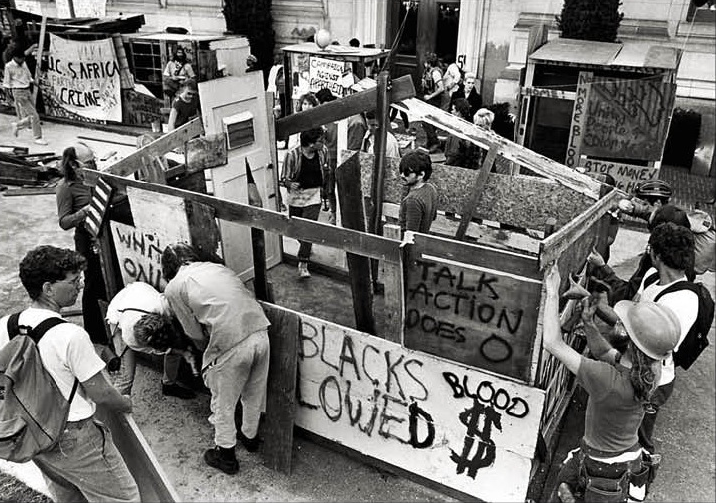

Shantytown

When the students returned in fall, it was unclear if the movement would return with them. Although one student group organized a direct action at Berkeley resulting in 138 arrests in November, the cries for divestment were relatively muted until the spring. On March 31, 1986, a thousand students rallied on Sproul Plaza. Protesters built “shanties” out of plywood and cardboard, intended both to demonstrate the living conditions of Black South Africans and to serve as makeshift tents. Sproul was Biko Plaza again, and the occupation was back. Police raided the camp that night, destroying the shanties and arresting 61 occupiers. This time, though, the students fought back. Cops were pelted with rocks and eggs as they moved in on the camp; police vehicles had their windows busted out. The next day the shanties were rebuilt and, just as quickly, police raided them again. Emboldened by the previous night, students put up a fierce resistance. In the heaviest street fighting Berkeley had seen since the anti-Vietnam War movement, demonstrators constructed barricades and threw bottles at the oncoming police, refusing to be carted out of the shantytown peacefully. The San Francisco Examiner described a chaotic scene, noting that a number of officers had to be physically restrained from violence by other officers. 18 police and 11 occupiers were reported injured. At least two arrested demonstrators were alleged to have homemade incendiary devices. A photojournalist was beaten so badly that a head wound, cut to the bone, required 13 stitches. “I don’t remember anything except I was following along the police and protesters and photographing,” he told reporters, “The next thing I knew, I was lying on the ground with blood splattering out of my head.”

While the chancellor blamed “outside agitators,” outraged graduate students organized a student strike for the next Monday. Around 80% of students were estimated to have skipped class, many with encouragement from their professors. As the month went on, more UC campuses saw clashes between demonstrators and police, as students put up increasing resistance to being arrested. At UCLA, students blocked police vans after a scuffle injured three officers. Students who happened to be passing by joined the fray on the side of the demonstrators, throwing books at police. The assistant vice chancellor for public affairs claimed students threw “everything that wasn’t nailed down,” at the police. “They were even tearing tables and chairs apart.” As the school year drew to a close, the situation was no longer tenable.

On July 18th, 1986, the UC Regents met in Santa Cruz and voted to divest the $3.1 billion it had invested in South Africa-related stocks and bonds, the largest campus divestment of the anti-apartheid movement. Governor George Deukmejian, who had vetoed a state divestment bill just one year earlier, told reporters, “Naturally, I’m very pleased with the outcome.” By the time apartheid fell in the early 1990s, almost 200 educational institutions had divested from South Africa, along with numerous municipalities, including San Francisco, Oakland, Berkeley, and San Jose.

As students and workers mobilize against their institutions’ financial support for the genocide in Gaza, they’re rediscovering both the important role played by American universities in weapons research and development and the potential of exploiting their own strategic location to disrupt those processes. The echoes of the 1985 divestment movement in our current moment are striking. Among the many lessons students and workers can learn from that movement is this: Yes, it can be done.

Some potential lessons for today’s student organizers:

1. Their best weapons are guns and money; ours are solidarity and courage

Divestment at the University of California would never have been achieved without the participation and leadership of organized labor, especially left-wing rank-and-file caucuses. From the militants of ILWU Locals 6 and 10, who kickstarted the movement by refusing to handle South African cargo, to campus staff unions and organized graduate students and faculty, workers’ power to bring large, complex institutions to a screeching halt was key. Just as key was the Berkeley students’ refusal to settle for anything less than full divestment. Rather than allow themselves to be demobilized by lengthy negotiations or co-opted by progressive politicians and other would-be leaders, they maintained a strategy of maximal disruption, making the status quo untenable in service of a single, invariant demand.

2. Don’t get too discouraged by failures and setbacks; struggle comes in waves

The movement to divest from apartheid South Africa developed slowly. Between the 1960s and the late 1980s, it peaked and petered out multiple times. At the time, many participants experienced the low points in struggle as defeats. But it’s clear in hindsight that, while the Stanford and UC sit-ins of the late 1970s may not have been immediate successes, they can’t be called failures either. There’s no telling what the work you do now is setting the stage for later. Don’t be seduced by arguments that “change comes gradually,” but remember that social movements are long-term projects.

3. Tune out the wisdom of the naysayers; they are a historical constant

Despite the nearly universal celebration of the movement against apartheid today, pro-apartheid (and anti-anti-apartheid) views were widespread and often dominant at the time. Berkeley activists faced opposition from their peers, as fraternities repeatedly vandalized the Biko Plaza shanties. Opinion columns in local papers railed against anti-apartheid students, mocking their interest in the suffering of far-away South Africans. “What about North Richmond? What about parts of Pittsburg? Howard Street? These protesters are an insult to all the poor people around them who need help,” declared one representative sample. Letters-to-the-editor pages were filled with missives accusing students of meddling in foreign politics too complex for them to understand. Some cited the horrors of life in the countries already liberated from white rule: “Remember Rhodesia? Of 240,000 whites, 70 percent have left and the exodus continues… South Africans have no desire to experience the Rhodesian saga. They know what will happen to them under black rule.” Others explained that, while sympathetic to the anti-apartheid movement, its methods did more harm than good: “Removing money from the South African economy is dangerous. More blacks will be unemployed and will riot… That country cannot be governed from the dorms of Berkeley.”

4. Build for the long term; search out what’s already been built

One of the striking features of the anti-apartheid movement in the Bay Area is the active participation, not just of veterans of prior social movements, but of institutions forged by earlier struggles. The ILWU, which formed the backbone of the anti-apartheid labor movement, came out of the great San Francisco General Strike of 1934, when radical waterfront workers, many of whom were communists, led a strike that grew to encompass the whole city (in recent years, the ILWU has occasionally refused to handle Israeli cargo). Berkeley mayor Gus Newport, a reliable ally of the students, was a member of Berkeley Citizens Action, a left-progressive political group that grew out of the April Coalition, an attempt by 1960s Berkeley radicals to wield local state power. Many of the students who faced charges stemming from their arrests were represented by Dan Siegel, a one-time ‘60s radical who made the famous speech urging students to “take the park” during the People’s Park movement. While these institutions were (and are) often highly compromised, and were certainly not outwardly revolutionary, they formed a social movement ecosystem that organizers could mobilize towards radical goals. Participants in contemporary movements should think about what kinds of institutions they’re building that can intervene strategically in future struggles.

It’s your turn to teach.

This article is also available as a PDF that can be downloaded and printed as a zine. Download the PDF here

author

Left in the Bay (@leftinthebay)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next