The Difficulties of Working and Unionising in Human Rights Law Practice

by

Louise Lorde

May 12, 2025

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

The challenges and opportunities

inquiry

The Difficulties of Working and Unionising in Human Rights Law Practice

by

Louise Lorde

/

May 12, 2025

in

Legal Workers Inquiry

(Book)

The challenges and opportunities

I am a human rights solicitor. I help people to bring cases against the state. In practice, I have a lot of clients and work on multiple cases at any one time. I try to achieve a good outcome for all of my clients, which can include compensation and an apology. Sometimes, we do not achieve a positive outcome. This can be disappointing and unfair, particularly when clients cannot pursue their case further due to a lack of funding/insurance. It can, however, still mean a lot for clients to have someone in their corner that believes in them, and fights for them to seek some type of accountability/justice

For new cases that I have taken on, I need to meet the client to take their instructions about what has happened to them and what they hope to achieve in litigation. I also advise them about what they can bring a claim for and about the civil litigation process in general. I also need to set up funding for the client’s case. Most of my clients’ cases are funded by legal aid funding, which is governed by the Legal Aid Agency. Due to the stringent eligibility requirements attached to successfully receiving legal aid, I act for a lot of clients on a Conditional Fee Agreement (CFA), which means we do not get paid if we do not settle their cases. If we need to ‘issue’, i.e. to formally commence court proceedings, under a CFA but are unable to get any insurance to protect the client from potentially paying the defendant’s costs if they lose their case, I would consider advising a client to discontinue their case. Insurance is really tricky and almost impossible to obtain in human rights type cases. This is really unfair, particularly in light of the huge amount of resources at the state’s disposal to defend these claims.

Skills

At the beginning of a case, I need to gather as much evidence as possible to prove my client’s case. This involves requesting medical records, CCTV footage, police/prison records and so on. I take statements from the client and any witnesses of/in support of the incident. Once I have secured this evidence, I begin writing a letter of claim, which is generally our first opportunity to set out the facts of our client’s case and why we think the defendant is liable. The defendant then has an opportunity to formally respond. They rarely admit liability to the client’s claim, but they may still agree to enter into settlement discussions if the evidence is strong. Usually, defendants robustly defend the claim and the next step in proceedings is to issue court proceedings.

Sometimes, we need to instruct an expert to document the injury that a client has suffered arising from the incident, such as a psychiatric injury. In order to instruct an expert, I need to review the client’s medical records and write a detailed letter of instruction to the expert to examine the client and confirm what, if any, condition they have suffered and the client’s likely prognosis and potential course of treatment. I then need to carefully consider the draft report to ensure it is written clearly and correctly. This involves cross-referencing the report with the client’s instructions and records because we need our client’s case to be 100% accurate, otherwise the defendant will highlight the inconsistencies in our client’s case that might have a detrimental impact on the likelihood of success.

Once a case is issued, I have to follow a series of steps with strict deadlines to trial. This includes instructing a barrister to prepare a document called particulars of claim, which formally sets out the case that we will run to trial, exchanging disclosure (documents relating to the case) and witness/expert evidence, and then preparing for trial.

Unlike in criminal or family law, I do not advocate my client’s case in court. As a solicitor in my field, I am the person preparing the case, whilst a barrister will argue the case in court. Once a case has been issued, a barrister is likely to be involved. However, we often do not instruct barristers because we settle a case without needing to issue court proceedings

I therefore have a more hands on contact with my clients, compared to barristers. I speak to my clients regularly, taking their instructions and advising them throughout their case. Often that means acting less like a solicitor and more like a support worker or counsellor. I generally have a very close bond with many of my clients.

People often say that you need soft skills to be a solicitor, which people can be quite snobby about or think they’re less important than strong advocacy skills. But they’re really invaluable skills in the legal profession. It’s really important that clients are listened to and heard, and to properly be part of the case they’re pursuing. I don’t know if it is necessarily a good outcome if a client’s case settles, but they didn’t feel heard in the process. This means that the solicitor’s role is important because we are the client’s first point of contact throughout their case and the responsibility generally falls on us to take the client’s instructions and ensure they understand our advice.

Class composition

Another important distinction between barristers and solicitors is our socio-economic backgrounds. In my view, barristers are more likely to be privately educated, attended Oxbridge, and so on. If you look at any of the top human rights chambers, not only are the barristers from very elite backgrounds, they’re also top of their class. They are the elite of the elite. There is only one way to become a barrister, through a pupillage. However, there are quite a lot of different ways to become a solicitor or an equivalent role such as a caseworker or chartered legal executive.

I did an undergraduate degree in law, before completing the LPC part-time, while I worked in another job full time. The reason that I was able to become a solicitor was because I secured a job in the most junior position in admin, before securing a job as a paralegal, and gained the relevant work experience that enabled me to secure a training contract to then qualify as a solicitor. Some people secure training contracts without working in a law firm beforehand, which I think often comes down to class and education. This route has changed recently with the SQE.

Overall, I think my colleagues are from more varied backgrounds compared to barristers chambers. However, in my department, it is still quite an elitist team with a significant number of my colleagues having attended private school and/or Oxbridge. I’m from a working class background and hadn’t met anyone who was privately educated until I moved to London and then all of a sudden I am studying and working with people that felt very alien to me because of their familial wealth and exceptional education background. Generally, the more junior workers in a law firm are more likely to be from a working class and/or racialized compared to the more senior positions who are often white, male and posh.

Relationship with clients and other colleagues

In many ways, I feel very connected with my clients. Even if there are key differences to our background, I often feel connected to them due to our shared vulnerabilities. What brought me to the law was having to advocate for myself when I was young and being let down by numerous state officials. I find it easy to relate to people and making that connection is important. A lot of lawyers keep a distance and think that they could never be in that situation. But anyone can come to harm or be let down by the state. I often feel like that could easily be me or a family member. That is what drives me to fight hard for my clients. It’s part of the reason why so many of us work way outside of our contracted hours; we really care about our clients and want to help them achieve some form of accountability/justice. We might be one of the only people who has sincerely believed what they’ve said and will try to do something about it.

Currently, I work quite closely with a senior solicitor and we’re part of a team. In a law firm, you’re meant to have monthly supervision meetings for management. Usually this involves some questions about how you are doing, how is the volume and type of work, whether there are any problem files, and perhaps any notable settlements or awards. It can be quite tricky, because it’s up to you to explain if you are suffering and that means being able to express that, which is difficult due to the stigma associated to mental health. I think partners don’t appreciate the pressures that most people in London face because they probably own their home and don’t have to worry about landlords, house shares or extortionate rents.

I remember when I was a paralegal, I really struggled and had a lot of self doubt. I found it hard doing this work when I wasn’t from the same background as my colleagues. The relationship with my boss wasn’t great, and I felt like she was only ever delegating work that was straightforward because she didn’t trust me. This made me feel less confident. It took a long time to feel comfortable saying, ‘actually, this isn’t working for me.’ Thoughout all my jobs, I’ve always put the monthly supervision in my boss’s diary. I always make sure we have that one hour per month. Other people don’t have that, or feel like they can’t ask for the time. We all need that opportunity to be able to check in with our supervisors. In terms of other management, my supervisor checks key documents I have drafted before I can send them out and we discuss how to progress cases.

Workspace

I work in an office in a medium sized building though we now have hybrid working, so sometimes I work from home. It can be tricky sharing an office particularly if they’re taking calls, but you learn a lot from hearing other people talk. Before the pandemic, you would generally share an office with someone that you were training or working with. However, after Covid-19, people often sit in offices by themselves. This is unfortunate, especially for the more junior solicitors, because you miss out on learning by osmosis. It’s really important for junior lawyers to share offices with more senior people because you can hear them advising on the law, how they take instructions, and how they reassure and handle anxious/upset clients. I appreciate being able to work from home though, because I hate commuting and it’s easier going to the gym/making lunch at home.

Pay

My work is paid for from legal aid funding and/or out of the settlement with a defendant. The costs we get from the case go to the overhead for running the firm. There are a lot of costs associated with it, and we’ve got loads of employees that need to be paid and a big office space. There can be expenses involved, like paying for travel, paper, photocopiers, and so on. A big issue is making sure that I’m able to bring in money quickly. In the firm I work in, we diversify our income and have teams doing different kinds of law to ensure we have a steady cashflow. In some departments, cases take a long time before they settle, so we need to ensure we also have teams bringing in cash more regularly. It always feels like there’s no money in the firm, despite making millions in profit in some years. I don’t know who gets that profit. I presume it’s the board and some of the partners. I’ve never had a bonus or anything like that at my firm.

Organising in the workplace

I do not think I have any leverage at my firm. Theoretically, I could have but I ultimately feel very vulnerable and feel like I could easily lose my job if I was openly part of a union. I’ve never been in a position where I’ve been able to organise with people to then create leverage. It’s difficult because if you’ve got a grievance and you try to raise it, it often just gets brushed under the carpet or you’re told that’s just the way things are. At the beginning of my time in my firm, I was being paid a lot less than my colleague without any good reasons. I tried to raise it and it didn’t really go anywhere. When I became a trainee, I remember telling people to check in with each other regularly about how much people get paid. They found out they were all being paid different amounts which they raised and managed to secure equal pay. I don’t think this is something that happens regularly, though.

There is scope for working together to ensure that we have better rights and are collectively in an equal position. This is something which is very difficult to do on your own. Getting people together is tricky, particularly because everyone is overworked and working long hours. This makes it difficult to do anything that isn’t just keeping on top of your case load. And some people just don’t want to organise in a union

We have had a lot of management issues at my firm. This can be costly, e.g. when people are placed on gardening leave. At the same time, every month, I’m under pressure to bring in fees and make sure I’m billing efficiently and settling cases. We care about our clients and their cases and we don’t make a lot of money for our clients. Obviously, we’re trying to settle the case for money and the best result for the client. However, we’re also having to deal with all this background pressure of these really senior people saying, ‘we need more money.’ This feels more for their interest and for the firm, because obviously we do need to bring in money.

Staff turnaround is a key issue for getting organised. We’re more likely to have junior staff involved in the union, because they feel the most vulnerable. If we had more senior staff involved in the union, it might be for the firm to punish anyone for their involvement. The turnover means we’ve got lots of people coming in and out, so it’s hard to create any kind of base. It’s also hard to get new people involved because we’ve not won anything meaningful so far. It means we’re arguing that theoretically a union would be a good idea without offering potential new members any concrete examples of achievements won through organising.

A lot of people aren’t from radical backgrounds. They aren’t from backgrounds where their parents were part of unions and can’t appreciate the power of unions. Perhaps they’ve heard people say it, but they haven’t experienced it. We also had a lot of drama. Particularly, when we were initially involved with a union where there was all this drama around finances. Now we’re with another union and, if I’m honest, neither of them have been that great. A lot of people asked, “well, what’s the point?” And I can kind of see where they are coming from. It’s difficult to keep up with the union on top of case loads. Some firms have been resistant to even negotiation with unions. I know people in our union who have sent letters to management and they didn’t even respond.

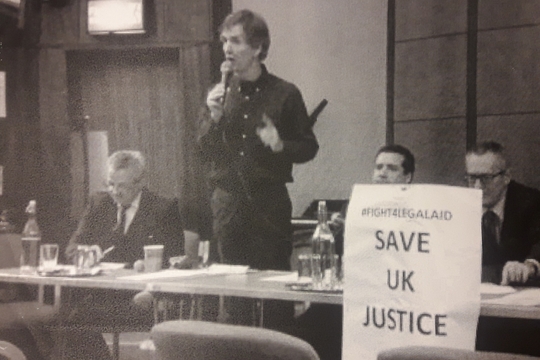

It’s a constant process of getting a few of us together and saying “fuck, we really need to start getting things going.” And then we start trying to get things going, but by the time it’s moving, we don’t have enough people. I think at some of the bigger firms they can get more people involved and start building. Each time we try again it gets easier, as we’re not starting from the beginning again and we’re trying something different. We’re going to get there. A lot of people get the importance of building a union and we want to work together. We want to ensure we have the same opportunities and rights. It’s going to take time, but if we don’t have a union, how can we know what’s going on across departments or different firms. We need that to organise around the important issues.

Featured in Legal Workers Inquiry (Book)

author

Louise Lorde

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Introduction to the Legal Workers’ Inquiry

by

Jamie Woodcock,

Tanzil Chowdhury

/

May 12, 2025