Równość - Kwestyjonaryjusz Robotniczy (1880)

theory

Równość - Kwestyjonaryjusz Robotniczy (1880)

by

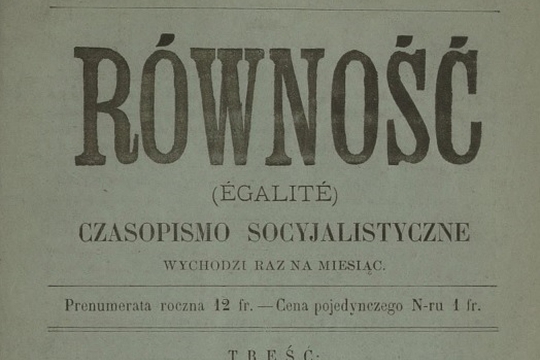

Równość

/

July 9, 2022

in

Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry

(#14)

Chapter Five

The following introduction to Marx’s inquiry, reproduced as Kwestyjonaryjusz Robotniczy in Polish, was included as a supplement to the July 1880 issue (no. 10 and 11) of the radical journal Równość, edited by Stanisław Mendelson in Geneva. It also included the original questions, slightly edited (these have not been reproduced here, present as they are in Marx’s inquiry reproduced in this volume). The introduction has been translated into English by Maciej Zurowski.

Workers’ Questionnaire

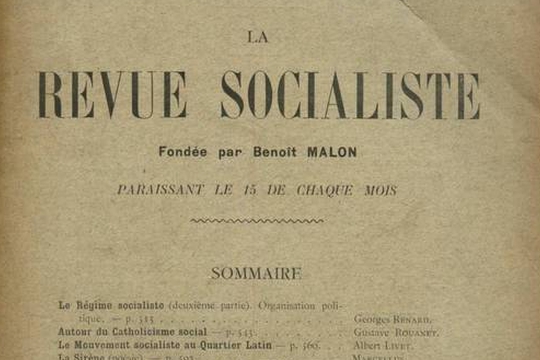

The set of questions printed below is a translation of a questionnaire published in the fourth issue of the French journal Revue Socialiste. These questions touch on almost all aspects of a worker’s life, and if one managed to compile many detailed answers, one would gain an accurate picture of the condition of French workers.

If such a questionnaire is considered necessary in France, it could be of great service to us as well. In France, the workers’ question has been discussed almost constantly for almost a century. It is a topic of conversation, it is written about, it is acted on: in books and in papers, you can often find a wide range of subjects of close concern to workers. In our country, in contrast, such things are not given any attention at all. ‘How does a worker live?’ – Apparently, that is not such an important matter that anyone would care about it. ‘How much does a worker earn daily?’ – What a strange question! ‘What does a worker each for lunch; what does he wear; in what kind of places does he live?’ – What ridiculous things to ask! ‘How does the foreman exploit the apprentice; how does the entrepreneur rob the worker?’ – To ask such questions is dangerous business. Indeed, it is tantamount to socialism, and the police isn’t joking around when it comes to socialism. Is one even allowed to write about such things in newspapers? – The papers are meant to print more important news: for example, whether a nobleman will or will not visit the country, whether this or that member of parliament will become a minister, whether a famous actress will leave our stages for good, whether last night’s concert was nice, whether tomorrow’s ‘charity’ ball will be a success – these are the really interesting topics that ‘everyone’ reads with pleasure.

Now then – let ‘everyone’ else keep reading about these important matters. Even if the questionnaire printed here is not of interest to ‘everyone’, it should nonetheless be of interest to workers. After all, their lives, and those of their families, depend on whether it’s easy or difficult to find work. Their health depends on whether working hours at the workshops are long or short. Their future depends on whether there is dough or not. Workers cannot be indifferent about these questions. They are more important to them than the fortunes of famous and not-so-famous actresses, eloquent and inarticulate members of parliament, benevolent and malevolent monarchs, and so on. So, if the papers do not talk about these matters, if they do not want to touch them, then workers have the right and duty to reflect and mull over these questions on their own accord.

This much is understood. But will anything tangible result from such contemplations – can replies to a questionnaire have any use for workers? Maybe – they could even be of great use. When today workers say again and again that they suffer hunger and poverty, they are talking about an ordinary problem. They have grown used to it, and they bear it patiently, occasionally complaining just to vent, to ease the pain. But how can they ease their pain when they do not know about each other, when they do not know what ails them, what makes them sick? After all, a doctor cannot cure a sick man if he does not thoroughly examine what hurts him and why. Likewise, as long as the workers are unaware how their comrades live, how much they earn and how they work – first and foremost those closest to them, then the workers from Prussia, Austria, Russia, and even France, Britain, and so on – they will not be able to help themselves. That is because each of them will have some different opinion on the causes of poverty and how to tackle it. One will say the Jews are to blame, another that it’s the Germans’ fault, a third one will say it’s because of drinking, a fourth one will blame godlessness taking hold among workers, a fifth one will argue it’s due to the practice of ‘mondaying’ (poniedzialkowanie),1 a sixth one will find entirely different reasons, and each and every one of them will have a different remedy for these ills. Only when all the workers learn about each other, become aware of their problems and begin to contemplate how to end them, everyone will identify the root cause of their eternal misery and hardship and join forces in order to abolish it.

This is also the reason why everyone who has any intention of improving the lot of the workers should begin to collect answers to these questions.

Since these questions are intended for France, they do not cover all aspects of our workers’ lives. In particular, there is a lack of questions concerning guild relations.2 In spite of this, however, one cannot help but wonder at the almost complete congruity between the things that ail the workers from the banks of the Seine and those from the Vistula, be they citizens of the Republic or slaves of the Tsar. It is obvious that the interests of the working people are always the same wherever there are entrepreneurs and workers, capitalists and proletarians.

Featured in Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (#14)

author

Równość

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Karl Marx - Enquête Ouvrière (1880)

by

Karl Marx

/

July 9, 2022