Postscript: Discovering Workers’ Power - No Politics Without Inquiry!

theory

Postscript: Discovering Workers’ Power - No Politics Without Inquiry!

by

Clark McAllister

/

July 9, 2022

in

Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry

(#14)

Chapter Sixteen

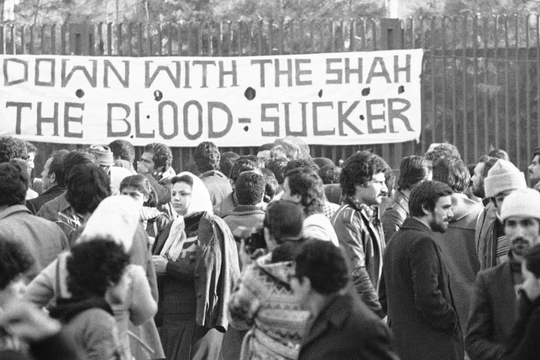

In almost all the struggles documented above, workers’ inquiry took place amidst hostile political environments, with numerous capitalist inquiries simultaneously undertaken into the labour-process to suppress worker organising. Some of these aimed to take control of the workplace (and the class-struggle) away from workers and place it in the hands of employers, while others tried to guide workers into moderate trade unions and bureaucratic organisations. Others still identified militant workers and removed them from society, often with brutal force, in order to prevent the working-class from realising and advancing its wider interests against exploitation.The most significant processes of capitalist inquiry, however, is explicitly referenced in the appeal launched by Przedświt in 1866:

Even though they rule the world today, capitalists never stop looking for ways to increase their power. Today they are investigating how to improve the tools of the trade, tomorrow they will be exploring ways to replace workers with machines; the next day they will be looking for new markets for their products – or rather, for the products they have appropriated – and so on.

As Przedświt emphasise, capitalists are constantly trying to escape from their reliance on the human commodity labour-power, because labour-power can only be the extension of living labour: embodied in the free-spirit of the worker, who might not consent to being bossed around all day and exploited. In order, then, to escape from workers constantly threatening the stability of the capitalist system, employers seek to “improve the tools of the trade”, “exploring ways to replace workers with machines”.

Unfortunately for them, labour-power is the most important commodity in circulation: the beating-heart of capitalism itself. It cannot be abolished without the abolition of capitalism, as labour-power is the only commodity capable of producing surplus-value, the source of both profit and capital. This is achieved through the particular capitalist organisation of work, where the cost of labour-power (and the fact labour-power has a cost), the wage, is cheaper than the value of the commodities workers themselves create in the process of production.

In order to balance this intolerable dependence of opposing classes, employers seek to refine the methods of exploitation in the labour-process, to monitor and control workers, so far as they need us, and limit our autonomy in the workplace. This renders the conditions of sale for ‘our’ commodity, labour-power, more beneficial for capital. It is necessary for employers, as the Przedświt workers’ inquiry emphasises, to therefore conduct their own inquiries, “to never stop searching for ways to increase their power”.

The most significant example of this is the phenomenon of Taylorism, dubbed by Harry Braverman as “the explicit verbalisation of the capitalist mode of production”.1 In the 1880s, Fredrick Taylor, an industrial engineer and factory foreman, inquired into workers’ behaviour on the shopfloor, taking careful note of strategies of resistance and reporting these to the bosses. Not only did Taylor’s efforts facilitate increased company control over workers, but he helped to devise strategies for physically limiting workers’ autonomy and power in the workplace. This rendered the physical organisation of labour-power more and more restrictive for workers, and ever-more valuable for employers. As Taylor argued, promoting the complete subordination of labour to capital, of the worker to their employer:

It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and of enforcing this cooperation rests with the management alone… All of those who, after proper teaching, either will not or cannot work in accordance with the new methods and at the higher speed must be discharged by the management.

This was perfected with the introduction of labour-saving machinery, giving rise to the modern assembly-line, where the speed of production could be centralised and controlled independent of the will of workers. This became the paradigmatic method of capitalist production into the twentieth century. While workers could not be replaced wholesale by machinery, they could at least be subordinated to it. Not only did such developments render a greater share of value for capitalist industrialists – who could reduce their labour costs considerably – but Taylor’s efforts, far from constituting neutral ‘scientific’ inquiries, represented a clear political attack on workers. Leading to a new generalised technical composition of the working-class (workers’ organisation in production), with little to no autonomy in the workplace, such a degradation was lauded by Taylor as the emergence of a “new man”, eternally at the service of the cult of work.

In spite of these efforts to control workers, the capitalist use of labour-power is a dangerous, explosive endeavour, no matter how it is organised. Embodied in our muscular energy and encompassing our stolen time, Marx called labour-power the peculiar commodity. It is peculiar, not only because it is the only commodity capable of producing value-as such (and, moreover, variable amounts of value, given varying organisations of work), but also because of the political character of the working-class. Even the assembly-line, and the massive changes this brought to the industrial workplace at the turn of the twentieth century, has been continuously used by workers to their own advantage. The new technical composition of the class actually granted workers increased disruptive capabilities. This was noted by Italian Marxists of the workerist tradition, who utilised workers’ inquiry during the 1960s: a period of intense social change in Italy, with a new migrant workforce engaging in ever-developing forms of mass-production. As Ed Emery has noted, it is generally at times like this, at “points of fracture, crisis, restructuring, dislocation of capitalist development etc that these Inquiries come about. And the Inquiries see themselves as a prelude, a precursor and a precondition of politics.”3

By inquiring into the activities of workers themselves, rather than proceeding from a priori assumptions over ‘correct’ forms of organisation, workers’ inquiry brought the Italian militants closer to the working-class. It opened up a space for Marxist strategy to proceed from class-struggle, rather than from outside – allowing socialist politics to proceed from the working-class perspective.

Inquiries of this sort are needed again, now more than ever. Today, having witnessed decades of neoliberal restructuring, the working-class remains largely fractured and disconnected. To many in the UK, the struggles of industrial workers in the 1970s and 1980s – from the Winter of Discontent to the Miners’ Strike – represented the last pitched battles between labour and capital. Today we are faced with a service-oriented economy with decreasing union membership and declining pay and conditions. Many on the socialist left have abandoned the class-struggle altogether, turning their attention exclusively to parliamentary issues, working within the bourgeois Labour Party, or to the myriad of activist causes and social movements. As important as these struggles are, they neither address nor aim to challenge the fundamental exploitative relation which structures capitalist totality: wage-labour.

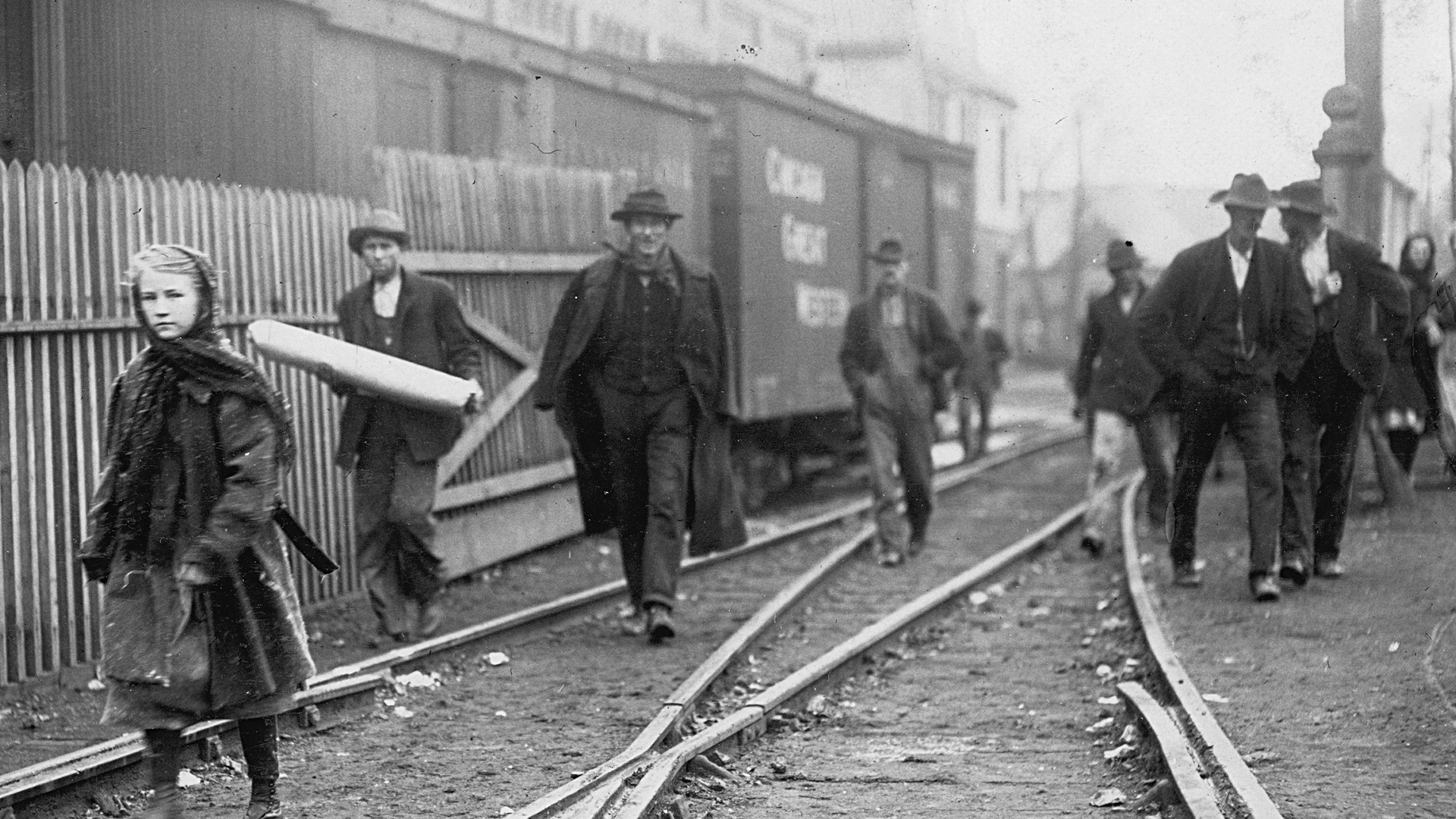

Our so-called service-economy might have blurred the lines of struggle considerably. But the fact is: there are more workers in Britain than ever. There are more factories – meat-packing plants, food-processing factories etc. – more offices, more construction work, logistics, and transport; more cleaning, more packing, more picking, more driving. There are millions of unorganised workers in supermarkets and warehouses - or, if there is organisation, it appears largely invisible to those outside the workplace. There are huge migrant workforces, often located on the fringes of cities, engaged in extremely low-paid and highly exploitative manual labour. The new composition of the class has not been sufficiently grasped by socialists, as sufficient attempts have not been made. As Emery said, inquiries are vital at periods of disjuncture and fragmentation: inquiry is a precondition of politics. Inquiry now, more than ever, is necessary: for the rebuilding not of abstract socialist influence, but of concrete working-class power.

Today, the militants of Notes from Below, as well as comrades across the world, engage in the practice of workers’ inquiry in order to advance this effort, continuing the project started by the workers movement and articulated in the works of Marx throughout the 19th century. Beginning from inquiries into the situation of the class-itself, which also allows us to understand the strength and composition of capital, the method of workers’ inquiry provides a compass for those who seek “to tear the direction and control of the class struggle from the brain of capital and put it once and for all in the fists of workers.” To this end, the reader is referred to the Class Composition Project – an ongoing collaborative workers’ inquiry through Notes from Below – with the optimism that we continue our efforts at building and re-composing a working-class power that dares to be reckoned with.

Further Reading

- Alquati, R., 1964, ‘Struggle at FIAT’, Classe Operaia, no. 1.

- Anastasi, A., 2020, The Weapon of Organisation, Mario Tronti’s Political Revolution in Marxism, New York: Common Notions.

- Angry Workers, 2020, Class Power on Zero-Hours, London: Angry Workers and PM Press.

- Chuang - chuangcn.org

- Dalla Costa, M., 2019, Women and the Subversion of the Community, A Mariarosa Dalla Costa reader, Oakland: PM Press.

- Denby, C., 1978, Indignant Heart: A Black Worker’s Journal, Boston: South End Press.

- Emery, E., 1995, ‘No Politics Without Inquiry!’, Common Sense, No. 18.

- Haider, A. and Mohandesi, S., 2013, ‘Workers’ Inquiry: A Genealogy’, Viewpoint Magazine, Issue 3.

- Hoffman, M., 2019, Militant Acts: The Role of Investigations in Radical Political Struggles, Albany: State University of New York Press.

- James, S., 1953 [1972], “A Woman’s Place” in The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, London: Falling Wall Press.

- Monaco, L., 2019, ‘Between Research and Organising: Some Reflections From Workers’ Inquiries in UK, India and South Africa’, Notes From Below, November 2019.

- Notes From Below, 2020, From the Workplace: A Collection of Worker Writing

- Ovetz, R., 2020, Workers’ Inquiry and Global Class Struggle: Strategies, Tactics, Objectives, London: Pluto Press.

- Pagliacci Rossi - pagliaccirossi.org.

- Red Notes, 1978, The Little Red Blue Book: Fighting the Layoffs at Fords

- Roggero, G. and Lassere, D. G., 2020, ‘“A Science of Destruction”: An Interview with Gigi Roggero on the Actuality of Operaismo’, Viewpoint Magazine, April 2020.

- Romano, P. and Stone, R., 1947, The American Worker

- Tronti, M. 1966 [2019], Workers and Capital, London: Verso

- Workers’ Inquiry Network, 2020, 'Struggle in a Pandemic: A Collection of Contributions on the Covid-19 Crisis’, Notes From Below, Issue 11.

-

Braverman, H., 1974, Labor and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century, New York: Monthly Review Press: 60. ↩

-

Taylor, F. W., 1919, The Principles of Scientific Management, New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers: 83. ↩

-

Emery, E., 1995, ‘No Politics Without Inquiry! A Proposal for a Class Composition Inquiry Project, 1996-7’, Common Sense No. 18: 5. ↩

Featured in Karl Marx's Workers Inquiry (#14)

author

Clark McAllister

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next