Organising the suburbs

inquiry

Organising the suburbs

by

Fiadh Tubridy

/

Feb. 21, 2023

Spatial composition, history and place identity in South Dublin

This article reflects on a project which I coordinated as a member and organiser of the Community Action Tenants Union Ireland (CATU) involving research on previous forms of housing activism in my local area in Dublin and a walking tour on this topic in August 2022. This was not initially conceived as an exercise in workers’ or territorial inquiry1 but has led to reflections on place identity and spatial composition, with spatial composition referring to how political organisation is interrelated with the configuration of space, including the geographical distribution of the working class, and struggles to transform it.

The background to this piece is that of the ongoing ‘housing crisis’ in Ireland (although the crisis narrative undeniably overstates the novelty of the present moment). Indeed, the present situation has deep roots in the Irish state’s housing policy and broader economic model, including a century-long strategy of selling off local authority housing, and general reliance on land and property speculation and rentier capitalism as core methods of accumulation.2 This is apparent in the credit-fuelled property bubble and consequent banking crisis that intensified the impact of Great Recession for the Irish economy and, more recently, in the state’s facilitation of international investment in the private rental sector, leading to the proliferation of Built-to-Rent developments and so-called ‘vulture funds’. CATU, in turn, is the most recent way in which tenants and others facing housing problems have sought to organise ourselves since the Great Recession, in response to changing conditions and as organisational strategies have developed.3

CATU is a membership-based tenant and community union that uses direct action to directly confront landlords, local authorities and other targets.4 Its membership base is primarily composed of younger tenants in the private rented sector in major urban centres including Dublin, Belfast and Cork. Despite this, CATU has always understood and positioned itself within a broader tradition of community organising in Ireland outside the sphere of housing, including recent mass movements against water charges and for abortion and LGBT+ rights.5

The specific project discussed in this article was undertaken by my local CATU branch in Dún Laoghaire, a coastal suburb to the south of Dublin city centre, an area with a reputation as affluent and middle class but whose actual class composition will be discussed in this piece. The project comprised research on previous housing campaigns in the area based on archival research and a small number of interviews with former community organisers where available, which provided the basis for a walking tour and collective discussion about the area and its history. The project was conceived in response to the precarity and hypermobility forced upon renters by the housing situation and aimed to provide local CATU members with a better understanding of the area and community in which we have come to live and provide us with a sense of ownership and rootedness that might reinforce our determination not to be pushed out. The walking tour took place in August 2022 and was intended both as a form of popular education as well as a way to bring local CATU members and other members of the community together around a shared interest in housing and community activism.

The following sections provide an account of the walking tour and previous instances of housing activism which were discussed with a broad focus on spatial class composition or, more clearly stated, the fact that housing activism in the area has typically taken place in a context where landlords and tenants live cheek by jowl. The implications of this situation and the value of the project are discussed in the final section of the piece.

The Walking Tour

The first stop on the walking tour was at Crosthwaite Terrace, three large and impressive houses built around the 1820s for members of the Anglo-Irish colonial elite. By the early 20th century, and similar to other stately houses across Dublin, they had been subdivided into barely habitable tenements let by rack-renting landlords and, in the 1930s, and were the site of a short-lived but dramatic rent strike organised by activists from Republican Congress. On the walking tour, we observed that two of the houses are visibly poorly maintained which is related to the fact that they remain subdivided into small, rented apartments.

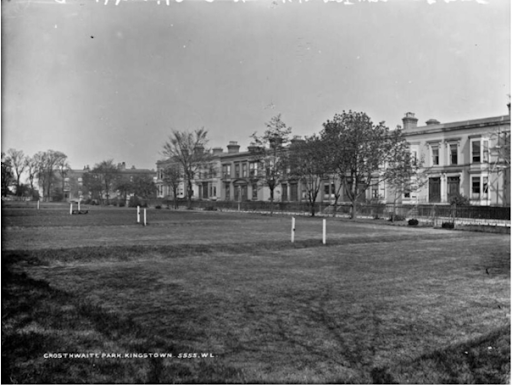

Crosthwaite Park, Dún Laoghaire, pictured at some point in the late 19th or early 20th century.

The general background for the Crosthwaite Terrace rent strike was the Great Depression and mass unemployment in the crowded slums of Dublin, Cork, Waterford and elsewhere. There was also a growing threat posed by fascism in Ireland with the increasing influence of the Blueshirts6 who had planned to carry out a march on Dublin in 1933. In response, Republican Congress had been formed out of a split in the IRA in 1934 due to the dissatisfaction of left-wing Republicans with the movement’s lack of direction and involvement in social struggles. It was formed with the objective of providing a “a united front that would rally all shades of anti-fascist and republican opinion”.7 They were active in strikes and anti-fascist activity including resisting a Blueshirt rally in Dun Laoghaire in summer 1934.8 A key aspect of Congress activity was tenant organising, particularly in tenements and slum housing. Congress activists were involved in the establishment of ‘tenants leagues’ across Dublin and their activities included resisting evictions and organising rent strikes, most famously the successful York Street rent strike in Dublin city centre.9

Numbers 1 and 2 Crosthwaite Terrace were also the site of a rent strike and evictions which were resisted by Republican Congress and the Dún Laoghaire Tenants League in September 1934. At the time both houses were subdivided into one room tenements where tenants were paying up to 90% of their income to live in atrocious conditions. According to a newspaper report, “open sewerage, rats and vermin contribute to the dangers under which the tenants live”.10 In response several of the tenants had started a ‘no rent’ campaign, or in other words begun a rent strike. Soon after two of their number were evicted by the landlord but later the same day a crowd of 100 people overpowered a policeman and put the furniture back in the houses. At a mass meeting to protest the evictions the people of Dún Laoghaire were congratulated on the “rising militant spirit evidenced by the no rent campaign against insanitary houses”.11 The conclusion to the events at Crosthwaite Terrace was mixed, with several tenants appearing in court and limited information about the end of the campaign.

The Second Stop

The situation encountered by the Dún Laoghaire Housing Action Group (DLHAG), whose activities were discussed at the second stop of the walking tour, were in many ways similar to those pertaining in the 1930s. This was a housing action group composed primarily of activists from Official Sinn Féin which was active in the late 1960s and early 1970s and used direct action and squatting to resist evictions and oppose property speculation. On the walking tour we stopped on the site of the former Adelphi Cinema where DLHAG waged a long campaign to prevent several residential houses being demolished and converted into a shopping centre by supporting homeless families to take up occupation. The shopping centre was never built but the houses were eventually demolished in the late 1970s and the site is now occupied by the ‘Adelphi Plaza’ development consisting of a mixture of high-value offices and apartments. A general history of the DLHAG has been written up elsewhere so does not need to be recapitulated12. However, one important point is that, while some council housing had been built since the 1930s in surrounding areas including Sallynoggin and Monkstown, the majority of their organising and actions remained focused on the privately-rented slum housing and tenements in the streets and Victorian squares adjoining Dún Laoghaire town centre, where landlords and tenants continued to live in close proximity. One example of this was an eviction at Belgrave Square West in Monkstown which was resisted by the DLHAG. After helping the family to move back into their home activists crossed the street to picket the owners’ home at Belgrave Square East.13

A notable feature of both the Republican Congress and DLHAG campaigns is the similarity with the present in terms of spatial context and composition; today Crosthwaite Terrace is set amongst well maintained owner-occupied homes that change hands for upwards of €1-2 million, but Numbers 1 and 2 are still subdivided into small, poorly maintained apartments with an average monthly rent of over €1200. The situation in other nearby streets and squares is similar and reflects a distinctive social geography involving the close proximity of modern tenements to other households in a starkly different class position. Thus, similar to the 1930s and 1960s, tenants today are fragmented through having individual relations with a patchwork of private landlords. However, there are arguably important differences in terms of political composition in the sense that in both the 1930s and 1960s there were active and militant working class political movements which allowed tenants to overcome their spatial fragmentation and act collectively. This is evidently what we, as the local CATU branch, are trying to achieve today through our local branch structure. I will come back to the challenges and successes of our ongoing efforts towards the end of the article.

The Third Stop

For the third stop of the walking tour, we left Dun Laoghaire town centre proper for the nearby suburb of Sandycove. We stopped at Eden Park, a leafy Victorian Terrace, where one recently advertised house was described in the property pages as “a prime piece of real estate in one of Dublin’s most upmarket suburbs”,14 obviously an unlikely seeming place to talk about housing activism. Here we discussed a campaign against the charging of ground rents which took place in the early 1970s at the same time the DLHAG were active. This represents another campaign and form of organisation which emerged from the distinctive spatial composition and corresponding class alliances in the area. The ground rent system itself was a distinctive colonial holdover which was a result of the fact that much urban development in Ireland had taken place on land that was leased rather than bought from estates owned by landed gentry of the Anglo-Irish upper class. This was equally the case around Dún Laoghaire where new suburban private housing was built on land leased from the Proby Estate in middle-class areas to the East including Sandycove, Dalkey and Killiney. In the 1970s the ground rent system raised an estimated £10 million per year for landlords in Ireland and it was common for eviction orders to be sought for non-payment.15

Beginning in the late 1960s the Proby Estate sought to massively increase ground rents and evict homeowners if the increases were not paid. In response, ground rent tenants in the area formed the Sandycove Ground Rent Tenants Association which tried to pressure the estate to drop the evictions and the government to abolish the ground rent system. Notable actions during this campaign included a picket of Eton College where the ground rent landlord, Peter Proby, was the bursar, and the firebombing of the house of the landlord’s brother and agent (which the Sandycove tenants denied any involvement in). Their campaign was strongly supported and promoted by Official Sinn Féin because it fit with the party’s strategy to oppose ‘economic imperialism’ and build a base that would cross class lines by including socialists as well as traditional Republicans.16

Overall, the Proby Estate campaign was highly successful. It lead to the introduction of new legislation which made it easier to buy out ground rent leases and also built momentum for a national campaign for the abolition of the ground rent system. In 1973, the Association of Combined Residents Associations (ACRA) started a national ground rent strike which continued in effect for over 20 years, led to the withholding of £70 million in ground rents and forced further government action. However, while this is undeniably an important success, aspects of this campaign which focused on the defence of private property rights should give pause for reflection. As described by an ACRA spokesperson “what we seek is no more and no less than the right of the householder to full ownership of the piece of land on which his [^sic] house stands and thereby the house”.17 This is evidently connected to the specific class alliance and context and the fact that this issue was so effectively able to mobilise middle-class homeowners in what were and still are some of Dublin’s most affluent areas. It is generally an ambiguous legacy for us as current community and tenant organisers to reckon with, including as we consider to what extent we should try to identify shared grievances and form alliances with other local community groups.

The Fourth Stop

Walking tour discussion on the grounds of the former Proby Estate in Sandycove.

The fourth and final stop of the walking tour involved a discussion of a successful campaign to improve conditions in council housing around Dún Laoghaire in the late 1980s. This took place at Glasthule Buildings, one of the few remaining cohesive pockets of council housing in the area. Glasthule Buildings is now comparatively well-maintained, especially compared with other social housing estates in Dublin, which is likely linked to its location in Sandycove as well as Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council’s position as the wealthiest local authority in the country. Again, the outlines of these events have been written up elsewhere so do not need to be retraced, but the key point is about how this campaign arose in a very different spatial and social context of discrete, identifiable concentrations of council housing which was reflected in the organising strategies adopted. As described by one of the main organisers in an interview with the author, “we knocked on every council house door, every estate we could find, so it was very comprehensive. In central Dún Laoghaire in particular, you had a coherent, long-standing community in a very compact area of social housing. In our campaign, we really were organising a community. Once you got a critical mass, once you got one person or one family in each street, it just rolled out by itself almost, because it was an organic community that existed already.”

This provides grounds for reflection on council housing and spatial composition generally. Another ongoing CATU project concerns the wave of rent strikes that took place in Ireland in the early 1970s. This also emerged from a distinctive situation in terms of spatial composition where large numbers of tenants of the same landlord lived in close proximity in a way that presented obvious opportunities for organising. Starting in 1973, and partly as a result of the rent strikers’ demands, there were mass sell-offs of council housing that fundamentally undermined the structure of the tenants’ movement.18 Following this, the infamous ‘Surrender Grant’ introduced in 1984 provided financial incentives to council tenants to give up their rented homes and buy privately elsewhere. This led to a mass exodus from council estates, primarily of tenants in stable employment who could afford to take advantage of the terms of the grant and who were often also important community activists.19 All of these processes equally impacted on housing and spatial composition in Dún Laoghaire and mean that organisers today are faced with very different conditions to those pertaining in the 1980s.

Walking tour participants at Glasthule Buildings.

Spatial Composition

In the article so far, I have tried to explore spatial composition in one specific Irish urban centre as traced through a history of local housing action. The general situation is not by any means unique to my local area and the analysis is not entirely new either. Others have highlighted a similar situation in the UK where major rent strikes such as in Glasgow in 1915 or those involving council tenants in the late 1960s and early 1970s emerged in very different contexts in terms of political and spatial composition. Likewise, there is a similar situation now where private tenants in the UK are generally ‘atomised and fragmented’ except in distinct circumstances such as student housing.20 In Ireland CATU is trying to build relationships and organisation through its local branch structure in the face of a general fragmentation of working class communities. Further interrelated challenges include the precarity and hypermobility of private tenants who are frequently forced to uproot and move elsewhere in ways which disrupt place-based relationships built through dedicated organising work.

Returning to Dún Laoghaire, one important issue is the continuity in terms of fragmentation and decomposition, associated with the intermingling and spatial proximity of landlords and tenants and the fact that tenants appear (or do not appear) as an invisible underclass spread out amidst a suburban landscape dominated by middle and upper-class homeowners. This situation leads to some basic organising challenges including identifying and building connections with other working class people and tenants. Through our experience, we have found that the classic organising strategy of trying to comprehensively knock on doors throughout the area is not effective due to the resources and time required, and how disheartening it can be to meet with a positive response so infrequently. Instead, it has proven much more effective to focus on visible forms of action that can attract public and media attention. This has drawbacks in terms of reaching people who are not already in left-wing circles or social networks but so far has worked sufficiently well to build an active and militant branch of the union.

Beyond this, there is a further set of organising challenges related to the subjective dimensions of place and class, or in basic terms the lack of oppositional working class culture and identity. At least in my experience, there is a tendency for people to refuse to see themselves as working class arising from the fact that they feel they should be grateful for their position or that ‘other people have it much worse’ which can be linked to and intensified by the area in which one lives. These feelings may be grounded in recognition of real differences between sections of the working class but can also act to undermine the recognition of shared interests which is key to class consciousness. In an Irish context, this is likely to be further intensified by a confused understanding of class where this is taken to directly emerge from the area in which one grew up or lives.21

Place, including in its subjective or imaginative dimensions, is one important way in which class becomes real and comes to have substance and meaning in people’s consciousness and lives. Building a specific, oppositional place-based identity is therefore one way in which class consciousness can be developed. This returns us to the function of the CATU walking tour and radical history project which aimed to begin this project of both analysing the position we are in and building a militant, counter-hegemonic local identity grounded in an understanding of past struggles. At least from my perspective the project was successful in contributing to this. In terms of the immediate outcomes, it coincided with an increase in local activity with new members joining the union and a broadening of the local committee. Although more difficult to quantify, my own sense and the feedback from other participants suggests that it has also contributed to cohering a sense of vision and identity linked to identification with past struggles, which can immediately be recognised as important sites of working class political action, and a corresponding re-inscription of our area and what it means to live here as offering possibilities for similar forms of activity today.

-

Gray, N. (2019) Notes Towards a Practice of Territorial Inquiry ↩

-

McCabe, C. (2013). Sins of the Father: Tracing the decisions that shaped the Irish economy. ↩

-

Hearne, R., O’Callaghan, C., Di Feliciantonio, F. & Kitchin, R. (2018) “The relational articulation of housing crisis and activism in post-crash Dublin, Ireland”, in N. Gray (Ed.) Rent and its Discontents: A century of housing struggle. London: Rowman and Littlefield. (This does not deal with CATU directly but provides an account of different housing movements that have emerged in response to changing conditions since the Great Recession). ↩

-

https://catuireland.org/is-there-power-in-a-union-part-1/ ↩

-

The Blueshirts were the armed wing of Cumann na nGaedheal, since renamed Fine Gael, which is one of the two right wing parties which has dominated politics in Ireland since Independence and is currently in government. In the 1930s many leading Blueshirts travelled to Spain to fight for the fascists in the Spanish Civil War. ↩

-

Byrne, P. (1994). The Irish Republican Congress Revisited. ↩

-

Republican Congress, 16th June 1934 ↩

-

https://comeheretome.com/2018/10/09/the-tenants-leagues-of-1930s-dublin/ ↩

-

Republican Congress, 15th October 1934 ↩

-

Republican Congress, 29th October 1934 ↩

-

https://catuireland.org/there-were-some-molotov-cocktails-thrown/ ↩

-

Sunday Independent, 10th August 1969 ↩

-

https://www.independent.ie/life/home-garden/couple-relocating-to-the-us-are-selling-their-elegant-home-in-one-of-dublins-most-upmarket-suburbs-37799346.html ↩

-

Ground Rent is Robbery, Official Sinn Féin pamphlet, 1974 ↩

-

United Irishman, 7th August 1968 ↩

-

Evening Herald, 16th January 1976 ↩

-

Zagato, A (2012). Community Development in Dublin: Political subjectivity and state cooption. PhD thesis. ↩

-

Downey, A. (2020). The Counter-Production of Space: Geographical Organising, Housing and Class Composition in Dublin - Regeneration and the Case of St. Michael’s Estate. MSc Dissertation. ↩

-

Rose, I. and Donnachie, S. (2020) ‘Defending our homes against landlord tyranny’: Rent strikes, then and now. ↩

-

https://anarchism.pageabode.com/blog/seomra-prompted-thoughts-on-class-definition-community-and-exclusion/ ↩

author

Fiadh Tubridy

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?