NHS pay dispute from below no.2

bulletins

NHS pay dispute from below no.2

by

Health Workers United

/

Aug. 17, 2021

Online newsletter

Republished from Health Workers United.

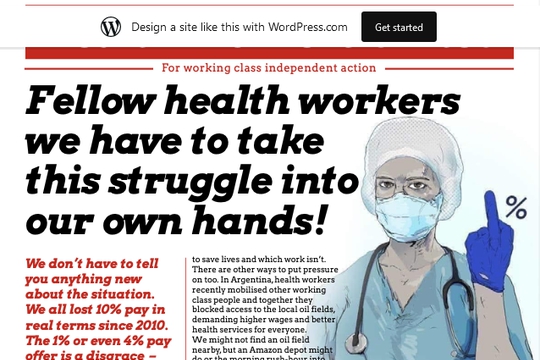

Welcome to the second newsletter for a workers-led NHS pay dispute! The various trade unions are slowly starting to inform their members about the consultation – if you are a member, please vote to reject the 3% government pay ‘increase’ decision. Inflation is expected to rise to up to 4% – we might be in for another real wage cut. Here are a few things that we should bear in mind over the coming weeks – until the union consultation closes.

-

As health workers we are between a rock and a hard place. The government won’t budge and improve the 3% pay ‘increase’. It will need a lot of pressure to get a better wage. The unions will have to do something to build this pressure, but they are not used to it. They are used to petitioning, symbolic protests, perhaps a demonstration. They are afraid of taking industrial action on a larger scale, last but not least because it might cost them money. At the same time, they have promised members a lot, so they have to show that they are doing something.

-

The most likely outcome of this pay dispute is that the unions don’t manage to get enough people to vote in favour of industrial action. This might actually be the best outcome for the union headquarters, as they could say: “We wanted to mobilise our members, but they decided not to pursue the struggle”. They would not have to do much, but would not lose face. According to the law, there has to be one official industrial ballot to take action – as if that wasn’t enough of a hurdle, the unions add two more ballots: the current ‘consultation’ and then an ‘indicative ballot’. It is hard to encourage people to vote three times whether or not to do something!

-

The question is also whether the pay question is enough of a motivating issue. Any percentage increase will widen the already stark wage gaps between the different bands. For example, with the current 3% increase that the government wants to give us, a worker on Band 2 will get only about £580 more per year, while a Band 6 will get £1,130 and a Band 9 over £3,000 extra. We have to bring other issues to the table – first of all staffing levels and work stress. Both government and union headquarters will say that this is not possible because this is a ‘pay dispute’ – but if many of us agree that not only pay, but also work stress is a major issue, they can’t stop us.

-

We will see a few information stalls and activities by the unions in the coming weeks. Up to now they are timid, on the fringes of the hospitals, e.g. handing out free coffee in the car park. If we want to get more of our fellow colleagues involved we have to bring this dispute into the centre. Let’s call for general meetings of all groups of workers during break-times. Let’s take leaflets and inform others by visiting other wards or surgeries. Let’s not stand at the side entrance, but in the centre of the hospital!

We need to share our experiences, please send us your ideas and observations: [email protected]

— Reports —

* Short report from a Unison pay campaign activist meeting, South West England

I am a health worker employed at a hospital in Bristol and I took part in an online meeting organised by Unison. Although the meeting was announced as an ‘activist’ meeting, it was mainly a panel of paid organisers who talked. They informed us about Unison’s general position on the pay dispute. They claimed that it was ‘campaigning’ that moved the government to increase the offer from 1% to 3%. This is questionable, but this version of events pleases both sides: the government can say that they ‘improved’, and the union headquarters can say that they’ve already ‘achieved’ something.

There was no real contribution from different union branches, no exchange of ideas about what to do. It was mainly the paid officials telling people what kind of material, arguments and conversation strategies there are in order to convince members to vote. One of the main questions was not discussed: what kind of industrial actions are there apart from an all-out strike? For many colleagues it seems that the only option is to either accept the offer or to go on strike. But a strike is quite a hurdle – there are concerns about the patients, about losing pay. We have to discuss other forms of industrial action which seem easier to take, as a first step. Work-to-rule, for example, where you only perform tasks that are in your job description. Or a collective refusal to work bank shifts. We might need a full-on strike, where only the most essential tasks are performed in order not to risk patients’ lives – but we have to build up to that by trusting each others and our creative abilities.

* Brief workplace report from a mental health worker, north of England

I work in a community mental health team in the north of England. This is a brief report of our experiences over the pandemic and some initial thoughts about how it relates to the pay deal. Like everyone in health and social care, we’ve had a pretty tough 18 months. The pandemic came on the back of a recent change in our team structures, and we were already struggling with staff shortages and constant rounds of not-that-successful recruitment. Like everyone, we had to adapt quickly to the lockdown, moving to remote working, and we were suddenly faced with even more pressure on staff due to team members being redeployed onto the wards and staff shielding. We had the weird experience of GP referrals going down in the full lockdown, but with more people coming to us in crisis, and we all had to change how we worked and found ourselves being even more reactive and fire-fighting than usual.

As things have opened up we’ve started to do more face-to-face working, and starting to see each other and our patients in real life has made work feel slightly pleasant and less surreal. But the staff shortages have actually got worse. I don’t know how many ‘sorry to see you go’ cards I’ve signed in the last few months and we’ve struggled to recruit even into quite senior posts. Care co-ordinators have got caseloads of really unwell patients of 40+ and it’s hard to feel like you’re doing your job properly. We’ve had a load more people off with Covid recently even though vaccinated and others off for mental health reasons, and it’s hard not to feel cross about ‘freedom day’ when we’re still feeling the impact quite severely, even if things haven’t gone as badly as we feared they might.

There’s been no talk at all in my team about the pay increases, and it feels a bit hard to raise as one of the more senior members of the team. I’m sure there’s a few reasons for this: the lack of communication from our unions, the fact we’re split between different professional groups and unions, and the focus of our concerns and stress being about workload and staffing rather than pay and just being completely and utterly exhausted. There’s also the fact that we’re still mostly working remotely, and even aside from that, as a community-based team, we don’t spend that much time together and don’t really have a staff room. I also think we can easily buy in to the ‘hero’ or ‘angel’ culture that’s been encouraged in the pandemic. As well, the fact that our team’s strong identity and sometimes quite an ‘in-group’ mentality means that we have a culture of ‘just getting on with things’, or blaming problems on other teams and colleagues, rather than thinking more widely about politics, services structures and organisation. I’d be pleased to hear from others about the steps that can be taken to overcome this and shift the culture from pay being a bit of a taboo, to being something that’s important to talk and join in struggle about.

* Brief report on resources, capacity and commissioning problems for community mental health workers, South East England, Summer 2021

It feels like workers are having to accept being under-resourced as an ordinary part of the job. The team I’m with has lost a third of its staff in three years, through cuts and workers transferring out or moving on. Community mental health services in England are funded by the NHS and local authorities/councils. A freeze on recruitment just now means council employed workers who’ve left during the last year aren’t being replaced. There’s a promise of some health funding coming to match the gaps, but these things take time. When workers leave it can be months before their posts are covered, even temporarily. In the meantime, work needs picking up. At present, workers can be responsible for up to thirty peoples’ care at one time. On service they should average about half this amount to allow for the kind of flexibility needed for purposeful, responsive mental health outreach. It’s a service set up to work with patients whose needs tend to go unmet in more generic teams, but with less capacity the kinds of care/treatments on offer end up being reduced or restricted, becoming less meaningful. It’s upsetting. Expectations from commissioners and other providers haven’t really shifted with the reduced capacity, so workers are being stretched to meet service agreements they can’t honour with the resources they have.

Commissioning groups monitor the services planned and purchased with NHS funds to check they’re on track and doing what they’re supposed to. This isn’t novel to the pandemic but with more remote/online working this last year, it feels like there’s also been more day-to-day monitoring of how the work gets done. It’s become commonplace to have commissioners copied into emails and involved in more routine aspects of the work, including decisions about direct patient care. This feels like a new development from previous contract-review processes in that there’s now a kind of real time performance monitoring for partner/customer satisfaction. Other services and care providers are encouraged to report and appeal to commissioners’ powers to intervene if they’re dissatisfied with how the team is working. Whilst this probably helps with things like accountability, and maybe even draws attention to the resource gaps, it more often undermines trust and dials up antagonisms between different groups of workers. It takes effort and care to recognise these problems and attend to them in ways that keep us working together.

* Successful campaign by paramedic students in Scotland

We don’t know much about this campaign, but it seems relevant when discussing what collective action can achieve. From the press release: “Today represents a monumental win for student paramedics across Scotland, with our campaign achieveing its goal of winning a bursary equal to that of nurses and midwives. The difference this will make to the lives of hundreds is gigantic. The pressures of food poverty, worrying about rent and mental health will all be eased. This bursary was won because student paramedics came together to fight against an obvious injustice. Our reports over the past year have shown the financial and mental strain completing this course without a bursary takes.”

https://www.paystudentparamedics.org/

* A book to read: “The Next Shift – The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America”, by Gabriel Winant

https://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674238092

This book on changes in the working class in the USA seems interesting and insightful. Pittsburgh was once synonymous with steel. But today most of its mills are gone. Like so many places across the United States, a city that was a centre of blue-collar manufacturing is now dominated by the service economy—particularly healthcare, which employs more Americans than any other industry. Gabriel Winant takes us inside the Rust Belt to show how America’s cities have weathered new economic realities. In Pittsburgh’s neighbourhoods, he finds that a new working class has emerged in the wake of deindustrialization.

As steelworkers and their families grew older, they required more healthcare. Even as the industrial economy contracted sharply, the care economy thrived. Hospitals and nursing homes went on hiring sprees. But many care jobs bear little resemblance to the manufacturing work the city lost. Unlike their blue-collar predecessors, home health aides and hospital staff work unpredictable hours for low pay. And the new working class disproportionately comprises women and people of colour.

Today healthcare workers are on the front lines of our most pressing crises, yet we have been slow to appreciate that they are the face of our twenty-first-century workforce. The Next Shift offers unique insights into how we got here and what could happen next. If health care employees, along with other essential workers, can translate the increasing recognition of their economic value into political power, they may become a major force in the twenty-first century.

* International news

Last week there we saw many struggles of health workers all over the globe. Nurses in the Philippines threatened strike action after not having been paid their Covid bonus, while the health minister is embroiled in corruption charges (sounds familiar?!). Nurses are still on strike after several months at St.Vincent hospital in Massachusetts, USA. In France, health workers gear up for a national strike against compulsory vaccination decreed by the government. In New Zealand midwives are on strike and they are on strike for real: they cancelled elective c-sections! In Berlin, Germany, health workers at two major hospitals are getting organised for strike next week, supporters set up a ‘solidarity camp’ with entertainment, workshops and other activities. In Northern Ireland mental health nurses went on a ‘safety strike’, after an increase of attacks and lack of staff. There were also strikes of nurses in, amongst others, Peru, Kenya and India. To follow these news, check out our Twitter feed:

@healthworkersu1

author

Health Workers United (@@healthworkersu)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

NHS pay dispute from below no.1

by

Health Workers United

/

Aug. 9, 2021