Making a Scene In Arts and Culture

by

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

August 22, 2025

Featured in Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture (#24)

Our editorial for issue 24, Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture.

theory

Making a Scene In Arts and Culture

by

Notes from Below

/

Aug. 22, 2025

in

Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture

(#24)

Our editorial for issue 24, Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture.

This issue is dedicated to Marina Vishmidt.

Introduction

Nothing concerning artist and cultural worker organising can today be considered self-evident. The horizons of workers’ struggle within the ‘creative economy’ have in many ways been recast by a combination of long-term, generalised crises of work in the sector - only exacerbated by the pandemic - and mass activity around institutional complicity in the on-going genocide in Palestine. We see a continual proliferation of critical perspectives on the neoliberal artworld, and ever-more justified laments about the shape of cultural activity amidst the decay. But, if we are resolute in our opposition to the evacuation of culture, through the collapse of funding or in the explosion of AI production, then it is toward worker self-activity that we must above all be attuned. In this issue, we offer a snapshot into the struggles unfolding across the breadth of the sector, collecting writing and reflections from those organising in the crisis-ridden galleries, museums, theatres, and offices that underpin cultural production today.

Earning a living in the Cultural Industry

The specific character of ‘artistic’ and ‘cultural’ labour has long been debated, but in this editorial we do not wish to relitigate on this issue at any great length.1 That artists, game workers, stage actors, and gallery assistants share only limited similarities in the labour processes of their ‘creative’ work will be obvious when reading through the following pieces. Rather, our focus is on engaging workers in situ. It is only by beginning with workers in their everyday experiences of work, and struggles to organise, that we can make sense of how these disparate sectors are tied together, and what forms of worker unity across the ‘cultural industry’ are being forged. We ultimately follow Marina Vishmidt in her reflection that within this space, “serious labor organizing within capitalist relations of production and power cannot start from the anomaly, but from commonality.”2 The questions we pose, and which this collection of reflections try to answer, are: how do the diverse range of technical compositions of cultural work lend themselves to building leverage? How are the conditions in which cultural workers are situated producing new political forms? What types of relationships are possible within and against the state’s arts policies and the market regimes of the sector? Simply put, what power can these workers exercise?

The workers writing in this issue are reliant on a range of different sources of income to survive. Some are in waged work within large institutions, funded both privately and publicly, intermittently subsidised and propped up by the state, while others share these same workplaces but are on outsourced contracts to large private firms. Others are reliant on commissioned or freelance labour, living through short-term contracts, or are constantly scrabbling for grants. A number work in hugely, directly profitable sectors like in the video games industry, and others are in the deficit-prone, financially mismanaged networks of galleries and museums that are unevenly distributed across the country. We also see the vast streams of unpaid and unrecognised work that keep things afloat, and which many cultural workers are compelled to take on under the forever deferred promise of future success. The social composition of these workers varies greatly, with many tied into the global circuits of migration and precarity that underpin the overlapping service economy. There are the clear stratifications along lines of race and gender that reproduce the economy at large, alongside arcane status hierarchies that are unique to the arts world in other ways. Workers are largely organised - if at all - into competing unions which are partly defined either by their quasi-’craft union’ character or through their professional status, the largest of which rarely depart from the social partnership relationships which keep employers comfortable. Platforms like IWGB’s Game Workers Union or Artists Union England have emerged more recently, displaying a greater commitment to democratic forms, although they remain relatively smaller platforms still developing their scope of organising. Here, we should note that there are obviously crucial workforces not represented in this volume - be that musicians and technicians, or community arts facilitators and graphic designers - so, as ever, we warmly invite reflections and responses which develop our collective attempts to understand the sector in its current state.

This heterogeneity of the workforce, and the particular compositional histories of each sub-sector, generates difficulty in building a shared sense of power. But informal networks and organisations have emerged to combat the deep deficit of either democracy or strategy within these mainstream unions, providing a platform through which workers can escape their siloes and risk new forms of coordination. As Allan documents extensively in Organising Workers For Palestine in the Culture Sector, for example, rank-and-file strategy has been significantly revitalised by an influx of militancy around Palestine solidarity organising, increasing connectivity between well-developed social movement programmes and embryonic union campaigns. Often acting well in advance of the trade union mainstream, worker-led initiatives have highlighted the limits and barriers to more militant action amongst culture workers.

What we understand to be the ‘creative economy’ is, of course, only a relatively recent construction. While there are key differences between the worlds of art, music, film, theatre, television, games, and the heritage sector, they are all profoundly structured by the policy decisions of the last four decades, particularly since the Blairite revolution from above. In short, we are living in the wake of a policy approach which attempted to forge ‘culture’ as an economically viable market, deeply integrated into both governance and the wider institutional fabric of Britain at large.3 If officially sanctioned arts were always a cynical means of state and nation-building, then they would also have to become profitable, directly or indirectly, to be deemed justifiable. A highly professionalised sector, complete with its own bureaucratic formations, has developed since. This has involved public-private partnerships producing the infrastructure of galleries, museums, venues, and events within which the workers featured in this issue circulate. The re-adjustment of the economy following widespread de-industrialisation has also rebuilt cities across the country, with cultural activity - broadly construed - used as a means for regeneration. Alongside these infrastructural shifts, creativity and entrepreneurialism have fused to give neoliberalism one of its most seductive ideologies.4 As previous workforces and technical compositions were destroyed, new sectors were built on their ruins, often quite literally. The former militancy of industrial and dockland areas were sanitised and glazed over, from Liverpool to Glasgow, from Hull to London’s Southbank. The promise of vibrancy and prosperity served as a means of dispersing legacies of antagonism, ensuring the ‘creative economy’ could become a platform on which an array of businesses could present themselves as more than just outposts of the retail, hospitality, and service sectors.5

‘Culture’ is a site not only for accumulation - identified recently by the state as a primary ‘growth driving’ sector amongst more generalised stagnation6 - but also a tool for furthering the imperial order. This can be seen clearly with the membership list of the Soft Power Council convened since early 2025. Aligned with the state and the City of London, representatives from groups including the Royal College of Art, the V&A, UK Music, and Historic England are being mobilised as strategic assets in a new front of geopolitical manoeuvring. They are tasked with repairing Britain’s “tarnished brand” on the international stage and act as intermediaries for closer military and political integration.7 The British Museum’s recent attempt to secretly host an “Israeli Independence Day” event on May 13th is the logical conclusion of such a process. Gathered together by Energy Embargo for Palestine and supporting groups, protestors marched on the museum to contest the use of public institutions to launder the Zionist entity, only to be violently penned into a side street by the Met police, as MPs and figureheads of the far-right were left to freely enjoy their ‘genocide gala.’8

Making A Scene (or, struggle and organisation)

The prospects for worker activity in the sector are very much premised on these grand foundations. The entanglement of our everyday working lives with arms companies, the oil industry, and the military-finance complex of banking and logistics is ensured by the state’s active facilitation of investment and agenda-setting within the sector. The standard repertoire of industrial action is not always available to workers in these jobs, and it remains an open question of how diverse practices of withdrawing labour, refusing work, and clawing back power might come together at different levels to sever the control held over cultural production. Those of us employed directly by these institutions may be able to engage in more direct confrontation with the state and funders, as our position as employees opens the gates to strikes and formal trade union disputes (even if this is indeed a relatively rare occurrence). For freelance workers, the establishment of good practice charters and employer payment rates by unions has served as a key line of defense against the widespread hostile working conditions and wage theft in the sector. The growing adoption of these agreements aims to ensure collective uplift and sector-wide compliance - whether through minimum hourly wage standards or expectations that venues adhere to PACBI’s guidelines. However, the ability of dispersed workers to turn these formal mechanisms into grassroots pressure remains an ongoing challenge. Within the patronage systems that dominate much of the art world, workers’ ability to resist the coercive influence of private financiers - who fund exhibitions and gallery renovations - depends on broad mobilisation capable of disrupting the flow of incoming funds. The threat of serious reputational damage, where maintaining a funder risks losing more than they gain, might be coordinated by exhibiting artists, gallery staff and and local organising networks to disrupt operations both internally and publicly. The potential to build effective campaigns across the workforce arises when these distinct sources of power converge. Glimmers of success on all fronts in recent years demonstrate that such coordination is not only possible but increasingly effective.

The facade of a cultural world separate from the vicissitudes of everyday immiseration and political reaction has been shattered for many workers in recent years, and a recurrent set of related themes appear throughout the writing in this issue. The expansion of an intensive managerial culture has amplified the grinding exhaustion of working without sufficient resources and increased surveillance and control, particularly for those on the frontlines. The permanent threat of redundancy and restructuring hangs over our heads, with very little faith present in a bloated managerial strata to defend workers or their interests. This growing disidentification with our institutions of work, so reliant on our creative goodwill, has only accelerated through both the repression of Palestine solidarity organising and the broad institutional appeasement of the reactionary, transphobic Supreme Court ruling.9 The hostility of these spaces toward their own workers, and publics, shows that simply sticking close together with those whom we share a title - curators with curators, actors with actors, technicians with technicians - will not save us, particularly when such positions are being steadily dismantled. The hyper-fragmentation of museum and gallery workforce between subcontractors and outsourcing firms, as Valentin J. and Ethel L. document across Outsourcing Campaigns in Paris, means the sadly predictable division of work along lines of gender and race, and a high turnover of staff. It is only in adjusting to these recomposed workforces that any organising efforts might be successful. When workers become less and less attached to these increasingly hollow institutions, it may only be through a sense of commitment to their co-workers, and a motivating hatred toward their bosses, that they stick around. Or it is when collaborating sectorally that workers discover the strategic power of their own positions, giving renewed significance to organising efforts within their own workplace. As members organising with the Union Syndicale Solidaires demonstrate, engaged workers can collectively make sense of their outsourced status, and gain the necessary sense of mutual recognition to start building a movement across distinct employers.

Two struggles which unfolded in the course of preparing this volume help clarify the stakes of organising across the sector here in Britain. As we began to think about this issue, security guards working at the Science Museum, Victoria & Albert Museum and Natural History Museum initiated a dispute over pay and conditions. Outsourced to large security firm Wilson James, and organised with the United Voices of the World, these workers have taken over 20 days of strike action and conducted a serious campaign of disruption to bring bosses to the negotiating table. They are seeking not only basic improvements to hourly wages, sick pay and extended holidays, but also three legal cases concerning discrimination on grounds of race and disability, victimisation and blacklisting. The jubilant first picket line saw workers and supporters - including many culture workers from nearby institutions - flow into a migrant workers bloc of the anti-fascist march against Tommy Robinson.10 As we prepare for publication, workers at the Royal Academy have achieved significant concessions from bosses during a redundancy program through a whirlwind public campaign, orchestrated with support from the IWGB Charity Workers branch. A large rally at the gates of the RA on March 15th merged into the nearby Palestine solidarity demonstration, again asserting the potential of activity amongst cultural workers when they push beyond the strictures of neatly delineated economistic disputes or solely symbolic expressions of dissent.

The expansiveness of these movements is mirrored all the more intensely by comrades in Cultures En Lutte fighting back against era-defining cuts by Marcon’s government in France. Taking on a format of assemblies gathering across France’s cities, a comprehensive strategy has emerged: one which prepares the fragmented workforces for combative strikes within their own institutions, while also extending creative solidarity into other disputes, from agriculture to logistics. Given their capacity for cultural expression, these workers are in a position to generalise disobedience and antagonism across society at large, contributing ‘subversion and joy’ to the campaigns and disputes of other workers. In this way, the siloing of artists and culture workers is combated by demonstrating the sector’s embeddedness in the broader attack on publicly funded sectors, and that a reversal of budget cuts will need to be won across the board through coordinated struggle. In Britain, the recent mobilisation of arts and culture groups within the fight against cuts to PIP is one vital expression of this intersection. As contributions to a recent open letter by disabled artists clearly establish, the struggle for an open, equal arts world is necessarily a struggle against the state and DWP’s violence toward disabled people.11

At Notes From Below, we have always insisted on the centrality of workers’ own reflection and analysis to make sense of a given wave of struggles or changes in their sector. There has been a surge in workers’ inquiry projects amongst art and culture workers in the last decade or so, helping to shine a light on the difficulty faced by different segments of workers and find points of continuity in their jobs. For example, the US-based Art Workers’ Inquiry group and Britain’s Art Workers Forum both ran inquiry projects to investigate the rapid transformation of working conditions during the pandemic. Reports like Industria’s Structurally F-cked have also drawn extensively on personal testimonies to document the ‘intersecting precarities’ that the racist, ableist and gender-discriminating arts world imposes on artists, and to point toward unionisation and collective identification as the way forward.12 A long lineage of artists and culture workers interrogating their conditions and sites of work is out there to be built upon, particularly when doing so helps toward building resilient organising projects.

Given the relative youth of this sector, however, sustaining an open, (counter)institutional memory of major disputes and experimental forms of activity is an immediate task for anyone organising in these environments. Every fight, victorious or not, helps to produce militant knowledge on how to wage campaigns within the confusing spaces of the cultural sector; as our Fighting Against Redundancies at the Tate suggests of their redundancy dispute during COVID, the ‘best thing that came out of our strike was exactly the legacy’. Lest these insights dissipate into the vaults of trade union bureaucracy or a million disintegrating blogs, new circuits of communication and political centres which expand beyond the usual patterns of artist collectives or cultural networks will be needed. The benefits of these rank-and-file networks, which organise cross-union and between workplaces, is reflected at length in Building the Base. A shared, strategic orientation toward both the sector at large and within our unions can develop when workers gather freely in these groups, helping to collapse the common isolation of creative work, and grow confidence in folding political militancy into union disputes. That this should, as much as possible, occur on an international level is equally apparent. The weakness of funding programmes like the Arts Everywhere Fund, announced in early 2025, underscores the need for sustained, grassroots resistance to austerity and cuts - resistance that would benefit greatly from learning from and building solidarity with parallel movements beyond Britain. The recent, embarrassing pleas for further business partnership and corporate philanthropy from Britain’s major cultural institutions - denouncing in tow the ‘relentless negativity’ that has scared off Israel-tied sponsors like Baille Gifford - reveals a deep lack of imagination from directors and CEOs, and clarifies that the sector’s ‘leadership’ exist only so far as they are personifications of corporate capital.13 By looking to fights elsewhere, and making concrete links with other groups of workers, we can build the confidence that’s needed to take control of our rudderless sector.

Cultures of Revolt

In recent issues of Notes From Below, we have featured writing which has not only considered how workers are fighting to be better organised and empowered, but also what a more fundamental transformation of their workplaces might entail - perhaps even what it might look like in the revolutionary transition to communism. James, for example, writes in Under London in Issue #23, how a “post-revolutionary workplace would surely have to free us from the meaningless guff of human resources” that simply produces authoritarian hierarchy for rail and tube workers. To ask this question of revolutionary transformation of the arts and culture sector is particularly tricky, and there are very real tensions that must be addressed. The abolition of Britain’s major culture institutions - which inhabit and reproduce histories of dispossession and colonial violence, and continue to thrive on these extractive relationships - remains a political horizon that must contend with ongoing organising against cuts and redundancies we see in these spaces. To recreate the means of cultural production, to produce new modes of cultural heritage and engagement, will mean working and struggling through these binds and contradictions. These tensions are channeled particularly acutely in Quit That Job, as Louise Shelley narrates how radical ambitions are consistently stymied by the charity structures and de-politicising systems which arts workers are reliant upon to draw a wage or fund their projects.

Arts and culture cannot be modelled anew from above, through the well-meaning policy advocacy of well-paid directors or the goodwill of academics and researchers. We cannot rely on a tier of professionals or self-appointed leaders whose visions of an emancipatory culture are dislocated from the embodied conditions of the workers who would actually realise their schemes. To approach ‘culture’ simply from the standpoint of ‘good policy’, attempting only to curb and reverse recent neoliberal excess just through the re-directing of funding or tweaking structures of governance, would be to abandon it to technocratic management. It is only through mass contestation from below, organised not by niches, but by a full breadth of workers prepared to fight, that we may begin to glimpse what new cultural work looks like. We know our collective relationship to ‘the arts’ and ‘creativity’ will only be fundamentally altered when capitalism is itself overcome; only when capital’s insistence on exceptionalising, commodifying and individualising creativity and its products is destroyed, can art’s ‘reabsorption into the everyday’ be achieved.14 But, in the meantime, it is through the actions of workers and militants themselves that a different vision of the sector emerges most clearly. Take, for example, Austin Kelmore’s reflection that the experience of building a fighting union, and developing a more militant culture amongst game workers, could radically reorient the types of games being produced, and the new worlds they can envision. Or, Jez’s dream of theatre shows in which all workers involved are recognised and valued, collapsing the toxic divisions between ‘creative’ and ‘non-creative’ workers who bring these productions to life.

The evolving coordination between workers and social movements in efforts to deplatform speakers and events, enforce boycotts, remove sponsorship and funders, and extensively map the sector’s sources of income and investment represent particularly fertile ground for cultivating a radically different cultural landscape.15 Although distinct from those organising with arms and logistics workers to disrupt the war machine, the expertise shared between workers and social movements is the common basis on which effective action is possible, be that in sabotage or strikes. Art, like any other commodity, circulates in the logistical systems of global trade and communication, and these collaborative processes of inquiry into its movements are vital in demonstrating how our labour can be be recovered from the influence of genocide profiteers. A resurgence, too, of occupations and direct reclamation of resources may play a part in this process, as Cultures en Lutte document in France. This might take the form of repurposing venues otherwise hosting millionaire funders for vanity projects, shutting down major events, or directly taking control of sites of work and facilitating access and activity on terms other than individual payment or sponsorship. For a workforce premised on risk and experimentation, these are surely challenges we should relish.

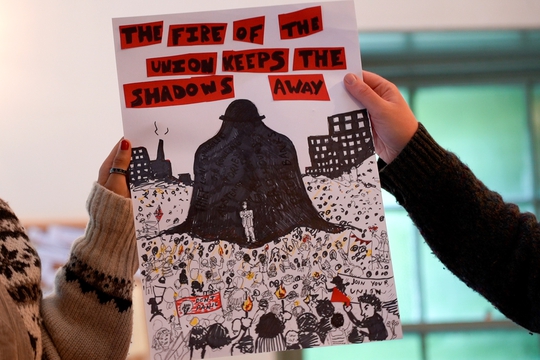

We recognise the imperative of a lively, militant cultural field; well resourced, but untrammeled by the deadening passivity of corporate sponsorship and state sanction. A cultural infrastructure which can both help to combat growing fascism and enliven the social foundations on which a revolutionary movement can flourish and massify - these are basic conditions with which anyone committed to the overthrow of capitalism should be concerned. The capacity for art to articulate the crises of the present, to give form to refusal and rupture, to express the impossibility of reform or reconciliation with the current order, remains always precarious.16 We know, however, that the organised dispassions of art and cultural workers, exploited and enraged by the conditions of their labour and creativity, will remain a prominent force, amongst others, in the compositions of future revolutionary activity. As one worker reflects in The Only Polemic Left In The Art World, the ‘real stakes are here, in these struggles, not at a biennale.’

-

Wages Against Artwork by Leigh Clare La Berge (2019) or Dave Beech’s Art and Value (2015) are two texts to read as a way into these debates. ↩

-

‘Unionism, Diversity of Tactics, Ceaseless Struggle’ in Paths To Autonomy (2022). ↩

-

See Literature and The Creative Economy by Sarah Brouilette (2014) for a useful primer on this process. Read, too, Issue #41 of (the recently returned) Variant magazine for a timely review of this period, as well as its extensive cover over the decades, at variant.org.uk. ↩

-

No Room to Move: Radical Art and the Regenerate City, Josephine Berry Slater & Anthony Iles (Mute Magazine, 2009) ↩

-

See, for example, Neil Gray’s three part series in Variant Magazine (Issues #25, #33 and #34) for an account of “the brutal class politics involved in the re-ordering of urban space” in Glasgow. ↩

-

Invest 2035: the UK’s modern industrial strategy. Department for Business and Trade. November 2024. ↩

-

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2025/01/20/uk-government-flies-flag-for-culture-with-new-soft-power-advisory-council ↩

-

Energy Embargo for Palestine’s account of the protest: https://www.instagram.com/p/DJoypB3IUBP ↩

-

The concrete experiences of navigating and defeating this repression also remains to be more fully documented. Artists and Culture Workers London has recently produced a survey for workers to track the impact of Supreme Court ruling in their workplaces, which can be found on their website: https://artistsandcultureworkers.org/ ↩

-

See @workers.antifascist for documents of this protest. ↩

-

‘Calling Disabled Artists: Help Us Expose the Impact of PIP Reforms’: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1VYBfbf8R3gSQAVK23cHEnJfooQkpQ0Mwzqcyb6ItYSg ↩

-

Structurally F-cked (2023) on a-n.co.uk/research/ ↩

-

‘Letter: One Year On From The Baillie Gifford’ arts sponsorship boycott in the FT, signed by “Sir Alistair Spalding and Britannia Morton, Co-CEOs of Sadler’s Wells, with support from the V&A, British Museum, Donmar Warehouse, National Theatre, National Gallery, Royal Ballet & Opera, Southbank Centre, The Old Vic and Edinburgh International Festivals.”. ↩

-

Henri Lefevbre, Volume II in The Critique of Everyday Life: The One Volume Edition (2014). ↩

-

Think here of the mass coordination of musicians dropping out of Field Day 2025 festival’s programme due to its ties to equity firm KKR, or the editors and writers of Zero/Repeater Books initiating a boycott campaign against parent company Watkins Media for its suppression of Palestine solidarity amongst those at the press, or Energy Embargo for Palestine and Parents for Palestine’s research work. ↩

-

Andreas Petrossiants, Preliminary Notes Toward a Destituent Art (Social Text 2024). ↩

author

Notes from Below (@NotesFrom_Below)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

Organising Culture in the Hospitality Industry

by

James Barrowman,

Cailean Gallagher

/

Aug. 21, 2024