A History of Farmworkers' Struggles

by

Matthew,

Dante Philp

September 21, 2023

Featured in Seeds of Struggle: Food in a Time of Crisis (#18)

An account of farmworker struggles over the last two centuries

theory

A History of Farmworkers' Struggles

An account of farmworker struggles over the last two centuries

Growing food is hard. It always has been, and it will continue to be so for the foreseeable future. In class-based societies, it’s ordinary people who have been asked to do the backbreaking work of feeding everyone else. Under feudalism, food production was mostly the work of a rural class of peasants. But as capitalism started to replace that older system, agricultural work was recomposed. Land was enclosed - literally fenced off - and the old system of common rights to land and strip farming became replaced by something we would now recognise as the predecessor of modern commercial agriculture. That class of peasants were increasingly displaced into towns and cities, where they became the working class that fuelled the industrial revolution. Those who remained worked for wages as a new kind of agricultural labourer - a proletarian who lived and worked in the mud in order to feed the growing industrial populations of cities like Manchester. But despite their central social role, farmworkers in Britain today find themselves marginalised.

How has this happened? We know this situation didn’t appear out of nowhere. Its roots go back through hundreds of years of agricultural struggles. This two-part article attempts to trace some of this history of farmworkers’ struggles. Beginning in the riotous early 18th century, we map the peaks of rural insurgency, as well as their defeat, to present how farmworkers and their organisations have tried to navigate the changing nature of agricultural production over the last two centuries.

Part 1:

Agricultural Class Composition in the early Industrial Revolution

England in the 18th Century was agriculturally unique compared to the rest of the world. This was because, for the most part, it did not have a peasantry, but rather a class of rural waged workers. This was a process of proletarianisation that had been undertaken over a long period of time, and was mostly complete by the start of the industrial revolution. Yet, with the industrial revolution came a further transformation of agricultural work and the workers engaged in it.

Eric Hobsbwam and George Rudé describe the existence of roughly three classes in 18th and 19th Century agricultural England1. At the very top were the landowning class, numbering in the few thousand. These landowners however rarely cultivated their land themselves. Instead, this land was divided up into large plots, of around 100 to 300 acres2, which was then rented out to tenant-farmers. It was these tenant farmers, numbering in the couple of hundred thousands, who would use this land to produce agricultural goods. In order to do this though, tenant farmers had to hire and exploit the labour of millions of farmworkers. Mass enclosure of common land further distinguished these class differences. It not only increased the rental value of land for landlords, but also the dependence of the rural workers on waged farm work.

Of the latter class, E.P. Thompson distinguished farmworkers into four groups3, each with different working conditions:

• Farm servants, hired either annually or quarterly;

• The regular labour force, usually employed the full year round and working on large farms;

• ‘Skilled’ specialists, who were often contracted for particular jobs;

• Casual labour, paid either on a daily or piece-rate.

The casual labour force often included those most marginalised in society. This included women and children4 as well as skilled Irish migrants.5 The regular labour force was itself internally divided between older workers with more secure jobs, such as ploughmen and shepherds, and young workers with much poorer jobs, such as teenage farmhands.

During the Industrial Revolution, rural labour was further proletarianised. General conditions had previously been influenced by traditional values. For example, a workers’ wage often varied by the size of the family they had to look after. However, during the Industrial Revolution, conditions became more influenced by the domination of the ‘market’ over society.6 The migration of many workers to towns and cities, as well as a large growth in the country’s population, led to a massive increase in demand for food. The working population of rural areas also changed. As younger workers migrated, those who remained working on farms were often either very young workers, or older workers, who would be unable to find work in the cities.7

At the same time, the growing population created a continued surplus of labour. Migration from Ireland and the return of 250,000 soldiers from the war in France in 1802 further aggravated this situation.8 Under-employment became a constant feature of life. In many areas unemployment stood at over 60% at certain times of year.9 It was estimated that between 50 to 80% of farmworkers relied on poor relief, in addition to their wages, to survive.10 At the same time, the rising cost of poor relief led to political attempts by the landowning and farmer classes to cut this last form of social security for rural workers.

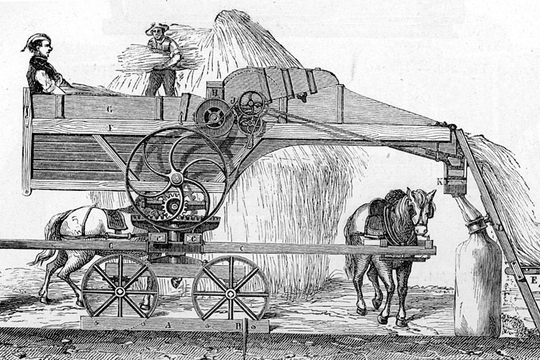

Despite these other changes, until the mid-19th century, little new farming machinery was introduced (with the exception of the threshing machine). What did change, however, was the scale of farming. Wetlands were drained, waste land was converted, and regions were specialised to specific crops - all making English agriculture far more efficient per acre than its counterparts in mainland Europe.11 During this period around a third of farms employed more than six people, and one fifth employed more than ten12, which was also comparatively much higher than in the rest of Europe. Traditional farming and management techniques were still used on these larger farms, although there was some regional variation. For instance, in East Anglia the ‘gang labour system’, commonly known for its use on American slave plantations, was widely employed.

Early Farmworker Struggles

The widespread conditions of underemployment and poverty made rural rebellion increasingly likely. Disputes are recorded as early as 1800, with a group of 300-400 farmworkers gathering in Thatcham to demand either higher wages or cheaper food.13 The breaking of threshing-machines, which would be a concentrated source of farmworkers’ hatred for decades, was recorded in Suffolk as early as March 1815.14 This breaking of threshing machines was not just an act of general resistance, but a direct attempt by agricultural workers to combat underemployment and create more work for the local population. Other forms of criminal working-class resistance grew during this period as well, such as poaching and theft. A first wave of agricultural workers’ struggles - in the form of riots, arson, and machine-breaking - occurred in 1816. It is almost certainly not coincidental that East Anglia, home to the labour gang system, was the place where these struggles took place. In the village of Littleport, over 50 farmworkers met in a local inn to discuss the situation of unemployment and the rising cost of grain. These initial workers then set out and gathered hundreds of other locals, and proceeded to riot throughout the village. Their demands included caps on the price of flour, a 2s a day minimum wage, and for beer to cost no more than 2d a pint.15 These riots then spread to the neighbouring towns. Authorities quelled rioting by offering to increase poor relief and a minimum wage, before then using a local militia and cavalry to physically crush the rioters.16 Unrest broke out again in East Anglia in 1822, during which 52 threshing machines were collectively destroyed by crowds of farmworkers.17

The Swing Riots

It was however in 1830 that the most wide-ranging agricultural worker revolts occurred. This wave of unrest that swept through over 20 counties in the southern and eastern parts of England was dubbed the ‘Swing Riots’. It was named after threatening letters sent to farmers by rural workers, anonymously signed as ‘Captain Swing’. The breaking of threshing machines was the main activity of these riots, with 418 machines recorded as being destroyed nationwide. However, there was also arson, threatening letters, and attacks on overseers. Large crowds also assembled to extract money and food, as well as enforce rent reductions, from the bosses.18 Although the specific demands of the workers involved in these riots varied, the basic aims remained consistent: a liveable wage and an end to rural unemployment.

There had been a disastrous harvest the year before the Swing Riots. Farmworkers then came into 1830 already with a strong memory of being cold and hungry. The past two decades had already seen a squeeze on the conditions of farmworkers, with work becoming more casualised and wages decreasing. Local changes to poor relief only contributed to a growing tension on farms. Reactionary attitudes, such as anti-Irish sentiment, had also increased. Just before the Swing Riots started in Kent, crowds of English workers had forcefully expelled casual Irish workers from the farms they worked on.

Kent was the first to light the spark. Starting with arson attacks on local farms, it moved to more public action with a first threshing machine being broken in a village near Canterbury. A cycle of arson, machine-breaking, and riots, would continue for months. These struggles spread to other counties, organised either by local farmworkers, or by rioting crowds who moved from one area to another.

Local riots were generally started with a meeting to decide demands to present to local farmers. If the farmers resisted these demands, then a group of militant farmworkers would build up the support of a local crowd, using both persuasion or intimidation. They would then move to another farm and “encourage” the workers there to join them. The actual destruction of threshing machines required only a few skilled men - usually a blacksmith or a carpenter - armed with sledgehammers. However large crowds were needed to provide cover for these activities. As the movement continued, riots would often take place in the middle of the day, with a festive atmosphere and public performances. Machine-breaking was a very public form of action, and therefore arson, done in the middle of the night, was more common in areas where the movement was smaller.

Eventually, through a mixture of repression and some concessions to the farmworkers, the Swing Riots came to an end. In the aftermath, almost two thousand rioters were arrested. 19 of these were executed, almost 650 were jailed, and 480 were transported to Australia. These transportations were unusually harsh, being the largest single group of transportees in English history. This shows just how important agriculture was to the functioning of British capitalism at the time, and how destabilising class struggle within this sector could be. Whilst the riots led to an increased pressure for reform, it was also followed by a broader loss of confidence amongst the agricultural working-class. Decades would pass before a movement of similar size and momentum would appear again.

Early Agricultural Trade Unions and the Tolpuddle Martyrs

Whilst for the middle part of the 19th century, a mass movement of farmworkers was not to be seen, on a local level struggles and forms of organisation did continue to emerge. The most famous of these was the struggle of the Tolpuddle farmworkers, who are celebrated each year at the Tolpuddle Martyrs festival.

A group of farmworkers in Dorset, led by George Loveless, went round local villages, setting up meetings with farmers to agree wage increases for farmworkers. In one village, Tolpuddle, the farmers agreed to a 10 shillings a week wage for workers. However, the next year, these farmers went back on their deal, and decreased wages to 7 shillings a week. In response, Loveless and his colleagues set up the ‘Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers’, a trade union for Tolpuddle farmworkers. The local farmers took alarm at this, and in February 1834 put up signs warning workers of seven years’ transportation if they joined the union. This was not an empty threat. Three days later George Loveless, and five other members of the friendly society were arrested. Although forming a trade union had been technically legal since 1824, the Tolpuddle group were charged with an old anti-oath taking law, and were sentenced to seven years’ transportation in Australia.19 In response to their sentence, trade unions began mobilising. An 800,000 person petition was signed, and handed in during a demonstration of 30,000 workers in London.20 Eventually, the government pardoned the Tolpuddle Martyrs, and they returned to England.

More local struggles emerged later in the 1840s. In East Anglia, over 250 arson attacks took place against farmers between 1843-45.21 In West Wales, where the farmwork was more widely done by small freeholders, the ‘Rebecca Riots’ targeted toll gates and landlords between 1839-1843, in protest of the rising cost-of-living. However, this movement was different to those in England, as it was initiated by local farmers. Only later would farmworkers become more involved in these riots.22

Agricultural Class Recomposition in the middle of the Century

Farm work was also changing during this period. From the 1840s onwards, new technology, such as fertilisers and steam-power, was more widely introduced on farms.23 By 1850, only 22% of the British population was involved in farming - the lowest of anywhere in the world.24

In 1845, the corn laws were also repealed. These laws had been originally introduced to guarantee a high price for cereal crops, and support the domestic agricultural market. Whilst these laws had greatly benefitted the landlords and farmers in England, the benefits had not been passed onto farmworkers. Nonetheless, the repeal of the corn laws still had a massive impact on farmworkers. Combined with greater use of steamboats, the repeal of the corn laws meant Britain started importing cheaper grain from across the world. In the 1830s, Britain had imported only 2% of its grain - by the 1880s it imported a huge 45%.

This decrease in the domestic market share on cereal crops led to a decrease in demand for labour. This decrease in demand for crops particularly affected Irish tenant-farmers. Many were evicted from their homes by their (usually English) landlords. Combined with the disastrous and deadly Great Famine, caused by the British government’s policies, migration increased from Ireland to England. Whilst most migrants settled in cities, this still provided a pool of cheaper, experienced farmworkers for farmers to employ during harvest season. At the same time, the agricultural workforce was shrinking, reducing by almost 100,000 between 1871 and 1881 alone.25

The Rise and Fall of the National Agricultural Labourers’ Union

In the late 1860s a new form of farmworkers’ struggles began to emerge. Local farmworkers’ unions began forming, such as in Midlothian in 1865, and Kent in 1866. Increased competition for work also meant there was an increase in migration between rural areas. Workers were then increasingly able to compare conditions in different farms and regions. Food prices were also increasing, making it harder for workers to continue to afford to live. The countryside was looking more and more volatile.

The spark that lit this match was the formation of a union in Wellesbourne, Warwickshire. In 1872, local farmworkers called a meeting, spreading it through word of mouth around local villages. Instead of the 30 individuals they expected, nearly a thousand workers from various neighbouring villages came to the meeting.

A strike was launched in Wellesbourne, demanding 16s wage a week. Around 200 low-paid farmworkers joined. Within a few weeks, membership of the union was at nearly 5,000, and more and more farmers were agreeing to increase wages. The strike set off a wave of unionising across multiple counties.

Soon after, the National Agricultural Workers’ Union (NALU) was formed, led by Joseph Arch, who had helped form the original union in Wellesbourne. Within a year over 70,000 members had been recruited, with a thousand local branches. A number of independent regional unions also emerged. Over the next two years, the national union fought a number of local battles in an effort to increase farmworkers’ wages. To an extent, it succeeded. Wages went up, along with union membership. By 1874 union membership peaked at over 86,000, around 6% of all the farmworkers in England.26 However, the unions’ struggles were generally fragmented amongst many different local farms.

In 1874, farmers in Suffolk began refusing to hire union members. This tactic spread to Lincolnshire, with 6,000 union members being refused any work. Soon farmers across the country were systematically refusing to let any workers onto their farms unless they gave up their union memberships. For many farmworkers, being refused work also meant being evicted from their homes. NALU responded by covering their unemployed members’ wages. However, after a few months they could no longer afford to pay these wages, and many farmworkers had gone back to work. Failure to win this and other struggles over the following years led to a collapse in union membership. By 1881 it had fallen to 15,000, and by the 1890s only 1,000 members remained.27

Part 2 The hidden world of 20th century farmworkers

“The village labourer of the nineteenth century remains a curiously anonymous figure, in spite of the attention given to agriculture, Speenhamland, and Captain Swing. We know a certain amount about his movements…but very little about his life.”28

Raph Samuel’s words have not only proved a challenge to historians of the nineteenth century, but serve as a constant reminder that our understanding of the twentieth century’s farmworker remains equally obscured.29 The history of agricultural production in the 20th century is complex: the post-war policies of mass productivism which prioritised stability; the emergence of European Union law and policy; and a system of trade and consumption upheld by the continued violence of colonialism. But it’s all united by one shadowy figure - the farmworker.

General character of the farmworker’s century

At the start of the century, farmworkers were seen as a backwards section of the working class. Commentators assumed they were incapable of organising for improved conditions or achieving any degree of unity comparable to their industrial counterparts.30 But we must realise that the marginalisation of farmworkers was a very real and modern condition. Farmworkers endured worse living conditions and lower wages than workers employed in the industrial, manufacturing and service sectors.31 The minimum weekly wage of farmworkers in 1948 was just 90s, far lower than the across-industry average of 134s and below that of manual workers, coal miners and dock labourers.32 In 1980 this gap remained, with male farmworkers earning 67.5% of the average wage of all male workers in the UK. A stark gender pay-gap was a constant too, with under 50 % women earning the set minimum wage in 1980, for example.33

Low wages plagued farmworkers despite the emergence of a wages-board system at the beginning of the century. Established as a result of the 1917 Corn Production Act, this board was repealed, reinstated and reworked numerous times, until it was finally stabilised following the 1947 Agriculture Act.34 From this point on minimum wages, benefits and overtime were set in an annual meeting of farmer and worker representatives. Whilst fiercely defended by farmworkers, the wage board was also seen as symbolic of a wider failure by farmworkers to organise at a local level.35 The Scottish Farm Servants Union (SFSU) was, in this vein, to continue to opt-out of the wages board until 1937, when a rapid decline in wages necessitated its late arrival into the system. Suspicious of anything that ‘might take away agency from the farmworker, the SFSU’s president Joseph Duncan resolutely rejected any state intervention around a minimum wage. Instead, he demanded that workers take it upon themselves to impose a higher wage on their bosses through action.36

Farmworkers’ unions had taken an increasingly prominent role in managing the wage, by means of their appointed bureaucracy, through the wages-boards. But farmworkers didn’t just organise around wages. It was housing, and the system of the ‘tied-cottage’, in which workers lived in accommodation owned by their farmer bosses, that came to ‘epitomise the conflict between capital and labour’ within agriculture.37 This system was decried as ‘vicious and anti-social’ in a 1950 issue of The Land Worker38. Farmers mediated farmworkers’ access both to wages and to housing, thereby doubling the insecurity workers faced. Despite the often poor quality of tied-cottages, farmworkers were unable to escape the system due to their low wages, and so they lived under the constant threat of eviction by their bosses. For the farmers, these cottages meant they had reliable access to a pool of cheap labour.39 Despite farmworkers’ hatred for them, they actually became more common in the post-war years as farmworker numbers dwindled, so that by 1975, 55% of farmworkers lived in tied housing.40 In 1969 the Institute for Workers’ Control argued that the system was ‘biggest stumbling block to union militancy and eventual workers’ control’ within agriculture.41

Organising

Farmworkers were often ostracised from the rest of the labour movement in the early years of the century. Labelled as ‘menaces’ and blacklegs, farmworkers on low-wages were often drawn to undermine strikes in nearby urban areas, most famously in the 1912 London dock strike42. The collapse of the National Agricultural Labourers Union (NALU) had led to a period of disorganisation amongst farmworkers and pessimism amongst their leadership, with Joseph Arch’s, founder of NALU, declaring he would ‘never trust our class again.’ However, by the end of the 19th century, there was already a new union in development. The National Union of Agricultural Workers began in Norfolk, and between 1910 and 1913 it led a wave of intense strike action. By 1912 there were 12,000 members across 232 branches.43 Other workers in the sector also joined the Workers’ Union (a general cross-industry union).44

Union density amongst farmworkers always fluctuated, never reaching more than 40% of the total workforce. The NUAW and Workers’ Union both had their membership peak in 1920, at 180,000 and 160,000 respectively, before facing a decades-long collapse in membership. There were many reasons for such poor union coverage, but the entrenchment of the wages-board system has itself been identified as key. Although initially a boon to union recruitment, the wages board was viewed with greater suspicion in later years - after all, why would workers join the union if their wages, albeit low ones, were already guaranteed?45

The formation of a strong rank-and-file movement across Britain was hampered by the seasonal nature of farmwork. Just as much of today’s agriculture relies upon irregular labourers, 20th century farms drew at various points on the labour of local women, children, and prisoners of war and the Woman’s Land Alliance, alongside more itinerant populations looking for work. The transience of farmworkers was particularly acute within Scotland, where workers were far less likely to work on a farm for life. The SFSU was never able to attain the same union density as its English counterparts, and when a merger with the TGWU went to a ballot in 1932, just 1800 members were registered eligible to vote.46 A complex hierarchy existed between the multiple tiers of farmworkers, and the unions were often hostile toward more casualised groups, seeing them as either a threat to the conditions of the traditional farmworker or outside of their interests.47 When many of the 40,000 women still working in agriculture at the end of the Second World War took strike action because they were being demobilised without being given the same benefits as other demobilised workers, the NUAW refused to get involved.48

The Great Strike of 1923

But farmworkers weren’t doomed to remain weak and unorganised. The Great Strike of 1923 in Norfolk was the apex of farmworker activity in the 20th century. The precursor was an earlier wave of strike action that took place in Lancashire, where 2,500 workers fought a bitter dispute in Ormskirk in 1913.49 This strike shaped the agricultural militancy of later years. While the First World War and years after had brought a degree of improvements to the lives of farmworkers, by September 1921 the central wages-board had been repealed. Therefore, just as unemployment bloomed in cities and the post-war boom began to fade, farmworkers began to face an intensification of work, a lengthening of working hours and steadily declining wages. Workers active in the union were most likely to be dismissed, and those who attempted to protest impositions from farmers were often met with lockouts.50

A new generation of farmworkers responded to these declining conditions with an unprecedented level of action. “The agricultural worker of today is waking up” declared The Landworker,51 as farmworkers in Norfolk launched a ‘trial of strength’ against their farmer bosses. These workers were emboldened by the recognition that what happened there would decide what would happen in the rest of the country.52 Having to suffer on wages of just 25s, 7,000 of these farmworkers, some of the best organised in the country, withdrew their labour without notice. In a month-long strike, workers formed cycling pickets, to confront strike-breakers and to spread their strike to farther-flung farms. With a high level of violence and a heightened police presence, the conflict rolled on through stalled talks and failed negotiations, eventually ending in a compromised victory.

Although a success in certain terms - securing the re-establishment of the wages-board in 1924 and halting the wage reductions and lengthening of hours likely to be inflicted all across the country - the longer term effects of the Norfolk strike have often been viewed in a less positive light. While the strike garnered an unusually high level of solidarity from workers outside the countryside, with strike fund contributions reaching £600 per day near the end of the strike,53 the union’s finances were wrecked. Victimisation of striking workers was also rife; despite an agreement that no such blacklisting would occur, farmers still maintained control over who to rehire, and when. At least a thousand striking farmworkers never regained their jobs.54

Rather than helping to foster a new confidence within the union, it instead appeared to mark ‘the end of the union’s career of militancy’.55 A reading of any issue of The Landworker from this period displays a still active union base. There were recruitment drives, compensation was sought from evasive farmers, and there was an active culture of festivals and celebrations. However, the official line was nonetheless to move away from direct confrontation with farmers from this point on. As Reg Groves admits, the NUAW sought only ‘adjustment rather than drastic change’ within the agricultural sector, leaving aspirations of a different, non-capitalist relationship of farmworkers to the land untouched.56

The NUAW’s strategy was to be largely legalistic in character, with officials focused on helping workers to secure themselves against eviction, contest a lack of workplace safety, and fight the common non-payment of wages via the law.57 When compensation was secured through union activity, successes were widely advertised within The Landworker, affirming the NUAW’s status as an efficient service for its members. A policy of collaboration with both the government and the National Farmers’ Union was adopted. Edwin Gooch, NUAW president from 1928, looked towards the struggles’ of industrial workers for an example, preferring a conciliatory attitude toward employers and the government rather than class struggle.58

Post-war transformations

The Second World War swept the industry up in a series of fundamental social changes. The years between the strike of 1923 and the start of the war - commonly labelled the ‘locust years’ in agriculture - were characterised by insecure and precarious employment for farmworkers, as well as a slow and uneven adoption of new technologies in an unsteady market.59 But following the end of the war, there was a period of ‘almost unimaginable change’60 in agriculture. After almost having been starved out due to an overreliance on food supplies from the empire, the state began to focus on increasing domestic production. Machinery and chemicals came to do much of the work once reliant on human labour. Small and middle-sized farms were also replaced by mass indoor-farms and increasingly industrialised units of farmland.61 With output and yields steadily growing, thanks to heavy government investment, the status of the traditional farmworker was bound to be altered. The government and farmers held an official ideology of agricultural productivism and intensified techno-scientific intervention. Labour saving technologies were a priority for the post-war farm, with around two thirds of investment during this period being funnelled into machinery. Crops which required greater labour were increasingly abandoned for those more easily processed by mechanised means. Farm horses were to largely disappear as the age of the tractor took hold, and the labour required for production was heavily reduced.62 Although the Labour party had promised to abolish the tied-cottage since 1906, NUAW union president Edwin Gooch said in 1950 that the party’s inaction ‘strains my loyalty to this great party almost to breaking point’.63 But finally in 1976 the Rent (Agricultural) Act regulated the worst excesses of tied-cottage the system.64

This revolution in agriculture precipitated a rapid collapse in number of farmworkers and the depletion of the countryside, and it was clear that a mass flight from rural life to urban periphery was unfolding from 1955 onward, with little action taken to prevent such a decline. The farmworkers who left were simply never to be replaced. There were close to a million non-family farmworkers in 1945, but by 1990, this was less than 100,00065, and most strikingly, by 1969 only around a quarter of farm holdings were still employing any full-time hired workers.66 In their place, land owner families increasingly came to occupy their farms - from just 36% in 1950 to 69% in 1982.67 Contracted and seasonal workers were often employed to take on the rest of the necessary labour. This decline in the farmworker population ensured that remaining farmworkers were to grow ever closer to their bosses, seeing more of their employers than they did of their fellow workers. Inter-class identification, premised upon shared work, came to replace the ties which had previously bound farmworkers to one another. Strikes became rare, and the proletarian culture of the countryside went into liquidation.68 By the closing years of the century, little remained of either the traditional farmworker or the political forms they inhabited.

In their place, emerged the seasonal farmworker. The Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme was the mechanism for this new generation of migrant workers to enter the polytunnels and greenhouses of British agriculture. Initially developed to allow students to take on seasonal agriculture work, the upper age restriction of 25 was eventually dropped, and by 2009, 21,250 workers were bound to the scheme.69 However, far more migrants than these official figures reveal were coming to the UK from Europe to work on farms. With limited links to a labour movement or government oversight, they came into an economy governed by employment agencies and farmers interested in cheap, flexible labour. In this environment, the gangmasters system was also born anew - almost extinct in the 20th century, gangmasters once again came to mediate access to the pool of migrant workers that farmers now relied upon, just as unrestrained in violence and coercion as their 19th century precursors had been. The wages board system was also to be abolished in 2012, supposedly as it had been made redundant by the introduction of the national minimum wage. Additional benefits and protections of holidays, sick pay and overtime were quietly abandoned. With limited organisation and in a state of isolation from the labour movement at large, the world of the farmworker had in many ways come full circle, with status and conditions akin to that of the early 1900s.

This history of farmworkers and their struggles shows one thing over and over again: the relegation of farmworkers to the margins is a function of power. The challenge today is to understand how the experiments and traditions of the riots and strikes of 1830, 1872, 1923 should guide us in the challenge of organising against capitalist agriculture today.

The decline of the rural working class communities is an immense challenge in the social composition of farmwork. Whereas the farmworkers of the 1800s may have lived and worked together in their local area for decades, today’s workers are far less embedded. Equally, there has been no strike wave since the technical transformation in the postwar period, so we don’t know yet what kind of tactics might be most effective in the new technical composition of modern agriculture. However, despite these social and technical transformations we can probably guess that future farmworker strikes will still retain a focus on being mobile and occasionally using sabotage as a key tactic. And, absolutely, we can learn that unions that rely on partnership and service based models have died, whilst unions that have engaged in intense struggles have thrived. However, this militancy has always come at a cost - victimisation has been a huge risk from Tolpuddle until the present day, and only mass campaigns that have drawn upon the strength of organised workers in the cities have been able to push back against it. Finally, we have to recognise the novel potentials created by a general understanding of an ongoing ecological crisis - there are coalitions now available to farmworkers that never existed before, and we have yet to see the potential that political composition might create. We must demonstrate that a position of marginality, no matter how ingrained, is never inevitable, but is rather a measure of the success of workers’ ability to organise.

-

Hobsbawm, Eric and Rudé, George (1969) Captain Swing. London: Phoenix Press/) ↩

-

Equivalent to around 56 to 170 football pitches. ↩

-

Thompson, E.P. (1963) The Making of the English Working Class. London: Pelican Books ↩

-

Verdon, Nicola (2002) Rural Women Workers: Gender, work and wages in the nineteenth-century countryside. Woodbridge: Boydell. ↩

-

Verdon, Nicola (2017) Working the Land: A history of the farmworker in England from 1850 to the present day. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ↩

-

Clover, Joshua (2016) Riot. Strike. Riot. London: Verso. ↩

-

Thompson. The Making of the English Working Class. ↩

-

Engels, Friedrich (1845) The Condition of the Working Class in England. Oxford: Basil Blackwel ↩

-

Hobsbawm and Rudé. Captain Swing. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Hill, Christopher (1986) Reformation to Industrial Revolution. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ↩

-

Hobsbawm and Rudé. Captain Swing. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Rudé, George (1978) Protest and Punishment: The Story of the Social and Political Protestors transported to Australia, 1788 - 1868. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ↩

-

Peacock, A.J (1965) Bread or blood: The agrarian riots in East Anglia 1816. London: Victor Gollancz. ↩

-

Muskett, Paul (1984) ‘The East Anglian Agrarian Riots of 1822’, The Agricultural History Review, Vol. 32:1, pp. 1-13. ↩

-

For a complete and detailed history of the Swing Riots, as well as analysis of its causes and outcomes, we would recommend Captain Swing by Eric Hobsbawm and George Rude. ↩

-

Webb, Sidney and Webb, Beatrice (1920) The History of Trade Unionism. New York: Longmans, Green and Co. ↩

-

Past Tense (2021) ‘Today in London radical history, 1834: Massive demonstration from Islington in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ (2021) Past Tense. ↩

-

Muskett. The East Anglian Agrarian Riots of 1822. ↩

-

Jones, R.E. (2015) Petticoat heroes: Gender, culture and popular protest in the Rebecca Riots. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ↩

-

Hobsbawm and Rudé. Captain Swing. ↩

-

Overton, Mark (1996). Agricultural Revolution in England: The Transformation of the Agrarian Economy 1500–1850. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↩

-

Kirkwood, E.R.C. (1992) England: 1870-1914. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ↩

-

Jones, E. L. (1964) ‘The Agricultural Labour Market in England, 1793-1872’, The Economic History Review, Vol. 17:2, pp. 322–338. ↩

-

Groves, Reg (1981) Sharpen the Sickle: The History of Farm Workers Union. London: Merlin Press ↩

-

Samuel, Raphael ed. (2016 [1975]) Routledge Revivals: Village Life and Labour. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ↩

-

Verdon. Working the Land: A History of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day. ↩

-

Howkins, Alun and Verdon, Nicola (2009) ‘The state and the farm worker: the evolution of the minimum wage in agriculture in England and Wales, 1909–24’, Agricultural history review, Vol. 57:2, pp.257-274. ↩

-

Howkins, Alun (2003) The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ↩

-

Verdon. Working the Land: A History of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Groves. Sharpen the Sickle: The History of Farm Workers Union. ↩

-

Griffiths, Clare (2007) Labour and the countryside: the politics of rural Britain 1918-1939. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Newby. Tied cottage reform. ↩

-

You can view issues of the Landworker at: www.mrc-catalogue.warwick.ac.uk/records/AAW/4/1/1 ↩

-

Newby. Tied cottage reform. ↩

-

Howkins. The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. ↩

-

Hillier, Nick ‘Farmworkers’ Control’, Institute for Workers Control ↩

-

Griffiths. Labour and the countryside: the politics of rural Britain 1918-1939. ↩

-

Groves. Sharpen the Sickle: The History of Farm Workers Union. ↩

-

The Workers’ Union later merged with the TGWU in 1929. ↩

-

Hillier. Farmworkers’ Control. ↩

-

Griffiths. Labour and the countryside: the politics of rural Britain 1918-1939. ↩

-

Debates, too, about whether farmworkers should remain in their own union or struggle alongside the worker’s movement at large persisted for the first half of the century. ↩

-

See also: www.suffolkarchives.shorthandstories.com/soil-sisters/index.html ↩

-

Mutch, Alistair (1982-83) ‘Lancashire’s “Revolt of the Field”: the Onnsldrk farmworkers’ strike of 1913’, North West Labour History Society, Vol. 18. ↩

-

Groves. Sharpen the Sickle: The History of Farm Workers Union ↩

-

Groves. Sharpen the Sickle: The History of Farm Workers Union. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

ibid. ↩

-

Griffiths. Labour and the countryside: the politics of rural Britain 1918-1939. ↩

-

Howkins. The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. ↩

-

Verdon. Working the Land: A History of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day. ↩

-

Winter, Michael, Brassely, Paul, Lobley, Matt and Harvey, David. The Real Agricultural Revolution: The Transformation of English Farming, 1939-1985. Martlesham: Boydell & Brewer. ↩

-

Howkins. The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. ↩

-

In technical terms, the labour hours per acre of cereal farming fell by eight times from 1950 to 1983, and the labour hours per acre for potato farming by five. ↩

-

A development eventually achieved through efforts spearheaded by the NUAW’s General Secretary Reg Bottini and Labour MP Joan Maynard. ↩

-

Howkins. The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. ↩

-

Winter et al. The Real Agricultural Revolution: The Transformation of English Farming, 1939-1985. ↩

-

Verdon. Working the Land: A History of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day. ↩

-

Howkins. The death of rural England: a social history of the countryside since 1900. ↩

-

Verdon. Working the Land: A History of the Farmworker in England from 1850 to the Present Day ↩

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next