Grassroots organising with the support of a Big Union? Reflections on Unite Hospitality

by

Megan De Meo,

Will Bright

August 21, 2024

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

Megan and Will, members of the Unite Hospitality branch, discuss the urgent need for organising within the industry. They examine the benefits and challenges of unionising through larger unions like Unite, emphasising the need for a grassroots approach.

inquiry

Grassroots organising with the support of a Big Union? Reflections on Unite Hospitality

Megan and Will, members of the Unite Hospitality branch, discuss the urgent need for organising within the industry. They examine the benefits and challenges of unionising through larger unions like Unite, emphasising the need for a grassroots approach.

Hospitality workers need to be organised, and urgently. It is the third largest sector of employment in the country, and is set to continue growing - the current projections show it growing from 3.5 million workers now to 4 million by 2027. The need for organising, as well as the difficulties organisers within the industry face, lie in the shadow of that growth. From what industries are those additional 500,000 workers supposed to come? For many of them, the move to hospitality will be a forced one, and likely one that will make their living conditions more precarious.

As hospitality workers and organisers based in Brighton and Hove, we have spent the last year trying to organise with our fellow workers. We are members of Unite Hospitality, whose South-East branch opened early in 2023. Here we use our experiences to debate the values of organising as part of a larger union or as grassroots organisers, in the hopes that our experiences can be useful to other workers seeking to organise within hospitality or other precarious and unorganised sectors.

The future of the working class

If you care about the future of the working class, then you should care about working conditions in the hospitality sector. We are some of the lowest-paid workers in the economy, and we are contracted under some of the most precarious conditions. Problems in the sector are widespread and well-known: the absence of health and safety practices, sexual harassment, unsociable hours, and abusive customers and bosses. Whilst these issues should - and sometimes they do - agitate the workforce, they also create the conditions that mean those workers are hesitant to take any action. It is difficult to inspire a worker who is downtrodden, told constantly that their labour is unskilled, and sees this reflected in their payslip each month. We need a national movement that is able to mobilise workers at scale, to inspire hospitality workers to take action. We need to demonstrate that our working conditions do matter, that our labour is valuable, and that we are capable of bringing about change.

These issues faced by workers in our sector will only be rectified by organising workers on a workplace-by-workplace basis. In a sense, the union that any worker chooses to join matters less than how she can interact with her colleagues. Union officials do not win strikes, workers must be able to win in their own workplaces. However, it is important that Unite Hospitality is already winning significant gains - from securing the living wage across five ItIsOn venues, to £200k in unpaid wages for sacked workers at Virgin Hotels - these workers are experiencing the benefits of being part of a trade union. Whilst much of this is concentrated in Scotland, it does show that the model can work. There are now Unite Hospitality branches across the UK & Ireland, and Unite is investing in hiring full-time organisers to support them, which means that the Scottish model can be replicated elsewhere.

Workers within Unite have been winning at work - during the cost of living crisis our members have consistently won inflation-busting pay rises. This was never inevitable, and came as a consequence of an active shift in policy with the leadership of Sharon Graham which prioritised workplace organising. This is reflected in the increase in the annual amount spent on strike funds - which has shot up from approximately £1.1 million to £15 million. Comparable shifts in policy have been made in other unions: the work of members, including the grassroots groups NHS Workers Say No, in the RCN brought about the first nurses strike in the history of the organisation - an idea that would have seemed inconceivable a few years ago.

Often the temptation for young socialists is to join small trade unions, that tend to be more radical, and to organise on a grassroots basis. When deciding what kind of union to join, I think it is important to remember that in order for workers to win inflation-busting pay rises with Unite, or to take the RCN from a membership organisation to a union, members and staff within those unions had to fight to get to that point. And while it is so often frustrating to struggle both against your boss and the union that represents you - if you do take these struggles on, the wins will be worth it.

We have to do it ourselves

Organising has always started from the ground up. In hospitality, we are facing a situation in which it once again needs to happen from below. It was, after all, grassroots organising that formed the unions that would become Unite and the other large union amalgamations. While larger unions can offer resources and training to grassroots organisers, they cannot anticipate and appreciate the particularities of sectors in which they have had comparatively little experience.

Hospitality workers know better than anyone the challenges they face in their working lives. Whether it is the constant struggle to balance the need for long, underpaid hours with the instability of zero-hour contracts or the indignity of harassment from customers or management, these workers know that their work undervalues them and are told to accept that as a natural consequence of their labour being “unskilled.”

There are barriers to starting the organising process within the hospitality sector that can only be addressed by organisers who understand these barriers firsthand and have had to overcome them themselves. Arguably the most daunting barrier is the historic lack of organisation within the sector. The unions that formed Unite in 2007 had existed for decades by that point and represented sectors in which unionisation has historically been on the table for workers. Hospitality doesn’t have that luxury. At this point, getting workplaces organised should be the primary aim of grassroots organisers. Any workplace that is organised, whether an independent pub with ten workers or a national chain of restaurants, should be considered a significant win by the trade union movement. This is at odds with the priorities of larger unions, which tend to focus on larger workplaces where larger wins can be achieved with a little more ease.

Why is it so important that grassroots organisers understand the industry firsthand? Hospitality is a precarious industry. It doesn’t have to be, but has been systematically made so by decades of legislation intended to benefit employers and which has greatly weakened the bargaining power of workers. Hospitality workers understand the psychological impacts of precarity in their bones. Precarity is stressful. Zero-hour contracts mean that no worker is guaranteed a set schedule, or knows what their pay will be until the cheque comes through. A worker’s rota might come through two weeks ahead of time, or one week, or two days. Hospitality workers are frequently on unsociable hours that, given a lack of a set schedule, can make healthy sleeping patterns almost impossible to keep up. Shifts themselves are often stressful - how many hospitality workers are kept from legally mandated breaks or put on to work in the morning after closing the night before? How many rude customers do we expect workers to simply shrug off? This stress is mental, and it is physical.

Organise everywhere

A joyful aspect of organising in this sector is the conversations with others who have worked in hospitality. It is not all stories of bad bosses and unfair contracts - I often hear “it was the funnest job I ever had.” Clearly, many workers work in hospitality at some point in their lives. This is often during their late teens or twenties, and acts as a formative experience of the first instance of degrading, repetitive work. This experience also comes with the comradery of doing hard work in a hectic environment, that is often at the heart of the community it is situated in. This means that organising the sector offers the opportunity to raise the class consciousness of millions of workers every year. These workers will go on to move into new careers, with the experience of union activity. To radically alter the living conditions of the working class, we need joining a union to feel like a common sense - and unionising hospitality can be an important part of that project.

Organising precarious workers - on a scale that will bring meaningful change to the industry and build resilient working class power - is resource intensive. Over the last year, we have spent countless hours visiting workers in bars and restaurants, and having conversations about their working conditions. This work was worthwhile, and has done a lot to raise the profile of the union in the city - but during that time we only signed up one workplace to the union. It takes a huge amount of time and energy to move people to the kind of action that will bring about change at work. As hospitality workers, we need to embed ourselves in unions big enough to provide us with the resources necessary to do this work, and to take part in the democratic decision-making processes to secure these resources.

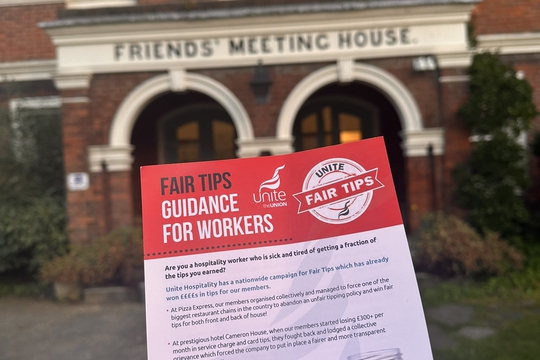

One area that requires the resources, and the structure, of an established trade union is the unionisation of workers in national chains. Chains like Starbucks or Wetherspoons should be a target - they make eye-watering profits by exploiting their workforce. To be able to coordinate action at these workplaces nationally, membership in a union like Unite is vital. An example of this is the recent fight over tips at Miller & Carter, which was against a tipping policy that meant that serving staff owed the equivalent of 2% of all takings to the back of house - even if they had not been tipped on that order. This meant that there were instances when workers were earning less than minimum wage. Organisers and members of Unite Hospitality responded by reaching out to workers, which led to a grievance being raised at eight workplaces thanks to the tireless work of our members at those stores. This was able to happen due the nationally co-ordinated response, and the distribution of flyers at numerous stores, which were sent to members through the Unite Hospitality structure.

The aim is not to organise one workplace, or workers within a single city, or even an entire national chain. The aim of this project has to be to empower all workers within hospitality. We are now in a period of climate change-related inflation. For the rest of our lives, access to the resources we need to live will be restricted further and further. Essentially, we are all fighting over an ever-shrinking pie. The correct response to this - alongside fighting for policies that mitigate climate change - is increasing the strength of workers, particularly those who work in sectors with historically low union membership. If we are to take on this fight, we need to be able to organise at scale, and we need the structure of a national union in order to do so.

The contradictions within our union

Our experience of organising under the umbrella of Unite Hospitality has made us keenly aware of some of the issues facing grassroots workers who look to larger unions for resources and training. The sheer size and scope of Unite’s activities means that there are levels of bureaucracy geared towards helping workers in organised workplaces that can actively impede resources going to workers attempting to organise their own workplaces.

Organising is resource-intensive. On the part of the organiser, it requires a significant time commitment, as well as emotional labour to navigate the challenges in organising precarious workers that we have already mentioned. Most of the grassroots organisers are volunteers, and the commitment they make comes with no material compensation. They are often already radicalised enough to see the longer-term benefits of their own individual contributions to a larger movement, and stressed enough by their own work to want these benefits sooner rather than later.

Many in hospitality work within smaller workplaces, independent businesses or for smaller local chains. For larger unions, investment of resources is often decided on the size of a workplace - the bigger the better. In the time we have been working with Unite, we have been told several times that the general minimum number of workers - or worse, members - for the union to consider investing resources in a workplace is around ten. How can this translate to a sector filled with these smaller workplaces where ten is often the maximum number of workers at any given time? More to the point, hospitality workers are told implicitly and explicitly that their work is less valuable all the time. The last place they should face that kind of indignity is from a trade union.

Grassroots organisers could definitely use training to help get a handle on a task that can, itself, seem overwhelming. However, this training does not have to be tied to larger unions. There are courses available on organising, such as ‘Organizing for Power’ run by Jane McAlevey, that educate grassroots organisers based on direct experience. Whilst this training is developed with workers in healthcare or education in mind - who tend to have access to union resources - it is one example of how workers might access training without jumping through the bureaucratic hoops of the trade union. Or without having to book a week off of work to attend training developed for workers in workplaces with recognition agreements. The point is, we are part of larger social movements who have often developed the knowledge we need to transform our workplaces. If grassroots organisers are looking for relevant training, why not do so freely and outside of the bureaucracies of larger unions?

The final point here is particular to Unite. Unite operates regionally; it has branches for set regions of the UK. In Brighton and Hove, we are members of the Unite South East branch, which extends up to Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Members in Brighton and Hove who are active within Unite Hospitality are therefore given the impossible task of organising in, say, Oxford, without a knowledge of the area or the people there, and without proper training. Thus the work of organising across workplaces and across counties becomes a new point of stress for workers, and the areas of the South East without the radical volunteers already there remain unorganised. The kind of grassroots organising we need has to be guerilla in nature, flexible and manageable. At the beginning of this project we aimed to reach out to 800 members across the region. Whilst this did lead to some engagement with the branch, the outreach with far greater results has occurred where we have taken advantage of organic relationships we have locally with other hospitality workers. As mentioned above, the structures of a national union will be needed in order to organise at scale within this industry. This must, however, start with organising that is anchored within local communities.

Where does that leave us, the hospitality workers desperate for better working conditions, better pay, and better treatment? For us, it means continuing to organise within Unite Hospitality - which affords us the possibility of being part of building a large movement - whilst recognising the limitations of organising with a union which was not developed for workers like us. We will address these limitations in two ways: by engaging in the democratic structures of the union to fight for the resources we need to transform our industry, and by looking elsewhere - within wider social movements and our local communities - to find the support we need to take on the fight at work. Just like workers in any other trade union, we should expect representation in disputes and within the union, as well as access to the funds needed for day to day organising expenses (for hiring rooms, printing flyers etc.). In an industry as challenging as ours, we must also argue for additional resources - including tailored training and staff time - to ensure that members are supported to win within their workplaces. And like any workers, we need to know when to turn to our communities and the wider working class movement for support, including lessons learnt from other struggles.

We are left needing to build a social movement, of which larger unions will play a part, but which by rights should be led by hospitality workers and organisers. If we want to see this sector changed in the ways it needs to be. Hospitality plays a huge part in the day-to-day lives and social reproduction of people across the country and the globe, and it deserves to be seen as an industry worth the same respect and stability as any other.

Featured in Shift Patterns (#21)

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Afters: Building a Hospitality Workers’ Movement in Glasgow

by

Nick Troy,

Odhran Gallagher

/

Aug. 21, 2024