Fighting Against Redundancies at the Tate

by

Cristina Petrella

August 22, 2025

Featured in Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture (#24)

In the summer of 2020, Tate Galleries faced one of the longest industrial disputes in sector’s history. This interview reflects on the shape and legacy of this dispute

inquiry

Fighting Against Redundancies at the Tate

by

Cristina Petrella

/

Aug. 22, 2025

in

Dispassions: Class Struggle in Arts & Culture

(#24)

In the summer of 2020, Tate Galleries faced one of the longest industrial disputes in sector’s history. This interview reflects on the shape and legacy of this dispute

In this piece, Notes from Below interviewed Cristina Petrella, a former Tate Enterprises worker and PCS Branch Chair, who was involved in their 2020 strike and campaign against redundancies.

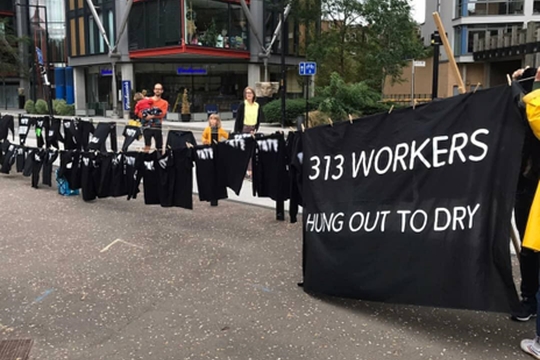

In the summer of 2020, Tate Galleries faced one of the longest industrial disputes in sector’s history when its commercial arm, Tate Enterprises Ltd - responsible for retail shops, cafés, catering, and publishing across Tate sites - announced plans to cut 313 jobs in response to COVID‑19 financial constraints. Workers, unionised with Public and Commercial Services (PCS) Union picketed multiple sites (Tate Modern, Tate Britain, etc.) and received widespread support from over 300 artists in an open letter in solidarity. The strike continued for 42 days until early October, when negotiations mediated by ACAS led to an “improved offer”. On 1 October 2020, the PCS suspended the strike pending final agreement details.

The reflections contained within this interview are more important than ever, as Tate workers fight against and endure another wave of compulsory redundancies, aiming to cut 7% of its workforce, announced in March 2025.

How long did you work at the Tate, what did you do and how did you get involved in worker-organising there?

I started working at Tate in the bookshop in 2011 and became a union representative around 2015. For a time, I was responsible for the exhibition shops, and later I moved to the main bookshop, where I oversaw the art history, art theory, and critical thinking sections. I was primarily based at Tate Modern but also worked at Tate Britain as a casual financial cashier.

In hindsight, working across both sites was helpful in my role as a union rep — it gave me a broader perspective and helped bridge the gap between the two locations. That connection was valuable for building solidarity and improving communication among staff across the different Tate sites.

In 2020, the “Tate Enterprises” - which runs the Tate’s retail, hospitality and publishing divisions - announced 313 redundancies. This was almost half these divisions’ entire workforce. Tate workers responded by going on strike through their union PCS. How did this strike start?

When the shops closed due to COVID, one of our members set up a WhatsApp group for all the shop staff. It wasn’t our idea, and at the time I didn’t think much of it — it just seemed like a social thing, a way to stay in touch and check in on each other. But looking back, it became instrumental in our organising once our situation worsened. It helped us stay connected as a collective, even though we were physically isolated and working from home or furloughed. It wasn’t just union members in the group either; it was open to everyone. We used it to share information, discuss union developments, and offer support. That space helped us maintain a sense of solidarity and mutual accountability during an uncertain and isolating time.

Even before redundancies were announced, early after the lockdown, we were already fighting to get furlough pay extended to all staff. We had just brought in many new temporary workers to prepare for the Andy Warhol exhibition, and at first, Tate wasn’t going to offer furlough pay to all of them. As union reps, we pushed back — and we won. In the end, everyone received the furlough salary. It was a significant early victory.

We continued to meet regularly, remotely. Then, in June, Tate announced that it would be making redundancies across its commercial operations. The message was clear: during COVID, when we were no longer generating revenue, we had become expendable.

Of course, redundancies happen all the time — this wasn’t new. But what was different was our response. As workers, we made a collective decision: we refused to play the role assigned to us — passive, silent, and compliant. We said no. We would not quietly accept a process that treated us as disposable.

Some of us were already politically engaged or involved in protest movements; others had no experience of activism at all. Many of us were artists — some paid, others unpaid or unrecognised — but all of us knew injustice when we saw it. And we understood that if you don’t fight back, you allow the injustice to define you. We weren’t going to let someone else write our story. If we were going down, we would decide how.

When Tate began the formal redundancy consultation process — a tightly timed legal procedure — we were forced to juggle two roles as union reps: on one hand, ensuring the process was fair for those affected, and on the other, fighting the process itself. We held long, open meetings with members where we broke down the situation in detail, talked through the legalities, the risks, and our options. We discussed different forms of protest. In an unofficial preliminary vote, a majority supported strike action. We proceeded to a formal ballot — and the result was overwhelming. Our members voted to strike.

Tate had underestimated us. They didn’t expect such collective resolve — and their own hypocrisy only strengthened our unity. This was an institution that prided itself on being progressive. During the pandemic, they projected “THANK YOU KEY WORKERS” in huge letters across the side of Tate Modern. And yet not long after, they were letting hundreds of workers go, simply because we were no longer profitable. We were also one of the most diverse parts of Tate. There was deep irony in that. An institution that claims to champion artists and creativity failed to recognise that most of its workforce were artists — working-class artists from diverse background who took jobs in shops, galleries, and cafés to support their creative practice. Often these were the very people employed in the lowest-paid roles in the institutions that supposedly exist to celebrate art and culture.

This moment also raised bigger questions about what — and who — the “art world” really is. Who gets to belong to it? Who is visible, and who is erased? In modern neoliberal institutions, it’s time we took a 360-degree view and acknowledged the labour behind the scenes — the workers without whom the institution simply wouldn’t function. From shop and café staff to cleaners, technicians, and front-of-house teams, these workers aren’t peripheral. They are essential. They are part of the machine — and they deserve recognition, rights, and respect.

What role did the identity of being an “artist” or “culture worker” play in your struggle? Did you find any difficulties during the strike in uniting different sections of the workforce?

Every protest or demonstration isn’t just about the action itself — it’s also about the symbols behind it. Because so many of us were artists and culture workers, we were able to bring that creative energy into the protest, making it more visible, more alive, more universal. Take the placards we made, for example — they weren’t just signs; they became a powerful way to communicate our message quickly and clearly, often reaching further than any speech or news article could. Those images spread across the media and helped shape the story on our own terms.

I remember the first day of the strike, the first demonstration outside Tate. We were just standing there, holding placards — looking like a typical, old-school protest. Then, in the debrief meeting afterwards, we asked ourselves: “How can we make our fight more visible? How can we get our message to travel?” That question sparked so many ideas, and as the strike went on, we began putting them into action.

And that ties into something deeper about museums. So much contemporary art begins as protest — a challenge to the establishment, a refusal of the status quo. But once those works enter a museum, their rebellious edge is often dulled, their meaning softened or even erased. Duchamp is the classic example: now it’s a prized piece in the Gallery, but at the time it was a radical gesture — a real protest against the art world’s rules.

In a way, our strike was reclaiming that spirit — bringing protest back to the point where art and everyday labour meet. Our identity as artists and culture workers wasn’t just context; it was central to how we resisted, how we made ourselves seen.

And I suppose Tate failed to understand — or refused to accept — that the workers were artists too, and that we were using our art to protest what was being done to us. That’s part of why our action became so visible — and so powerful.

After an initial five days of strike action, you decided as workers to go on an indefinite strike. Indefinite strikes are quite a rare occurrence these days, particularly in the cultural sector. How and why did you make this decision?

You’re right — an indefinite strike does sound like something from the past century. And honestly, so does striking over redundancies. These kinds of actions feel almost out of place in today’s cultural sector, where precarious work is so normalised that resistance can seem unrealistic. But that’s exactly why we did it.

At the beginning — even somewhat naively — I think many of us believed that going on strike, even just for a few days, would be enough to get results. We hoped that by showing our collective strength, the institution would listen. But those first days passed, and no meaningful change came. Meanwhile, the redundancy process continued in parallel — including a so-called “selection exercise,” essentially a test used to determine who would keep their job and who wouldn’t.

This happened while we were still in the middle of deciding how to escalate our protest. And at that moment, Tate announced the outcome — who was staying, and who was going.

They assumed that once people knew they were safe, they’d stop fighting. That individual security would override collective solidarity. But the opposite happened. It galvanised people. Those who had been told they were safe became even more committed — not because they had to, but because they wanted to. Because they saw their colleagues being treated unfairly and refused to walk away from that.

In that regard, our casualised commerce staff played a crucial role in the strike. Their involvement was instrumental — not only were they an integral part of the protest, but they also refused to accept calls to work during the strike, standing in solidarity with permanent and temporary staff alike. That unity was key to the strength and success of our 42 days of action.

During that time, we often heard from the institution that “we were all in this together,” referring to COVID. But part of our strength as workers came from realising that, in fact, we weren’t. As employees of a subsidiary company, we were treated as disposable. We were excluded from that supposed “togetherness.” In some ways, what we were doing was reclaiming our place in that “family” — not as an afterthought, but as an essential part of it.

That was the moment we decided to escalate to an indefinite strike. Not because it was easy — it wasn’t — but because we weren’t ready to let it go. We weren’t done. We weren’t just fighting for our own jobs anymore. We were fighting for the principle that no one should be discarded simply because they’re no longer profitable to an institution that claims to value people and culture.

You used some innovative tactics during the strike - such as organising exchanges between strikers at Tate’s central London sites and strikers at the Tate’s distribution warehouse further away in Essex. You also at points ran a zine stall on your picket line. How was the strike and all these various aspects of it organised?

It’s important to remember that it wasn’t just about the people in the shop. Warehouse workers were part of our retail unit, as was the publishing house — and many of them were artists in their own right. Around ten years ago, the warehouse team had been based at Tate Britain, until they were dislocated and moved further away. That physical separation made it even more important that we organised regular meetings between workers across all sites during the strike.

Especially before, during, and after COVID, as union reps and safety reps, we spent a lot of time in the warehouse — talking to members, checking conditions, and making sure everything was in place to keep people safe. That work helped build trust and solidarity.

We were a hefty union. Our membership surged during the fight for full furlough at the start of the pandemic, reaching nearly 100% density in our bargaining unit. Health and safety concerns — particularly in the warehouse — played a huge role in that growth.

With so many members, we held large general meetings over Zoom, often with around 100 people in attendance. These weren’t just check-ins — they were in-depth sessions lasting two or three hours, where we broke things down and made key decisions together. And of course, we also met on the picket lines and at protests.

That’s the thing: the strike itself was only one part of it — maybe not even the most important part. The real heart of it was the daily demonstrations during the picket lines, no matter where they were — at Tate Britain, Tate Modern, or eventually the warehouse too.

The picket lines were where we figured out what to do next, and where we planned actions. Like the time we decided to hang all the Tate T-shirts — that didn’t just happen spontaneously. It was thought through and coordinated even logistically.

We also formed various committees — small WhatsApp subgroups, each with a different focus. One worked on planning protests, exploring performative ways to express our struggle. Another managed social media. We had groups for the website, the zine, the podcast, and one dedicated to producing images and placards.

As union reps, we joined remote talks across the country — in places like Edinburgh and Manchester — to share our story, build solidarity, and encourage other workers. We launched a GoFundMe to help sustain somehow the strike, and published regular updates at every event. The campaign received wide support — from members of the public, artists, and even Tate members.

People joined subgroups based on their background or interests, contributing where they felt strongest. It was a true collective effort — almost like a revolution. Like partisans. Not everyone can be a fighter; sometimes poets need to be poets, because their words are part of the fight too.

A modern workforce is made up of diverse specialisations and backgrounds. But it can only survive — and resist — as a collective if it remains capable of setting aside those distinctions when necessary. That is the moral, not just technical, meaning of every mobilisation: a workforce that is no longer available for collective action, or that loses itself entirely in specialised roles, becomes compromised.

At some point, intellectuals, workers, artists — all of us — must be willing to use our experience for the common good. Each of us has to be ready to take our place in active resistance.

In the end, the employers said they couldn’t ask the government for more money to save the jobs because Tate Enterprises was a commercial company. How do you think the split between public and commercial funding in cultural institutions affects workers’ power in the sector?

It’s important to say that the split between the public and commercial sides wasn’t just an abstract idea — it had already been made real well before the redundancies were announced. Even before that, differences in rights like pensions, wages, holiday allowances, and sick pay separated the two workforces. This divide became even clearer in 2020 during COVID, when gallery staff were protected, but over 300 of us from shops, publishing, commerce, and restaurants faced redundancies. That split shaped our protest too — because we felt utterly betrayed. Tate treated us like a dead branch they could just cut off, even though we were bringing in so much of their income. We got so little in return, and the moment we stopped being useful, we were discarded.

But on the ground, there was a strong solidarity between workers across those artificial divisions of “public” and “commercial.” Management didn’t understand it, of course. But our colleagues did, because they were one of us. Ticketing staff, gallery assistants, even curators — they got it. We shared the same pressures and the same sense of injustice.

That’s the irony. So many of the artists featured in these institutions didn’t come from privilege. Their work was rooted in protest and struggle. You’d have retrospectives about them in the galleries, talking about how protest shaped their lives and work. We’d be running kids’ workshops on how to write placards, selling books on protest history in the shop — and yet the institution couldn’t see that we were living that same fight. Working-class artists and art workers engaging in protest in real time — not as an exhibition, but as a necessity.

That’s management’s weakness. They live in their bubble. They impose the split from above, but they can’t see the unity rising from below

You ended up being on indefinite strike for 42 days. How did the strike end?

The situation was brutally challenging. With the looming threat of another lockdown—which indeed came just months after our strike ended—the pressure became overwhelming. Many of us were pushed to our absolute limits physically and mentally, some genuinely fearing they wouldn’t survive the coming storm. Financial support was scarce, and the daily struggle to endure while maintaining the strike took a heavy toll on everyone.

When management’s offer finally arrived, it forced us into an impossible choice. Refusing wasn’t realistic, but accepting didn’t come easily either. We held democratic discussions, with passions running high on both sides. Some members felt accepting would betray our struggle, while others argued we had reached the limits of what was sustainable—that, imperfect as it was, the offer represented real gains worth securing.

After 42 gruelling days of industrial action, we suspended the strike on October 1, 2020. Tate had moved significantly from their original position, yet the final agreement still carried the bitter sting of compromise. Job losses remained unavoidable — a painful concession after fighting so hard to protect every position. This outcome, though improved, served as a reminder that even our strongest collective action operates within the harsh constraints of an unequal system.

How do you see the legacy of the 2020 Tate strike on culture worker-organising - both at the Tate and in the wider culture sector?

I believe the most important outcome of our strike wasn’t just the immediate result, but the legacy it created. Many times, I thought of us as the canary in the coalmine. But perhaps we weren’t. While our situation did signal what might come, it also forced other institutions to realize the consequences of treating their workers poorly. That, I think, is the real impact—not necessarily the outcome we initially wanted, but a crucial outcome for workers across the sector.

I don’t think anyone—neither Tate nor any other institution—expected such a strong reaction to their redundancies. Our protest became difficult for Tate to manage and clashed with their carefully cultivated reputation. They knew they were losing that battle.

Other institutions saw what could happen when they treat some workers with disregard. It made them reconsider how they handle redundancies—often opting to mediate more, offering voluntary redundancies first, and treating compulsory redundancies as a last resort.

So maybe we weren’t the canary in the coalmine after all. Instead, once we began protesting, we became an example of what could go wrong for institutions that treat workers as disposable. And for workers, we showed that resistance is possible. We proved that the strength of workers lies in refusing to accept injustice. Perhaps we also demonstrated how to connect the long-standing workers’ struggles of the past century to the realities of organizing in today’s digital and social media era—making worker fights more relevant than ever.

There’s also another positive outcome worth mentioning. At Tate, many gallery workers were initially casually employed through third-party subcontractors. After our strike, these workers were brought in-house, which was a real step forward.

That’s really interesting. I think this speaks to something we often talk about at Notes from Below, which is how class struggle changes not just the working-class, but also capitalist development. That when workers struggle, capital responds, readapting how they manage workers to try and stop such struggles from happening again.

That’s the subtle part of it. Institutions become focused on optics—the way they present themselves externally—and how the workforce appears to react. So, they concentrate on fixing surface-level issues—the optics—while the real problems stay hidden underneath. The challenge is that by managing optics, institutions can obscure the actual conditions that drive discontent, making it harder for workers to recognize shared grievances or build momentum for collective action. This concealment means organizers must be more creative and persistent in exposing those hidden pressures and connecting individual frustrations to the larger systemic issues

Any final thoughts?

It might seem obvious, but it’s important to emphasize that a unionized workforce is a much safer workforce. The fairness of any workplace is closely tied to how well it is unionized. Our strike made this clear to everyone. For example, the catering division of Tate Enterprises wasn’t unionized. When we went on strike and protested, we were also standing up for them. But because they weren’t unionized, they faced even harsher consequences. The good news is that they are now in the process of unionizing—another important legacy of our struggle.

It’s also worth reiterating that within the institution, we represented one of the most diverse groups of workers. Tate’s decision to eliminate this part of its workforce was central to our fight. Institutions must be held accountable—both morally and practically—for how they treat their subsidiary and third-party workers.

Diversity was even more pronounced among third-party subcontractors in cleaning and security—almost all migrants—who typically faced fewer rights and more precarious conditions, especially during COVID (though at that time, they were not facing redundancy). Institutions cannot claim moral legitimacy while outsourcing systemic racism and injustice.

And, as we’ve mentioned, it’s important to underline how profoundly class played a role as well.

Class struggle is often dismissed as a relic of the last century—but nothing could be further from the truth. If anything, its effects are more brutal today, precisely because workers are so absent from politics and public discourse. This isn’t polemic—it’s fact. We still place hope in unions and grassroots movements, where the spirit of the left survives. But even globally, these forces are not yet strong enough.

What’s needed now is not just a shift, but a profound upheaval. As Luigi Pintor¹ pointed out over twenty years ago, humanity is increasingly divided: between those who live above institutions and those who live beneath them. These worlds are not just unequal—they are becoming irreconcilable in their experiences, perceptions, and ways of being. This is no longer about left and right—those labels have faded. It’s about drawing a new line. A moral line. One that separates those who live by domination from those who fight for dignity.

That is what we must resist—not only in protests and strikes, but in how we choose to live, every day.

We don’t need to win tomorrow. But we must act today—and every day—across borders, beyond boundaries. The goal is simple but urgent: to reinvent life in an era that is systematically robbing us of it.

author

Cristina Petrella

Subscribe to Notes from Below

Subscribe now to Notes from Below, and get our print issues sent to your front door three times a year. For every subscriber, we’re also able to print a load of free copies to hand out in workplaces, neighbourhoods, prisons and picket lines. Can you subscribe now and support us in spreading Marxist ideas in the workplace?

Read next

The Afters: Building a Hospitality Workers’ Movement in Glasgow

by

Nick Troy,

Odhran Gallagher

/

Aug. 21, 2024